The gory details about how modern polling really works | #207 - October 23, 2022

Kitchen Confidential, but make it about polls

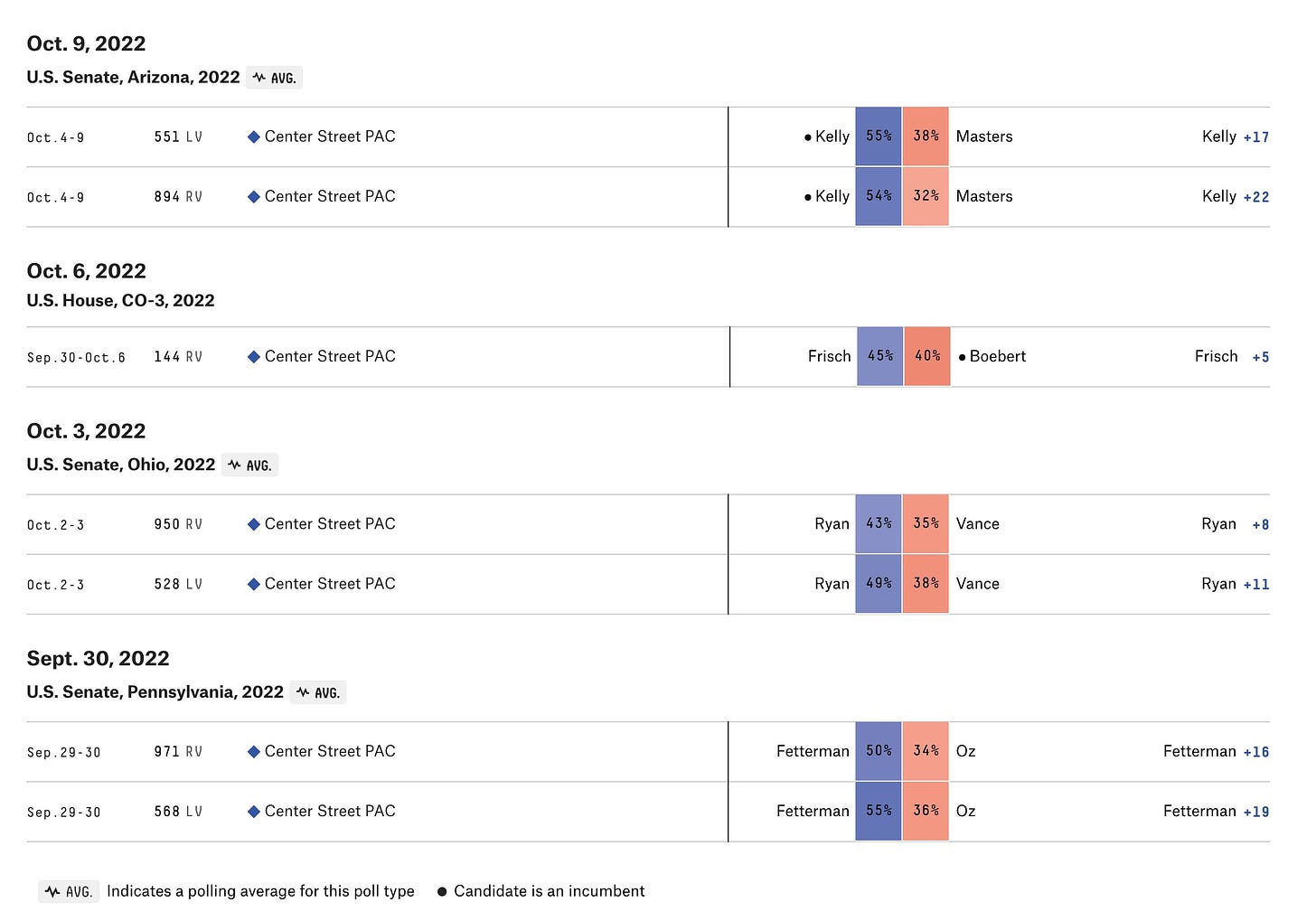

This week, I reported a story for The Economist that uncovered some very troubling details about pre-election polls being published by Center Street PAC, a new and self-described “non-partisan” super PAC that has pledged support for Democrats in key Senate contests. Center Street PAC has published some truly outlandish results over the course of this election cycle. What explains their systematic and severe pro-Democratic bias? Are the results justified? Is something more nefarious going on?

The story is here. Please read it. For more, here is a Twitter thread about what we found and how we found it:

The upshot to this narrow story about Center Street is that they have made some questionable methodological decisions that conveniently push almost all of their numbers in the Democratic direction. One explanation is that they do not know any better; Their pollster is the head of an investment firm and has never done this type of work before. Another runs deeper. The group gets their polling data from an opaque online survey operation that inherently does not produce representative surveys (you cannot randomly sample people on the internet), meaning researchers must do a lot of weighting and modeling to bring the polls in line with key demographic and political benchmarks for the electorate. Whend one properly, that increases uncertainty. When done poorly, it produces bad polls.

Frankly, this is a really bleak picture, and I no longer trust the results of the polls from the PAC. But the bigger issue is really about what the data tell us about the state of polling today. Center Street PAC shared their data from 8 polls of Ohio with me, and using four different weighting schemes I was able to change the percent of voters who support JD Vance in the state’s Senate race by 17 percentage points. This should not happen. It is a sign of severe shortcomings in the way the sample was produced. Maybe because response rates are low, but it’s more likely the problem is due to representativeness of the entire panel, not just the sample.

That gets into what I really wanted to say about this story but didn’t have the space to. And that is that This dynamic where a methodologist collects a bad sample and has to select the perfect combination of weighting variables and question-wording in order to produce a reasonable poll is (A) not exclusive to super PACs that are in the tank for certain candidates and (B) a violation of the traditional assumptions underpinning survey research, meaning uncertainty is a lot higher than we are led to believe.

To show you what I mean, let’s walk through an example hypothetical online poll to show you just how many steps it takes to go from interviewing 1,000 Americans about politics to a topline 51D - 49 R result on the generic congressional ballot — and how many things can go wrong along the way:

Step one: contact an online survey firm to buy access to 1,000 American adults randomly sampled from their panel.

Send these 1,000 people an email with a link to an online survey, that you create. You get to choose the words for the questions and answers — formulating both how people are asked topical questions and giving them the vocabulary with which they express their actual attitudes. Let’s say there are 20 questions about a person’s demographics, past voting behavior and current vote intention for the race in their home congressional district. After sampling, The survey firm sends you an excel file with 1,000 rows and 20 columns, representing the answers to each question for each participant. Now it is your job to turn that spreadsheet into a poll result that people can read.

Your first need to see if the sample’s demographic characteristics match benchmarks from the US Census Bureau. Let’s just say the numbers should be 65% white, 15% Black, 13% Hispanic, 4% Asian American/Pacific Islander and 3% other. But the numbers you get are 80% white, 10% black, 5% Hispanic and 5% for AAPI/other. You have to use statistics to give those underrepresented groups more weight when calculating, for example, average support for Joe Biden. And you repeat this process for education, age, and sex—making sure that all benchmarks are met simultaneously.

This turns out a sample where 60% of people say they voted for Joe Biden in 2020 and 40% say they voted for Trump (for now, let’s ignore nonvoters or supporters of third-party candidates to simplify the example). This is obviously wrong, so you adjust for it, too.

That makes your sample politically representative overall, but you really have no clue how to make sure the particular subgroups are calibrated correctly. It is totally possible that the white voters you talk to, for example, support Biden too much, and the non-whites are too Republican-leaning. There is nothing you can do about this; you do not have a voter file and do not want to make guesses about benchmarks for these subgroups.

But you could split some groups into smaller subsets. Maybe you weight not by race and education separately, but together—making sure that there is, say, a 35% share for non-college-educated white voters in your survey and 5% college-educated African Americans. This might help a little, but now you have exposed your survey to higher variance; if these smaller groups are weird, you’ll get even weirder results when everything is aggregated together!! Your margin of error is consequentially very, very high.

In exchange for that variance, maybe you cut down on another variable. Maybe you just say, by fiat, that age or sex isn’t very important. So be it: you want a simple survey, and we won’t know the results of the election until November anyway. So you move on.

Now that you have a weight for every person in your poll, you can start calculating support for Democrats and Republicans nationwide. But now you have to actually process the responses to your question! And you notice that you forgot to do something when you programmed the survey: you forgot to ask people who said they were unsure which party they liked to pick someone if they had to. Consequentially, you end up with 15% of your sample being a group of undecided voters that are about 80% Trump voters and 20% Biden voters. The rest of the poll is 35% for the Republicans and 40% for the Democrats.

You are faced with a big question here. Do you assign these undecideds based on their past voting behavior? That could work, but some may have changed their minds. You decide a good thing to do is check what the poll would say in either scenario; if the results are similar then it doesn’t really matter. But you are wrong, there is a huge difference! If you do not push undecideds into their partisan category, your poll result is D+5. But if you do, then the result becomes R+5! (The math on that is [(+5*0.85) + (-60*0.15)]) So which version to you report? Are you just honest to people about the process? No, you pick the D+5 because it’s the version that makes the fewest assumptions.

Final answer: D+5.

So, that’s what statisticians call your “data-generating process” (DGP) — the steps you take to gather and process your data. Notice how many things in it could change the results of your poll? What if the electorate is 62% white instead of 65%? What if undecideds really do break toward Republicans? What if your sample is undercounting Biden young white Biden voters, or older, conservative Hispanics? The answer is: you don’t really know! But you do know that all of these factors could push the result of a revised poll away from the result of your first one.

That is, in a way, what happened to Center Street PAC over the past few months. And it’s also what could happen with every single poll. Sure, the average good pollster might have more representative samples and makes sure to ask undecideds which way they are leaning. But they don’t all do this: and there are a lot of pollsters working with data that is, frankly, crap. And as this exercise shows: you cannot weight your way out of bad data.

This also means that polls have more uncertainty than you are usually told. The traditional “margin of error” that a pollster publishes captures only the error from one of the steps we detailed above! We know that is incomplete: Error does not come only from random variation in who is sampled for a poll, but also, from how the list of potential respondents is assembled and whether it is itself representative (eg, some groups do not have internet access, or landlines telephones); from who responds to that poll (they may be more Democratic or Republican on average, even within demographic groupings); from how those respondents are weighted (choose the wrong traits and you won’t be able to adjust for all the nonresponse in the survey); whether the question measures the attitude or trait it is intended to measure (like whether you are counting “soft” preferences from voters as them being completely undecided); and on and on.

When all of these sources of error are taken into account the “true” margin of error of a poll could be at least twice as large — or maybe even higher — than the margin of sampling error that pollster publish. And this is a key distinction: it means that any given survey is subject to much more noise than is commonly assumed.

Does that mean we throw out the polls altogether? No, of course not. They are the best tool we have for predicting election results, and more important than that, they are also fundamentally necessary for the functioning of a modern democractic society.

But polls are not perfect. They never have been, and never will be. As the problems with Center Street PAC shows, that is more apparent now than ever.

Subscribe!

Posts for subscribers

Consider a paid subscription to read additional posts on politics, public opinion, polling and election statistics, and democracy. Subscribers got one post last week: a thread on potential polling bias and a better way to visualize error.

Monthly mailbag/Q&A!

The next blog Q&A will go out on the first Tuesday of November. For those keeping track, that is election day in America. If you want to send in a question or public comment for me to respond to before the polls close, go to this form. You can read past editions here.

Feedback

That’s it for this week. Thanks very much for reading. If you have any feedback, you can reach me at this address (or just respond directly to this email if you’re reading it in your inbox).