Two-thirds of southern Republicans want their states to secede from the union

Democratic support for constitutional "hardball" is a signal of broader democratic distress

Democracy needs democrats and republics need republicans; self-government can only survive if the people have faith in the outputs and outcomes of their systems of representation. You can think of the people as a set of atoms, bound together by the electromagnetic forces of their electoral laws and institutions. That force is faith in each other to make rational collective decisions and agree to minority rule when we have unpopular beliefs. How worried should we be about that force weakening to the point of collapse? About the glue, so to speak, losing its binding quality?

We know almost intrinsically that something is wrong in America. Polls can help us assess the level of mass disenchantment in the public more precisely. A new survey of voters (and some experts) by the folks at Bright Line Watch, a group of political scientists that “monitor democratic practices, their resilience, and potential threats”, contains several reasons to fret.

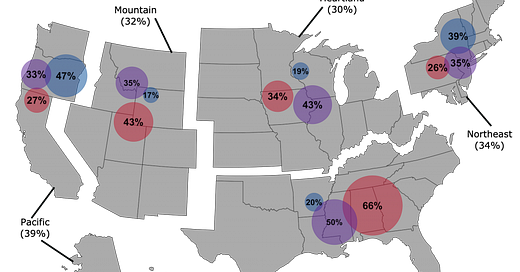

Take the shocking but not-so-surprising finding, for example, that nearly 2 out of every three southern Republicans say they want the south to secede from the union and form a smaller, regional country. The desire to break up the country — for almost any reason — would be cause for concern. The fact that disaffection is this high, and among the majority party, should make us fret about the future of the country. (I also wonder what a “normal” level of pro-secession sentiment is.)

On top of that, 43% of Independents in the “heartland” (which, according to their classification, includes the Midwest, corn belt, and West Virginia), also say they want the country to break up — that they would have more faith in a smaller group of (more like-minded) people to govern a new republic. Similarly, almost half of east-coast Democrats are in favor of creating a new state.

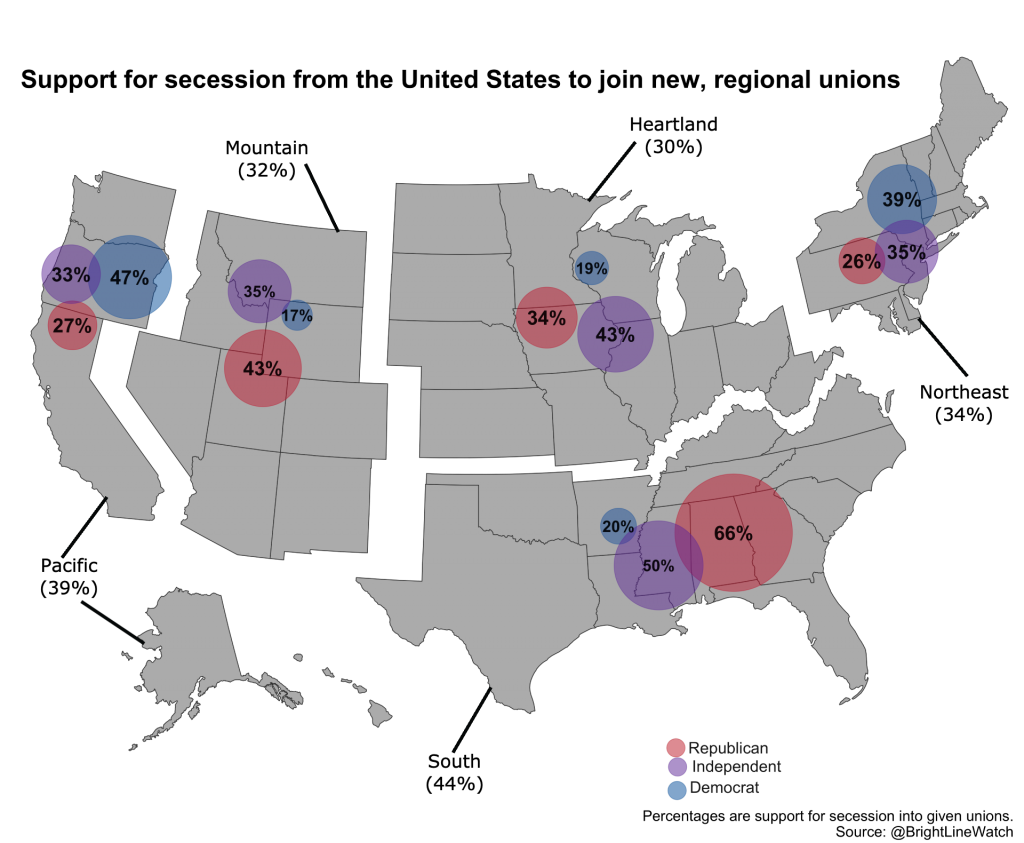

Bright Line Watch also notes that the share of Republican secessionists is higher in the South than it was in their January/February survey. This runs contrary to their expectations:

These patterns are consistent from our January/February survey, but the changes since then are troubling. Our previous survey was fielded just weeks after the January 6 uprising. By this summer, we anticipated, political tempers may have cooled — not necessarily as a result of any great reconciliation but perhaps from sheer exhaustion after the relentless drama of Trump. For instance, the historian Heather Cox Richardson posited that sustained consideration of the Big Lie narrative would diminish political ardor among Trump supporters, which she related to waning popular support for secession in the Confederacy during the spring of 1861.

Yet rather than support for secession diminishing over the past six months, as we expected, it rose in every region and among nearly every partisan group. The jump is most dramatic where support was already highest (and has the greatest historical precedent) — among Republicans in the South, where secession support leapt from 50% in January/February to 66% in June.

The authors of the report attach this graph of the shifts:

To be absolutely clear, the various attitudes driving support for secession are almost certainly not the same for both parties. The history of southern secession among whites is obviously linked to something more nefarious than the desire among northwestern Democrats for a new country. And the southern rejection of Joe Biden’s victory also comes with a dismissal of northern minority votes that evokes the history of the white southern political tradition both before and after the confederacy. Anecdotally, we observe that dissatisfaction with democracy in the south is more clearly associated with a belief that the ruling party does not have the legitimate right to rule. Many votes cast for Democrats are “illegal”, in the popular view of the southern Republican, and any valid ones are a result of buying off voters who are “unamerican” with socialist welfare policies or by coercing them with checks from elite bankers.

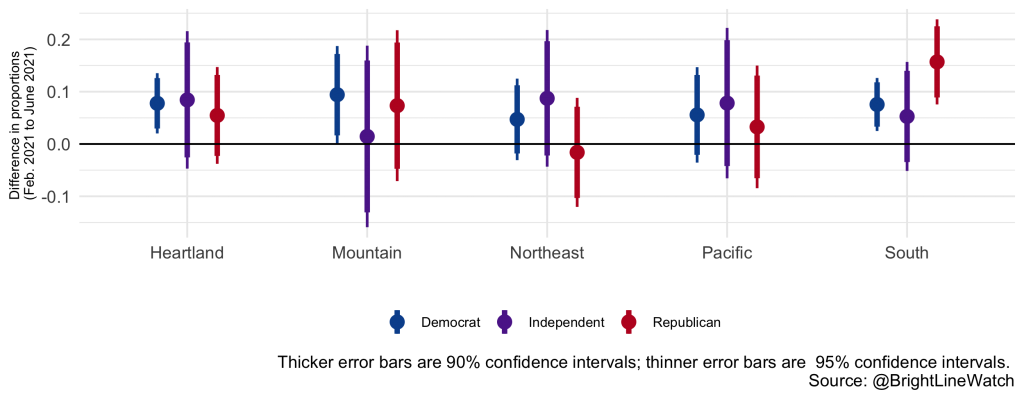

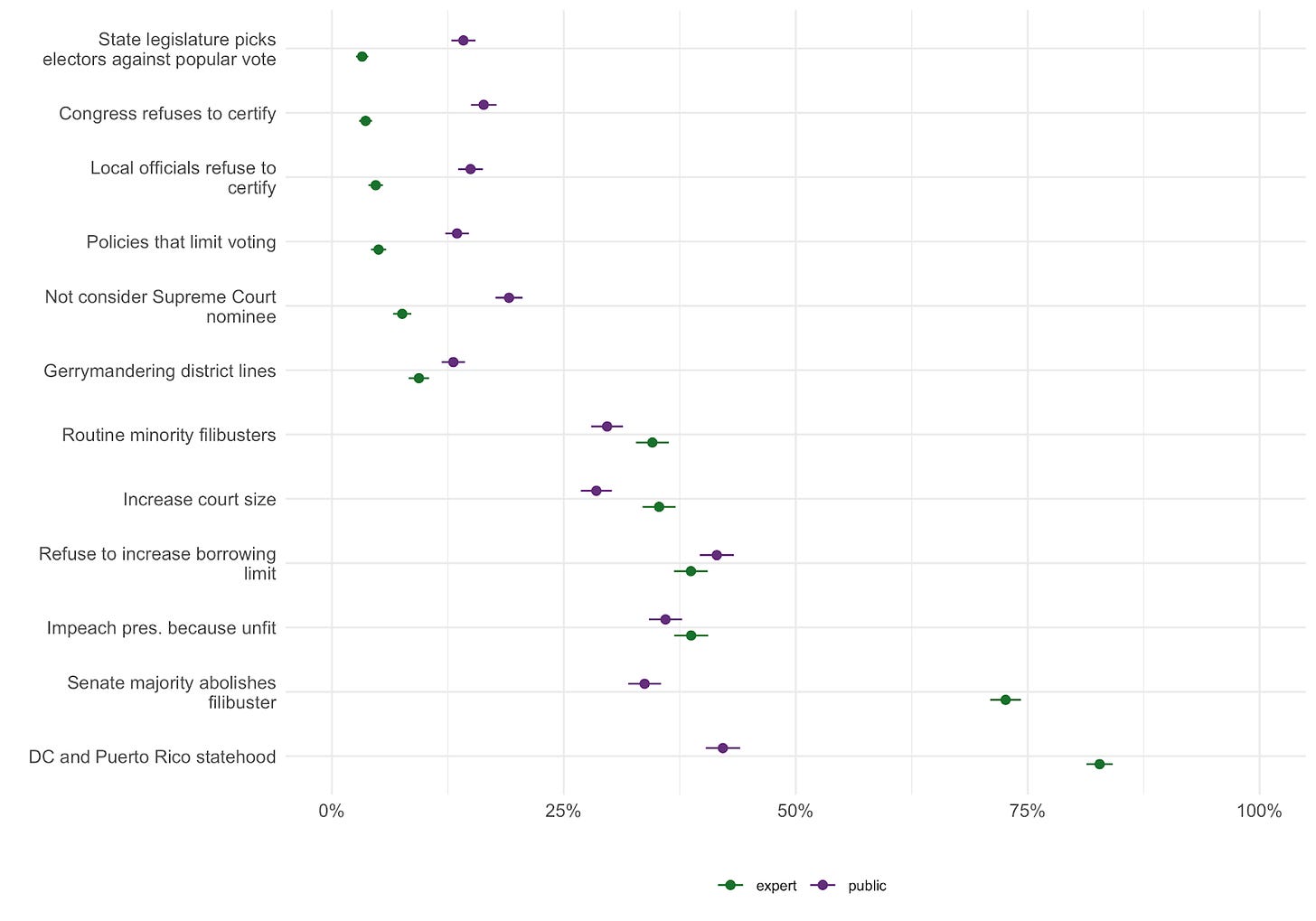

In the north, in contrast, a distaste for democracy appears driven by the unfair way Americans elect their representatives. Take the following graph. It breaks down the support for various “constitutional hardball tactics” by a person’s political party. Note that Democrats are much more in favour of reforms that would make the government more representative — such as admitting DC and Peurto Rico as states (which would decrease the malapportionment of the Senate) and abolishing the filibuster (which would empower the majority to rule) — whereas Republicans are most disproportionately likely to support minoritarian filibusters, policies that limit voting and the ability for election officials to refuse to certify elections.

In the case of these specific reforms, experts are most in line with Democrats. And they voice more concern about the proposals that Republicans are most disproportionately likely to favor. In fact, what we might consider “Democratic” hardball enjoys supermajority support from experts. That is because some “constitutional hardball” makes the government more democratic.

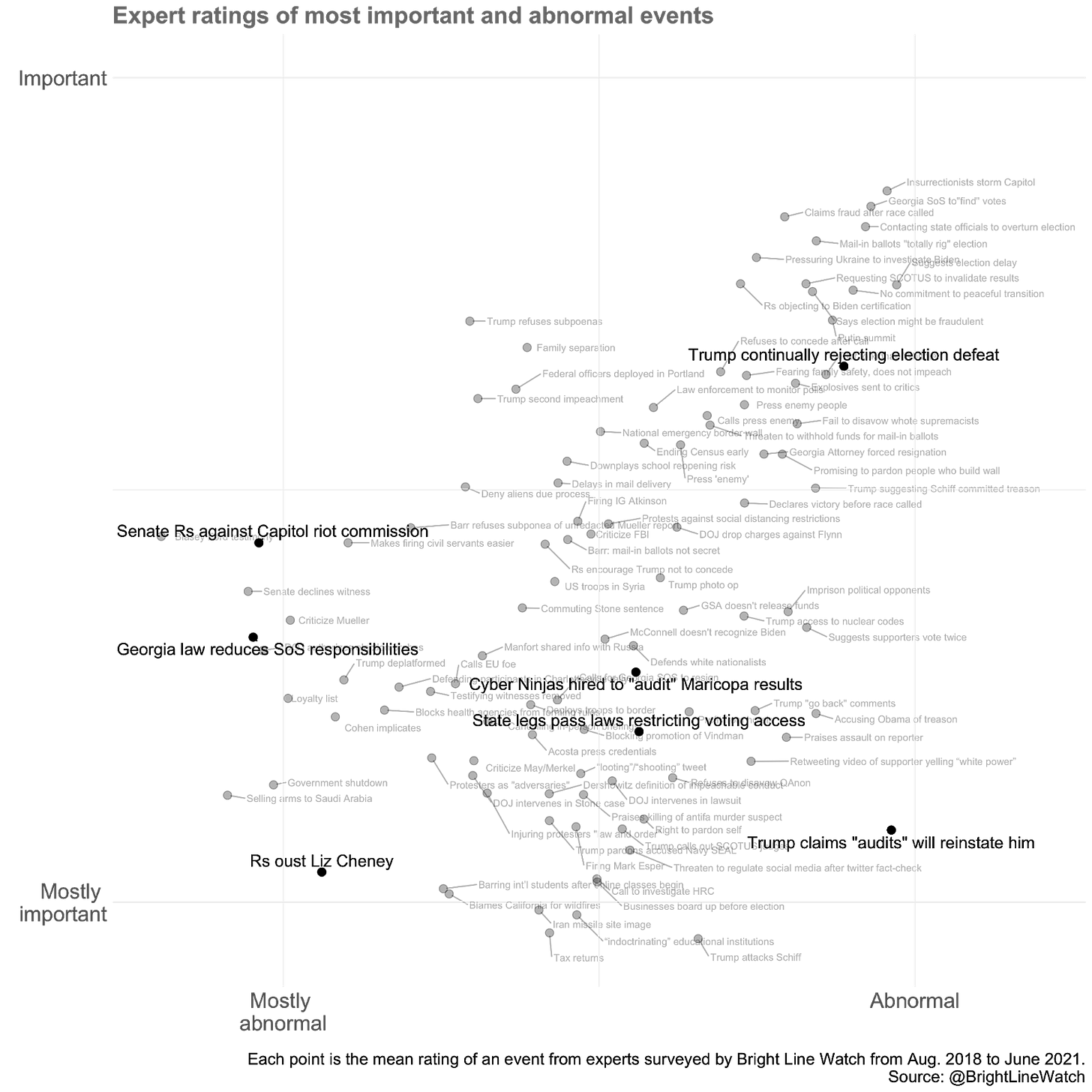

The Bright Line report also categorizes the most important and abnormal events of the last few years. Most of the ones that alarm scholars the most concern Republican attempts, at the state, local, and national levels, to overturn elections or assert unpopular rule over the country:

. . .

It should worry us, in sum, that so many Americans have lost faith in their democratic experiment. A republican government is not an easy one; it requires constant compromise, relinquishment, and defeat. More Republicans than in recent history would rather opt-out of that system, which they view (wrongly) as titled towards powerful Democrats and away from their voices. The Democrats who have these rightful concerns about democracy are not so down on the project as to support overturning elections.

The bonds between us, in summary, are severing. If we are electrons, we have bunched up by party and separated ourselves from the rest of the atom. But only one side is advocating for overturning election results. Any attempts to repaid our bonds should start by addressing that threat. We know with whom the buck stops.

If we remove all the U.S. military bases from the southern states whose populations want to secede, how much income do those states lose? https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_United_States_military_bases#Domestic_2