How Democrats can break the midterms curse 📊 March 21, 2021

Economic growth and high approval ratings could forecast better-than-average success for the Democrats

Thanks as ever for reading my weekly data-driven newsletter on politics, polling, and democracy. I invite you to drop me a line or leave a comment below with your thoughts. Remember to click the ❤️ under the headline if you like what you’re reading. If you want more content, I publish subscribers-only blog posts around twice a week.

The midterms question

A reader named Bill asks…

I've been wondering about the right way to think about the net effect of — on the one hand — Biden's coming into power at a time where meaningful improvements in most Americans' lives should materialize and implementing popular policies, and — on the other — the conventional wisdom that suggests midterm dynamics (plus the effects of redistricting) are likely to cost Democrats their House majority. What is your intuition on this question?

That’s a good question — and one I had been planning to blog on anyway! So here you go, Bill

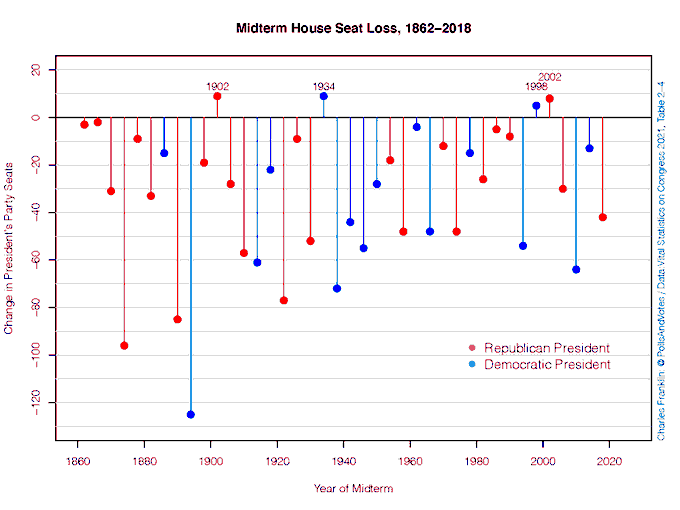

The party that controls the White House has lost ground in the House of Representatives in all but four midterm elections since the Civil War. Since 1946, there have been 19 midterm elections, and the party in power has lost seats in all but two of them: 1998 and 2002.

The average House seat loss in all of these years is about 27 seats, according to data analyzed by Charles Franklin, a Marquette University political scientist and pollster. In the Senate, the party in power usually loses about 4 seats, but it often does a bit better. Here is the above graph in table form:

From a starting point, this is a pretty bleak forecast for the Democrats. They will have to perform better than the average party to survive the negative pull of midterm gravity. Can they pull that off?

It is way to early to know. But that hasn’t stopped people from hazarding guesses. CNN’s John Harwood published an article this morning that asks “Can Biden make it 'the economy, stupid' again?” In it, Harwood quotes Biden’s pollster John Anzalone as saying:

If we've learned anything the last few years," said top Biden pollster John Anzalone, "it's that all the rules get thrown out the window."

The direct link between the pandemic and destruction of normal life, he argued, will magnify Biden's payoff for ending it. This month's rushing river of Covid relief money, including the $1,400-per-person checks now flooding into tens of millions of bank accounts, makes the effects of government action unmistakable to Americans across the political spectrum.

"He's going to be rewarded for a combination of leadership and an incredibly focused plan on Covid," Anzalone said. Though Biden's overall job rating remains lower, 60%-plus approval for his handling of Covid points toward the potential for political growth.

Anzalone is a good pollster, and I think his answer here covers the upside for Biden pretty well. But we need to be clear that it is, indeed, the upside. It takes a lot of fuel for a spaceship to escape Earth’s orbit; it will take a lot for Biden to lead his party through victorious midterms. But it could definitely still happen.

Consider the four charts below. First, I show the (relatively weak) relationship between annual percent growth in real disposable personal incomes (RDPI) and the change in House seats won by a president’s party. Note the positive slope, which shows that 5% growth in incomes at November 2021 would translate to the Democrats losing about 10 seats in Congress, whereas a decline of about 2% would lead them to lose closer to 50 seats. Current growth in RDPI is 4.5%.

There are two things to point out here. First, the slope is driven quite hard by the 1974 midterms, when Republicans lost 49 seats in the House and the annual change in real disposable income was -2.1%.If we remove that point, the slope is much less harsh. Today’s RDPI growth would predict a decline in House seats of about 12, enough to give Republicans control of the House, if the elections were held today.

The state of the economy, however, is an increasingly weak predictor of both election results and presidential evaluations. Although there is a weak relationship between the two historically, both presidents Obama and Trump saw their approval ratings become nearly untethered to the University of Michigan’s index of consumer sentiment. See the graph below, which I made for The Economist in the middle of 2019:

It is reasonable to take away from the above charts that whatever growth Joe Biden can cause from his $1.9T economic stimulus/covid relief bill will not automatically translate into electoral success. Even if real disposable income was growing by 10% over the last year, Biden could still lose the White House. It’s clear that there is something else at play here.

Rather than focus on economics, political scientists prefer to see midterms as political referendums on the party in power. If they have enacted popular policies and kept their base active, they do well. If they have not, they suffer (often quite severely) from a backlash by the engaged opposition.

One way to track Democrats’ fortunes, then would be to focus on presidential approval ratings. The chart below shows the relationship between popularity and net change in House seats for the party controlling the White House, since 1946. We see a slightly tighter relationship than we saw for the interplay of economics and midterm results, but there is still plenty of deviation from the trend line. In this case, a president with a 68% approval rating is favored to win more House seats than he had before the midterms. All else will usually lose, with the chance of surviving a wave approaching 0 for a president with an approval rating lower than 45%.

Joe Biden, however, is a relatively popular president by modern standards. A +15 net approval rating (55% approve v 40% disapprove, in my most recent averaging) is nothing to scoff at. He might yet be able to overcome the brutal punishment a midterm usually confers upon the ruling party. If Biden can improve his approval rating to 60%, which will be hard but is not entirely out of the question, the Democrats might be able to survive in the House.

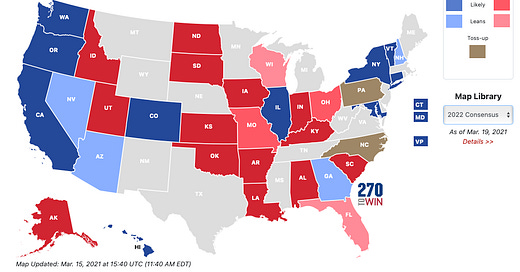

The Senate, meanwhile, could be a bit harder, given Democrats are up for re-election in potentially competitive races in Georgia, Arizona, Nevada and New Hampshire, though they could pick up Pat Toomey’s (R, retiring) seat in Pennsylvania.

…

Since 1946, the3 party in power has emerged from midterm elections with more seats than it had before them roughly 10% of the time. Ten is not zero — but it is rather low. Democrats’ best hope to boost their odds is for Biden to remain a relatively popular and mobilizing party leader. If Congress keeps passing bills that 70% of the country supports, and Biden can escape the flop in midterm turnout in 2010/14, Democrats may have a pretty good shot at holding on.

…

The answer to the final part of Bill’s question, sadly, is that Republicans might just gerrymander their way to a majority anyway.

Posts for subscribers

March 19: Moving off the gold standard. Newer technologies in public opinion polling are now routinely beating "gold standard" methods

Click here for the usual Sunday subscribers-only chat.

Want to hear more from me? Subscribe for extras by following this link:

What I Wrote

I wrote about a Pew Research Center report from last July that found that One-fourth of Asian Americans said that they feared someone would threaten or physically attack them because of their race. One third said someone had targeted them with a racial slur or “joke.”

What I’m Reading

Here is a great read by Atlantic contributor David Litt about a little-known episode of American history when the US House got rid of their equivalent of the Senate filibuster.

I thought this piece by FiveThirtyEight’s Perry Bacon Jr was an insightful explanation of why Republicans have gone all-in on the culture war stuff.

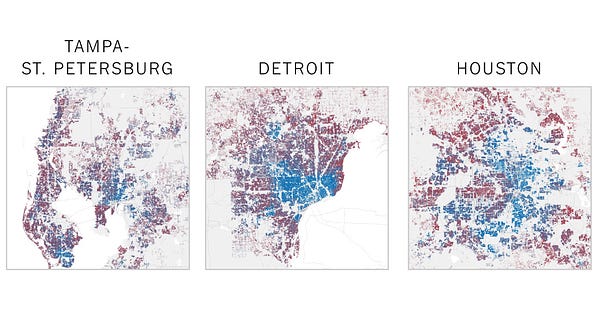

Emily Badger, Kevin Quealy and Josh Katz at the Times created a series of maps from a new political science paper that shows how segregated Americans are by their political affiliations, even within neighborhoods:

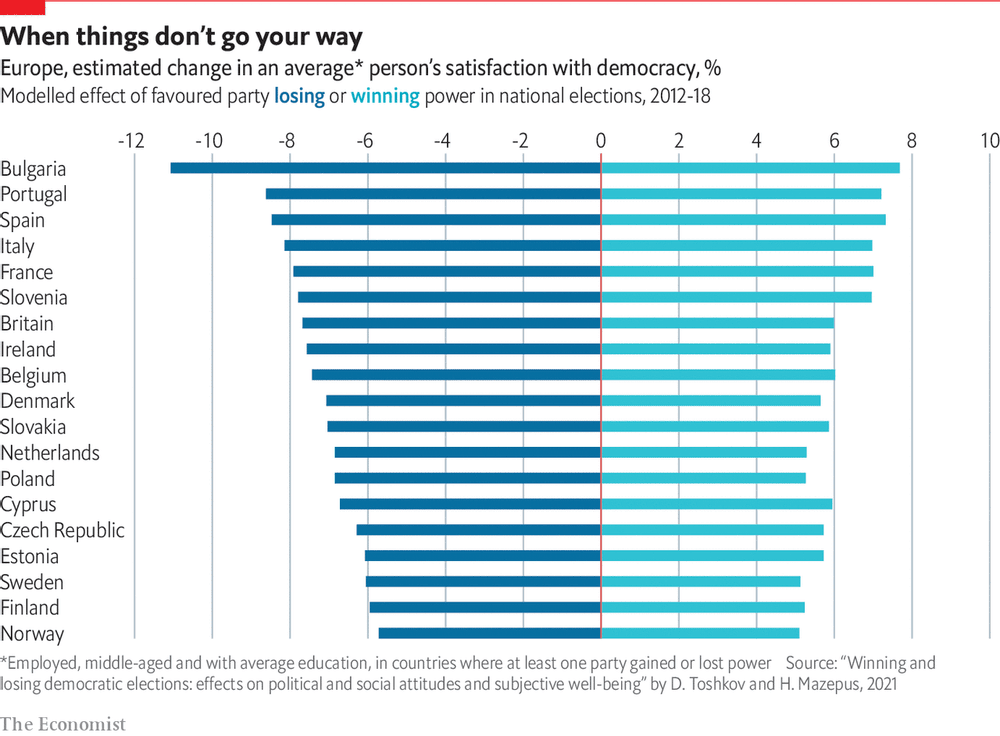

Finally, here is a piece by my Economist colleagues writing up a paper that shows voters who support losing political parties become more critical of democracy:

Feedback

That’s it for this week. Thanks so much for reading. If you have any feedback, please send it to me at this address — or just respond directly to this email. I’d love to hear from you.

If you want more content, you can sign up for subscribers-only posts below. I’ll send you one or two extra blog post-type articles each week. As a reminder, I have cheaper subscriptions for students.

In the meantime, follow me on Twitter for related musings.

Hi Elliott,

Great piece here! Presidential approval ratings are crucial. One Senate race, you did not mention is Wisconsin, where Senator Ron Johnson may or may not run for reelection. As a former Wisconsinite, I'm skeptical of it ultimately flipping. I'm not sure about Democrats' chances in North Carolina either.

-Elliot

Hey Elliott - what would be your preferred alternative to our current congressional voting system to combat gerrymandering (I assume you have one)? I see a lot of chatter about ranked-choice, though I'm not sure that helps in a funky district shape. Proportional representation would make if all house elections were statewide, but I assume there'd still be ways to game the system...