Links for January 8-14, 2023 | The C-SPAN effect; "socially liberal but fiscally conservative"; religious social sorting; and the happiest jobs in America

Abandon politics, return to logging

Happy weekend, subscribers.

This is my regular weekly roundup of articles/books/charts etc. I’ve read or media I’ve watched that I think are interesting and worth a fun discussion. This week is special in that we ponder the purpose of our working lives instead of just contemplating politics. (I’m being a bit dramatic; we look at BLS data instead of addressing politics alone.)

1. The issues that divided voters in the 2022 midterms

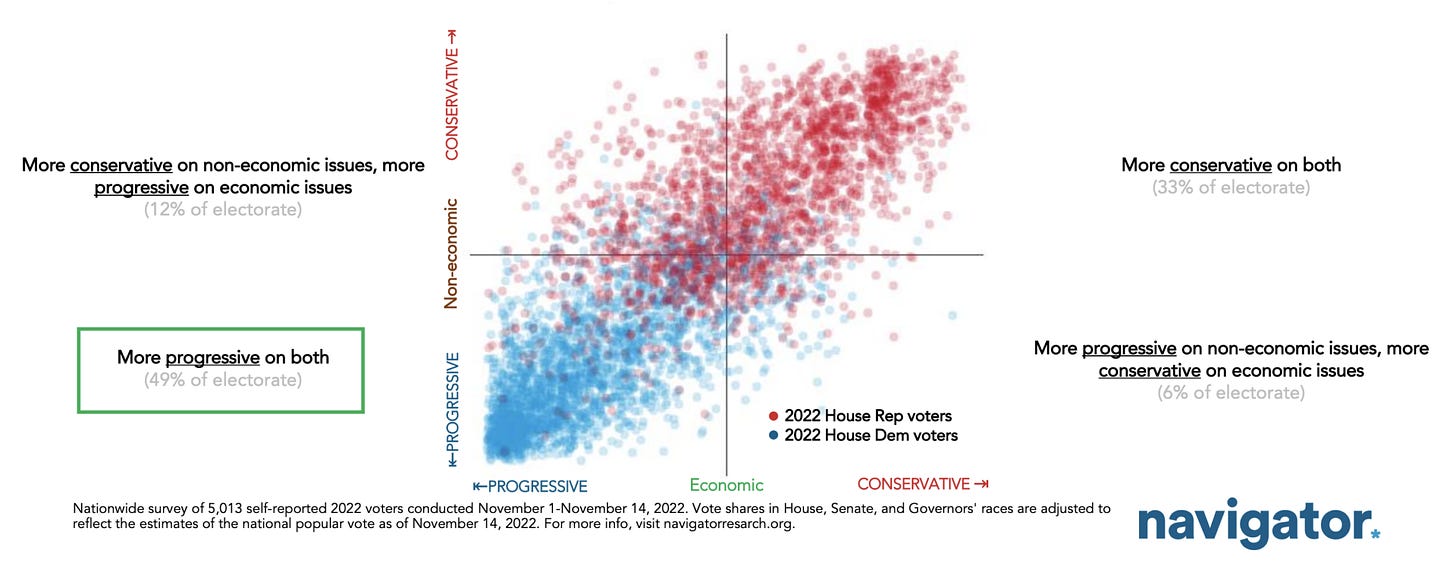

Navigator Research, which is a polling firm aligned with left-leaning candidates and causes, has analyzed the results of their polls from the 2022 elections and placed the American public on a two-dimensional ideological plane based on their respondents’ answers to many different policy and political questions. They find that the average voters hold progressive views across economic and non-economic issues, but those on the left are more politically divided than those on the right. “Those who were more progressive on both economic and non-economic issues (49%),” Navigator reports, “went for Democrats by at least 70 points in House, Senate, and Gubernatorial races; those more conservative on both (33%) were more consolidated behind Republicans by at least 85 points in all races.” Most importantly they find that “Voters who were more conflicted between economic debates and non-economic issues also backed Republicans by sizable margins.

The money chart from their report follows, showing how 5,013 Americans place themselves along economic and “non-economic” (sometimes called “social”) issues. You get the familiar progressive block in the bottom left, the conservative block in the upper right, and voters who have a mix of opinions in the upper left and lower right, depending on their orientations:

This is a familiar finding; Christopher Ellis and James Stimson famously find that Americans are “symbolically conservative but operationally liberal," meaning that the average voter calls themself a conservative but prefers liberal policies. That’s how you get more voters to the left of that graph yet Republicans won the popular vote for the House last year.

My take? The way Democrats win elections is by advancing liberal policies without calling them liberal. “Bipartisan” (as in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Framework) seems to be the new buzzword.

2. DeSantis Is Polling Well Against Trump — As Long As No One Else Runs

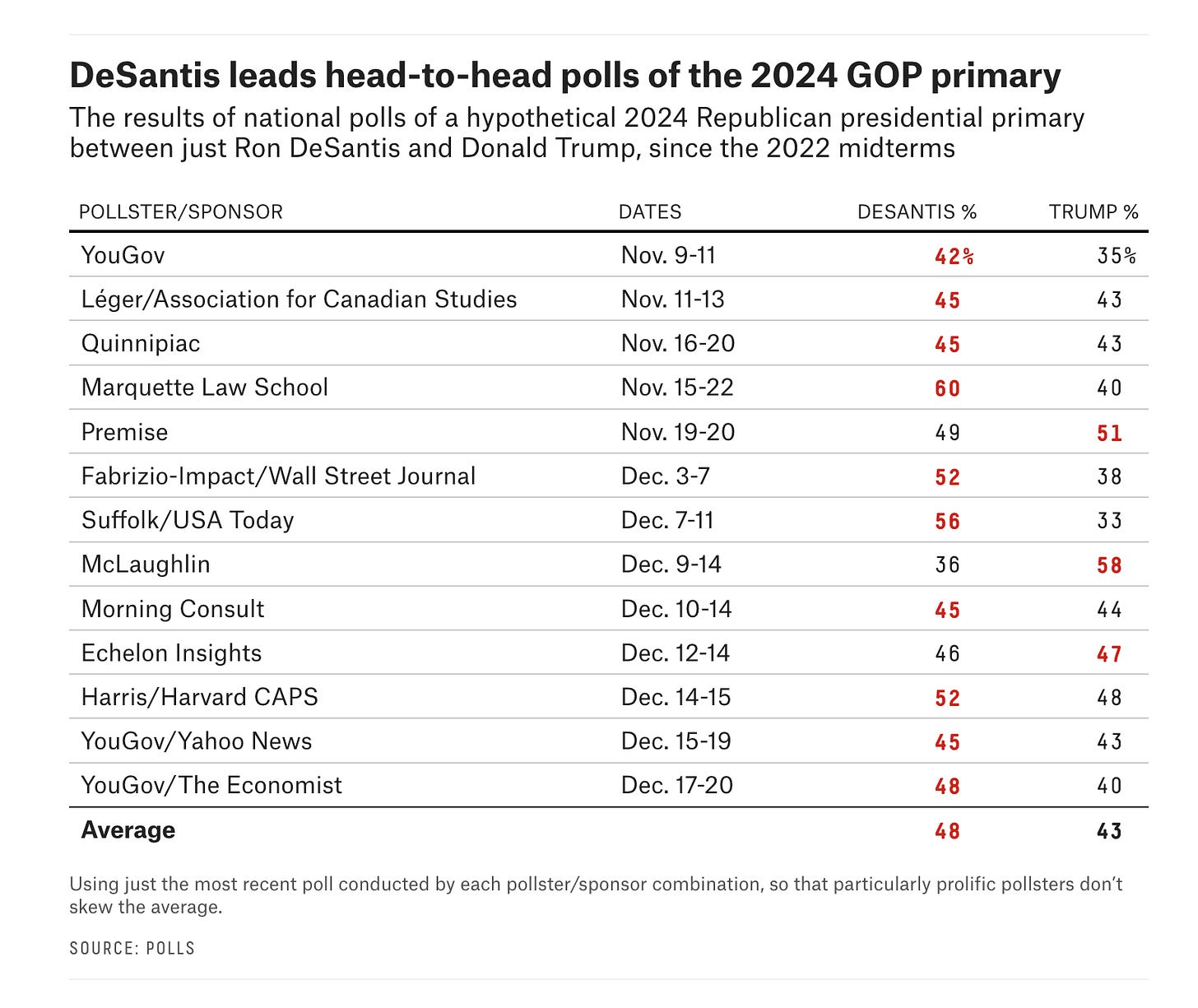

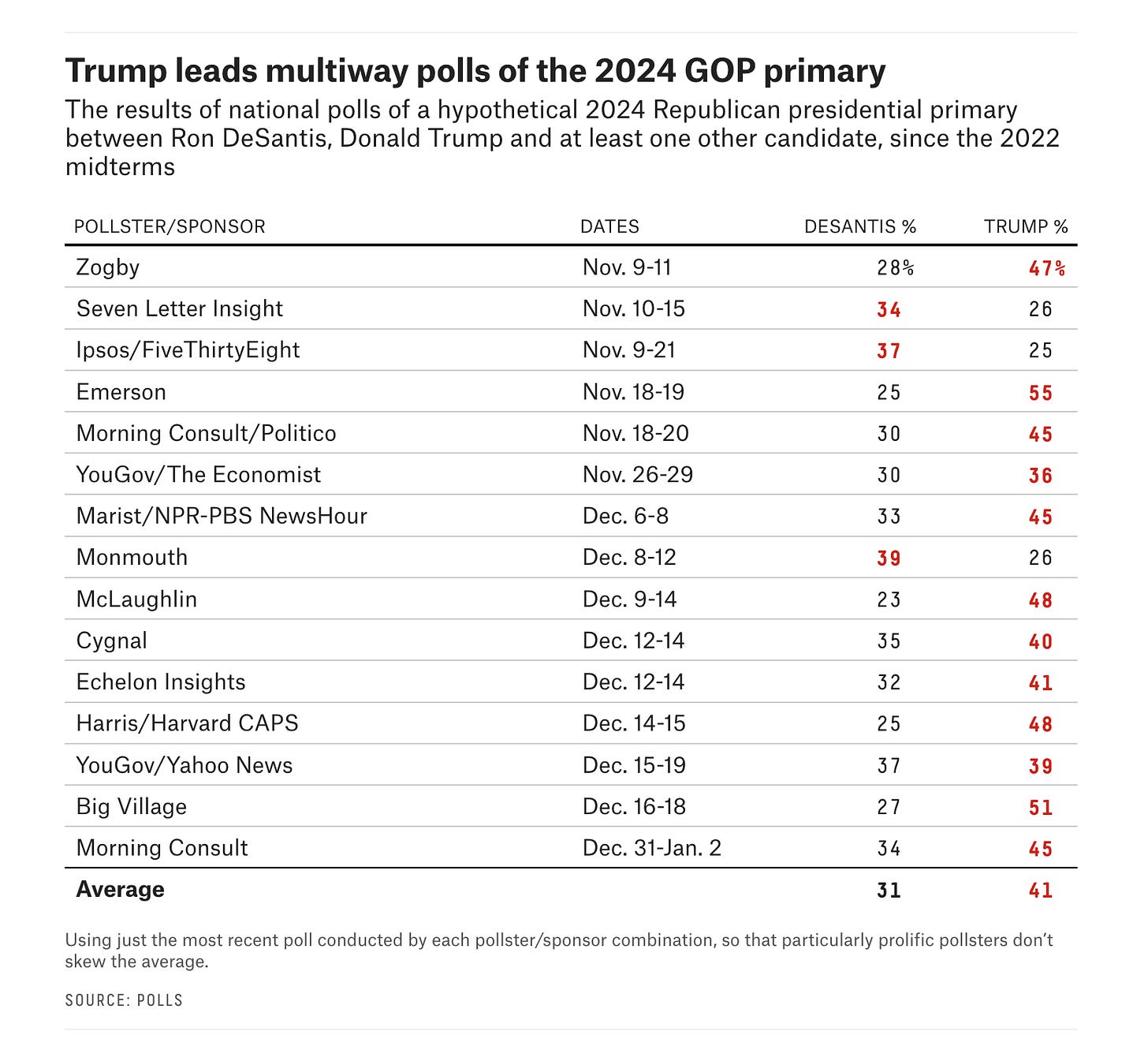

Nathaniel Rakich of FiveThirtyEight takes a very (very) early dive into polls of the 2024 Republican Primary and finds an interesting pattern. In surveys of the contest so far, when pollsters force potential voters to pick between Donald Trump and Ron DeSantis, the Florida governor came out on top — by about 5 points on average. But if respondents had a pick between Trump, DeSantis and at least one other candidate, Trump led by 10 points on average. Here’s the data:

When Rakich looked at pollsters who asked about the primary both ways, he found about a 10-point effect. That’s roughly consistent with the cross-poll look.

This is an important point — one that might sound familiar to people who witnessed Trump’s victory in 2016. This exact dynamic was at play; most GOP primary voters preferred someone other than Trump, but he was able to win a plurality of the vote in places that matter (namely, those states that pledged delegates on a winner-takes-all basis) and he won the primary. If a repeat of that contest happens again next year I think we can expect a similar result.

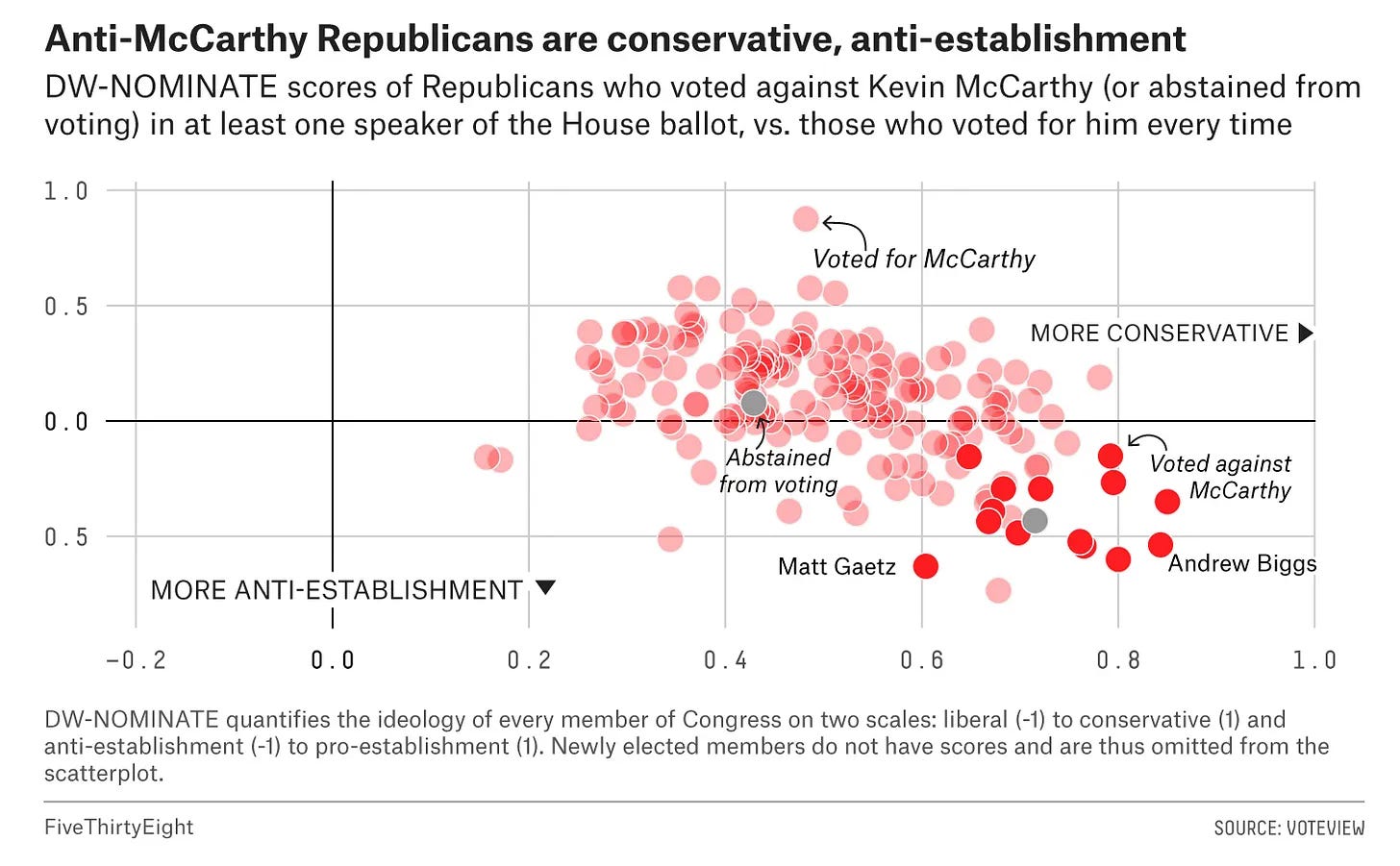

3. Voters like their representatives but don’t like Congress — and that’s how you get Matt Gaetz

Natalie Jackson, the pollster who writes the Leading Indicators column over at National Journal, writes this week about what, exactly, the #NeverKevin caucus wanted in the GOP speaker battle settled last week. “it was completely unclear to me what the 21 members who opposed Kevin McCarthy were fighting for, other than attention,” Jackson writes.

Instead of a group of legislators standing for a set policy or process differences, Jackson argues the members are all incentives to run against Congress. That’s because they’re from safe districts where voters don’t like the institution but do like their representatives; yes, including Matt Gaetz. Here’s a chart on that from last week.

Jackson writes “The same people who say they hate Congress continue to reelect their House members at the same rate they did in the 1970s—around 95 percent of incumbents roll right back into the chamber.” Continuing…

The phenomenon of disliking Congress intensely yet reelecting the same members election after election is so well known that political scientists have a name for it: Fenno’s paradox, named for Richard Fenno, the political scientist who first noted in the 1970s that people dislike the institution but like their own member.

This creates an incentive for Congresspeople to take actions that muck up Congress and make them look good in their district. That has a few profound implications for America’s next federal legislative sessions. The biggest is, of course, that the same infighting that animated the resistance to McCarthy’s speaker bid will make it hard for the majority to pass laws over the next two years. And with big fights over the federal budget and America’s national debt set up for the latter half of this year, we may soon see how ugly this gets.

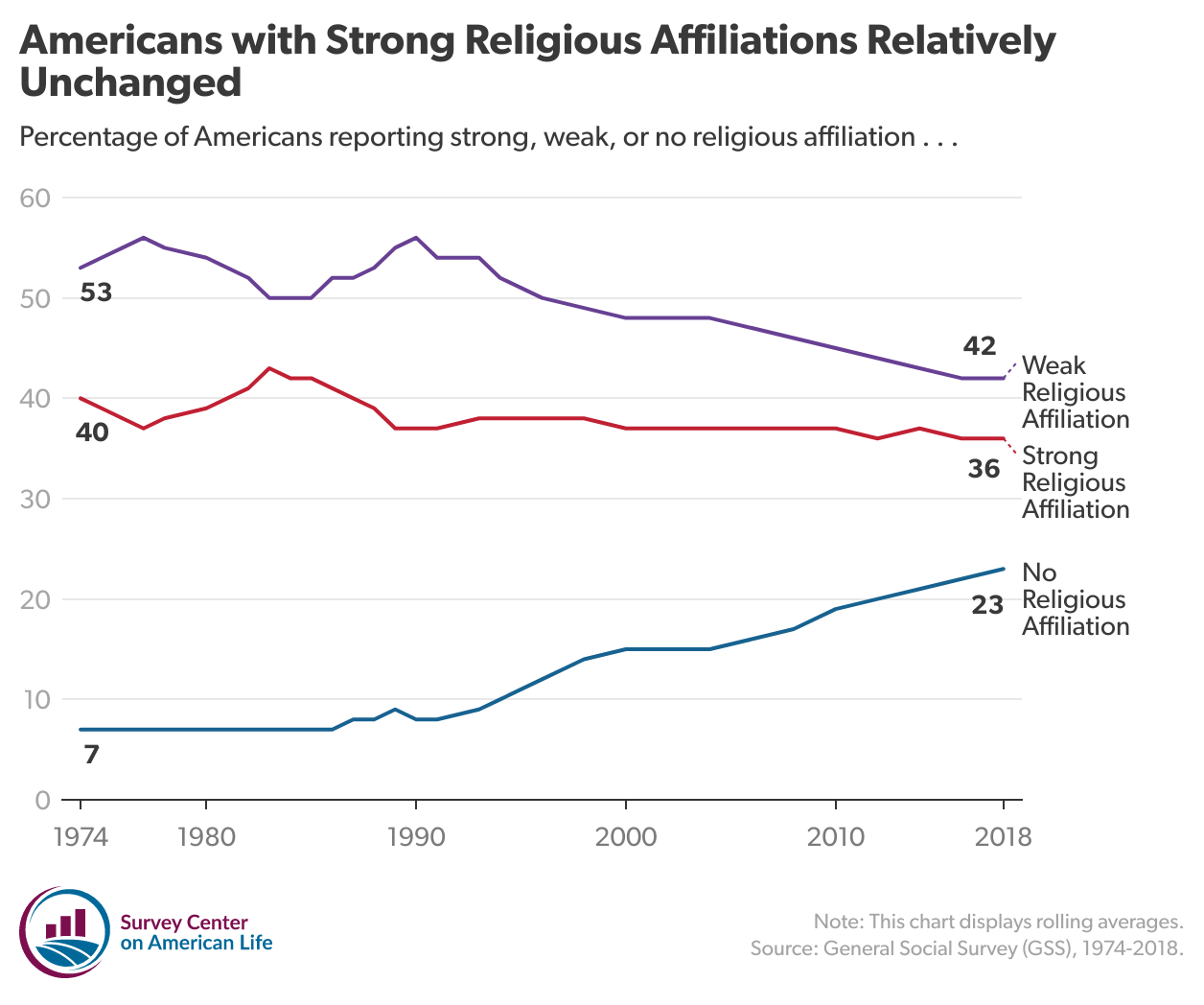

4. America’s states are becoming more and more set apart by their religions

My friend Dan Cox writes over at his substack about how the fracturing of religious identity in America is exacerbating our sense of different-ness from our far-flung national neighbors. The share of Americans who collectively have either no religious affiliation or a strong affiliation is at an all-time high, Cox shows:

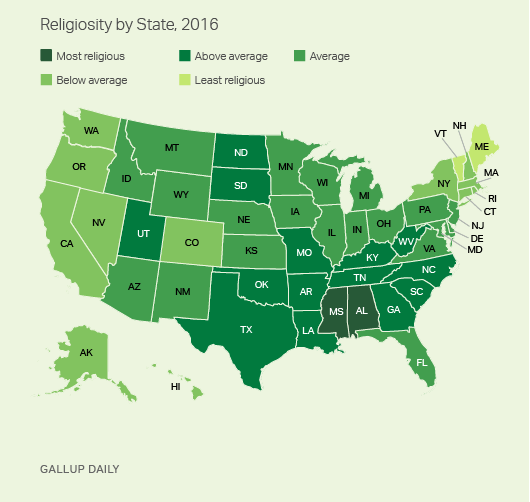

And this is happening while Gallup is finding religiosity at the state level keeps diverging more and more. Mississippi is the most religious state, where 59% of adults call themselves “very religious,” while Vermont is the least — only 21% say the same there:

Yet Cox writes “despite this gloomy portrait, there is good news.”

Americans still broadly affirm the value of religious pluralism and the principle of religious liberty. America's growing religious diversity also serves as a challenge to this narrative of religious polarization. But our religious differences loom larger than they once did. Fortunately, America has had extensive experience navigating religious difference and overcoming religious prejudice. We are certainly capable of doing it again.

This is interesting. I might agree with Cox if people in, say, Washington DC had anything at all in common with people in Mississippi or Wyoming. But, more and more, they don’t — and more and more, religion (or lack thereof) is one of the things that is driving us apart.

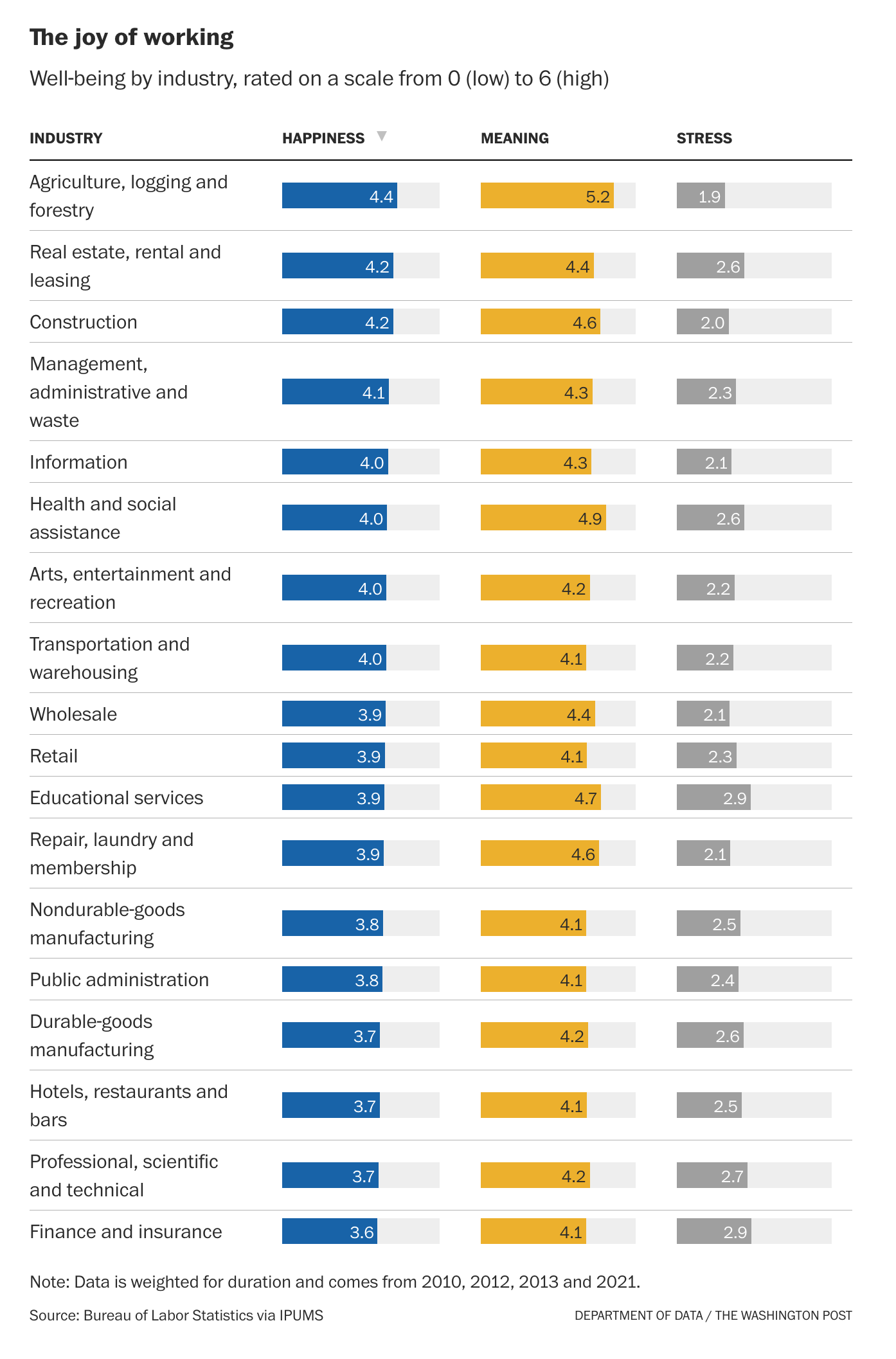

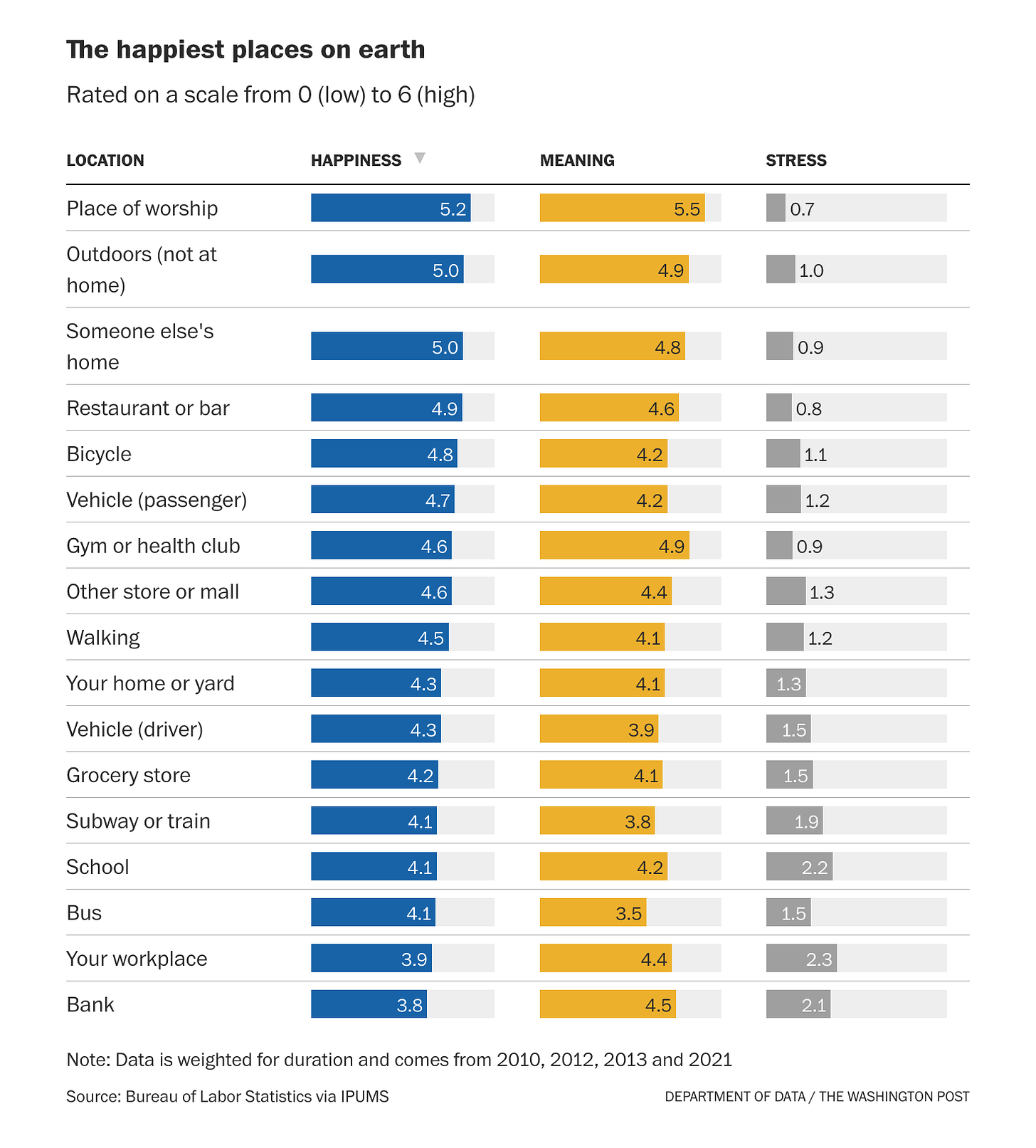

5. What job to do if you want to be happy

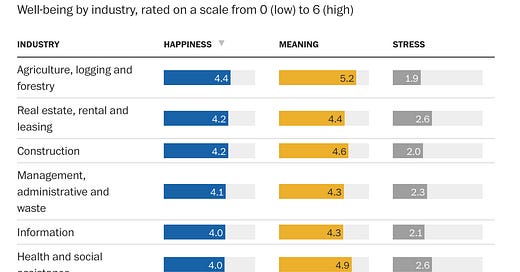

Cutting down trees is, apparently, a good option. Washington Post “Department of Data” columnist Andrew Van Dam takes a tour of Bureau of Labor Statistics data and computes how happy, fulfilled and stressed out Americans are based on what jobs they do. Workers in the agriculture, logging and forestry industries perform the best along these metrics, while workers in finance, law and hospitality rank lowest. (Tip your waiters extra.) Here’s the chart:

This is interesting to me, if for little more than it’s a break from the boring hum-drum of political numbers. What job should you do if you want to be happy? Now that is a good question. I had always thought I’d be good at wearing flannel and wielding a logging-strength chainsaw for 9 hours a day. But, unfortunately, the highest-rated industry is also the one with the most reports of injury over the last year.

That just goes to prove there’s no reward without risk.

Americans also get a lot of happiness and meaning out of walking, according to Van Dam. That does sound a lot safer than a chainsaw.

That’s it for this weekly edition of my top links. Thanks for reading and being part of the community that supports this newsletter.

I hope you all have a restful holiday and a good week ahead.

Elliott

It is possible that, at early election stages, some voters are willing to offer preferences among a few candidates but shy away from choices among a large number of candidates. In the past, it has been possible to assemble a ranking from a series of limited contests.

My take on a 2024 replay of the 2016 Republican nomination contest would have DeSantis winning. In 2016, as the contest winnowed out candidates without a base, Trump faced candidates who he could defeat one-on-one, Cruz and Kasich. In the pre-2024 multicandidate polls you list, DeSantis would always survive that winnowing, ending up facing Trump alone, a contest he wins.