What if people who watch Fox News watched CNN instead? | No. 191 – April 10, 2022

An ambitious social-science experiment raises alarms for democracies with popular partisan media outlets

Welcome to the first weekly edition of Democracy by the Numbers, a rebrand of my blog to make it more directly compatible with the core themes of STRENGTH IN NUMBERS, my book on polls and democracy which comes out this summer. Some readers will have noticed the soft launch of this title in a recent newsletter on fake polling data “collected” in Iraq from 2006 on. And I have sent another post on the global political realignment away from class divides and onto educational attainment, which has led to the rise of politicians such as Donald Trump in America and Marine Le Pen in France. That was a fun one to write.

While the content of this newsletter will remain the same, the framing will become a bit more democracy-oriented. We will still talk about voter psychology, voting behavior, elections, and public opinion more broadly — but always with representation and the will of the people in the back of our minds. Democracy by the Numbers is about numbers, sure, as this blog has been, but also formally more about democracy and the influence of the governed.

Given this news, it is fitting that we have a major social-science experiment to cover this week. It is as impressive as it is alarming.

In this blog, I have often repeated the refrains of pollsters and political scientists that democracy requires an ideologically neutral information environment to optimize electoral accountability. If people are only fed a diet of propaganda or ideologically-biased media, how can we expect them to make rational decisions on average? That raises a few questions: How does democracy work in environments with partisan media sources? What would happen, for example, if people who watched Fox News watched CNN instead?

Those are the questions that David Broockman and Joshua Kalla, two political scientists, ask in a new paper “The manifold effects of partisan media on viewers’ beliefs and attitudes: A field experiment with Fox News viewers.” It is a huge study over five years in the making.

Broockman and Kalla conducted a randomized field experiment that recruited over 700 Americans who regularly watched Fox News and then paid 40% of them to watch up to 7 hours of CNN per week instead, and investigated the effects of the treatment. They did this by first asking the participants a series of questions — about politics, the media, recent events, etc — then providing the treatment (pushing some to watch CNN and others to keep watching Fox), then, finally, after the treatment period, asking everyone a new set of questions on the same topics.

As a result of incentivizing these Fox News viewers to watch CNN instead, Broockman and Kalla observed “substantial learning” among the treatment group. They became more factual in their perception of current events and their knowledge about the 2020 presidential candidates’ positions when compared to the group that kept watching Fox News; they became more aware of events that CNN covered during the period and Fox didn’t (covid-19 instead of the 2020 racial protests) and they even became slightly more negative in their evaluations of Donald Trump and Republican elected officials.

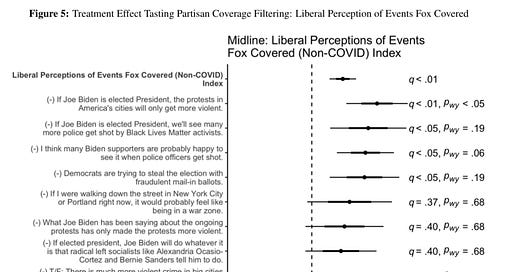

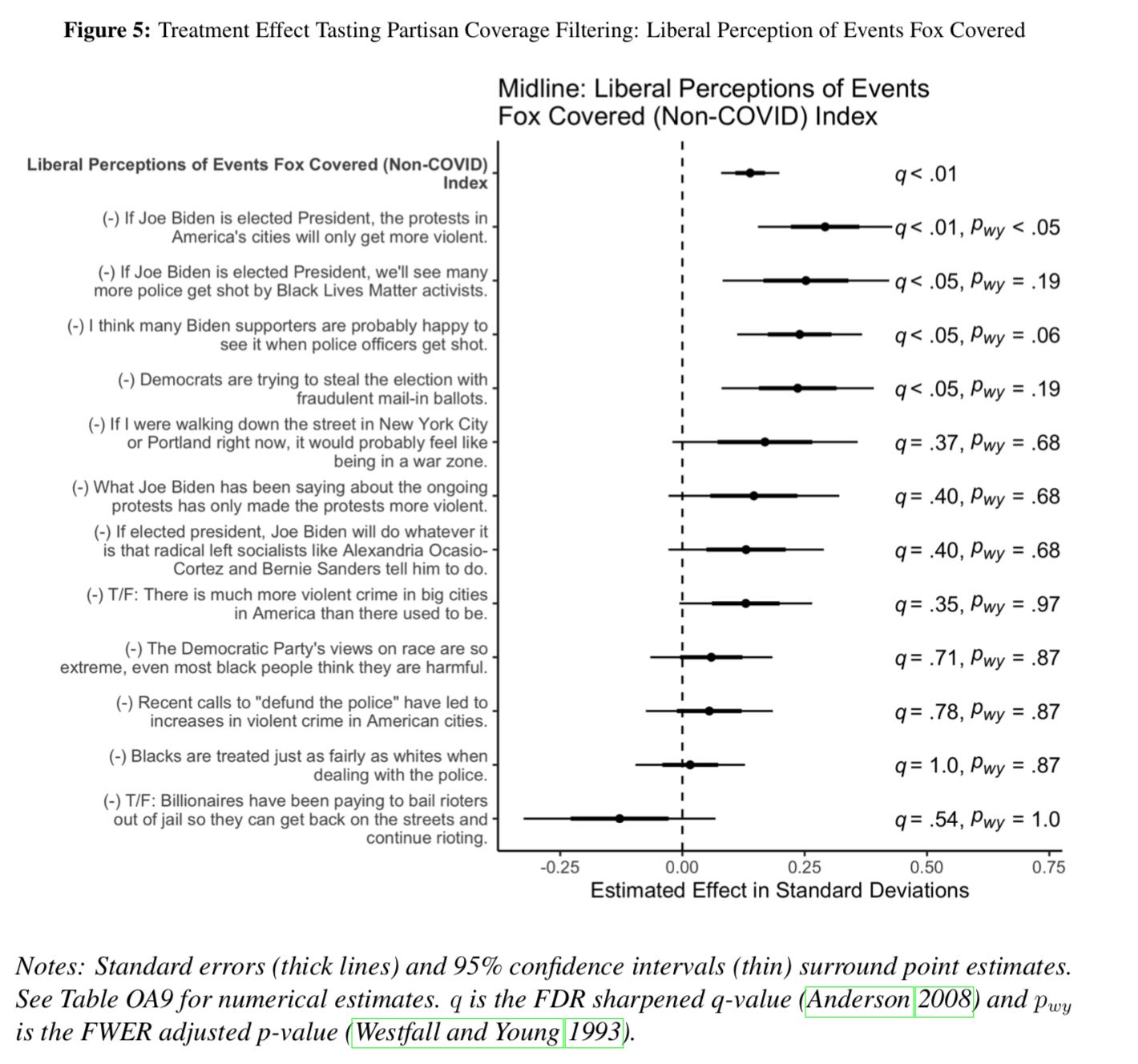

The authors observed the biggest effects on participants’ perceptions of events. They became less likely to believe Democrats were trying to steal the election with fraudulent mail-in ballots (a 0.24 standard-deviation decline), for example, and less likely to think Biden wanted to eliminate all funding for police departments (0.17 SDs). See here for more:

This study is important for a variety of reasons. For one, it is the first large study to look at the real-world effects of changing voters’ information diets in the modern polarized era. Field experiments of this depth and scale are also no easy task. They require a lot of time and resources, creativity, and academic imigination. Broockman and Kalla did something genuinely impressive in terms of the social science.

The study also reveals a lot about the impacts that partisan media can have on democracy, and how they do that. We have known for a while, for example, that viewers of Fox News tend to vote for Republicans at higher rates than Democrats, but have only had theories about how that happens. This paper suggests that Fox accomplishes this mainly through agenda setting and media framing. By covering issues that are better for right-aligned politicians, and by selectively presenting information that is flattering to Republican ideologues, they juice support for the right.

It is also one thing for attention to a single media outlet to unilaterally affect awareness of and beliefs in liberal subjects. It is another thing entirely to show that watching Fox News is correlated with believing false claims and misinformation, as Broockman and Kalla do. The study found that exposing viewers of Fox News to CNN could marginally improve their engagement with fact-based reality on general politics and things like covid-19. That is reassuring, though the magnitude of the effects was disappointingly small.

So, where does that leave us?

One way to synthesize these points is to ask how partisan media affects how people hold politicians accountable. If, say, Republican politicians are acting against the interests of Republican voters along economic lines (by trying to slash medical services and cutting the child tax credit, for example), but viewers are only ever presented with programming on subjects and events that affirm their worldviews on ideology and social policy (such as on immigration or violence in cities), they are not going to be able to hold politicians accountable for any economic impacts on their lives. They can also accomplish their goals by selectively hiding information: for example, on the role that Republican politicians played in (not) addressing covid-19 or enabling the January 6th, 2020 insurrection.

The authors are not necessarily optimistic. On the one hand, their study shows how curbing viewership of partisan media could correct aggregate levels of belief in popular conspiracies and misconceptions about politics and events. But on the other, people are unlikely to make this switch on their own. “Viewed from this vantage point,” Broockman and Kalla conclude, “partisan media is not simply a challenge for the opposing party—it may present a challenge for democracy”. Such is the nature of partisan groupthink.

Posts for subscribers

If you liked this post, please share it — and consider a paid subscription to read additional posts on politics, public opinion, and democracy.

Subscribers received three extra posts since the last weekly edition:

What I’m reading

I’m currently reading Pachinko, an epic novel about three generations of 20th- and 21st-century life in Korea (and so much more), and a finalist for the National Book Award in 2017. On deck is The Precipice: Existential Risk and the Future of Humanity, a 2020 non-fiction book by the Australian philosopher Toby Ord.

That’s it for this week. Thanks very much for reading. If you have any feedback, you can reach me at this address (or just respond directly to this email if you’re reading in your inbox). And if you’ve read this far please consider a paid subscription to support the blog.

As previously stated, education and propaganda are key. Thomas Pikkety says "...what really matters for economic prosperity is education and relative equality in education.8

8

There is compelling correlation between income inequality and education: Researchers have found that there is a little more than a 30 percent probability of gaining entrance to an institution of higher learning for young adult Americans whose parents’ incomes are within the bottom 10 percent. That probability rises to 90 percent for children whose parents’ incomes are within the top 10 percent.

The key reason the U.S. economy was so productive historically in the middle of the 20th century was because of a huge educational advance over Europe. In the 1950s, you have 90 percent of the young generation going to high school in the U.S. At the same time, it’s 20 to 30 percent in Germany, France, Britain, Japan. The story that Reagan tried to tell the country in the ’80s, which is basically forget about equality, the key to prosperity is to let the top become richer and richer — it doesn’t work."https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/04/03/magazine/thomas-piketty-interview.html