The "worst polls in decades" call key assumptions of surveying, and forecasting, into question

The politicization of public opinion surveys has hurt their ability to reach a representative portrait of Americans. But surveys are still useful, despite critics' claims.

The American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) just released its quadrennial analysis of what went wrong in the polls during last election. “The 2020 polls featured polling error of an unusual magnitude,” the commission responsible for the report wrote:

It was the highest [error] in 40 years for the national popular vote and the highest in at least 20 years for state-level estimates of the vote in presidential, senatorial, and gubernatorial contests. Among polls conducted in the final two weeks, the average error on the margin in either direction was 4.5 points for national popular vote polls and 5.1 points for state-level presidential polls.

That is indeed the worst misfire in generations. The last time polls were that astray was in 1980. That year, the average absolute error was about 6 points on the Democratic candidate’s vote margin.

But one problem with the way AAPOR reported topline polling error is that survey data can still be accurate and have a high absolute error. If three polls in 2020 gave Biden a margin of 8, 0, and 6 points, for example, then their average absolute error is 10 points. But their average bias, ie raw error, would have been a 1 point over-estimation of Biden. When it comes to aggregating data and making predictions, we care much more about minimizing bias than we care about minimizing variance. In other words, if one problem is that polls can be accurate with a high absolute error, they can also be biased with a relatively medium-sized error (such as last year’s).

The big problem in 2020 was not that polls were inaccurate, but that the polls were relatively uniformly biased. As the AAPOR says:

The polling error was much more likely to favor Biden over Trump. Among polls conducted in the last two weeks before the election, the average signed error on the vote margin was too favorable for Biden by 3.9 percentage points in the national polls and by 4.3 percentage points in statewide presidential polls.

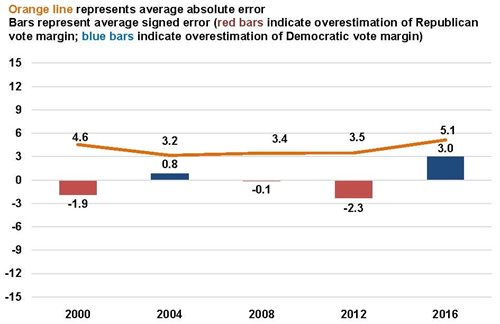

By way of comparison, here are two graphs AAPOR drew up for their 2016 report. They show the average absolute error (line) and bias (bars) for national polls in each year going back to 1936. A 3.9-point pro-Democratic bias is the largest since 1980.

And here is the same figure, but for the state polls. A 4.3-point pro-Democratic bias is the worst they have ever measured, and about 40% worse than the bias towards Clinton in 2016:

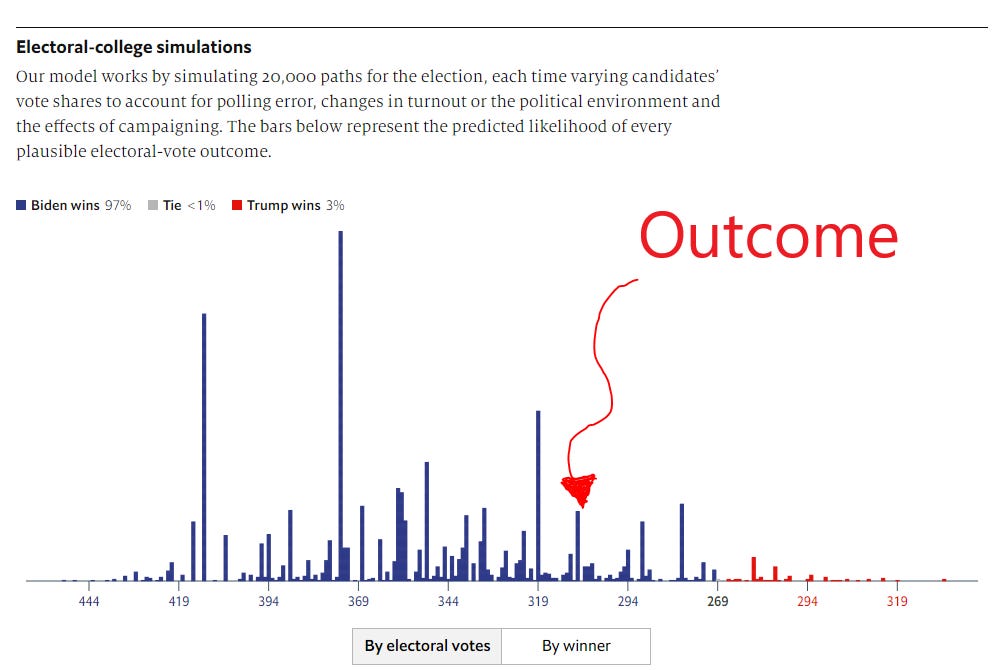

This 4.3-point bias towards Biden explains why our polling averages and election forecasting models looked so wrong in hindsight. A model of inaccurate polling data — data which is spread around some average — can still be relatively unbiased, such as in 2008. The polls in 2020 were bad because they were inaccurate and biased. If you simulated the average state-level polling bias based only on the graph above, you would end up with a 4.3-point average bias in way less than 10% of scenarios. (Most election forecasters usually simulate bias using the distribution of accuracy, which leaves a more reasonable 13% chance of a 4.3-point error.)

But here’s the big problem: a higher probability of uniform errors across pollsters and geographies actually breaks one of the chief assumptions of polling aggregation: that polls are off due mainly to individual random noise that cancels out across surveys. If a lot of different surveys across the country are being moved around by the same source of error, you can’t rely on aggregation to cancel it out. Averaging biased noise together only gives you a stronger, but still biased, signal. This means that the main way the news media ingests polls isn’t as reliable as it used to be; errors are bigger and less predictable now than they were in, say, 2008. And that will take adjusting to.

One potential source of hope is that forecasters can use a sophisticated aggregation model to directly incorporate the time-dependent probability of correlation in the underlying data generating process. Polls in 2016 and 2018 were off by larger amounts in states with more Trump voters — and that should have told us something about the chance for error in 2020. This might mean that we create models that appear to under-fit polling data and election results — in other words, to generate predictions that look too spread out — but that perform better on data in recent elections. We tried one version of this last year, but have even better ideas for our next go at things.

A problem with polling

So why, exactly, were the polls almost all off in the same direction? Why was the bias so high? Although the AAPOR report does a good job dispelling some myths about why polls were off — there are no “shy Trump voters” lying to pollsters, they say, and this wasn’t a redo of the education weighting problems of 2016 — the authors are short on real answers. The leading hypothesis among the pollsters and political statisticians I talk to is that Trump supporters were simply much more likely than Biden voters to refuse to answer pollsters’ calls or take their surveys online. That decreased their representation in the polls.

In the polling world, we call this “differential partisan non-response.” The AAPOR researchers put this possibility forward, too, though they miss some key accounts that really prove the point.

First, take some of their data as an example. The report’s authors used the microdata behind an unnamed national poll conducted using random-digit-dialling and adjusted it so it had the correct share of Biden and Trump voters. They found there wasn’t any significant change in the share of people by age, race, education, or income — but that there were too many Democrats and too few Republicans. Democrats as a whole were overrepresented by 3.5 percentage points, and Republicans underestimated by 4.

Looking across polls, the AAPOR report finds polls that did not enforce bounds on the share of Democrats and Republicans did worse than those that did:

This is enough evidence to suggest the presence of non-response bias, and it is where AAPOR stops. But it is not the whole story.

Doug Rivers, who designs the methodology behind the polling at YouGov, told me in a conversation after the election that the 2016 Trump voters who were still active in YouGov’s site in 2020 and disapproved of the president’s job performance were much more likely to fill out surveys last year than the ones who approved of him. That means that weighting his polls to match the results of the 2016 election didn’t help correct for all of the bias when estimating the results of the 2020 contest, since the group of past Trump voters that turned up in surveys were less likely to vote for him compared to the group of Trump voters in the real electorate

This bias within the partisan groups helps explain why other polls that adjusted for party ID or 2016 vote were still biased towards Biden (though less biased than other modes, such as unconstrained RDD estimates). It’s also a reminder that the real “fix” to polling will not come via a search for more accurate statistical methods or fancier panel designs, but by proper balancing of the samples that go into the poll. There is no way to weight your way out of bad data.

I will add, for posterity’s sake, that it also makes sense that we would see partisan non-response in the polls these days. Donald Trump repeatedly during his 2016 and 2020 campaigns told his supporters that polls were “fake” and designed to “suppress” them. It is not surprising that they would hear those messages and subsequently decline to answer the polls. Do you take part in activities you view as corrupt, or to your detriment? That is not to justify the objection, but it could help us understand it.

And a problem with poll-watching

Let’s take stock of the situation. We have learned two lessons so far: First, that polls in 2020 were systematically off because Trump supporters, regardless of their demography or geography, refused to take surveys at higher rates than Biden’s voters; and second, that this changes the landscape of potential polling error in ways that partially invalidates the assumptions underpinning polling aggregation and makes forecasting less reliable — especially when it comes to estimating potential uniform bias across surveys.

There are two more things I’d like to note. First, the authors of the AAPOR report make a set of remarks on expectations of precision that are similar to the things I’ve written before and are worth quoting at length:

Polls are often misinterpreted as precise predictions. It is important in pre-election polling to emphasize the uncertainty by contextualizing poll results relative to their precision. Considering that the average margin of error among the state-level presidential polls in 2020 was 3.9 points, that means candidate margins smaller than 7.8 points would be difficult to statistically distinguish from zero using conventional levels of statistical significance. Furthermore, accounting for uncertainty of statistical adjustments and other factors, the total survey error would be even larger.

The temptation to interpret polls as precise predictions arose in part because polls did so well predicting outcomes in 2008 and 2012. Nonetheless, putting poll results in their proper context is essential; whether or not the margins are large enough to distinguish between different outcomes, they should be reported along with the poll results. Most pre-election polls lack the precision necessary to predict the outcome of semi-close contests. Despite the desire to use polls to determine results in a close race, the precision of polls is often far less than the precision that is assumed by poll consumers. The polls themselves could exacerbate problems of scientific legitimacy when they are unable to live up to unrealistic expectations.

This might be the biggest lesson we can learn from 2020. It is clear that the polls have big problems that need to be sorted. But the real failure last year, in my mind, was an overconfident press and public that underestimated the range of polling error and was too sensitive to a 1.5-standard-deviation miss. But here, the AAPOR report falls short again. They put too much blame on the consumer and not enough on the producer.

At the very least, political journalists also bear some of the blame for not understanding how pre-election polls could be so wrong. It is their job to understand the data-generating process behind the numbers they report. Perhaps if they did a better job evaluating their own assumptions about that, they would not have reacted so incorrectly in the aftermath of the 2020 election.

However, pollsters and election forecasters bear a lot of the blame for the press’s and public’s overconfidence, too! Pollsters are in the wrong for not conveying the true magnitude of potential error in their data. Most pollsters report the margin of sampling error in their data — a number that conveys how off their data could be because of random differences between who they are trying to talk to and who they get. But there are at least three other types of error we know about! Polls can also be off because the universe of everyone you can reach over the phone or the internet is systematically different in unmeasurable ways from the full electorate; because of the chance that refusals are correlated among groups (as the 2020 error demonstrates) in ways we can’t adjust for; and because the questions they ask don’t fully capture the way people feel or behave. Every adjustment you make to a poll to bring it in line with the true characteristics of a population — demographic, political, or otherwise — also further increases the margin of error, due to the chance your weighting scheme is wrong or overfit.

There is not just sampling error, in other words, but also coverage error, non-response error, and measurement error! Studies of pre-election surveys (and the election results themselves) have shown the full margin of error of election polls to be at least twice as large, historically, as the one pollsters usually report. And that’s historical deviation; it could be even larger now since non-response is correlated with partisanship in new ways.

And election forecasters don’t always help. While it’s true that the prediction models in 2016 indicated the election was closer than most people appeared to realize, and the 2020 models said Joe Biden’s margin in polls could withstand even a large polling error in Trump’s direction (which is what happened), the probabilities we present could confuse people, and the bragging about polling’s success in 2008 and 2012 could have set the wrong expectations. One thing I learned from 2020 is to be humble in our forecasting, and not to assume past patterns of error will fully capture future deviations even if that is the statistically sound decision to make.

Polls still work — for election forecasting, and as a reflection of the general will

Finally, I fear is that all this hand-wringing about pre-election polling has made us forget their value to democracy.

In THE WEEK magazine yesterday, an associate professor at George Washington University names Samuel Goldman wrote an article titled “The polls don’t work — and that’s a good thing.” He is wrong on both accounts!

In fact, the piece makes several factual errors that could have been caught by even the lightest editing. It makes other glaring omissions that anyone with a deeper than surface-level knowledge of polling would have thought of. For example, Goldman writes “Immediately after the election, some pollsters speculated that "shy Trump voters" who falsely reported supporting Biden might have skewed their results. The report finds little evidence for this hypothesis.” That may be true if you cherry-pick articles, but even the early comprehensive accounts from the pollsters didn’t take this seriously. The industry has poured cold water on the “shy Trumper” theory since early 2017. It’s simply not the case.

Goldman also writes that “Whatever the cause, polling doesn't work when refusal to participate in polls is strongly correlated with candidate or party preference. You can't find out what the people think when half of them won't share their opinions.” This is half right, but again, he must not have read the report. The problem is not that half of the voters won’t answer the phone, but that Republicans are just disproportionately less likely — maybe 10% or so — to do so.

And, on a more fundamental disagreement, polling is not broken, it is not “not working” — the problem is one on the margins, not one of failure. The only definition under which polling is “not working” is if you are expecting it to tell you, within a point or two, how everyone will vote. Polls were never designed to provide that level of accuracy — if Dr Golman had read the report closer, he might have understood that. =

He also writes that the polling failures in 2016 and 2020:

help dispel the illusion that politics is a predictive science best practiced by highly-trained technicians. Quantitative data have a role in predicting electoral outcomes. But they don't replace historical understanding, local knowledge, and sheer intuition. Candidates and advisors who have these virtues are more important than sophisticated statistical instruments. As the saying goes, there's only one poll that matters: the one on election day.

I would disagree. Slanted campaign journalism and elite “intuition” in 2016 was a reason why many east-coast reporters and Washington insiders took Hillary Clinton’s position in the polls for granted. The 1/3rd odds FiveThirtyEight’s model assigned to Trump’s victory then was certainly higher than the impression I got reading the news at the time. But, more to the point, polls are the only regular, objective reading we have of how the voters — at least those who will pick up the phone — say they will act. There is no other tool that can do this, and there is a reason we all keep coming back to the polls for our horse-race fix: on average, and most of the time, they are as good as you can get. The 2020 polling error was, after all, just a 2 percentage point overestimation of Joe Biden’s two-party vote share. Considering all the complexities of human behaviour, that is pretty admirable already.

But let’s not forget the heinousness of the latter half of the headline — that it would be a “good thing” if the polls were broken. Really? Over the last 80 years, the politics industry has reoriented itself around our readings of what people want. Without the polls, how could we tell what their agenda is? Elections won’t generally tell you that — and if you get rid of the polls, you can forget about taking the will of the people into account between election cycles. Without the polls, America, with its minoritarian electoral institutions, would really have no way of ascertaining the general will of the majority of citizens.

And besides, the question is not what a world without polls would look like, but what would come to replace them. Perhaps it would be Washington insiders and elites like Professor Goldman. I posit that would leave us much, much worse off.

Down, but not out

Pollsters, in summary, are in a pretty rough spot. They are having the hardest time in recent memory reaching the people they purport to represent. A good chunk of Republicans, for their part, couldn’t care less — so long as their leader is beating expectations and making a fool out of the behavioralists and their calculating machines, they are content. This will decrease the weight put on their opinions by interest groups, activists, the press, and politicians.

The AAPOR report also raises some excellent points about our misguided expectations for the polls. We have come to rely on them too much, and precisely at a time when the assumptions underpinning them are being thrown into question. And if partisan non-response continues to affect surveys nationwide, the aggregation process will not be as reliable at cancelling out biases as it was before.

What can you do to help? So long as polls are part of our democracy, the best thing we, the people, can do is to give pollsters a chance when they falter and cheer them on when they try new things to fix their mistakes. And you could also answer the phone the next time they call.

Let me timidly and semi-facetiously suggest another explanation: the polls were right, the actual results were skewed by massive fraud with Trump supporters literally voting early and often.

Elliott, would you say that it's necessary to create another variable for GOP voters that weights for their nonparticipation in polls?