Links for March 5-11, 2023 | Regulating drug prices; Rating pollsters; And what campaign lawn signs tell us

Hmmm... this sample is convenient.... tooo convenient

Happy Saturday, all

This is my weekly post for paid subscribers discussing recent uses of (mostly political) data that I think are interesting and worth discussing. Comments are welcome below — and if you enjoy this, please share it with a friend!

1. Regulating drug prices: so hot right now!

A new poll from The Economist and YouGov last week found overwhelming support for the government negotiating drug prices with insurance companies. Specifically, when asked “Would you support or oppose the federal government and private insurance companies negotiating with prescription drug manufacturers to set universal prices for prescription drugs?” 62% of Americans said the somewhat or strongly support the policy, whereas 19% opposed it.

This includes a majority of Republicans, independents, conservatives, moderates and (somewhat obviously) Democrats and liberals, too. Even a majority of Trump supporters said they would support the federal government negotiating the prices of prescription drugs!

Support was somewhat higher when respondents were asked about negotiating prices specifically for Medicare recipients (66% support; 14% oppose) and for the prices of insulin (72% support) and cancer drugs (73%).

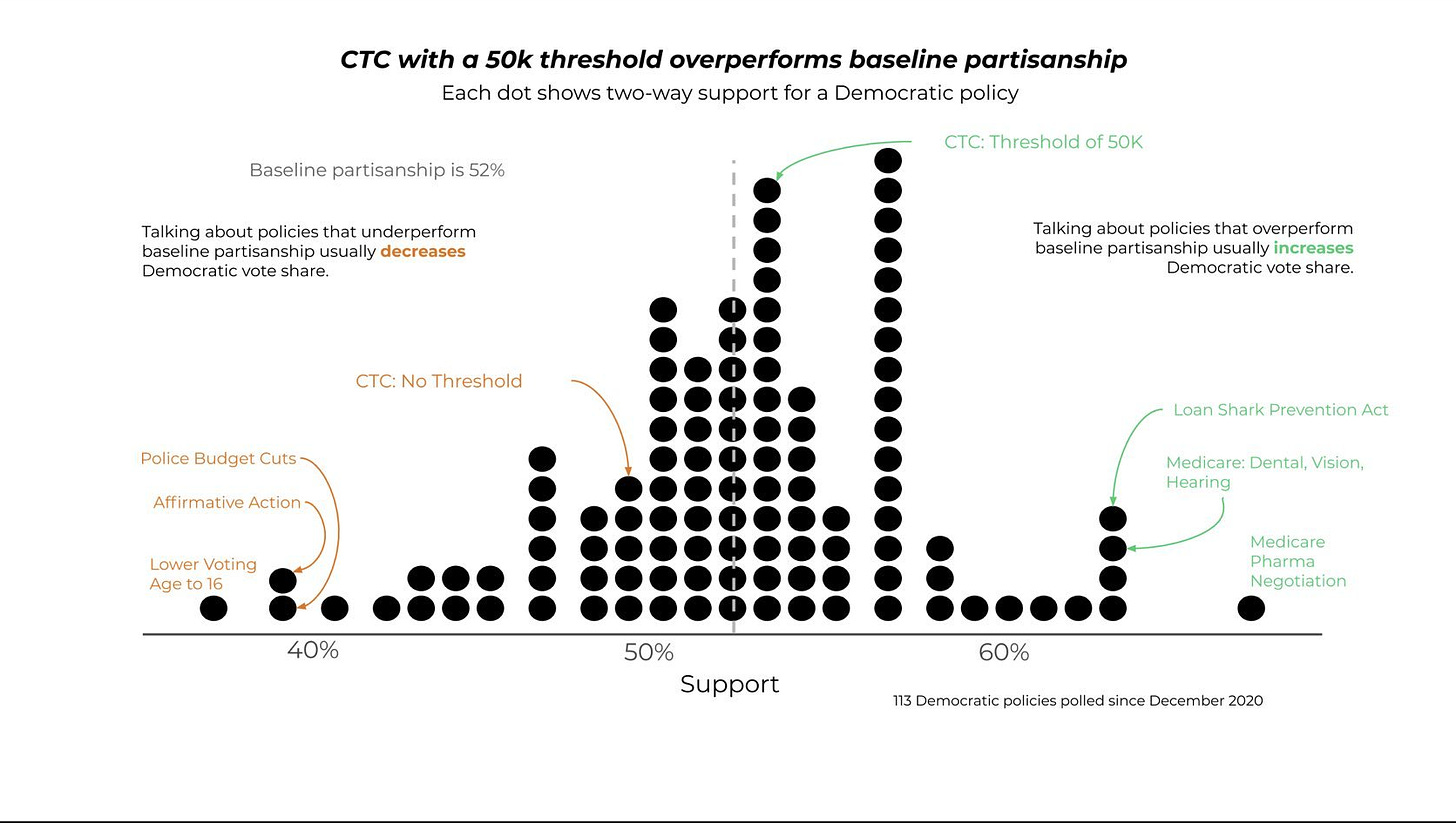

This would be a very popular policy to run on. It is one of the most popular proposals in America today; more popular even than expanding Medicare to cover dental, vision and hearing or preventing interest rates for personal loans from exceeding 15% (graph credit).

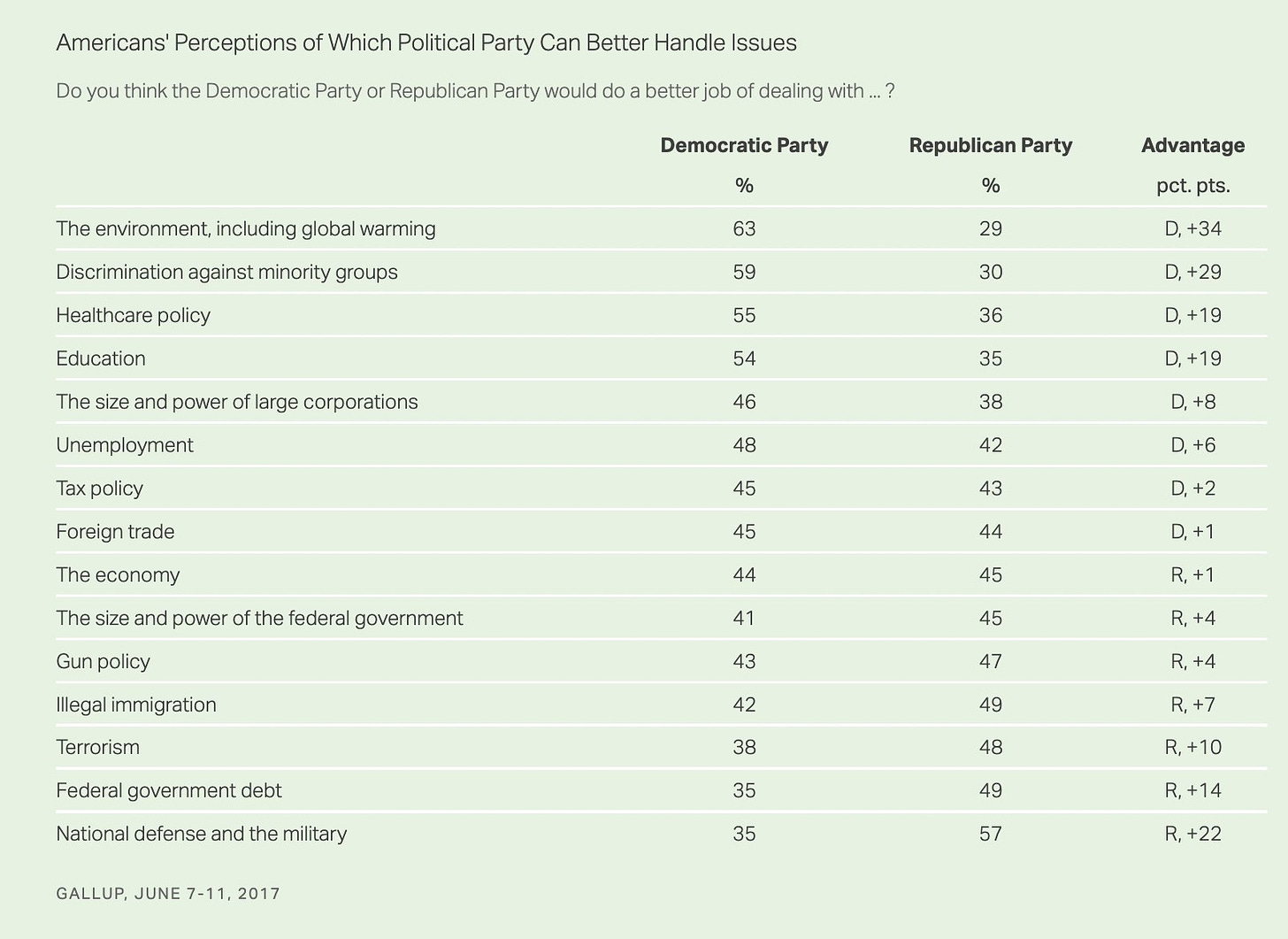

And don’t forget that health care is one of the Democrats’ strongest issues. A 2017 Gallup poll found that 55% of adults say the Democratic Party “would do a better job of dealing with health care policy” than the Republican Party.

If Joe Biden is looking for a popular issue with cross-pressured voters, government drug-price negotiation would be a good one. (Also, it’s a good policy that would help a lot of people!)

2. 538’s new pollster ratings: NYT boosted, Trafalgar falls

FiveThirtyEight has long published quantitative ratings for each pollster in America—one of its more novel inventions and something that has (in the past) made its averages more accurate than the competition. You may be familiar with the letter grades they assign to each firm—Ann Selzer’s Iowa Poll gets an A+, for example, while an online outlet called Momentiv (formerly SurveyMonkey) gets a C.

I have pregrades detailed several disagreements with how the formulas powering these ratings work. The summry critique is that 538 grade’s pollsters on their accuracy, which is a useful metric of how a single firm does on average, but does not grade firms based on their bias, which is a much more important metric to pay attention to when you’re aggregating polls from different firms.

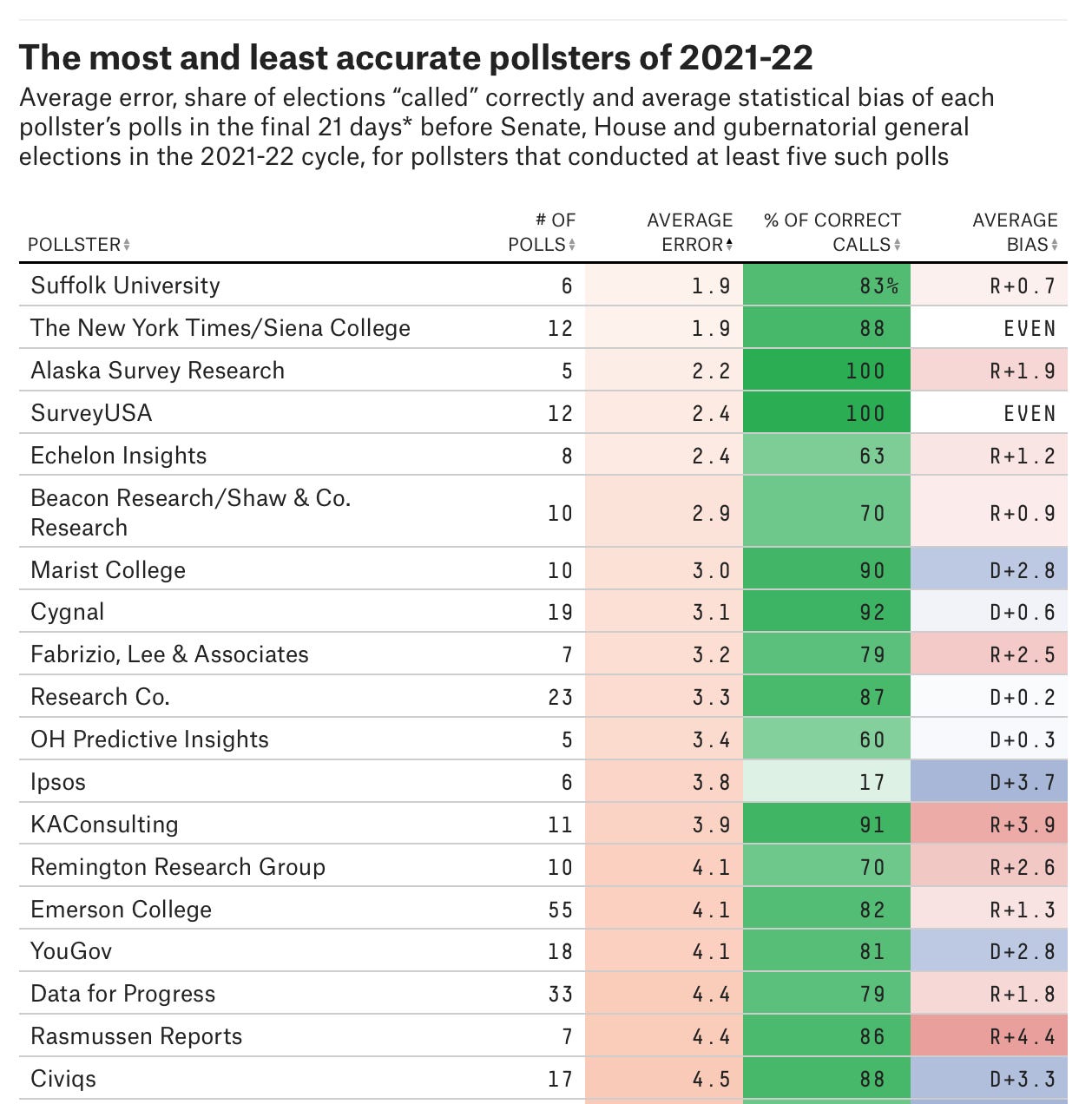

But putting those caveats aside, let’s look at the big winners and losers according to their formula. Here is the 538 table sorted by each firm’s average error last cycle:

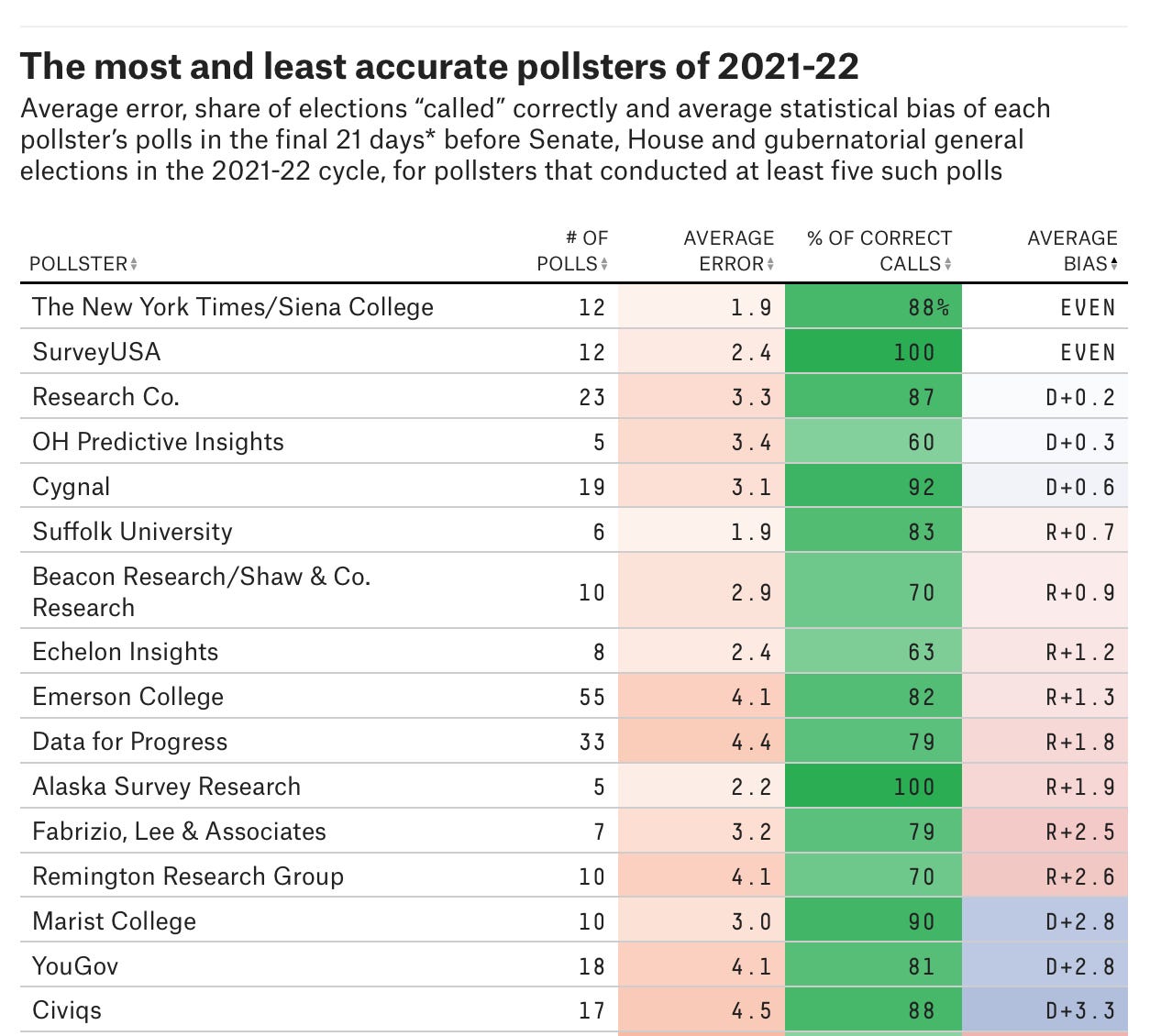

And here is the same table sorted by each firm’s average bias:

Congratulations are in order for Nate Cohn and everyone doing the polls for The New York Times Upshot/Siena College last year. They are now officially the best pollster in America, per 538. Their performance shows how investing heavily in both the design and modeling stages of a poll can pay off. Though, frankly, they also had a (relatively) easy year with signs of little differential partisan nonresponse in most polls.

Now on to the big loser: Trafalgar Group, which conducted 37 polls and had an average error and bias of 5 points toward Republicans in the 2022 cycle. That has cost them dearly, moving from an A- to a B rating in FiveThirtyEight’s dataset.

In reality, that rating is likely still too high. Again, because FiveThirtyEight premiums accuracy over bias, pollsters like Trafalgar with moderate to severe amounts of predictable right-leaning bias can significantthe rating systems if they get lucky and all other pollsters have either large errors or reliable biases pointing even larger in the opposite direction. It was easy to see that Trafalgar had gotten “lucky” in 2016 and 2020 by putting their thumb on the scale and that one day they would run out of luck (see link from me and link from Andrew Gelman). But 538’s algorithms don’t take this into account. It’s likely that if the industry has another good year on average they will continue to slide towards the C or D rating they likely deserve.

3. Empirical evidence for why you shouldn’t ever look at political lawn signs

“I’d go to these rallies and people would say, ‘We’ve never seen this,’” Doug Mastriano, the losing Republican candidate in last year’s Pennsylvania Senate race, said in a recent interview with Politico’s Holly Otterbein. “In Josh Shapiro’s home county the night before the election, I had over 1,000 people — we stopped counting at 1,000. I saw no Shapiro signs in his own county. Here I am in Montgomery County the night before the election, I’m like, we got this. The rally was just electric.”

But, opines the Washington Post’s Philip Bump, “Mastriano did not ‘got this.’”

His error was an age-old one: trusting that what you observe around you is representative of reality in places you don’t observe. Mastriano allegedly believed he would win despite very bad polling because he was seeing so many lawn signs in support of his candidacy. But lawn signs don’t vote.

The statistical critique here is two-fold. First, lawn signs constitute what we call a “convenience" sample”: that is, a sample of a larger population that is assembled of observations that are easy (or “convenient”) to gather. So one problem is that the lawn signs any one of us sees don’t represent all the lawn signs in the country/state/district/what-have-you.

The bigger problem is that there is differential demographic and partisan non-response in who chooses to put out a lawn sign for their candidate. Maybe one side is more enthusiastic about their candidate; maybe their local office went door to door handing out these signs. Maybe one particularly enthusiastic neighbor did the canvassing. I could go on. The point is that individuals self-select into the process of putting up a sign for their candidate in their yard, and that selection process yeilds an unrepresentative portrait of reality.

Or, as Bump puts it:

If your metric for measuring your opponent’s support is lawn-sign visibility — since candidates in particular are unlikely to hear from supporters of their opponents — the relative density of voters is important. We know that sparsely populated, rural areas vote (much) more heavily Republican. Those large, open areas are therefore presumably more likely to be peppered with lawn signs for Republican candidates. Get into more densely populated areas and that might change, but only in a relatively small (albeit more vote-heavy) area.

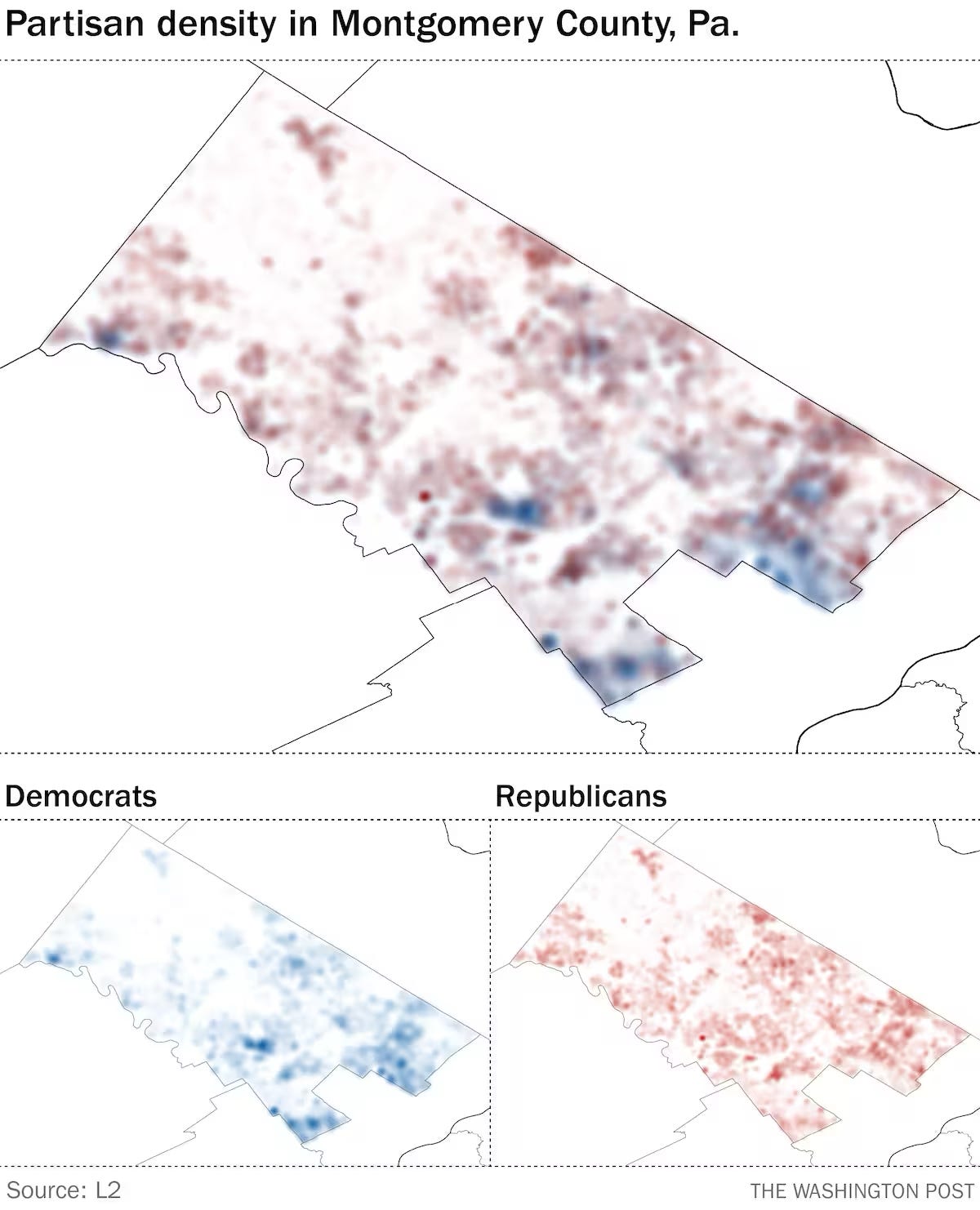

Using voter data from L2, a political data firm, we plotted where Republicans and Democrats live in Montgomery County, the place to which Mastriano was referring. You can see that density of blue/Democratic voters doesn’t overlap neatly with red/Republican ones. If you spend more time in or driving through those redder areas than in denser neighborhoods, you’ll see more Mastriano and fewer Shapiro signs.

And they include this chart:

I think that’s pretty cool. Here’s my suggestion to Bump: write an algorithm that (a) randomly assigns voters into the pool of people who put up lawn signs for their party and then (b) randomly drops a “person” in any neighborhood in Pennsylvania. Count up the lawn signs around them in a one-block radius, and report how often the tally is not predictive of the actual partisan breakdown of Pennsylvanians. That might not really tell us much, but I imagine that would be a fun program to write.

Just like this piece was a fun new take on age-old advice: Don’t try to predict election results by counting up lawn signs. (Or by counting crowd size, for that matter.)

That’s it for this week’s top links. Thanks for reading and being a member of the community supporting this newsletter. Consider sending a free trial to a friend you think will enjoy the subscriber-only content.

Have something interesting for me to write about? Send it to me on Twitter or via email (I’m gelliottmorris@substack.com).

Have a great week,

Elliott