The future of public opinion polling

After a few bad years, it’s clear that polls have a lot to improve on — but they are still far better off than most critics allege

As I have written extensively about, most consumers of polls do not understand how public opinion surveys are really conducted — or, perhaps more importantly, how they impact our democratic systems of government. This makes errors like the ones we saw last year fodder for journalists who seem to be perpetually waiting to write scathing critiques of pollsters and election forecasters.

In the wake of polling’s performance last November, I have argued that pundits and the public simply need to lower their expectations. That would do a lot of good for helping people to have the correct reaction to the magnitude of errors we keep seeing.

However, the polls last year were wrong — perhaps even more wrong than in 2016 (see this analysis by Merlin Heidemanns). So even though I have argued that we should expect some degree of error, it is still worthwhile to ask what causes any degree of error at all. That’s what this post is about.

This week, the Cook Political Report and University of Chicago Institute of Politics held a two-day conference to figure out why, and to discuss what the future holds for the public opinion industry. There were several panels on how campaigns use polls, how some methods are outdated, and our obsession with the horse race that I found quite interesting. A final panel, at noon on Friday, talked about all three of these things, and with a few pollsters and analysts that I really admire.

The problem with polling

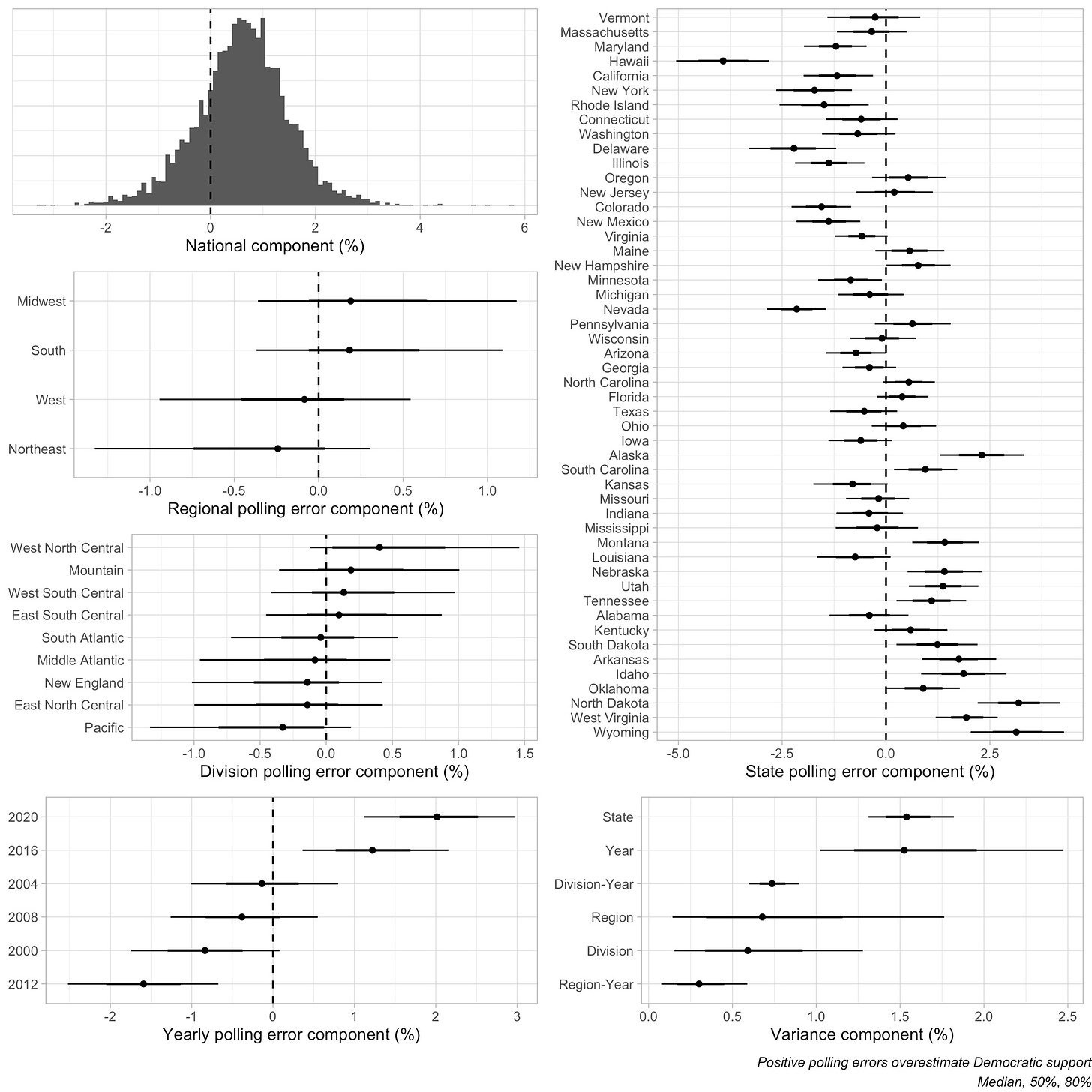

According to David Shor, the young data whiz who was canceled and fired from Civis Analytics last year, 2020 was “a very bad year for polling.” In contrast to 2016, when national polls were very close to spot-on, “there was a two percentage points bias on the presidency, and [patterns in] state bias was identical to what it was in 2016.” This suggests that pollsters both didn’t fix their errors from 2016 and that something else got worse across the board.

The causes of these errors were two-fold, according to Shor. “First was overestimating support among non-college whites. Then there was a second error, due to coronavirus making Democrats stay at home,” where they were then more likely to answer a pollster’s calls or fill out a survey online.

Eventually, the latter bias will fade. But the first bit of error will persist, in a way that weighting for education apparently does not fix. “And there will be another thing,” Shor warns. Something that will cause polls to err next time that we can’t predict in advance. “Differential non-response is shockingly volatile. Take social trust: It used to be relatively uncorrelated with partisanship, and then in 2016 it was correlated with partisanship.” Then, in 2020, coronavirus exacerbated these patterns.

Some methods also might face bigger hurdles than others.

Shor warns that the traditional RDD polling model, and phone polling in general, “has really fundamental problems… People who answer phone surveys are much, much more politically engaged than the general population. And that’s true even if you control for vote history.” In other words, if you take two identical people, with the same demographic traits and voting habits, and the only thing that separates them is that one answers a poll, the one who answers the point will be too highly-politically engaged — in ways you can’t control for. Without a doubt, this introduces partisan biases in surveys. “Answering a survey is a political act that’s super correlated with partisanship,” Shor says. Just take a look at the polling errors for the Washington Post (who had Biden up 17 in Wisconsin) or CNN (who had Biden up double digits nationally).

According to Shor, these problems are “deep and fundamental” and aren’t easily fixed by the simple changes that people “like to talk about.” Response rates are too low; responding is too polarized. The only way to get around this is to use some sort of mixed-mode poll — gather responses both from phone and online surveys and maybe even by SMS text message — and train advanced machine learning algorithms to offer sophisticated controls for biases. The future of polling, according to Shor, is much more complex — and less transparent. “The old model of polling, and of pollsters, where you have a polling shop and one or two political science grad students and you call a bunch of people doesn’t work anymore.”

For what it’s worth, Nate Cohn, who runs one of these new-model polling operations for the New York Times, mentioned that their predictions for turnout only explained about a point of their bias in vote share. That wouldn’t explain their nearly five-point error in Wisconsin or two-point miss in Michigan. Other factors, such as differential partisan non-response, also shaped the error. Though to be sure, for other pollsters with different modes of predicting likely voters — notably, those that lack access to administrative data — their turnout models could have introduced larger biases.

Beyond the horse race

Ashley Kirzinger, who does telephone and mixed-mode polling for the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF), largely agreed with Shor’s assessment about the future. “We have to innovate,” she urged repeatedly. But she also underscored that the horse race is not really what we should be focusing on anyway. “When we’re looking at elections,” she says, “we’re looking at the issues that are really driving voters.” As if to prove her point, the KFF does much more polling on issues like covid-19 and health care than they do about the horse race. Kirzinger's view is that poling actually addresses the why of politics than the what, despite what the public sees.

Cornell Belcher, the famous former DNC pollster and president of Brilliant Corners, offers a similar view from the world of campaigns and activist groups. There, the polls serve an entirely different purpose than they do in the public: informing strategy. Belcher: “The least important number in a poll is the horse race,” Belcher said. “I’m using polling to figure out how to move the electorate along, why people are there… and how to move them one place or the other.” Looked at in this way, the horse race is not the independent information from a poll, but rather the dependent variable that he is trying to shape.

Saying he was inspired by W. E. B. Du Bois’s work on black living in Philadelphia, Belcher explains he uses polls more as a tool of sociology than handicapping. In the political context, this amounts to tracking favorability numbers among certain demographic groups and crafting advertisements and message strategy to to “move them where they need to go” so he can win campaigns. (This is consistent with a lot of what I’ve heard over the past few days from other campaign pollsters.)

However, if horse race polls are wrong, there is reason to doubt some of the campaign narratives that they help fuel. Shor mentioned that the narrative that education polarization decrease turned out wrong; the gap between college and non-college-educated voters actually increased this year. Polls also missed the magnitude of Republicans’ surge with Hispanic voters; in some places, Democrats lost up to 13% support on vote share among Hispanics, when polls suggested much smaller shifts.

This means that, when we look back, we have to be fairly scrutinizing of our methods. But it helps to be clear about the weaknesses of the polls, whatever they’re used for. “Every cycle there’s something we have to solve for,” Belcher says. “And ultimately, we can’t! There will always be that error in [the polls].”

The stakes could hardly be higher

Cornell Belcher asks: ”Are we in fact misinforming the public? Yeah, we are. We gotta do a better job at informing the public at exactly what the polling means.”

The panel was also asked about their feelings on election forecasting. Nate Cohn, who (by his account) refused to participate in the New York Times’s modeling efforts in 2016, says that it has “become an unhealthy obsession” and that they offer a false sense of precision. There are “too many variables in past to be sure it’s predictive of the future,” he says. For what it’s worth, I have written a sort of mea culpa on my 2020 forecasting efforts (which I view as largely successful — our model was less wrong than the polls alone!) here.

David Shor, for his part, thinks that “forecasting is an easy target. It’s good and important.” After all, the biggest question of the election is who will win — we want to provide the most accurate answer to that question as possible. It’s worth noting that the world before election forecasts were full of “ad hoc” takes and a focus on outlier polls. A world of sophisticated pre-election models developed by statisticians and data scientists is certainly an improvement. “One of the biggest things people want from our field… is to know who’s gonna win. It’s really important to do the best job you can at that.”

But while forecasting is a public (and, in many cases, private) interest, it’s also very normatively important from a small-d democratic perspective. “When Democrats shot up in the polls” in June and July of 2020, Shor attests, “Republicans and Donald Trump changed a lot of their messaging and tact [against racial justice protestors].”

In an alternative world, with the “absence of formal algorithms, people are going to make judgments on whatever polls they see and will be driven by their cognitive biases.” Cohn put it similarly: “So long as political decision-makers are deciding what direction the democratic party will take or what races to invest in, having an accurate horse race number is crucial. That’s also true for everyday citizens,” who give millions of dollars to campaigns themselves.

A crisis of confidence

Polls are inexact tools, and they do not fit the purpose of providing hyper-accurate predictions for elections. Most political journalists and media outlets don’t understand this. “Media has to be careful to avoid drawing false narratives from the horse race,” Belcher said.

And he’s right. Especially in the context of election predictions, polls are rather inexact tools; there is both an art and science to measuring pre-election vote intentions that is hard to get exactly right. One of the reasons that people like me do forecasting models at all is to get a better handle on the error from individual polls. For instance, although polls report a margin of sampling error of around 3% for a 1,000 person poll, research has found that the “true” margin of error is probably at least twice that high. If you want to predict a candidate’s vote margin on election day, to account for all the sources of unignorable error that are unknowable before election day — stuff like knowing the right partisan make-up of the likely voting electorate — then you’ll need a margin of error close to 12 points for any given poll, and maybe 8 or 9 points for a polling average.

Despite this, the media has reacted to recent misses as if polling faces a “catastrophe” of misprediction. These characterizations are overblown: on the whole, polls are no less accurate than they were a decade or so ago. In fact, polls have gotten meaningfully more accurate as time has elapsed.

Despite this, fewer and fewer Americans put their trust in pollsters to accurately reflect the will of the people. Media pollsters have suffered especially hard. Over the past hundred years, accusations of bias, manipulation, and misrepresentation against news outlets have left many firms marred by an angry and rancorous public.

The Pew Research Center found that Americans would award pollsters a paltry “C+” grade for their performance in the 2012 election. In 2013, another pollster called Kantar found that only half of adults believe polls published by professional firms, and most distrust those released by the media. After 2016, trust plummeted even further; only 12% of voters admit to believing most of the polls they see published in newspapers or on television — and a 2017 poll from Marist College revealed that 61% of American adults say they don’t trust polls “very much” or “at all.” As an institution, people distrust the polls more than they distrust the CIA, FBI, and the judiciary, and are almost as wary of them as they are of Congress (which has inspired remarkably little trustworthiness over the last few decades).

I think this is all dramatically overblown, leaving me to wonder whether how different our conversation about "the future of polling" would be if people just lowered their expectations for the precision of horse-race forecasts down to the appropriate level. The easiest way to make progress on this front might just be for pollsters who refuse to perform more accurate calculations of uncertainty to just double whatever traditional margin of sampling error they're reporting.

On the part of the panel, the members had fewer thoughts on — as there was less time devoted to — ways to shore up public confidence in the industry. That is fair, as it is largely the media’s fault that impressions have sunk in the first place.

The future of public opinion polling

For my part, I think the future of polling looks something like this:

Media outlets report less on polls released by small, low-quality outlets that release polls for clicks and clients, instead of screening polls to ensure they meet strict methodological standards and are based on sound judgment and theory.

Most polls are done using multiple modes, and the collection of data increasingly moves online with sophisticated algorithms to adjust for various biases relating to non-response and non-selection

Political journalists will present a more informed picture of polling’s precision, ignoring traditional margins of sampling error and exercising judgment over how accurate a poll claims to be. Gone will be the days, I hope, of pretending that an RDD poll has a margin of error of 3 points on a percentage. It’s more like 6 or 7, depending on the design (or higher, depending on the sample size).

More outlets will use prediction models that show large margins of error for polling averages — on the order of 9 or 10 points on a candidate’s vote margin, depending on the state. These models will also offer corrections for the various ways in which a poll is conducted. We have known that partisan non-response is a big source of error in the polling, for example, yet only the model I built with my colleagues offered an adjustment for it. (This may have led to our best-in-class projections of Trump’s vote share, which were more accurate in red states than the competition’s.)

Aggregation of non-horse-race polls will become more popular, with organizations presenting their estimates of public opinion on a variety of policies at the national and state level. Organizations like Civiqs are leading the way on this, but media outlets could do more to collect information on important topics and present it to their readers.

For what it’s worth, I also hope this future involves more people paying attention to the New York Times election-night needle.

…

People often act as if the future of polling is dark — a blanket covering the industry as trust in the nerds that collect and crunch the data on public consciousness declines.

But it seems to me that the future of polling, from an abstract sense, is the same as it ever was. Pollsters have faced many “catastrophic” failures before and have always dragged themselves over the hump. If they innovate as they say they will, they should be able to move on once again. We should hope so — for democracy’s sake.

Editor’s Note: If you found this post informative, do me a huge favor and click the like button at the top of the page and the share button below. As a reminder: I’m fine with you forwarding these emails to a friend or family member, as long as you ask them to subscribe too!

I wonder if a sort of Meyers Briggs poll would work.

When you take that test, they never ask something like "Are you an introvert? Yes/No" but in the end, they come to that conclusion.

If you could design a set of questions that gets at the fundamental belief system of a person such that they can't offer enough fake responses to mess with it (you could detect a pattern of faking) then you could compare where they end up in your "personality/belief matrix" with the positions being advertised by different campaigns.

With that comparison, you would then draw your conclusions about how they will vote.

This sort of poll could be made very attractive online because at the end you reveal something about the poll participant which keeps them clicking through to the end.

Give it a clickbait headline like "Where do you stand in comparison to your neighbors?" or "Are your beliefs on the winning side?" or whatever and make most of the questions amusing...when you pose scenarios and ask if they are more or less likely to respond in a certain way.

At the end give them accurate graphs, etc. so you are not being deceptive about what they'll get.

You'd have to decide how to target your ads and compare them to voter databases, etc., all that usual stuff.

This could be very complex and nuanced, but with a huge enough amount of data and perhaps some machine learning, it could possibly end up being pretty close...at least as close as the Myers Briggs test gets, which is sometimes quite accurate and usually at least in the same part of the ballpark. More data allows for corrections.

This would be inviting/enticing people to take a poll rather than forcing yourself into their lives and insisting they take a poll, which isn't working out so well at the present.

Too much security.