The cracked looking glass of public opinion polls 📊 April 18, 2021

Polls are often wrong, and sometimes meaningfully biased — but nothing else can do what they do.

Dear reader,

I am almost done with the revised draft of my book. I’m sure many of you want me to just print the damn thing already so you can buy a million copies, and maybe even read it. Me too! But the process is out of my control. I am told it takes months to edit copy and print galleys and send metadata to book sellers and get reviews and on and on. Alas, I am not the publisher.

The act of finally finishing my conclusions has colored my analysis of the polls this week. I am going to pull on a few different threads in this post, but hopefully it all comes together in a nice, neat package. The angle is: polls are great, but often flawed.

Separately, I have been thinking about how the public will react to the CDC’s pause on the Johnson & Johnson vaccine. Early signs are that aggregate hesitancy has not risen, which means demand for the Pfizer and Moderna shots will probably increase. I got my first Pfizer shot last week and am looking forward to regaining a sense of normalcy soon.

Not to brag or anything.

—Elliott

Thanks as ever for reading my weekly newsletter on polling, politics, and democracy. Drop me a line or leave a comment below with your thoughts. Remember to click the ❤️ under the headline if you like what you’re reading. If you want more content, I send out extra subscribers-only posts twice a week. Sign up here.

The cracked looking glass of public opinion polls

A friend sent me a James Joyce quote the other day, analogizing the link between the “cracked lookingglass” he calls Irish art and the imperfect reflection offered to us by public opinion polls. This is something I wrote about in the middle of my book, and it connects to various themes of the way polling gets incorporated into the news right now.

New polls released this week showed the public is broadly in favor of Joe Biden’s proposed $2T infrastructure bill, the American Jobs Plan. As I blogged on Friday:

Biden’s current push on infrastructure spending — defined loosely so far to include physical transportation infrastructure and funding for some social programs — is less popular, but still supported by a clear majority of Americans. 56% of adults register in favor of the bill, according to a new NPR/PBS NewsHour/Marist poll, while 34% oppose it. That works out to a +22-point margin for the American Jobs Plan, placing it among the more popular legislation of the last 20 years.

As is customary with most legislation, the Plan’s parts are more popular than the bill as a whole, which can often be dragged down by (a) out-partisan opposition to the legislation and (b) an increase in the share of people who don’t have an attitude on the whole bill, but still know how they feel about smaller proposals.

[….]

One interesting wrinkle in all of this is that the Democrats’ push for a more expansive definition of “infrastructure” might be decreasing public support for spending. A CNN analysis last week found that economic issues were a higher priority for the people. Another stimulus bill, then, might be even more popular.

Poll-watchers might be feeling the shock of whiplash comparing these numbers to those on the Trump presidency. His key legislative proposals — rolling back Obamacare and Medicaid, and passing the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act — were some of the most unpopular of the last half-century. To go from such an unpopular president to a widely popular one has left us to make a sharp adjustment to how we think about the relationship between the people, their representatives, and the government.

What is the public?

According to the polls, the defining feature of Joe Biden’s presidency so far has been his ability to persuade an apparent supermajority of the public to support a massive expansion of government investment in the economy, and our lives. His covid-19 relief plan was ultra-popular, and the stuff he is doing now/next is less popular but still supported by a plurality of voters.

This is a bit disorienting. Just two years ago, in Donald Trump’s America, we would have thought either (a) that the public did not feel similarly towards spending, given who was in charge, or (b) that the general will of the people was being betrayed by the government, and the electoral institutions that gave political power to an unpopular minority of voters was assigning different outcomes than people wanted.

Option (a) is unworkable. Had you defined “public opinion” as “the election results as expressed by the voters” you would have had to assume that somewhere between 2016 and 2020 there was a massive shift of policy preferences and/or issue prioritization that fundamentally reshaped the electorate, and who they wanted to win the election. This rests on an unhelpful focus on binary outcomes that obscures small differences in vote shares across years.

So if you instead define “public opinion” as the more wholistic “what all American adults want,” you will find a much lesser trend. Polls show that policy preferences on spending, immigration, health care and the like are very stable over the past few years. The thing that changed from 2016 to 2020 was not that everyone changed their mind, but that the population of voters was slightly more liberal on a few important issues, and soured on the president.

How progressive is it?

Polls are useful for uncovering this broader general will. They are, in fact, the only way to determine what a true majority of American people want. No mechanism of electoral accountability — be it Congressional election or referendum — replicates the democratic process of poll-taking.

Imagine what our conceptualization of the demand for social spending would look like if we were relying only on the results of the 2020 election instead. You might rationalize that, since Trump got 47% of the vote, only a bare majority of the country supported increased spending. But the polls say that the conservative position spending is only garnering support from 30 - 40% of the public.

On current issues, the polls have revealed the American people to be a lot more economically progressive than we would otherwise think. The fact that we know this will help them get what they want from their government.

But what if the polls are wrong?

There is a good chance that many of them are — to an extent. The Pew Research Center released a report a few weeks ago that found by being biased in the political composition of the electorate (eg, who people said they were going to vote for in November), they were underestimating conservative/Republican issue positions by one point on average — though some points were biased by as much as three points (or six points on margin).

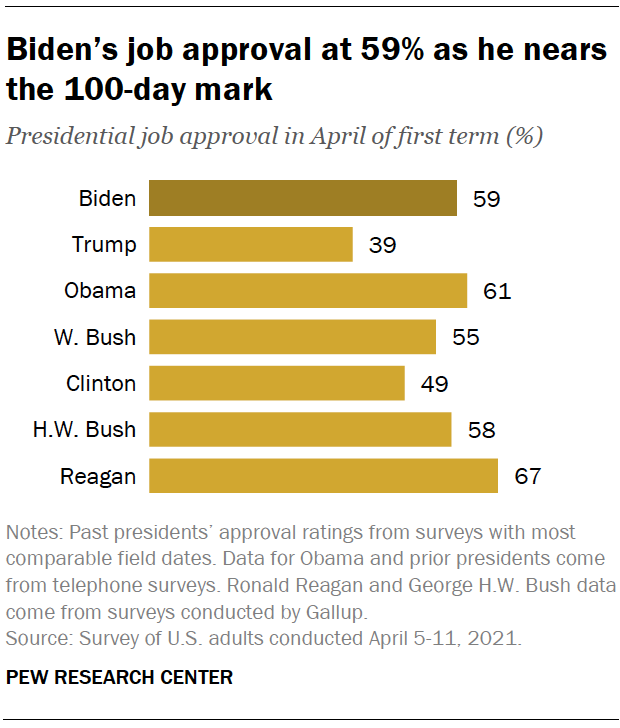

That is enough to reverse the verdict of a recent poll from Quinnipiac, for example, which showed that Biden’s newest bill was only net popular by 6 points. (Other polls and ways of asking the question have it as more net-popular.) Similarly, given the polling miss last November, it is not far-fetched to think the polls are underestimating President Biden’s disapproval rating.

But what does a three percentage point bias mean in the real world?

The good news is that most policy questions are not so evenly divided as to make that level of measurement error consequential, especially when given proper context. The people paying attention to polls don’t change their behavior based on a three point difference. Even the shift between 60 and 65, or 65 and 70, percent of people being in favor of infrastructure spending is not a meaningful difference to high-level decision makers.

It is also worth remembering that very few people make their decisions purely based on the polls; for the White House and Congressional leaders, they are only one consideration.

The silent majority

If you rely on these polls, then, the adult population is almost a perpetual minority. They want gun control and more immigration and free public college and Medicare for All and all that stuff that came up during the 2020 Democratic primary. Maybe you think that relying on those polls are bad, so you tweet a meme like this making your argument:

There are several problems with this.

First, there are a lot of polls that say these things are popular! Based on them, the meme is probably wrong. They might be done incorrectly or have certain biases, but on average across time and space, the liberal position on these issues has either a plurality support or is tied with the conservative one. It’s not entirely clear to me whether I would make this meme in light of that evidence.

But second, policy preferences might not drive votes like you think. Political scientists have long characterized the public as “operationally liberal” but “symbolically conservative.” On matters of policy, especially economics, they are more progressive than not; but on social and cultural issues, and on issues of government scope and more abstract conceptualizations of Freedom, they are not. The latter are enough to outweigh the former sometimes, and that’s how Republicans win office. Things get easier when the electoral college tilts way to the right like it does today. So if you think the fact that Republicans win elections is a rebuttal of the polls, you might be making a huge mistake

Whether the meme is right or wrong also depends on your definition of “public opinion.” If you think the government should represent all adults, and you look at a simple average of polls, the public opinion is pretty liberal. But if instead you’re trying to win elections so are only really concerned with the population of voters, and are trying to play it safe with your data, the opinion might be more conservative. It really depends on what you’re trying to accomplish.

The reality is probably somewhere in the middle of these extremes. Liberal positions are not as popular as many people in the media assume, but the polls still show they’re pretty popular — pulling about even with conservative positions, depending on your definitions.

Another relevant point is that, historically, the government has played along and usually does what the people ask. Voters tend to elect candidates who are closer to them on the issues, though it often makes important misses.

The evidence here is mixed. The Democrats lost seats in the House between 2016 and 2020 because they appear ideologically farther from the median voter on salient issues, especially for branded politicians (“The Squad”). But they also elected a president who promised to do all of the things in that image.

Maybe the issue is just more complex than a meme?

The looking glass

These errors of definitions and measurement make it hard to see polls as ever providing a pure, absolutely reliable representation of the public opinion. There is no discoverable root truth of the general will.

To return to the looking glass metaphor, the polls offer up a distorted reflection of the American public to whoever gazes into it. There are cracks, yes, but also blemishes and imperfections that make it hard to see the portrait inside — and the process of squinting introduces both a straining of attention and a fuzzing of the peripheral context of our reality.

My defense, and the one the White House has apparently chosen, is that there is no better tool to tell you what the people — all of them — want from their government, and that the government should give them what they want most of the time. To many Democrats, that seems to include people who do not vote.

So, what does the public opinion favor? Are the cracks in the looking glass so severe as to prohibit accurate gazing, or are they shallow enough that a reflection can be recovered? The fact that the Democratic position on immigration and social spending hasn’t sunk Joe Biden’s approval in partisanship-weighted polls could offer a hint.

Posts for subscribers

April 16: The public is in the mood for big social spending. And they want corporations to pay for it

April 14: Will election polls be more accurate now that Trump out of office? A popular theory is that partisan non-response is going to disappear since Trump is not on the ballot. This misses the point.

Plus: the weekly subscribers chat on a few key issues of the day.

I also wrote two posts two weeks ago that I didn’t plug in last week’s newsletter: One on Aristotle and public opinion and another on trends in party affiliation.

What I’m Reading

Check it out: Penguin Random House sent me a copy of Julia Galef’s new book The Scout Mindset, which promises “A better way to combat knee-jerk biases and make smarter decisions.” I like when people send me books and I’ll probably write about it next week.

Also, check out this cool interactive on Congressional apportionment from WaPo.

What Else I Wrote

Please read this piece from me on the long history of democratic backsliding in Republican-controlled states.

And read this 400-word item on public confidence in vaccines after the CDC suspended the J&J one-doser.

Feedback

That’s it for this week. Thanks so much for reading. If you have any feedback, please send it to me at this address — or respond directly to this email.

If you want more content, you can sign up for subscribers-only posts below. I’ll send you one or two extra blog-post-type articles each week. As a reminder, I have cheaper subscriptions for students and I’ll give you a free trial if you ask nicely.

In the meantime, follow me on Twitter for related musings.