Did the CDC's revised masking guidelines in May cause the current spike in covid-19 cases? 📊 July 18, 2021

Blaming government decision-makers is easy, but actually changing individuals' behavior is hard — and predicting covid spikes even harder

This is my weekly data-driven newsletter on politics, polling, and democracy — and whatever else I’m thinking about. If you want more frequent posts on these subjects please sign up for a paid subscription. I send out subscribers-only posts twice each week.

On Saturday, Leana Wen, a visiting Professor at the George Washington School of Public Health and a contributing columnist for The Washington Post and CNN, sent a tweet writing that “38 states have a greater than 50% increase in #covid19 infections.” Wen argued that “This can be traced back to the CDC’s actions that essentially ended mask mandates for the unvaccinated. The ‘honor system’ did not work, and instead disincentivized people from getting vaccinated.” According to Wen, the CDC’s announcement in early May that vaccinated people could take off their masks indoors led to “widespread chaos and confusion” followed by a “precipitous and premature” decline in mask mandated and mask-wearing. This then led to unvaccinated people spreading covid and causing a spike in cases.

This sounds like a sensible argument at first, but it gets a few important things wrong about (i) the covid timeline, (ii) how and which people have tended to respond to government public health instructions, and (iii) pre-existing trends in masking habits that I think we can all learn from.

To take those in reverse order: Let’s look at some data on masking habits around the time the CDC changed its rules last May. We will set aside for now whether the decision changed official government mask mandates, because what we really care about is whether masking behavior changed. We want to identify the dependent variable, not just a proxy for it. Here is a tweet I sent a few days after the CDC changed its masking recommendations:

According to polling data from YouGov, the announcement did not have any clear immediate impact on public masking trends. Instead, after breaking down masking habits by vaccination status, what really pops out is that vaccine-reluctant people were already unlikely to say they were wearing a mask all or most of the time. They were violating public health guidelines long before the CDC changed them.

That finding doesn’t change if you increase the time horizon. YouGov has a graph on their website of the share of people in each of a few dozen countries that say they are wearing a face mask in public places. If you match up the US data with the rough date of the CDC rule change and run flatter through their numbers, it’s clear that the announcement didn’t cause a sharp break in habits. There look to be three trends: a roughly flat one from January to March, a sharper one from March to early June, and an even steeper decrease in masking from June 1st to today.

Here are two quick robustness checks: First, you can see that the US trend really broke away from the Germany and UK trends in June, not mid-March. And second, there was a similar non-break in the share of people social distancing around the rules change:

From these data, we would reject the hypothesis that the CDC announcement made Americans drop their masks, increasing their vulnerability to covid. Instead, unvaccinated people continued to get less careful in a predictive pattern. And this makes sense! YouGov’s data from around the time of the rules change showed that only a quarter of the people most opposed to vaccinations and masking said they trusted the CDC “somewhat” or “a lot”, while 48% said they didn’t trust it. For elites and institutions to drive opinion change, they must have a population willing to listen to their messaging. In this case, the most vulnerable Americans weren’t responsive to the messenger.

. . .

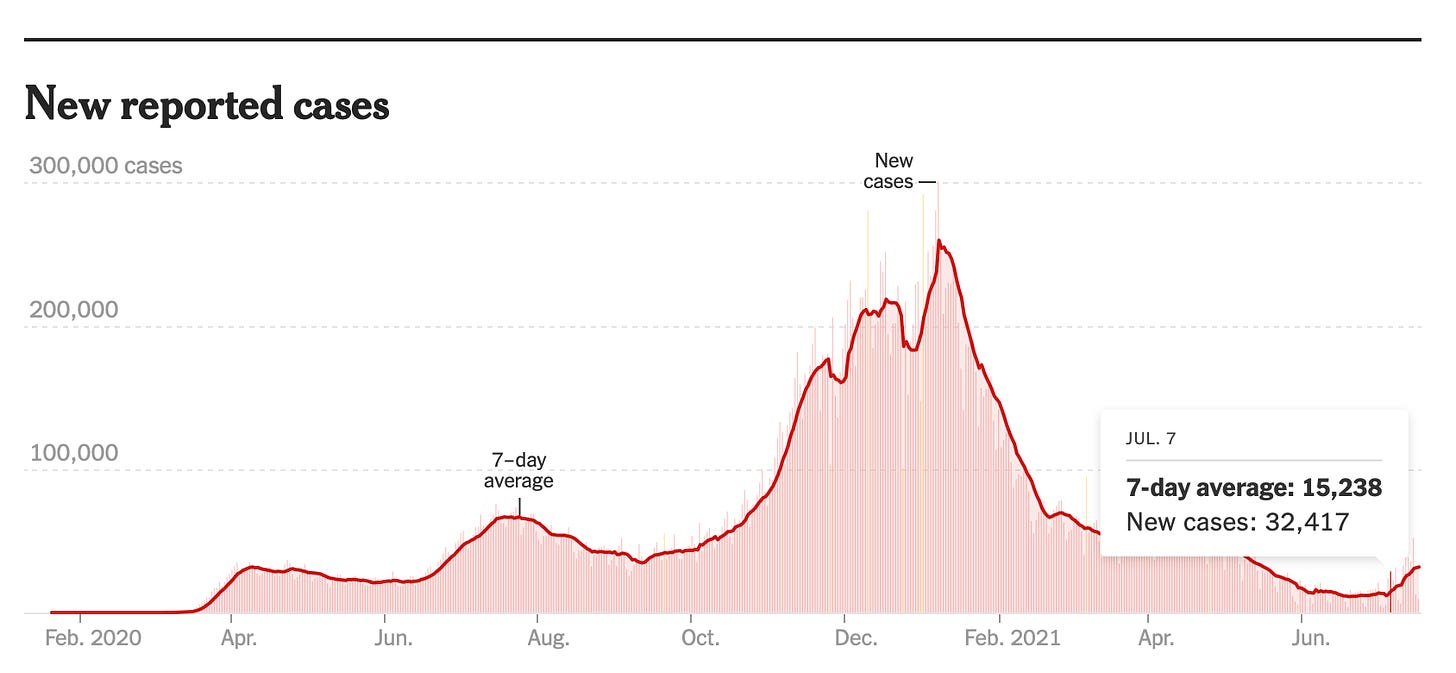

Let’s forget the above evidence for a moment and focus just on case numbers. I went to the New York Times’s website and tried to eye-ball the inflection point of the fourth covid wave nationwide. The day the number of newly reported cases in America started increasing was around July 7th. The people showing up in the hospital or reporting cases to authorities then would have been infected around two weeks prior, given what we know about the lag between contracting the disease and showing symptoms. That would have been the third week of June — a month after the CDC changed its rules on masking. Based on this alone, Wen’s theory just doesn’t hold up.

. . .

The overall lessons from these data are three-fold. Let’s review. First, the inflection point (July 7) in the fourth wave doesn’t even match the date of CDC rule change with a two-week lag (May 31st). Not even close. Second, that the people who are driving the current increase in cases — vaccine-hesitant or -reluctant Americans — were unlikely to mask from the get-go, and had already begun throwing out their masks before it changed its rules. And third, that those people were unlikely to take their cues from the CDC anyways.

The best guess is that the current spike in cases can be traced back to events or epidemiological evolutions that happened in the latter half of June. That is, of course, about the time Delta variant started circulating in earnest across the country. The best case in Dr Wen’s favor is that the CDC’s new masking guidelines in March set the stage for bars and restaurants to re-open around the time the virus was getting more contagious. But even that is not as unambiguous as she first made things seem.

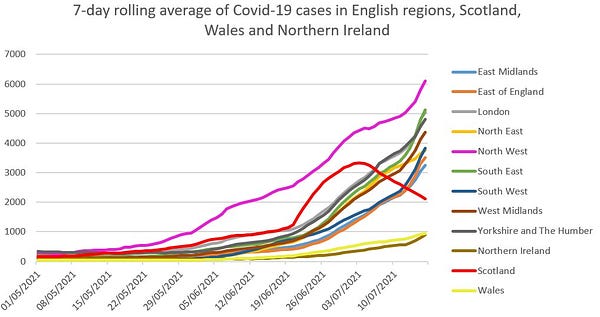

UPDATED July 19, 1:51 ET: I ran across this tweet of covid cases in Britain this morning. Perhaps the best evidence that the CDC mask rules are not the cause of the current covid spike is that there is a parallel surge happening in the UK today. Residents there, of course, would not have followed the lead of the American scientific community. But they would have been impacted by the Delta variant at around the same time as us.

Posts for subscribers

July 16: Two-thirds of southern Republicans want their states to secede from the union. Democratic support for constitutional "hardball" is a signal of broader democratic distress

Links to what I’m reading and writing

The book goes to the copy editor tomorrow. Hooray!

We (meaning people who also work for my employer) have a new polling average for the upcoming German federal election online at Economist.com:

Here is a piece from me on how Cuban Americans feel about policy towards the island, and how that might help or hurt Joe Biden.

And for more debunking of popular covid and electorate myths, check out this thread.

Thanks for subscribing. Got leads?

That’s it for this week. Thanks so much for reading. If you have any feedback, please send it to me at this address — or respond directly to this email. I love to talk with readers and am very responsive to your messages.

If you want more content, you can sign up for subscribers-only posts below. I’ll send you one or two extra articles each week, and you get access to a weekly gated thread for subscribers. As a reminder, I have cheaper subscriptions for students.

In the meantime, follow me on Twitter for related musings.