Q&A #2: Multiparty democracy, candidate quality in Senate elections, and Constitutional amendments

With additional posts on the Supreme Court and Australian elections

Welcome to the blog’s monthly(-ish) Q&A. Remember that you can submit questions for future issues here. I read every question and 98% of them eventually get answered!

This week’s questions mostly revolve around handicapping for the upcoming midterms and how to reform the institutions of American democracy—particularly the Supreme Court, federal voting rules, and (interestingly) the Constitutional amendment process.

If you enjoy this post, please share it!

Mark asks: “While the smart money is on Republicans winning the House & Senate midterms pretty handily, what do you think the chance is that Republicans underperform relative to what the fundamentals might suggest due to candidate quality (thinking particularly of Mastriano in PA, Lake in AZ)? Is that answerable by comparing fundamentals-only vs fundamentals+polls models?”

This is a good question and one I answered briefly in Saturday’s subscribers-only thread. The answer is that candidates routinely underperform expectations because of their idiosyncrasies, scandals, or deficits in quality. In fact, in forecasting models for the House and Senate, it is a common practice to include a binary variable that indicates whether a person has held office before or is otherwise not qualified to run. This can be somewhat subjective, but it is an important thing to account for, empirically speaking.

As for the specific examples, I am not sure that Doug Mastriano fits the bill of a traditionally “low-quality” candidate. Sure, he is dangerous and more than a bit loony, but he has held office before, has the support of his party, and seems to be fundraising enough. The polls for the race are pretty tight. To be sure, those polls do have him down 4 points versus his opponent, which is not what we would expect in a state that leans about 3 points on margin to the right of the nation when the national environment is around R+2 today, according to generic ballot polls. So he does seem to be underperforming.

Kari Lake, on the other hand, is your classic “low quality” candidate. She is ideologically fringe, has not held office before and despite strong fundraising is underperforming the fundamentals of the R+4 state; recent polling has her down by about 3 points on average. But the gubernatorial primary there is not for another month and things will change before them.

The other place to keep your eye on this is Georgia, where Herschel Walker also gets punished for being a low-quality nominee. Polls there also suggest he is lagging behind expectations based on the national environment — one survey out last week had him down 10 points (though I have my doubts about the validity of that number).

The upshot of all of this is that a partisan imbalance of candidate quality — one party having the lion’s share of low-quality candidates — tends to boost the other party’s aggregate national odds of holding power. And that looks like exactly what’s happening in election forecasts and betting markets right now.

Claudia asks: “What are the pros and cons of increasing the number of Justices on the Supreme Court? And, how smart or practical would it be to do it now (in this day and age)?”

I am not a scholar of the Court, but I can think of a couple of points in both categories:

Pro: Increase the number of justices nominated by the numerical majority (if you do it before November 2022).

Pro: Include more viewpoints in important judicial decisions. To take a potential point from the literature on legislative institutions: There is generally a link between the size of voting chambers and the chance of having successful third parties. More judges may mean more representation off-axis of the left-right spectrum.

Con: Expansion risks making the Court seem more political than it already is. (On the other hand, it is decidedly political, and politicizing it further likely produces more good if you’re increasing representation for the majority, too.

Con: Expansion increases the long-run probability of Republicans nominating conservative justices, who are currently engaged in a long-term battle against political rights and regulatory rollbacks, which I think is bad, and who I generally don’t like because I don't believe in originalism

A few other considerations. First, why should we be stuck with 9 anyway? That number doesn’t appear anywhere in the Constitution. There is nothing magic about the number nine. If you wanted a magical number you might be better off with a prime number. Perhaps 11 or 13. Or, if we’re getting crazy, 17.

Second, you could always let the size of the court vary. Some law professors have suggested letting every president nominate one or two new justices at the beginning of their term and letting that be that; not filling seats that go vacant because of deaths or retirement, not passing new laws to expand its size, etc. That would also ensure the de-facto partisanship of the Court matches the medium-term partisanship of the nation.

As per usual, the rest of the Q&A is restricted to paid subscribers. If you are not a paid subscriber and learned from or enjoyed this post, then check out the benefits of membership on the blog’s about page. You may also follow the prompts below for a free trial.

Remember to send in your question for the next Q&A here. The more questions I get the sooner we can run another issue!

MS asks: “If the US were to redesign the constitutional amendment process, what changes would you make? What do you think of replacing the ratification by states with a national referendum at the next presidential election with a supermajority requirement of say, 60%, possibly with a second confirmatory referendum in another 4 years? Perhaps also lowering the threshold in Congress from 67% to 60%? My basic idea is to make the amendment process more similar to the states' while still keeping the threshold sufficiently high given that constitutional amendments are serious business.

This is a very creative question! I don’t think anyone has asked me about this before.

The first thing I thought of was to identify what is wrong with the amendment process today. That is a temporal question: when did it stop working? The latest controversial and substantive amendment was enacted in 1964 when Congress proposed and 42 states ratified the 24th amendment which prevented states from requiring citizens to pay poll taxes before voting. (Only Mississippi rejected the amendment. Legislators in the other states simply did not vote on it.)

So, let’s say the Constitutional amendment process started to break down sometime in the mid-to-late-1900s. Maybe it is harder to propose amendments now because the nature of our disagreements is more partisan, and our legislators are more driven by their partisanship. If that’s the case then I like MS’s suggestion of lowering the threshold in Congress from 67 to 60%, since the share of voters you need to win to prove you have “convinced” the other side naturally decreases with polarization. But 60% is also arbitrary. Why not 55%? 57%? At least 67 has the benefit of being 2/3.

Still, I think the national referendum is a better idea. That is what most other democracies do! It’s important to remember that much of our Constitutional order being structured around the consent of states is a vestige of the Articles of Confederation. Equal state suffrage, for instance, only really exists because New York and Virginia needed the buy-in of Connecticut and New Jersey to form a proper national union. The Amendment process is the same.

But for a national referendum, a 60% threshold seems quite high. Much like the filibuster, I imagine it would prevent the majority from getting what it wants most of the time, which is the fundamental principle of democratic, republican government. If you’re going to mandate a confirmatory referendum two years later then 50% seems like a good threshold. If not, maybe 51%. Anything else strikes me as a violation of the majority rule because it is too burdensome. Maybe you could require some percentage of Congresspeople to vote to introduce it first.

Sufficed to say a referendum does seem like the way to go. A bonus is that referendums is how New Zealand managed to change its electoral system from first-past-the-post single-winner districts (what we have) to mixed-member proportional representation in the 1990s. Maybe we could do that here. It is important to have an amendment process that is divorced from Congress because it is not likely that legislators will vote for their undoing (as many wouldn’t get re-elected in an MMP system, because of statewide elections, ideological concerns, or both). I would guess that there is a correlation between a country having a national referendum and an electoral system that rewards the numerical majority, not the majority of states.

Jonathan asks: “What can we learn from the recent Australian election? It seems like similar shifts are happening in political affiliation in the USA and Australia, but the different electoral systems mean we get more information in Australia (where there is ranked-choice voting)”

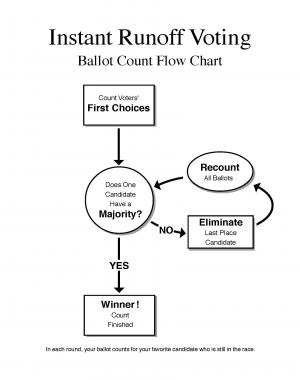

For those who don’t know, Australia had a national parliamentary election last month in which the four-time-incumbent conservative government lost power, replaced by an outright majority of Labor members. Australia uses a variant of ranked-choice voting called “preferential voting” (or, elsewhere, the “instant-runoff” vote) to decide who wins in each district. Here is a flowchart of how votes are allocated to each candidate:

IRV works well in Australia where traditional “liberal” voters are split between the center-left Labor party and the Greens, who are only really popular in cities. This means that liberals do not suffer as badly from the “spoiler effect” in elections, where a third-party candidate draws support predominantly among voters who prefer one candidate — such as with the Liberal Democrats and Labor in the UK. And the system of ranking means it is almost impossible that the Parliament is controlled by a party that won a minority of the preferred vote.

Needless to say, I think this would work well in America. Even better would be the use of ranked-choice voting to elect multiple candidates in broader Congressional jurisdictions (such as at the state level) via the single-transferrable vote (STV). This is what Australia uses to elect the members of its upper House. This generally leads to more proportional outcomes in legislatures, by which I mean parties that win 20% of the vote general win 20% of seats, too.

You can imagine how that would benefit Americans, who are currently split into two broad camps and elect legislators who listen only to a small minority of them. (NB: One heuristic is that a Republican Senator only believes they represent the Republicans in their state, which means at best ~25% of people are being represented in a competitive state — and that’s assuming they care what people think in general.)

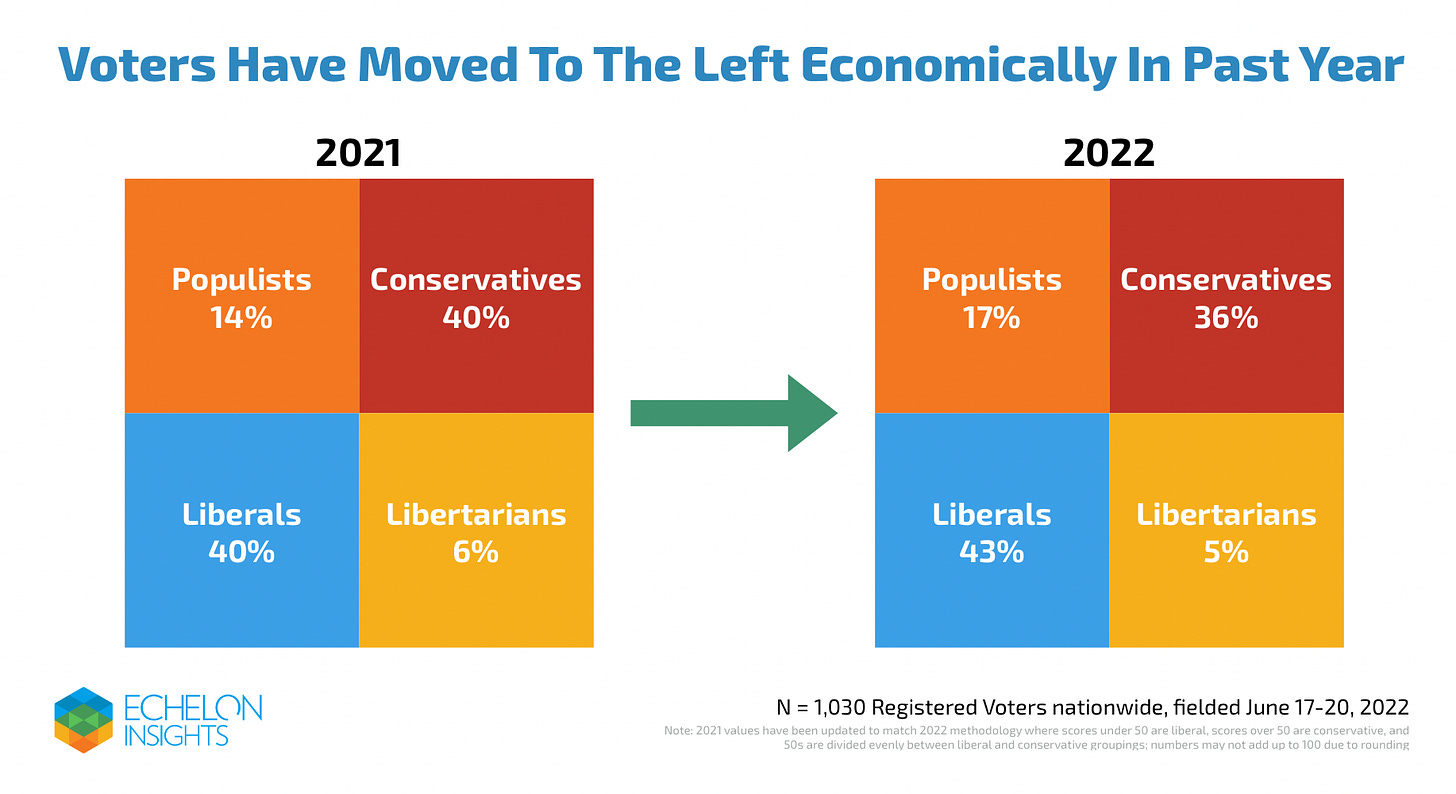

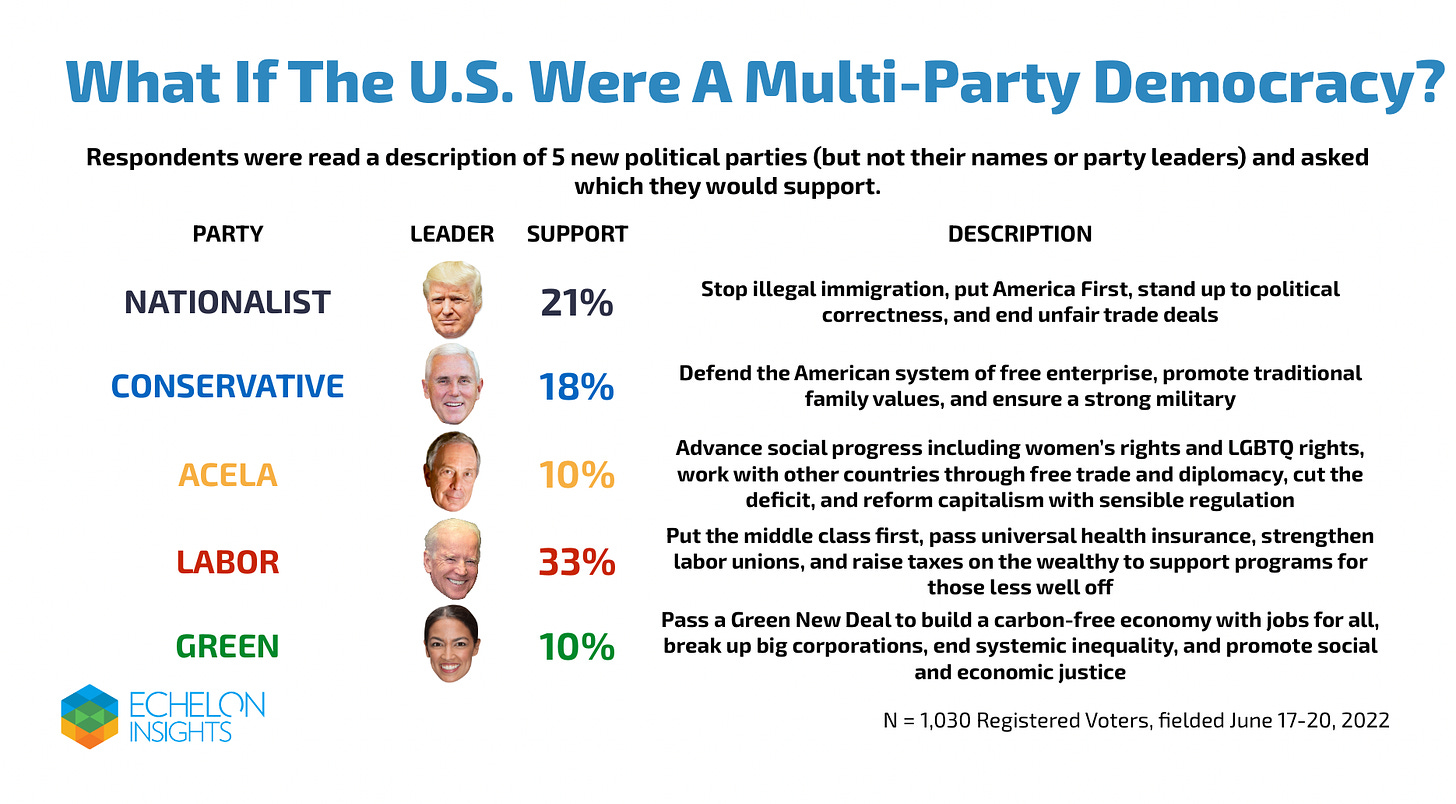

Adopting a system that assigns representatives via IRV or STV would likely lead to more parties in America, especially if you increase the size of the House. Recent polling suggests there are at least 3 and maybe as many as 5 competitive parties:

And when you give Americans more options for parties, they generally split pretty predictably: with the highest proportion of voters choosing the economic center-left, but a large number picking the far-left and nationalist/far-right, too.

The other point to make is that multiparty systems tend to lead to less zero-sum thinking among partisans. That’s because, when no party has support from the outright majority of voters, they have to work together.

Ranked-choice and proportional electoral systems are generally better at translating political inputs to government outputs in pluralistic societies.

That’s it for this week. Thanks to everyone who sent in a question and everyone else for reading. I am sorry if your submission was not answered. I will try to fit it into the next Q&A.

If you’d like to submit a question for the next issue, you can do that here!

This is an insightful article about what European nations' parliamentary systems have over the Canadian system and the USA system. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/02/world/americas/canada-gun-buyback-parliament.html.

Thanks for sharing!