Is covid-19 dragging down Joe Biden’s approval rating, or helping it? | No. 169 — November 7, 2021

Voters give the president and his party even poorer marks on other salient issues, such as the economy, public spending, and immigration

The time change and early nightfall this Sunday have reminded me that we will soon be entering our second winter with the threat of covid-19 hanging over America. The winter itself is not so significant in this regard, save for the assumption that spending more time indoors will increase circulation of the coronavirus among those who have yet to be vaccinated for or infected by it. That’s a lot of people, to be sure — roughly one in every six or seven adults, if my back-of-the-envelope math is right.

No; instead, the dropping of leaves and premature dusk have prompted me to recall just how long the pandemic has been at the forefront of American politics. We have been fighting covid-19 for 20 months now — nearly 90 weeks when news of the virus has consumed our collective attention and burdened our national psyche. The virus has caused the premature deaths of some 750,000 Americans, according to official tallies. The true cost may be closer to one million, according to The Economist’s modeling of so-called “excess deaths.” And while we are well below the most recent crest in new daily cases, we are well above the levels from early this past summer or early fall 2020 — when hospitalizations were low and a return to “normal” seemed imminent.

Such trauma tends to take a toll on a nation. That’s true for us personally, but also politically. Crises historically cause a brief “rally around the flag” effect that sees approval ratings rise for incumbents, but leaders then lose ground as troubles persist.

Accordingly, many political journalists and commentators have theorized that Joe Biden’s approval ratings (currently sagging at around 43%) would be higher if not for the relatively high number of new cases and deaths (“relative” because the toll is as high as last March’s even though vaccinations are higher) and the continued visual presence of covid-19 in our daily lives — eg from mask mandates, business closures, and labor shortages, just to name a few. Some political handicappers have even reckoned that the Democrats’ recent loss in Virginia, where the former governor Terry McAuliffe was defeated by Republican Glenn Youngkin by just 2 points last Tuesday, would not have happened were it not for covid-19.

However, to my eye, these theories are refuted by the evidence. For one thing, Joe Biden’s ratings have stayed low despite a recent pronounced decline in the number of new covid-19 cases per day. You can see that in the following chart from 538, which shows the number of new cases over time in the top panel and Biden’s job approval (specifically on covid-19) in the bottom panel. Note that the two don’t tend to move together; Although a rise in covid-19 cases in the summer corresponded with rising net disapproval ratings for Biden, a decline in the number of new cases this fall has not produced a better approval rating.

This suggests that tackling the coronavirus is not likely to solve the president’s problems, as many politicos suggest. Certainly, people might reward Biden a little for an outright “end” to covid-19, but the data don’t support the argument that the issue is a significant drag on his popularity. It’s also possible that people have been exposed to enough events and information on covid to form lasting opinions of how the president has handled the issue. If that’s true, despite how covid-19 cases trend in the future, aggregate opinions would change very little.

Now, let me take this one step further. Although the conventional wisdom is that covid-19 is dragging Biden down, and we have so far established that that doesn’t look true, I think it’s actually possible that the virus might be propping him up — to an extent. The errors of the conventional wisdom here are two-fold, in my view: First, from underestimating the president’s approval on covid-19; and second, from focusing too much on the potential effects of the coronavirus and ignoring the salience and political valence of other issues.

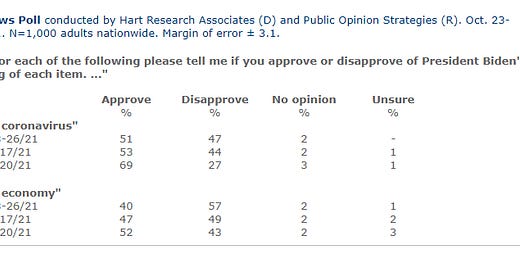

A number of recent polls have shown Biden’s approval rating on covid-19 is better than his rating for other issues. For example, take an NBC News poll released late last month. It found Biden’s net approval on covid-19 was +4 points, whereas his approval on the economy was -17. The polls also show that economic evaluations have taken a sharp dive over the past month.

A recent national Quinnipiac University poll also showed similar numbers, with Biden at -2 on the coronavirus, -16 on the economy, -24 on foreign policy, and -42(!) on immigration:

As if that weren’t bad enough for Democrats, the NBC poll also shows broad issue ownership for the Republican Party on the economy and government spending — the two issues that, aside from the coronavirus, have dominated the news over the past couple of months:

. . .

This all raises an obvious counterfactual. What would Biden’s approval be like without covid-19? We can only speculate, but based on this evidence, I think we can make a strong case that it would be worse. Media attention and public pressure on other issues where the president is less popular would likely drag down his aggregate ratings. Certainly, it looks like an end to the pandemic will not save his presidency.

Posts for subscribers

If you liked this post, please share it — and consider a paid subscription to read additional in-depth posts from me. Subscribers received two extra exclusive posts over the last week, including:

One post on the exit polls from the Virginia race and why I don’t trust them:

And another on why Democrats lost and what they can (and can’t) do about it:

Links to what I’m reading and writing

Not a lot going on re: the reading front this week (you’ll see why in a second) but I do want to recommend one item to you all. Nick Offerman, the well-known actor/comedian and woodworker, has a new book out titled Where the Deer and the Antelope Play. It’s about the physical beauty of the United States and our endangering relationship with nature, and ourselves. While it’s not exactly a new book — in the sense that the majesty of the American landscape is an old and well-trodden subject, and Offerman’s commentary and prose on these subjects occasionally summon exaggerated and prolonged eye-rolls — I did find his packaging of musings on the topic and the characters he pokes and prods to be well worth the pages. It was an enjoyable read, which is more than I can say for many of the texts in my office.

On writing: It was another full week for me at The Economist. I wrote three articles, all of them related somehow or another to Tuesday’s elections. One analyzed the results from Virginia last Tuesday night; another put the results for gubernatorial contests and ballot initiatives across several states in the broader context of thermostatic opinion and dug into both the national and local/parochial causes of Democrats’ losses; and a final column for the paper’s US politics newsletter addressed the historical pattern of the results in Virginia’s governors’ races to be a strong predictor of what happens in subsequent midterms elections.

Now that Congress has passed the bipartisan infrastructure bill (er, “framework”), I’ll likely be publishing some new work next week that explores whether the 2009 stimulus program helped Democrats in 2010 and hypothesizes about some of the political effects of Biden’s various big-spending programs.

Thanks for reading

That’s it for this week. Thanks so much for reading. If you have any feedback, you can reach me at this address (or respond directly to this email if you’re reading in your inbox). I love to talk with readers and am very responsive to your messages.