Some of the things I learned in 2020 📊 December 20, 2020

Lessons I learned, things I got wrong, and questions we're all still wondering about

Thanks as ever for reading my weekly data-driven newsletter on politics, polling and the news. As always, I invite you to drop me a line (or just respond to this email). Please click/tap the ❤️ under the headline if you like what you’re reading; it’s our little trick to sway Substack’s curation algorithm in our favor. If you want more content, I publish subscribers-only posts once or twice a week.

Dear reader,

We talk a lot about things that are basically constant in politics: individual-level partisanship, ideology, polarization, etc. But focusing on the constant might obscure a proper account of important things that have actually changed. This year seemed to be a particularly radicalizing year for many Republicans, for example, while intra-party fights among Democrats appeared to take on a more age-based gradient than before, with young people (seemingly) getting more liberal, or at least louder.

Accordingly, I want to spend this newsletter thinking through a list of things that we (I) have learned about politics this year. There is both change and continuity, questions both answered and unanswered. My account is neither authoritative nor comprehensive, but it might get us thinking about some interesting topics.

I have a similarly mixed accounting of what I learned personally this year: about work, habits, etc. These are good for my own personal reflection so I have included them for you all to scrutinize.

A quick programming note: I am taking next Sunday, the 27th, off for a short Christmas “vacation.” There will be no traditional weekly post next Sunday. Instead, I’ll be sending out the usual annual list of all the books I read (or, really, the ones I remember reading) this year, with comments where I feel strongly about something. This year’s edition will be particularly poll-focused, for reasons that should be obvious to most.

—Elliott

Some of the things I learned in 2020

Lessons I learned, things I got wrong, and questions we're all still wondering about

Sadly, due to the nature of the lockdowns in Washington, DC, where I live, there are fewer actual memories to recall than I think there was last year. That is a shame, and something I hope we can all remedy after covid-19 vaccinations are widely adopted.

But in the realm of politics and the personal, there is still much to consider. What follows is an unordered, bulleted list of the personal and political lessons that immediately jump to mind when I reflect on the last year.

1. Asymmetric polarization and radicalization are not the same

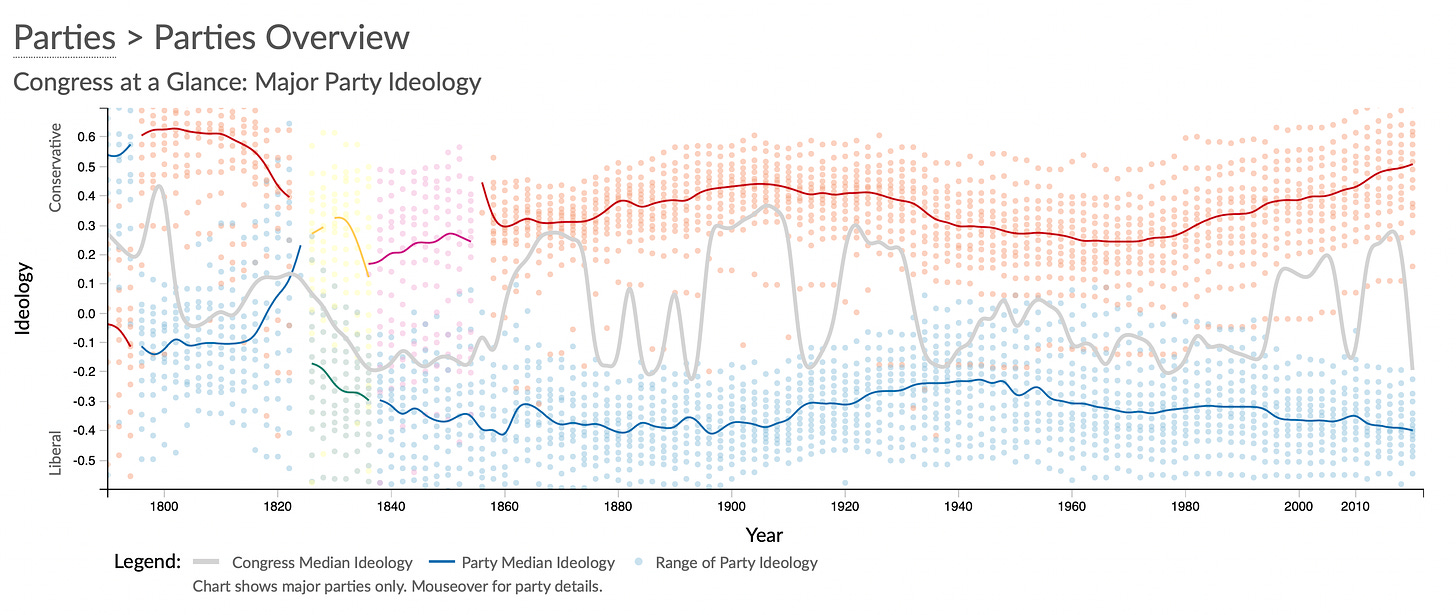

Political scientists and, especially, political journalists, have for a while been wrestling with a contradiction between their work and the real world. For a long time, the patterns of ideological polarization on both the left and right have been asymmetric, with Republican elected officials becoming more ideologically “extreme” than their Democratic colleagues. Here is a chart of the median ideology of House of Representatives members separated by party membership, for example:

There are other asymmetries in ideology too; Republicans rely more on identity-based and symbolic cues for shoring up support, for example, whereas Democrats rely on a lot of traditional politicking and group balancing to keep its members under the same big tent.

However, the asymmetries stop when we begin talking about extra-ideological elements that are present on one side of the aisle and not the other. For example, Republicans have their own ideological, nationalistic news network that is not matched, in viewership or devotion to misinformation, by the left. They are almost exclusively likely to believe “deep state” and QAnon conspiracy theories, and are also the only people trying to kidnap governors or otherwise pursuing partisan violence, often for absolutely and utterly illegitimate reasons. They have been radicalized to question many democratic norms and many right-leaning voters have faltering commitment to democracy in general.

So, I think the better term for these other imbalances is not “asymmetrical,” as Democrats are not also moving to a “polarized” position (they’re not moving at all!), but radicalization, as it better reflects the binary nature of the changes. This is kinda an old take in some circles, but I think this year pretty much proved its validity.

2a. Republicans’ institutional advantages are getting more severe

For a while before the election, it looked like the Republicans’ advantage in the House, Senate and Electoral College would abate somewhat versus 2016/2018. Polls showed Joe Biden had clawed back some support with non-college-educated white voters, who are disproportionately represented in swing states, which would allow him to win the electoral college with a lower margin in the national popular vote.

But that’s not what happened. Instead, Republicans made gains with non-college whites (relative to college-educated ones) and increased their advantage. Democrats would need to win the popular vote for the electoral college by four points — the largest deficit since at least 1976 (when my data start). The GOP accomplished this feat by doubling down on the politics of racial resentment, false consciousness, social/lifestyle warfare, and outrage against (overblown) accusations of far-left radicalism and “socialism.”

2b. This is a feature, not a bug

Of course, this is a feature of the Electoral College. In a party system with factions — which the framers wanted to avoid — the EC confers more power to the party able to win more rural votes, inherently discounting the voices of people who live in cities. With our parties getting more geographically polarized, that partisan advantage has grown more severe.

2c. Any real fix for this seems nearly impossible

The current party system and polarization of reform are major barriers to reform, however. Congress could pass a bill that mandates ranked-choice voting (or another alternative vote method) for Congressional elections, but that would still leave in-tact the partisanship-reinforcing, winner-takes-all Electoral College system that most states use to decide the presidency. Any reforms to the Electoral College would really need to be bipartisan, which itself requires a few democracy-minded members of the GOP gaining power and, in good-faith and to their own electoral detriment, supporting reform efforts to make the country’s voting systems more majoritarian at the Constitutional level.

I really don’t see that happening any time soon.

3. Polling isn’t broken, but partisan non-response is real and happens across modes

Pre-election polls in the 2016 election underestimated Hillary Clinton in key swing states, in part because they didn’t sample enough Republican voters and in part because they were conducted too soon before the election. Pollsters thought they could fix this issue by adding more weights for educational attainment, polling later in the election cycle (to catch last-minute deciders), and conducting more high-quality polls at the state level. Evidently, they were wrong. This year, the same patterns of error happened, but by a greater magnitude.

Pollsters evidently have a problem getting Republican voters to answer their polls. Some analysts have theorized that this was particularly true this year when more Democrats were staying home due to partisan cues over covid-19 lockdowns, but the baseline finding is nevertheless correct; the bias is at least as bad as 2016 no matter how you slice it, and maybe worse.

Before the election, I (and co-authors) had theorized that one way our polling aggregation models could control for this bias would be to adjust for the residual between the average of polls that didn’t weight by partisanship or past vote and the average of those that did. Evidently, such a correction did not work, as the forecast that I built with Andrew Gelman and Merlin Heidemanns only barely outperformed the competition. So there’s something different even with the types of Republicans who are answering polls that is making them more Democratic-leaning — and we don’t know how to precisely account for than beforehand.

It will take a while for pollsters to sort that out. The good news is that they probably can, through a mix of new technologies for pre/post-processing, and good old-fashioned hard work.

4. Demographic voting patterns are less sticky than I thought

Before the election, I tweeted a very wrong statement that Trump’s margin with Hispanics only looked better than in 2016 because a lot of Biden voters were picking the “not sure” option in the polls, but would come home. That was wrong. What it taught me is that we should be using a slightly more elastic prior when thinking about group-level voting habits. (That being said, the magnitude of the pro-GOP shift among Hispanics and Latinos is quite a bit bigger than most single-cycle shifts, so it would have been hard to call it exactly right either way.)

5. I was also wrong about potential covid-induced polling error (but right about polarization)

Many of you will remember the highly public and tense discussion between me and Nate Silver over the summer. Well, there are ways to test the various hypotheses we made, namely by using election results.

First, it appears I was right to assert that polarization makes politics less volatile, so we can be more confident about election-day predictions made in, say, March than we could have been in 1950. However, I was wrong to overlook Nate’s point that covid-19 could introduce more error in the polls that we couldn’t account for via an economic proxy. (I still think that just adding 30% extra uncertainty ad-hoc was the wrong way to go about this, though.)

For more, read this blog post.

6. I know less than I thought I did about the role of public opinion in democratic theory (and learning more has been great)

In the course of my thousands of pages of reading for book research, I have learned many things. They can mostly be grouped under a single graph, where y represents what I think I know about polls and democracy and x is what I actually know, with a squiggly line representing the Dunning-Kruger curve. I have of course predictably proceeded along this curve — I knew like 90% as much as I thought I did after graduating college, and that gap is more like 50% (I guess?) now — but the y-intercept is higher than I thought. There’s just so much to learn.

Relatedly, one of the joys of book-writing has been all that I have learned in covering the various subjects of the narrative. On political theory, John Dewey, Jeremy Bentham, Thomas Booth, Lindsay Rogers, and others present intriguing questions I had not considered before. On polls, the developments in methods over the past thirty years are also more substantial than most journalists have covered so far. It’s really exciting to internalize this knowledge and put it all down on paper.

…

Some personal stuff now. Namely: How do we value work?

This is something I’m still thinking about. When I was 16, I wrote an essay and made a video log about the transcendentalists and their influence over democracy. (Thank god I have erased all the hard drives that vlog was ever on.) We can’t all go live in a forest and write work that is beautifully connected to nature, but my mind often wonders about the true (ie human) value of the work I do, from political data journalism to commentary about politics and polling. I have a few considerations: First, I guess we all want to add value to humanity, right? Or maybe, when we’re young, we just dream above our stations in life. Finally: maybe I just like to be around trees. My mom often tells a story about how, when in the NICU as a baby, I would only go to sleep in a bed by the window, overlooking the green space outside. We can make something obnoxiously poetic about that, I’m sure...

Relatedly: Through the latter part of this year, faced with the pressures of constant election model coverage and the daunting word-count-deficit of my book, I have been preoccupied with strategies for working better and smarter. What are my best hours? 9 PM - 1 AM, it seems. Does exercising help me focus? Yes, but it’s hard to do during the pandemic. Can I focus better if I drink a lot of water before having coffee? The jury’s still out! Etc. Perhaps the bottom line is that I often don’t feel connected to my work, and in our world of constant distractions that loose connection can easily be temporarily severed by an email app, tweet, Netflix binge, etc. If productivity is something you’re interested in, I’ve heard that Charles Duhigg’s Smarter Faster Better is a good book but I have not yet read it myself.

…

Overall, I was pleased with the work I did, the things I learned, the connections I made, and the progress I completed toward various personal and professional goals this year. 2020 was a fruitful year for me. Of course, I know how lucky I am to be able to say that. I hope my letter at this time next year will be more positive.

Posts for subscribers

December 18: Giving people money is (surprise!) really popular right now. 86% of voters want Congress to approve an extra round of stimulus spending

A reminder: it’s that time of year again! 🎄 The holiday season typically produces a big chunk (think 20%) of my yearly subscription numbers, both for premium editions and the weekly update. I would be grateful if you would consider sharing the link to this newsletter on social media, or signing up for extra posts yourself if you haven’t already. As per my normal holiday rate, new subscriptions made before January 1st, 2021 will be half-off or the entirety of the next year. Perfect for a subscription for yourself or a gift to a close friend.

What I'm Reading and Working On

I picked up a copy of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass yesterday. It was missing from my growing collection of classics, which I sadly neglected to build out until recently. Of course, I picked Whitman because his writing on democracy is also directly relevant to my work, so you couldn’t really call this reading classics for classic’s sake… but…

In related news, earlier today I typed the 30,000th word for my book, which means I’m officially halfway to a first draft! Of course, with revisions and edits, there is a lot more work to be done. But I’m patting myself on the back for the progress I’ve made so far.

Other links and recommendations:

Thomas Edsall for the New York Times: Opinion | America, We Have a Problem - The New York Times

Jamelle Bouie also for the Times: Opinion | It Took Mitch McConnell Six Weeks - The New York Times

This painfully relatable tweet from Christopher Ingraham, a data reporter for WaPo

This wonderfully expository piece about Reconstruction from my colleague Jon Fasman, published in The Economist’s Chrismas issue: Reconstruction - Reconstruction reshaped America along lines contested today | Christmas Specials | The Economist

Thanks for reading!

Thanks for reading. I’ll be back in your inbox next Sunday. In the meantime, follow me online or reach out via email if you’d like to engage. I’d love to hear from you. If you want more content, I publish subscribers-only posts once or twice each week.

Pet photo contest

Here is a holiday photo of my cat, Bacon. Merry Christmas to all who celebrate! See you again after the holidays.

For next week’s contest, send me a photo of your pet(s) to elliott[AT]gelliottmorris[DOT]com!

That polarization graphic is pretty crazy! Look where we are now and we were in 1860. Maybe 1860 isn't something we should compare today to, the circumstances are pretty different and unique back then, but the present day ideological gap is very large.

A four point Electoral College advantage for Republicans is ridiculously unfair.

Merry Christmas and have a safe holiday!

-Elliot