What will Republicans take home from CPAC in Hungary? | #197 – May 22, 2022

The GOP travels to Viktor Orban's self-described "illiberal Christian democracy"

The news this weekend is all about a meeting of America’s Conservative Political Action Committee in Hungary. The meeting, which usually happens in America, departed from traditions to see what the right could learn from Viktor Orban, Hungary’s prime minister and an outspoken opponent of the free press, multiculturalism, and liberal democracy. Here are his own words, from a speech he delivered in 2014:

We have abandoned liberal methods and principles of organizing society, as well as the liberal way to look at the world. … This is about the ongoing reorganization of the Hungarian state. Contrary to the liberal state organization logic of the past twenty years, this is a state organization originating from national interests.

And, in a 2009 speech, he said:

a real chance that politics in Hungary will no longer be defined by a dualist power space. Instead, a large governing party will emerge in the center of the political stage [that] will be able to formulate national policy, not through constant debates, but through a natural representation of interests.1

At CPAC, Orban expressed his desire to work with Republicans in America to “take back” western governments from forces for liberal democracy. This is according to the Guardian:

“We have to take back the institutions in Washington and Brussels. We must find allies in one another and coordinate the movements of our troops,” Orbán said.

He told Republicans in the Balnaconference centre on the banks of the Danube that media influence was one of the keys to success. In Hungary, the prime minister and his allies have effective control of most media outlets in Hungary, including state TV.

“Have your own media. It’s the only way to point out the insanity of the progressive left,” he said. “The problem is that the western media is adjusted to the leftist viewpoint. Those who taught reporters in universities already had progressive leftist principles.”

He portrayed the US media as being dominated by Democrats, who he claimed were being “served” by CNN, the New York Times and others.

“Of course, the GOP has its media allies but they can’t compete with the mainstream liberal media. My friend, Tucker Carlson is the only one who puts himself out there,” he said. “His show is the most popular. What does it mean? It means programs like his should be broadcasted day and night. Or as you say 24/7.”2

While Viktor Orban’s crusade against liberalism and democracy has been well known outside of the United States nobody told the Republicans at CPAC. Yesterday Michaell Brendan Dougherty, a conservative writer for the National Review, sent a series of tweets saying that Hungary is, in fact, a liberal democracy, despite their prime minister’s statements otherwise:

Dougherty’s tweet immediately prompted others to note Orban’s past statements. They are arguing, in effect, that Hungary is not a liberal democracy because their leader doesn’t say it is. That is certainly one way to describe it, but I think it’s useful to take some time to ask: what is liberal democracy, anyway?

Traditionally, liberal democracies are characterized as states where citizens are treated as equals; where everyone has equal access to the vote; where they have an equal say in free and fair elections; where the press is free, with some guidelines, to write what they want about that government. They combine Liberal principles of government with constitutionally democratic states.

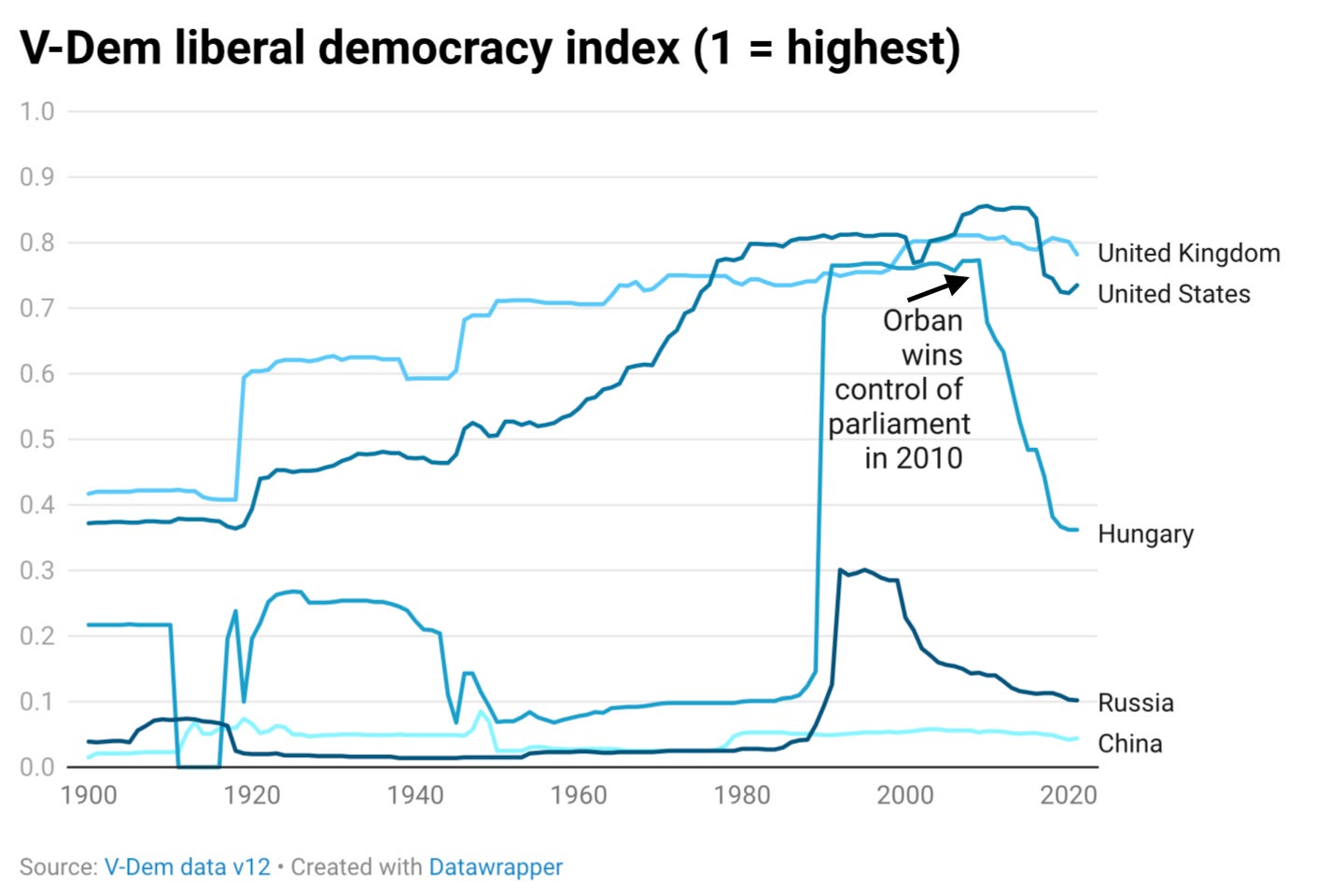

Ok. It might be easier to think about things that violate our understanding of liberal democracy. Certainly, China is not a liberal democracy; there is no partisan competition there. And Russia isn’t either, as there are seemingly no checks on the president’s power, and criticism from the press is forcibly restricted. The United Kingdom probably is a liberal democracy. So is the United States, with some notable exceptions (which we’ll get to).

But… you know what would make this really easy? Is if there were a way to track all of this information across time, and for different countries. If a country has a free press, they get a point toward liberal democracy. If they let everyone vote they get a point. If they have an electoral system that is reasonably proportional to outcomes, they get a point. Etc.

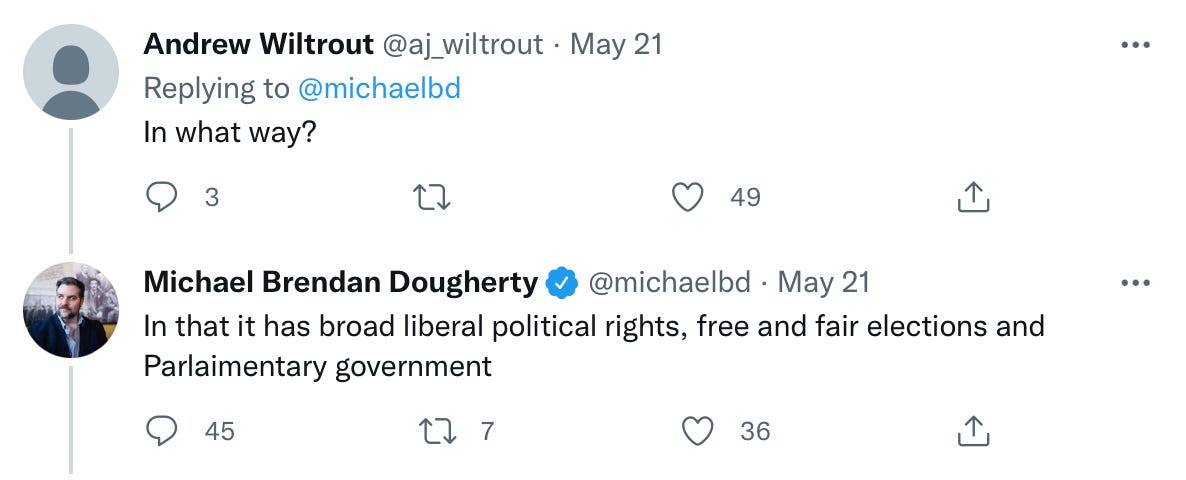

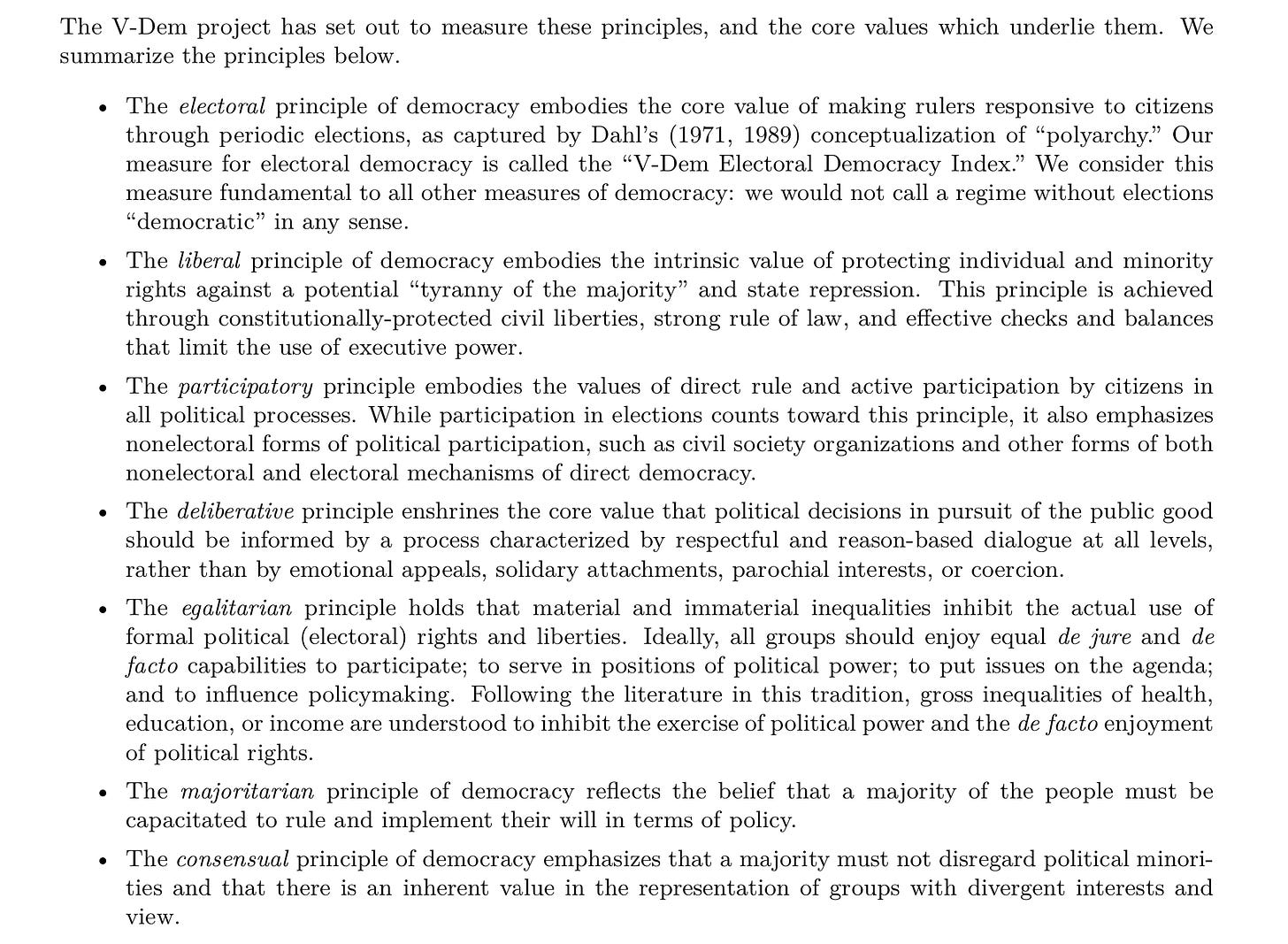

Lucky for us, political scientists thought of this long ago! The V-Dem, or “Varieties of Democracy” Institute at the Swedish University of Gothenberg, has been publishing ratings of each country on a “liberalism” index for some time. Their methodology is to ask a group of experts to grade each country on a variety of measures (picture below) and then use a statistical algorithm to create overall grades for them all. You can read more about that here and here.

V-Dem’s current ratings for every country look like this:

And here are what the rankings over time look like for the UK, US, China, Russia, and Hungary. I have added a vertical gray line at the year Viktor Orban’s Fidesz won power in Hungary, in 2010:

How well does this rating do? If your threshold for “liberal democracy” is a ~0.8, 0.7, or even 0.5 on the V-Dem index — which I guess would be a country about halfway between China and Norway — then Hungary is no longer a liberal democracy. That certainly fits with everything we know anecdotally from the news. Hungary has essentially banned opposition media. He has given out government contracts to his allies and rescinded those for his critics. Orban has called for a Christian nationalist state where Roma and Jewish Hungarians are not welcome. In July 2018 Orban gave a speech in which he described a remaking of the nation — not just the state — in an illiberal, socially conservative image:

Christian democracy is, by definition, not liberal: it is, if you like, illiberal. And we can specifically say this in connection with a few important issues — say, three great issues. Liberal democracy is in favor of multiculturalism, while Christian democracy gives priority to Christian culture; this is an illiberal concept. Liberal democracy is pro-immigration, while Christian democracy is anti-immigration; this is again a genuinely illiberal concept. And liberal democracy sides with adaptable family models, while Christian democracy rests on the foundations of the Christian family model; once more, this is an illiberal concept.3

Again, not very liberal! And the V-Dem metric does a pretty good job capturing Hungary’s slide toward illiberalism. Or, if you like, toward authoritarianism.

Of course, we don’t have to rely on their metrics. At least in determining the “democracy” part of liberal democracy, we can just study actual election results.

One thing that happens often when states slide toward authoritarians is leaders rewrite electoral rules in their favor. This lets them hide under a veneer of democratic legitimacy. Before Hungary’s elections this April, I wrote a piece for The Economist that looked at the real-world consequences of Viktor Orban’s electoral reforms after he took power in 2010. His party passed a constitutional amendment to redraw electoral district boundaries with a simple majority vote of parliament, and the results speak for themselves. In 2010, Fidesz did modestly better in districts with large populations than in less populous ones. After, the results were sharply the opposite, with Fidesz outperforming in small seats in the countryside, which gave them an edge in parliament.

We generated a hypothetical seats-votes curve for the April election and found pronounced differences in the share of seats that Fidesz and its opposition would have won at the same share of the vote. In April, the opposition probably needed 54% of the votes to control parliament. Fidesz could hold on with just 43%. This showed how Orban has successfully rigged Hungary’s electoral system in his favor by violating the principles that one person gets one vote, and all votes count equally.

. . .

These two exercises show how statistical analysis and data can be used to grade the performance of countries on various metrics of liberalism and democracy. They also show two different methods of analysis. One is hard math, the exercise of analyzing whether one party has a structural advantage in an electoral system — and whether it encroaches on principles of fairness and majoritarianism inherent in republican, liberal democratic government.

The other method is to ask smart people what they think democracy means, whether they think countries meet those standards, and to aggregate their answers using algorithms that remove biases from any one individual. In Hungary’s case, they are pointing the same direction.

And this brings us back to the question of what CPAC was doing in Hungary anyway. Are they there to learn more about policy proposals that can help their constituents? Probably not, judging by the speaker lineup. Are they there to learn about democratic electoral strategies that can win more voters and help them recapture Washington in 2022 and 2024? In a way. But the ideas in the marketplace were, inherently, more of the illiberal variety.

Viktor Orban’s move against pluralistic, majoritarian, democratic (or "republican, if you prefer) government look eerily similar to the proposals on offer from America’s Republican Party today. I wrote on Thursday about a proposal from a Republican candidate for governor of Colorado that would establish an electoral college for statewide offices. It would have given Republicans a double-digit victory in the most recent election despite losing by 11 points in the popular vote.

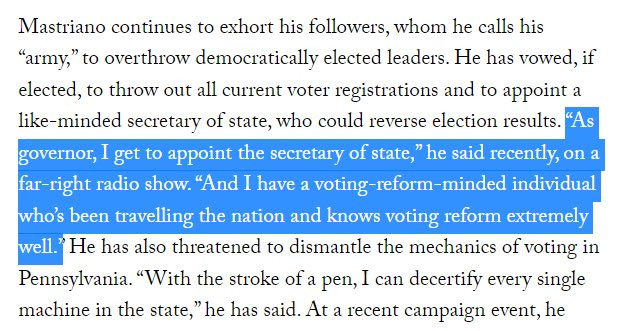

This week also brought the story of several 2020 election-deniers winning primaries for the GOP, including Doug Mastriano, a Pennsylvania state senator who is perhaps the most dangerous of the lot. Here is a particularly troubling quote from him:

That, too, is neither liberal nor democratic.

Talk to you all next week.

Elliott

Posts for subscribers

If you found this post satisfactory, please share it — and consider a paid subscription to read additional posts on politics, public opinion, and democracy.

Subscribers received two extra posts over the last week:

That’s it for this week. Thanks very much for reading. If you have any feedback, you can reach me at this address (or just respond directly to this email if you’re reading in your inbox). And if you’ve read this far please consider a paid subscription to support the blog.

https://verfassungsblog.de/illiberal-democracy-beyond-hungary-2/

https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2022/may/20/viktor-orban-cpac-republicans-hungary

https://www.journalofdemocracy.org/articles/illiberal-democracy-and-the-struggle-on-the-right/