What people are missing about the state of the polls—and the polling models 📊 September 26, 2021

There are two types of errors leading the poll-watchers astray, and it's mostly not their fault

This is a free weekly edition of my personal newsletter. If you like it, please share it. If you want to read more of my work on polling and democracy, consider a subscription to the blog. I write private posts roughly twice a week.

Some polls are good and some polls are bad. You need to look under the hood to really tell the difference.

This is part of my philosophy about polling. I have formed it over years of producing, studying, and processing polling data. But this is, apparently, a contentious statement. Other polling aggregators — FiveThirtyEight (538) and RealClearPolitics.com (RCP), for example — essentially subscribe to the theory that all polling data is roughly comparable, and averaging this data together even without the knowledge of what’s producing it will produce optimal estimates of public opinion. I have been told by other analysts that aggregating data “warts and all” can reduce bias among constituent polls without introducing other big problems. But recent events suggest this is not the case.

Take the 2016 and 2020 elections. Then, the polls experienced varying degrees of uniform bias that made the aggregates systematically underestimate support for Republican candidates. The forecasters blamed the pollsters on average for this error. But the truth is that some pollsters did better than others. Studying the reasons for this led us to better predictions for the future.

In 2016, the pollsters who didn’t weight their data by educational attainment had too many educated (white) voters in their samples and overestimated Hillary Clinton’s share of the vote nearly across the board. We know the error was related to educational attainment in part because errors were worse in states with higher concentrations of less-educated white voters. We also know that the polls showed several phantom swings towards Clinton that were caused not by people changing their minds in who to vote for, but by changing shares of people who were taking surveys. One way to counter this is to weight your polls to some set of benchmarks for the percentage of Democrats and Republicans in the electorate.

So, when planning forecasting models for 2020, it would have been reasonable to add adjustments for these things. You could program your model to observe the systematic differences between estimates from pollsters who used the correct set of weights and those who didn’t, then adjust for it. Indeed, when we ran our models after the fact for 2016, we came up with much better predictions when we let the model correct data from pollsters with subpar weighting schemes towards the figures from pollsters with good weighting. In 2020, this also reduced our bias, though we had errors elsewhere. (All of this modeling is a matter of public record, by the way.)

Yet, 538 and RCP did not do any adjusting. They stuck to their philosophies that bias toward Democrats or Republicans in the polls would cancel each other out on average. As a result, when the polls were systematically pro-Biden in 2020, so were the models. They would have almost certainly been better if they up-weighted data from the pollsters who weighted by education and party, even if this would not have removed all of the bias.

But they repeated their mistakes this month. When the 538 average of polls in California showed a 16-point margin for keeping governor Gavin Newsom in the state’s recall election, it was partly because of their inclusive, undiscerning approach to processing polling data. The result of the recall looks likely to land around +24 points for Newsom — making the 538 average eight points off on margin, 4 on vote share.

“That’s huge, it’s way bigger than the polling miss in 2020 or 2016,” FiveThirtyEight’s CEO, Nate Silver, said on the site’s politics podcast this week, “but no one cares” because the polls landed on the right side of 50/50. (Polls were off nationally by 2 points in 2020). Polls got the winner right, so people are moving on. I will add: even if you adjust the surveys for the fact they had undecided voters in them, artificially pushing the polled result away from the Democrats, some were still off by double digits.

In fact, the story is not that all the polls were wrong, but that some were wrong — and 538’s model wasn’t programmed to know the difference. A better model (here’s mine at 59-60% “Keep Newsom”, for example), would have used the information going into the polls to be able to tell the difference.

So let’s use this opportunity to talk through two big errors in the public conversation about polling. One about methods, and one about interpretation. To anticipate one error of interpretation: my point is not that polls are in good shape, because many are not, but that we can be smarter about how we analyze them.

I. Not all polls are created equal

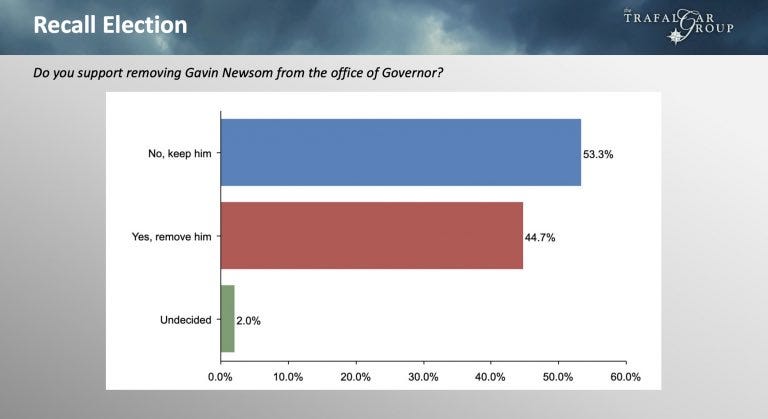

Let’s begin with an example. FiveThirtyEight gives an “A-” rating to a polling firm named Trafalgar Group based on its record of supposed accuracy between 2016 and 2020. The polls have a “mean-reverted” bias towards Republicans of only 1.3 points, Nate Silver’s accounting says, so deserve a high grade and corresponding weight in their models.

This is puzzling and obfuscating, however — not because Trafalgar’s polls have been pretty terrible recently, but because they have an opaque methodology that produces implausible results. One poll has before found 30% of African Americans would vote for Donald Trump, for example (the real number is around 8%) and another showed Trump winning young people by 14 points (he lost them by 30). The group has previously deleted polls from their website and not released new ones, one sign of shady stuff going on behind the scenes. Their president is a regular guest on Fox News, where he claims the pollsters and mainstream media are rigged for liberals — conduct that isn’t typical for high-quality public pollsters. There is a two-pronged issue here: first, that the data are generated by a clearly subpar process, and second, that there’s reason to believe that process would be biased towards Republicans. (Which the rating system confirms.)

So when Trafalgar released a poll showing the campaign to recall Newsom only underwater by eight points in late August, 538’s model saw its “A” rating and adjusted their aggregate heavily in that direction. It did the same thing when the firm released a 9-point in mid-September.

One alternative would have been to hedge against it — either statistically, via a model that puts more weight on pollsters who have transparent methods (ones that are at least members of the official association for pollsters!), or via cutting them out of the aggregate because you can’t trust their data. When you don’t do this, you are implicitly asserting that the data-generating process (DGP) for Trafalgar’s polls is just as reliable as the DGP for other pollsters. That is a false assertion. But in fact, 538 goes further by implicitly saying the Trafalgar DGP is better than most other ones, because of their high “A” rating. And that’s a recipe for disaster—for a 16-point error skewing a polling average.

The insistence on treating polls as equal upon entry can lead us into making some pretty rough mistakes beyond trusting a clearly biased and subpar pollster. Sometimes there are just errors in the way a poll is conducted that warrant caution. In some cases, they even warrant removal. That’s what happened with one poll of the California recall from an otherwise credible pollster called SurveyUSA. They made an error in their question wording that caused the sample to be systematically too Republican — pretty much the inverse (though with a much higher magnitude) of what happened in 2016. FiveThirtyEight refused to remove the poll from their average even after the pollster admitted the error. If they had, their trend lines would have been much more reasonable.

On the other end of the spectrum, the pollsters that weighted their data with more complex weighting schemes (such as YouGov, Data for Progress, and Emerson college) had lower errors in the recall than those that didn’t (such as SurveyUSA, Gravis Marketing and “Core Decision Analytics”, whoever they are), though he pollsters that had a lot of experience in the state (like the Berkeley IGS poll) also beat the average. But if mainstream polling models were able to control for the differences between these polls and others, they would have done better. The moral of the story, in one crude sentence, is that not all polls are created equal. The best methods also change over time, and in ways that simply comparing the results of a poll to the results of an election don’t capture. Our best models should know that.

Further, conventional wisdom should factor in these differences. Regular readers of the polls do not need to make calls as to which polls are good or bad, how to create their average of what-have-you — they ought to simply be told that there are good and bad ways to conduct survey research, and that putting more weight on the good methods — not simply the more historically “accurate” polls — might lead them to a better understanding of politics.

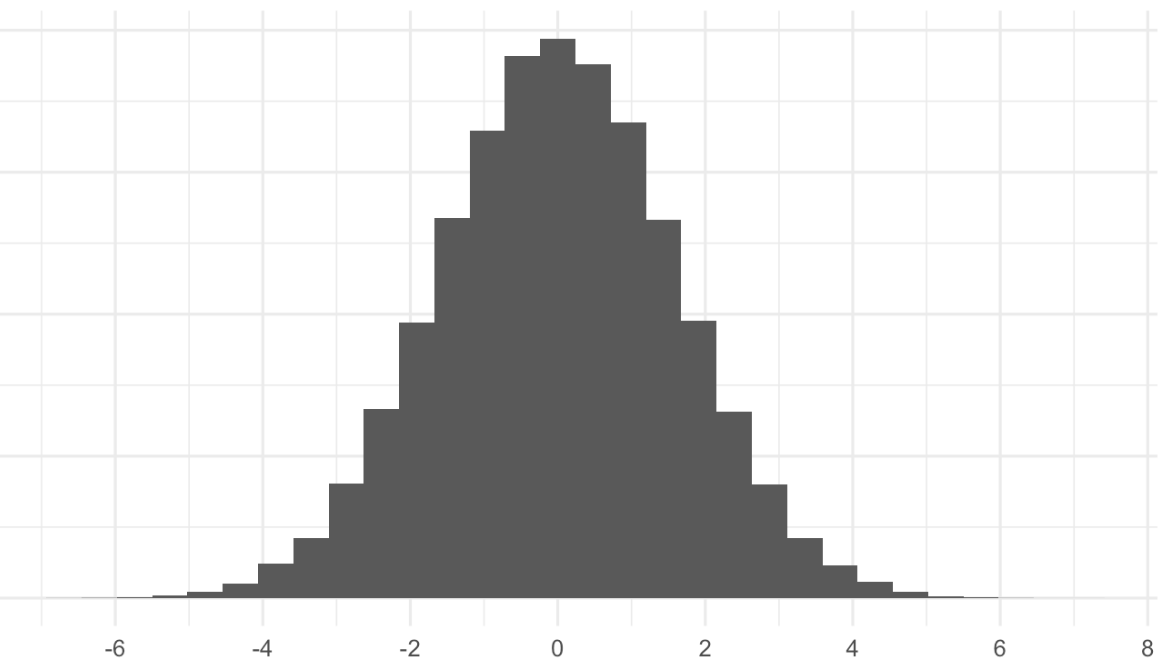

II. Take the margin of error and double it

The second category of polling error is that people expect too much precision from the polls. So much so that the 2-4 percentage point error has been described to me as a “massive failure” for the whole “industry” of pollsters. That’s despite the fact a miss of this magnitude would be well within the “true” margin of error for a poll — the one that captures not just sampling error, but the effects of non-response and weighting choices, question-wording, and sample coverage. For election polling, this “true” margin of error is roughly twice as large as the one you usually hear, according to a famous study.

But we’re looking at aggregate errors, not for one poll. They should be smaller, right? That’s right — but they still aren’t zero! When you combine the random variance in a set of ~20 polls (the population size for the California recall) with the propensity for most of them to be biased in the same direction, the chance that so few would all be systematically biased by 2-3 points (on vote share) is very high. I ran a set of simulations and got a probability of about 20% for bias >20 points in either direction.

My argument is not that a 2-4 point miss isn’t large, but that poll-watchers should be made aware of how often they happen. Preferably, analysts would communicate this. The smart ones already know about the confluence of bias and variance and can be clear about them to readers. It would be easy for 538 to put margins of error on their polling averages, for example. But pollsters could also be more transparent about the (un)likely probability of big errors in survey research. At this point, we know that publishing a normal 3-point margin of error for a 1000-person poll is too small. So pollsters should publish bigger ones, even with ad-hoc adjustments. Political reporters should demand that information.

This is all to say that the (good) polls are usually pretty good — so long as you’re not expecting unreasonable degrees of precision. Public opinion polling is both a science and an art, the typical contrast goes. And there is a pretty reasonable balance between the two on average.

. . .

To summarize quickly: while it is true that many pollsters have a long way to go correcting their methods for recent patterns of bias, the polling analysts can also be smarter when they communicate about the data they're relying on. They could also be more accurate and honest about the limits of their methods and of the polls themselves. Both would go a long way to improving the public conversation about polls and ensuring people trust the industry on average to do the thing it really needs to do: communicate the will of the people to our leaders.

And on that subject, subscribe to my newsletter to read this post from earlier in the week. We dive deep into the polling on coronavirus vaccinations and measure whether the data are accurate or not.

Posts for subscribers

If you like this post, please share it — and then consider a paid membership to read more in-depth posts from me.

Subscribers received four extra exclusive posts over the last two weeks:

On deck: There is much to say about the popularity of the progressive tax plans and the declining popularity of Joe Biden, which could bleed into efforts for reform.

Thanks for reading

That’s it for this week. Thanks so much for reading. If you have any feedback, you can reach me at this address (or respond directly to this email if you’re reading in your inbox). I love to talk with readers and am very responsive to your messages.

For potential subscribers who are sticker shook, email me and we’ll set you up with a free trial. As a reminder, I also have cheaper subscriptions for students. Please do your part and share this article online if you enjoyed it.

I get the sense that the folks at 538 have an aversion to making manual adjustments to the data feeding into their models (or in the case of the recall election, their polling avg.) because it feels like they'd be introducing their own biases into the model. But to your point, not making these adjustments allows for biased data to sneak in & gives the casual reader/the 538 analysts this false sense of fairness, since they're not making any ad-hoc adjustments/exclusions. There's certainly the case to err on the side of inclusion for edge cases, but I don't think the SurveyUSA was an edge case; given their recant, that should have been removed.

You are +/- 100% correct in your analysis re some polls are better designed and conducted than others. A lesson should be that pollsters need to be better educated. (Are there distinctions among highly educated white male pollsters and less educated pollsters, any color, gender, class? ;))