Why you should ignore partisan pollsters | #210 - February 26, 2023

If correctly aggregating the public's opinions means slightly less accurate election forecasts some years, that's okay

Happy Sunday everyone,

It has been a relatively slow week in the world of political data, so I’m going to take this opportunity to write about something wonky that I have been thinking over for a while. (I am also giving a talk on a similar subject at the University of Maryland, College Park this week, and writing this helped me think through the slides).

I hope this post is informative to some people. Please share it if you think so.

I am admittedly a bit late to this, but I have a few comments to make on FiveThirtyEight’s recently published retrospective on their forecasts of the 2022 midterm elections.

I am writing this as someone who, like Nate Silver, makes a lot of election forecasts, so knows the struggle of communicating about polls in an environment where people are always misunderstanding you — but also as someone who wrote a book about public opinion polling and democracy and has different attitudes about which polls we should use, how we should use them, and what the whole purpose of forecasting is, anyway. I view reacting to Silver’s biannual forecasting post-mortem not as an opportunity to join the chorus of people complaining about his models — indeed, I believe much of that criticism has gone way too far, to the point where it borders on misleading — but to reflect on the challenges of polling in the year 2023 and comment on how popular methods need to be updated for the future.

Before we get into the nitty-gritty, though, I want to detail where I agree with Nate Silver. There are two big points:

First, the polls dramatically overperformed expectations last year, including doing much better than the errant popular perception that most surveys predicted a “red wave” — or even, according to some, a “red tsunami.” The average error in Senate polls, for example, was the lowest on record in a midterm year. Polls of the US House popular vote were also very good — even within a tenth-place decimal point, depending on how you aggregate and tally votes in uncontested seats.

To quote Silver:

Media proclamations of a “red wave” occurred largely despite polls that showed a close race for the U.S. Senate and a close generic congressional ballot. It was the pundits who made the red wave narrative, not the data.

Silver and I wholeheartedly agree.

Second, I also agree with Nate that allegations that sophisticated polling aggregates, such as those from FiveThirtyEight and The Economist, were being substantially biased by right-leaning pollsters “flooding the zone” are overstated. I think these theories are based on a misunderstanding of how complex aggregation algorithms work (and fair enough — they are very complex!): namely, in adjusting surveys from pollsters who have no track record or put out numbers that are systematically more favorable toward one party or another.

The best aggregators in the business significantly overperformed those from simpler poll averages. Take the averages from RealClearPolitics.com, for example, which before the election appeared to be committing two cardinal sins of data analysis: (1) manipulating its rules for which pollsters to include data from; and (2) adjusting surveys from all firms based on how biased the polls were on average in 2020 — both having the consequence of generating better numbers for Republican candidates.

It is clear that the broad philosophy FiveThirtyEight takes to political analysis is a good one. It is generally good to trust pollsters with track records of success more than those with no or negative track records; Models should be trained with robust methods and evaluated by their track record over many events, not just one cycle; And empirical analysis of polls still appears to dramatically outperform traditional punditry.

But despite the good performance of most pollsters and forecasters this year, the devil is in the details. There was a substantial influx of polls from right-leaning pollsters and outlets this year — and that influx was above and beyond what we have ever observed historically. It is the case that models should adapt to a changing landscape of measurements of public opinion.

In particular, through the research I have done for my book and election forecasts, I have arrived at a few differences with FiveThirtyEight about how we know whether a pollster is trustworthy, and how we should be making adjustments to polls that have records of bias towards one party. I think 538 is not comprehensive enough in evaluating the quality of a pollster; it is not harsh enough in punishing pollsters that obscure their methodology and engage in ideological thinking; and I think Silver ought to re-think how he grades pollsters based on their past accuracy.

It goes without saying, first, that none of this will be new to close readers of my work — and, second, that what Silver has done is still miles better than most of his competitors. But I think this is a good opportunity to clarify some of the challenges of polling and my vision for the future in one place. So here goes:

1. Why I don’t trust polls from Rasmussen Reports and the Trafalgar Group

(Lots of this is borrowed from chapter 5.)

I have a few criteria for establishing whether or not I should trust a political pollster. If they do any of the following things, I view their numbers as untrustworthy and worth a thorough review before deciding if I should include a poll in my models:

Generate fake data for any survey ever

Regularly ask extremely biased questions that prime respondents to answer in a certain way

Refuse to release methodological details about how the firm gathers and processes their interviews

Use a methodology that would generate substantially biased readings of public opinion (eg, using an unweighted internet convenience sample, or weighting data toward partisan benchmarks based on vibes)

Publicly share messages that are biased toward one party or ideology

Routinely release numbers that are biased toward one party or point of view above and beyond the range of statistically plausible results

If any pollster violates any one of these conditions, I put them on a list for further review. That review entails an analysis of all the polls the firm has ever released, a deeper study of their methodology — including how they get their data, how they process it, and whether results for demographics subsets look plausible — and, when pollsters are willing to cooperate, in-depth interviews with their methodologists and leadership. If this review fails to show the pollster is receptive to criticism and willing to update its methods, depending on the degree of infraction, I will not use their data. Even then, if a pollster meets any three of the red flags above, it’s wise to at least down-weight their data, if not ignore it completely.

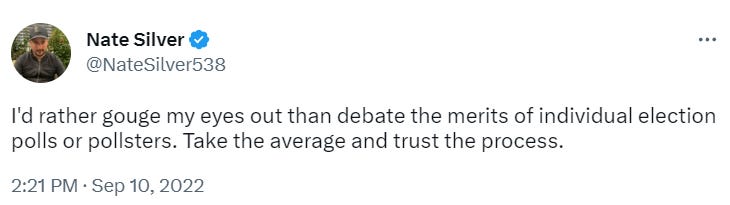

This is somewhat of an unorthodox view among polling analysts today, especially the loudest voices. Nate Silver’s philosophy, for example, is to use nearly all available polls and “trust the process” of his aggregation and adjustment algorithms to produce well-calibrated predictions of future elections. See his Tweet excerpted below when many analysts online were debating the merits of certain pollsters last election cycle:

In this framework, including surveys from Rasmussen Reports and the Trafalgar Group — the two most biased pollsters in America — is acceptable because the model is designed to adjust for any biases any given firm might be introducing to the process. In particular, Silver often mentions that the 538 model assesses whether a firm’s surveys are systematically more pro-Democratic or pro-Republican compared to other polls released during a given election cycle.

The within-cycle house effect is a good, but incomplete, method for removing suspected biases from an array of pollsters when you don’t know who is going to be more accurate at the end of the cycle. It is simple enough to see if a pollster releases surveys that overestimate Joe Biden’s approval rating by an average of 10 points compared to every other pollster. However, the adjustment breaks down in two big ways.

First, the house effect does not capture the possibility that some pollsters would produce more reliable data than others. It assumes that the data-generating process for each firm is equally as valid, comparing their data to the average of all pollsters in a race. But all polls are not created equal; Rasmussen and Trafalgar, for instance, engage in shady survey methods and justify them because they produce numbers that agree with their ideological priors. A model that is trained to remove empirical biases from surveys still confers validity onto those pollsters. This is a problem with the theory of the house effect. You should not be any more likely to believe the result of a single poll based on the argument that a model can remove bias from it.

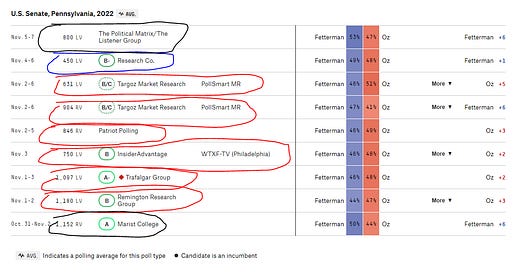

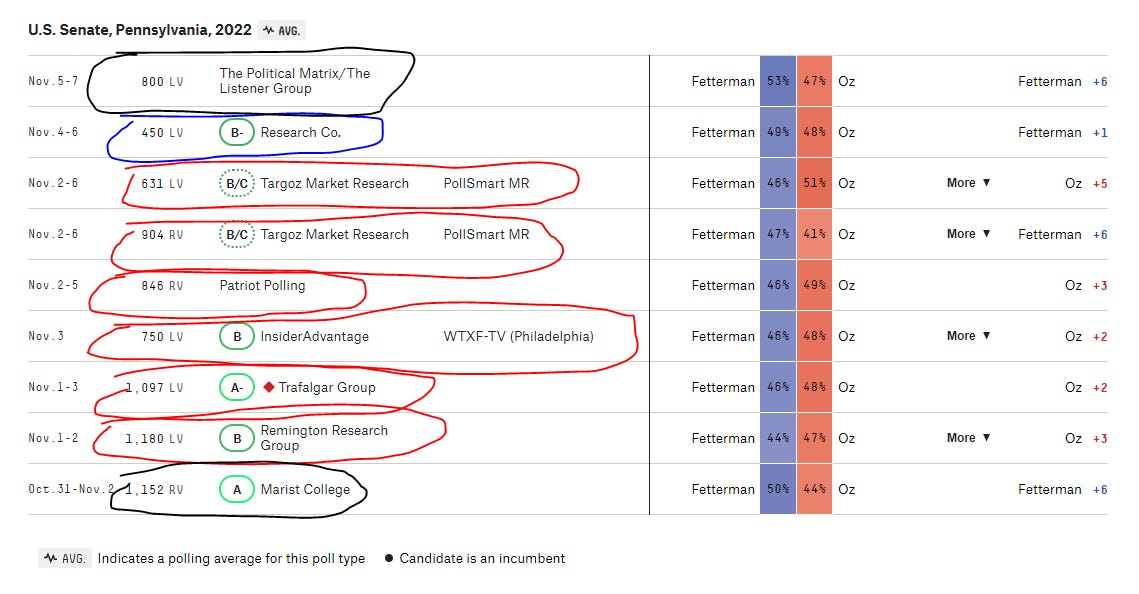

Yet perhaps the bigger problem is that the house effect adjustment only works in a given race if there is a healthy supply of (high-quality) surveys there. Running a model to measure whether a pollster is more biased than the average does not work when the vast majority of polls for a given race are from biased outlets. See, eg, Pennsylvania’s 2022 Senate race, pictured below. Here it is possible that Marist College, which was off the eventual result in PA by just one percentage point, would have been dinged for being an outlier compared to the other GOP-titled outlets.

These problems usually drive advocates of a “take all the polls and trust the process” approach to turn to empirical analysis. Silver says that including Rasmussen and Trafalgar is the “right” move because it lowered FiveThirtyEight’s error relative to other specifications in 2020 and 2016. But, setting aside the issue of whether we want a forecast to be right because it just so happened to get a supply of junk from two rogue pollsters, the firms were both demonstrably biased in 2022. Silver says in his model review that “some of the polling firms that were least accurate in 2022 were actually the most accurate in 2020. … pollsters such as Trafalgar and Rasmussen will take a hit, which will give them less influence in the polling averages in 2024.”

That’s because the outlets were putting their thumb on the scale for Republicans. But this was not a surprise! The Trafalgar Group had the highest level of empirical bias relative to the average of all other polls in both 2016 and 2020.

Including surveys from these firms “helps” predictive accuracy in a year like 2020, when the methods used to measure public opinion break down in ways that favor one party among almost all polls following standard methodological practices. But in 2022, when the tools used by the average pollster worked, treating polls from the trouble pollsters — including not just Rasmussen and Trafalgar, but other GOP-leaning pollsters too —hurts overall accuracy.

FiveThirtyEight could directly address this criticism by showing us two versions of their models — one that includes trouble surveys and one that doesn’t — but they don’t do that. That seems like an easy thing to remedy.

At any rate, I do not buy either of the arguments that (1) there is an empirical case for using extremely biased polls, based on the forecasts that subsequent models generate; or (2) that there is enough historical data, and aggregation algorithms are sophisticated enough, that we should prefer empirical adjustments for suspected bias over a comprehensive reading of a pollster’s record and their current data-generating process. It is possible to “trust the process” of polling aggregation for trusted outlets while acknowledging that some pollsters have profound problems that should warrant their data’s removal from mainstream models.

2. If we must use polls from biased firms, what’s the best way to do it?

But let’s assume you’re not convinced of my position. After all, FiveThirtyEight’s models are very well calibrated; maybe Silver could squeeze out a few more decimals of probabilistic accuracy while satisfying the condition for stricter standards, but maybe it’s just not worth the effort.

Plus, you might say, FiveThirtyEight is not blind to these modeling challenges. The site issues a comprehensive rating scheme for pollsters based on their historical accuracy that purports to solve the issue of unequal data-generating processes and biased groups of polls. Per Silver’s method, polls that have a record of lower absolute error in predicting past elections get a boost in the house effect and averaging algorithms.

Again, this is a good start, but it runs into three larger problems.

First, there is a problem of small sample sizes and correlated polling errors within election years. The logic of the rating system is that firms get boosted or bumped only if they perform well across a high supply of individual polls. But when polling error is highly correlated across races within years — partisan nonresponse was not high just in Texas in 2020, for example, but all throughout the country — it is much easier for a pollster to get lucky with their methods by gaming the system in one or two years.

This problem is made much worse when ideological thinking, for example, rather than methodological choices, pushes firms to generate polls that are lucky outliers. The Trafalgar Group in 2020 ends up getting rated better than the industry average because they polled a lot of races and their ideological bias — rather than methodological savvy — pushed them to include more Republicans in their polls. This is contrary to what would happen in the previous era; Then, polls were off if a firm chose a new method for interviewing or weighting, etc. That would presumably translate to good performance in the future. Dumb luck from ideological bias, however, does not.

This would not be so large an issue if Silver used an alternative measure of a pollster’s worth. That is the second problem with the historical ratings system. Silver focuses on a pollster’s absolute accuracy when looking at their bias relative to the bias of the whole polling industry can tell you more about what motivates them. Focusing on accuracy instead of bias is what leads the system to give the famously opaque and partisan Trafalgar Group a higher rating than the many other credible pollsters in Silver’s dataset, for example. But it also has one of the highest levels of bias; When the polling industry at large suffered from high levels of partisan non-response bias in 2016 and 2020, the pollsters that massaged their data to make polls more favorable for Republicans got better ratings in 538’s rankings.

The 2022 midterms show how accuracy-based scores break down. In essence, giving pollsters a premium for accuracy can end up rewarding firms when they use suspect practices to avoid problems of polling that nearly uniformly affect all other firms following standard practices. But that is different from a firm being “better” than the others.

Third, there is the issue that up-weighting accurate polls betrays the statistical theory of aggregation. Statistically, averages of data do not become less biased when they hue closer to more empirically accurate groups, but less biased ones. I explain more in these links (link 1, link 2) but the upshot is that a pollster that releases several polls that are favorable both to Democrats and Republicans has a better tool to measure public opinion on average than a pollster who releases surveys that are always a little biased toward one side.

To be sure, I am not the only one to make this methodological case. In Nate Cohn’s average of 2020 presidential election polls for the New York Times, he writes similarly:

A poll average needs unbiased polls a lot more than it needs accurate polls.

Imagine two pollsters. One conducts three polls and shows Hillary Clinton doing exactly three percentage points better than the final result each time. That’s an average error of three points. Another poll also does three surveys, with one showing her doing five points better than the final result, one showing her doing two points better and one showing her opponent doing five points better than the result. That’s an average error of four points. But a poll average consisting only of the more accurate pollster would oddly fare much worse. It would show Mrs. Clinton leading by three, while the poll average consisting of the less accurate poll would show a dead heat.

This is why polling averages should give a premium to pollsters that have been less biased, not more accurate over their lifetime of releasing election forecasts. And the empirical evidence for this approach is solid; my final polling averages for the 2022 midterms were less biased than FiveThirtyEight’s in every state.

Looking at both FiveThirtyEight’s house effects algorithm and the model that generates its historical ratings, it’s clear that Silver is overstating his model’s ability to avoid problems when pollsters “flood the zone” or put out numbers from methodologies that are motivated by ideology instead of empirics.

3. Why do we make election forecasts, anyway?

To reiterate, I am not writing this post to start a pissing contest with any forecaster in particular. Silver’s models are much better than, say, the RealClearPolitics estimates or whatever you’ll find on Fox News. But his post-mortem ignores some of the more valid criticisms of his models. That is, in part, a shame, because they could be addressed simply. But it also presents an opportunity to iterate on past methods to deal with new problems facing political polling.

Still, I keep coming back to this claim that including polling from biased sources is good when it makes predictions more accurate. I find this troubling, I think, because I do not view prediction as the end-all-be-all measure of the success of a model. Accuracy is not so important as to override a model’s statistical and philosophical integrity. There is such a thing as being “right for the wrong reasons.”

Maybe the question a forecaster needs to ask themself is:

Do you want your election forecasts to be “right” on average because you hedged your analysis of good polls with junk produced by x, y, and z polling firm, or because you gave people a proper distillation of public opinion polls in a given year, warts and all?

Is it enough, in other words, to be right for the wrong reasons — say, pulling a probability back toward 50% without an empirical reason — in two election years even if that makes your forecasting record worse in the future? I acknowledge that, with the population of elections being what it is (very low-n!), this is a hard question to answer empirically.

But a related question for everyone who consumes polls and election forecasts is whether it really ought to be the job of the most famous political data analyst in America (indeed, maybe the world) to give people predictions of elections that ignore major changes in how people are answering polls and how pollsters are conducting surveys — or whether we collectively want an analysis of public opinion that is balanced both towards predictive accuracy and correctly measuring and understanding the general will.

If we decide that the latter is our priority, then integrating these new philosophical and methodological approaches is a good place to start.

Comments are welcome below and by email.

Talk to you all next week,

Elliott

Monthly mailbag/Q&A!

I am collecting Qs for the March Q&A! If readers submit enough, it will come out next Tuesday. Go to this form to send in a question or comment. You can read past editions here.

Subscribe!

Were you forwarded this by a friend? You can put yourself on the list for future newsletters by entering your email below. Readers who want to support the blog or receive more frequent posts can sign up for a paid subscription here.

Feedback

That’s it for this week. Thanks very much for reading. If you have any feedback, you can reach me at gelliottmorris@substack.com, or just respond directly to this email if you’re reading it in your inbox.

thank you, well done and a very nice summary of issues laypeople (like me) encounter in casual conversations around election time

This guy is a straight Retard. He has his opinions so far off based and incorrect. 1st: 538 was wildly inaccurate for both 2016 and 2020. They shortchanged Trump 2.8% in 2016 and 4% in 2020. 2nd: AtlasIntel and Rasmussen were by far and away the most accurate pollsters of 2016 and 2020. What you're doing is akin to saying 5+5=732, but 5+5=10 is definitely the most incorrect answer. You don't deserve a job in this field. I guess they just let anyone with a pulse write articles these days.