First, let me extend a Happy New Year to you all, as this will be my last post of 2020. This year has been a hard one for many of us, and the holidays can be a constant reminder of the mental strain of isolation. I am hopeful that next year will be better and that I get to see many of you in person again.

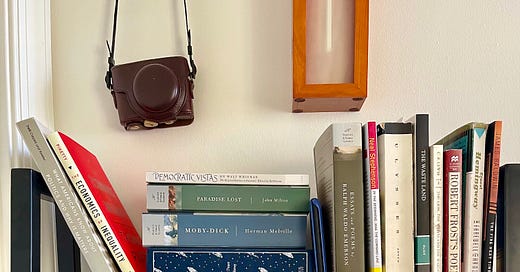

Now, for business: In keeping with the tradition of my blogging, this last post of the year is a recap of my favorite books that I read over the past twelve months. This exercise is useful as much as a reminder to me of what I read and learned as it is a recommendation to you of what I think you might get something out of.

One thing of note is that most of the books are about polls — or at least polling-adjacent. That is, of course, because I wrote a book on polls this year and needed a lot of source material. I consider this a bonus for all of you that have asked for recommendations about books on polls in recent months — but for those that have not, there are unrelated historical and political works mixed in here that most of you will like.

OK, here's the list of my most memorable reads this year — consisting of the book title and author as well as a short description/big of commentary on each.

The Averaged American, Sarah Igo: If you're looking for an engaging, well-researched history of survey research in America, this is the place to start.

The Wizard of Washington, Melvin G. Holli: Holli's history of a little-known political statistician who worked for FDR and the Democratic National Committee gives an interesting, machine-led perspective on the birth of public opinion polling.

Numbered Voices, Susan Herbst: Polls have changed the way that politics work in America and Herbst's book does a great job outlining how and why.

Survey Research in the United States, Jean M. Converse: The authoritative academic history of survey research (as a sociological and psychological tool as much as a political one) in America, first coming from Britain.

Athens, Christain Meier: An engaging and romantic review of what life in Athens, Greece was like during its "Golden Age." (Especially engaging for those of you who are interested in democratic theory, like I am right now.)

These Truths: A History of the United States, by Jill Lepore: I enjoyed Lepore's storytelling, and this is as good as any good single-volume history of the United States. However, one thing that irked me about These Truths is the tendency to reflect on the bipartisanship of the 1950s-70s a bit too romantically, as if discrimination against minorities from Republican and Southern Democratic elected officials was a means to a productive end. It has a good chapter on polls, though.

Lost in a Gallup, Joseph W Campbell: Pre-election polls have gone wrong before, and they will miss elections again. This book reviews some of the prominent misfires of the industry, and reflects (though not enough, in my opinion) on how the shortcomings of the news industry in interpreting polling data led to heightened perceptions of failure.

The Sum of the People, Andrew Whitby: A great story of where censuses came from, and what they're used for today. Highly recommend.

From Tea Leaves to Opinion Polls, John Geer: As Susan Herbst's book tells the story of how polls changed politics, Geer’s academic account reckons with how the availability of data on the public's preferences changes our understanding of the jobs our elected officials are actually doing. (More on that re: Lindsay Rogers’s book below.)

Democratic Vistas, Walt Whitman: What is there to say, really, about Uncle Walt's finest work? Writing after the Civil War, Vistas is a thought-provoking essay on the need for a unifying American spirit to allow the country to reach its great purpose. I can hardly disagree, though Whitman's case that "two or three really original American poets" can get the job done is more than a little oversimplifying, given what we know now about the weakness of our institutions.

The Pulse of Democracy, George Gallup and Saul Rae: Gallup and Rae's book is the classic defense of the promise of public opinion polls. namely as a "constant referendum" on the goings-on of the government. If you like it you might also like reading about Jeremy Bentham's "Public Opinion Tribunal."

The Pollsters, Lindsay Rogers: As The Pulse of Democracy demonstrates the normative promise of polling data, Rogers's The Pollsters illustrates the danger of handing the government over to them. Of course, nobody is really arguing for that, but Rogers's account of the decline of what political scientists have called the "trustee model" of representation is worth engaging with. If you read Gallup's book you should also read Rogers's.

The Public and its Problems, John Dewey: Another book on the weakness of letting the people govern. Dewey differs from most critics of popular democracy, however, in acknowledging that the people, in their sovereign duty, do contribute some useful opinions about the government. (Whereas Rogers, and Dewey's chief opponent Walter Lippmann, found little value, if any at all.)

The American Commonwealth, James Bryce (esp volume 2, "Public Opinion" chapter): Bryce's account of American democracy in the early late 19th century is a useful iteration upon de Tocqueville's Democracy in America. It's a sweeping portrait of America's emerging government behemoth, with all of the institutions that came along with it. While Democracy in America focuses much on American life, Commonwealth deals more with the arrangements of politics in the country. It's long, though — thousands of pages... so you're entering textbook territory by picking up a copy.

If Then, Jill Lepore: Lepore's new book on the birth of "big data" in the 1960s and how it has changed society is another good one. It is especially laudable, in my opinion, as a versatile biography of the people involved in building our current data-driven, sociological future.

Capital and Ideology, Thomas Piketty: I was late to the party reading Piketty's new book, but it is equally as indispensable as his last. More than any year, 2020 proved how our political conflicts are failing to help the people who need government the most.

Empire of Liberty, Gordon Wood: Many of you will know that I studied the early American republic in college, so it will come as no surprise that I thoroughly enjoyed Wood's account of the birth of our nation.

Words that Matter, Leticia Bode et. al: Written by a group of academics, Words that Matter is a great tour of how journalism can shape political behavior. (If you're the type of person who thought James Comey cost Hillary Clinton the election, you'll get a lot out of this book.)

The Upswing, Robert Putnam and Shaylyn Garrett: Like Putnam, I am concerned every day about the fraying of our social fabric, the collective "we" of American democracy. His latest book (in ways similar to Bowling Alone before it) serves as a good data-driven account of how that identity, at least for some of us, was established in the 19th and 20th centuries. I do wish he dealt with the present contamination of communitarian politics by right-wing identity politics, especially in the media, though. This seems to be the chief opponent to the progress he wants. Perhaps another chapter linking the history of progressivism with the current struggle could be appended to an updated version...

How Fascism Works, Jason Stanley: Dismayed by the pseudo-militant politics of identity and exclusion at the Republican National Convention this year, I picked up a few books on fascism to orient myself with the historical context of the present. Stanley's book was as enlightening as it is dismaying.

…

These works are diverse enough that anyone interested in polls, politics, or history should find something that either entertains them or teaches them something new. Bonus points if you can extract both from a single work.

The diversity of the collection might also give you an idea of how scattered my brain is at present. I have found that there is a fine line between reading and thinking widely, and being preoccupied with too many things. I hope the new year can bring more focus. But in the interest of procrastinating even more, go ahead and email me your favorite reads from this year. 😈 You’ll also help me start next year’s book journal off right; I try to read something new every week, then compile the best of them here at year’s end.

Two more things. As this is a stand-in of sorts for Sunday’s weekly post, below you will find a few links to things I read and liked last week. The week’s list is shorter than usual, as it was Christmas and I was trying to avoid my computer, but there are still plenty of goodies.

Finally, here is the subscribers-only post I wrote last week: It's time to ditch polling averages that don't also show uncertainty. If we (forecasters + polling journalists) are trying to give people an idea of how wrong polls could be (and we should be constantly reminding them of this!), the least we could do is actually show them the right levels of uncertainty on our graphs.

Until next time, and Happy Holidays,

Elliott

Weekly links

Where Immigrant Neighborhoods Swung Right in the Election - The New York Times

The Mysterious Link Between COVID-19 and Sleep - The Atlantic

Subscribe!

If you liked this post, you’ll probably like the other ones I write. Sign up now to get them sent directly to your inbox.