Give public opinion a chance 📊 February 21, 2021

Trusting the people is hard right now, but we shouldn't abandon our democratic values because of polarization and misinformation

A note: Thanks as ever for reading my weekly data-driven newsletter on politics, polling, and democracy. As always, I invite you to drop me a line or leave a comment below with your thoughts. Please click/tap the ❤️ under the headline if you like what you’re reading; it’s our little trick to sway Substack’s curation algorithm in our favor. If you want more content, I publish subscribers-only posts roughly twice a week.

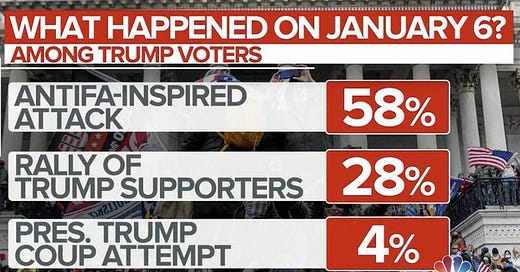

This morning, NBC News ran the following graphic of poll from USA Today showing that the majority of people who voted for Donald Trump in 2020 thought that the January 6 assault on the US Capitol was an “Antifa-inspired attack,” rather than a mob of the then-presidents supporters who wanted to overturn the (verified) results of the election in order to “take back [their] country.”

I have written a lot already about that day already — among the articles: why it was a predictable consequence of radicalization and how it reveals the extent of illiberalism among mass and elite Republican ideology — but want to add some thoughts about trust in the public will. The setup is: if 25-30% of the country refuses to believe verified facts, how can we trust the people to inform government policy like democratic theory says we’re supposed to?

As I have been finishing my book and catching up with the present-day — remember, it’s part history, so spent most of the past 4 months thinking about the past — I have been thinking a lot about this question. The full answer to the question of “can you trust the people?” is too long for one letter, but if we narrow the question, we may learn something. The question as I’ve revised it now asks: Can we trust “public opinion” if one part of the public has been duped into believing lies?

At first, the answer is a simple “yes.” After all, the vast majority of Americans — rather than the more conspiratorial subset of people that the grouping “Trump voters” offers us — still see January 6th for what it actually was. And in a democracy, the majority rules.1

However, the better answer is (per usual) more complicated. A fair account of the subject needs to reckon with the argument that a fourth of Americans aren't adding to the wisdom of the public if they aren't getting the requisite information to rationalize or otherwise deliberate about what government should do. For deliberation to work we must have information about all sides of an issue and then reach a conclusion. That the right-wing information ecosystem has successfully pushed The Big Lie onto its tens of millions of followers (both sitting and unwitting) violates this core assumption of our democratic process.

Of course, you don’t need to be well educated to deliberate. The constitutional theorist and proponent of public opinion James Bryce, as well as the pollster George Gallup who inherited many of his ideals, argued that the common person could also contribute their experiences, feelings, and gut instincts about government to our conversation about policy. We need not always obtain college degrees to know when a policy tradeoff is against the community’s interests. However, a minimum requirement of worthwhile gut opinion is that it’s not merely a reflection of by propaganda or misinformation. The idea that our gut reactions are valuable only holds true if, in our gut, we have virtuous, community-driven values.

So, as long as you're being true to voter psychology and the way we adopt information and attitudes from our leaders, you encounter a tough paradox when arguing in favor of a more poll-informed, democratic society. You also have to argue for good leadership, which means acknowledging the public can be wrong sometimes through no fault of its own. Political polarization, media echo chambers, and misinformation have made us susceptible to attitudes that steer the public option away from the general interest of the community.

I see this as a problem that most pollsters who thought about democratic theory a half-century ago didn't — maybe even couldn’t — consider. Gallup was arguing for a national New England Town Hall in a time when the two parties had essentially agreed to disenfranchise black voters from the political system, focusing instead on “bread-and-butter” issues and foreign policy where information and debate were commonly disseminated through the media. There was no Fox News and no algorithmic news feed. I imagine he would have been averse to this argument — essentially, that sometimes we can’t trust the people — but it’s easy in hindsight to see that his lack of information was leading him astray.

The easy way to resolve this is to say that good, democratic governance also relies on good-faith leadership from political elites, opinion leaders, and the information class — which… duh! But this is a wrinkle in the debate over public opinion that is too often polarized between “trust the public all the time” and “never trust the public.” The reality is a little more complex — tougher, but also more satisfying.

The final thing to note is that the several contemporaneous problems with trusting public opinion without context or leadership aren’t inherent to the wisdom of the crowd itself. We cannot blame the public for being misled by self-interest media moguls and politicians who are misleading them to gain power, just like it is not entirely the public’s fault that they have not received the information that elites and theorists might want them to have before deliberating public policy. If we want the people to be better decision-makers, we can help each other realize that eventuality. The flaws in public opinion, in other words, are not really in the public, but the institutions and actors that influence it. Polarization and misinformation are challenges — mere caveats — to trusting the public, not reasons to condemn it.

Posts for subscribers

February 19: The future of public opinion polling. After a few bad years, it’s clear that polls have a lot to improve on — but they are still far better off than most critics allege

What I Wrote

My Friday column for The Economist’s Checks and Balance newsletter was about a decline in skepticism of the covid-19 vaccine, and reassuring stability in partisan willingness to get jabbed. I also wrote about mass polarization over presidential job approval hitting an all-time high.

Book progress is still hovering at around the 85-90% mark; I have written a lot but also done a lot of editing (Hemingway says the best writing is rewriting; he also wrote drunk) that keeps knocking me back from my ultimate word target, and I added an epilogue on polarization and misinformation that will take a while to polish.

What I’m Reading

On Tuesday, I picked up a copy of Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste, a brilliant book about race and power in American society.

The Economist on decarbonizing power production to avoid future catastrophes like the one we saw in Texas this week

Derek Thompson for The Atlantic on covid-19 cases dipping quicker than expected

James Parker, also for The Atlantic, giving us an ode to naps

A new Gallup poll found that 62 percent of Americans believe that America needs a third major party, the highest level of support since 2003. (Be wary of any implications, however, as third parties don’t usually work out in plurality electoral systems — especially ones with electoral colleges!)

Feedback

Thanks for reading today. If you have any feedback, please send it to me at this address — or just respond directly to this email. I’d love to hear from you. If you want more content you can sign up for subscribers-only posts below. In the meantime, follow me on Twitter for related musings.

This is not quite as true in America, given that our geographic-based systems of representation often enshrine minority rule