Who died and made Plato the king of Athenian democratic ideation?

Plato’s warnings against mass enfranchisement too often overshadow his pupil’s iterations

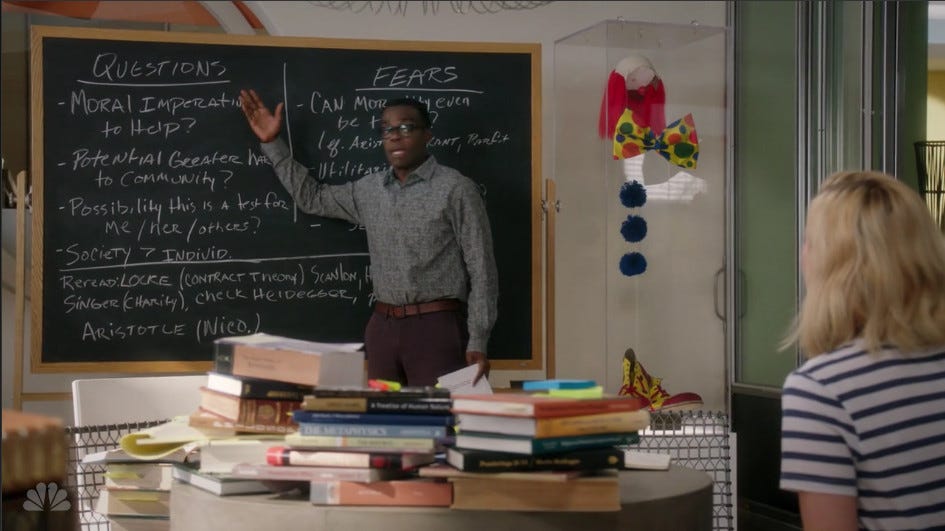

The title of this post is a riff on a particularly funny joke from The Good Place, one of the better shows to air over the last decade. one character, Eleanor, asks “Who died and made Aristotle king of ethics?” to which Chidi, a dead ethics professor, says “Plato!” Ba dum tiss.

That’s not really important, I just wanted you to know so you didn’t think I actually had a good sense of humor.

The purpose of the post is to draw a contrast between Plato’s and Aristotle’s philosophies on democracy and equal suffrage. Now, I am not an expert in either ethics or philosophy, but (a) I touch on this subject in my forthcoming book and found a passage from Aristotle that got me thinking, and (b) I got a lot of feedback on yesterday’s post essentially saying “Joe Biden shouldn’t do stuff just because it’s popular, he should do stuff cause it’s right” or “Oh, sure, because we can really trust the people to make good decisions about the government.”

These are common retorts to my reporting on the polls, so I replied what I usually do, which is that the things that are popular are also usually “right.” The subject of how the public comes to those decisions, what makes them “good” or “right,” is one that I am generally familiar with and one that pundits often get wrong, so I thought I’d write about it briefly.

Plato, Aristotle’s teacher and author of The Republic (perhaps the most well-known document on political philosophy aside from the American Declaration of Independence) was a famous skeptic of mass enfranchisement. This is not a history lesson, but you should know that Plato argues (controversially!) that governments follow a predictable path from oligarchy, to democracy, to tyranny. (It is important to note that “democracy” in these terms is similar to what we’d call today “direct democracy,” where every citizen — more or less — actively participates in the political process. )

Again oversimplifying a bit, Plato’s primary argument that democracies descend into tyranny, and so should be avoided, centre around a sort of political physics. This is GOV 101. People will form themselves into multiple factions with many different perspectives on government. To get elected, a politician will seek to flatter (or to stoke anger among) those factions, giving rise to demagogic leaders who will manipulate the masses to “overmaster democracy.” The probability of tyranny increases when things get bad; when people accrue to much wealth and power, when there is an external military threat or internal strife, etc. But the chance is always there.

To Plato, the crowd, with its passions easily prone to whipping up by a nefarious leader, is no place to seat political power. He has a few proposed alternatives which I won’t get into now. The point, in the simplest of terms, is that he doesn’t trust the people and doesn’t like democracy.

This point gets circulated a lot, often breeding characterizations of the Greeks (and their philosophy) as skeptical of the people. That is true on average; given the aristocratic backgrounds of most political thinkers, they are usually averse to populism. But (and now arriving at the goal of this post) this is not always true, and there are some important exceptions.

Namely: Aristotle!

Plato’s student was much more sympathetic to the idea that the people could make good decisions about the direction of the state. He thought the people to be wise, especially in aggregate. He wrote:

It is possible that the many, no one of whom taken singly is a good man, may yet taken all together be better than the few, not individually but collectively, in the same way that a feast to which all contribute is better than one given at one man’s expense. For where there are many people, each has some share of goodness and intelligence, and when these are brought together, they become as it were one multiple man with many pairs of feet and hands and many minds. So too in regard to character and the powers of perception. That is why the general public is a better judge of works of music and poetry; some judges some parts, some others, but their joint pronouncement is a verdict upon the whole. And it is this assembling in one what was before separate that gives the good man his superiority over an individual man from the masses.1

The quote above, from Aristotle’s The Politics, is quite a large deviation from Plato’s thinking on the dangers of crowds. It is worth dwelling on.

Plato’s “crowd” and Aristotle’s “general public” are two distinct concepts in the nature of democratic theory. The conceptualization of mass governance as taking place in an impromptu meeting of citizens, evoking images of a crowd of angry people trying a person and deciding to hang them in a public square, is quite a harsh image of “democracy.” But the terms “general” and “public,” both as Aristotle intended them and as we understand today, imply some mystical sort of unifying interest that binds the people together, and their decisions to the group. The crowd hangs a man for stealing bread from a neighbor; the public takes up a collection to buy food for people who have fallen on hard times. Later, Jean-Jacques Rousseau would formulate the theory of a “general will” that bound decisions to a collective “good” and steered the people toward doing what was right.

Now, Aristotle was not blind to the potential follies of democracy, but his view of public opinion (though it would not be called that until the 1700s) was of a collective will that pushed decisions (what we might call “policy” in today’s large states) toward the interested of the collective. Aristotle believed that, in aggregate, people could be wise — and certainly wiser than any one individual. Wisdom stemmed from the aggregation of individual “goods,” which canceled out randomly distributed “bads.”

Of course, this theory — which political scientists have come to call the “miracle of aggregation” — presumes certain conditions by which people come to their decisions. The idea that individual rationality points predominantly in a “good” direction while irrationally is randomly distributed among the population is not obvious to me. Given state propaganda, nefarious elites/thought leaders (which Greeks were also concerned about and called “orators”), and biases in the aggregation process (via elections, where not everyone’s voices are heard, or via self-interested representatives), it is likely this condition is never fully met one all issues in modern societies.

Still, rationality seems to win out over irrationality in most issues. Polls exhibit patterns of informed responsiveness to public spending, for example2 and the public has generally been a leading indicator of where the government should move on questions of rights for marginalized groups, including on expanding voting rights for black people in the 1960s and on allowing same-sex couples to wed throughout the 2000s and 2010s. People favor social safety nets and spending on public works programs, both of which are good for the general person — the “averaged American.” I will save more examples of the public’s rationality for another post.

…

Neither Plato’s nor Aristotle’s political philosophies were perfect. Often, in hindsight, they were even quite wrong. Neither really conceived of powerful, representative governments that could survive public strife, as ours do today. Any theory that is two thousand years old will have blind spots.

But the publicly interested ideas of the younger Greek are often overshadowed for the more skeptical warnings of his elder. That seems entirely unwarranted, especially given what we’ve learned about public opinion in the two thousand years since the two men wrote their treatises.

Aristotle, The Politics. Translated by T. A. Sinclair. Penguin Classics. Page 123

See Degrees of Democracy by Christopher Wlezien

Delicious image: "giving rice to demagogic leaders"

I'd make a distinction between public opinion when called upon to make a collective decision of consequence and more off-the-cuff queries about whatever is on the interviewer's mind.