What fish can teach us about democracy 📊 September 12, 2021

Plus: posts on social sorting, public opinion twenty years after 9/11, and improving representation in Congress

As promised, here are a few paragraphs adapted from the draft text of STRENGTH IN NUMBERS, which has just gone into production at W. W. Norton and should be out next summer. This section of the book presents various challenges and responses to the argument that the people can, in the aggregate, make “good” and “rational” decisions on public policy and other matters of government. We begin with the development of the concept of public opinion in political philosophy, tracing its roots back to Plato and Aristotle and beyond. We read primary documents from the Enlightenment and around the time of America’s founding to assess the extent to which enfranchised people were supposed to be sovereign self-governors. We observe the rise of polling and some of the first criticisms of “government by survey” from Walter Lippmann and others. And we review the empirical literature on the matter.

The tie-in? While we get into the science of polling later, this theory is the foundation to building a broader understanding of the potential for public opinion polls to help the people get what they want from their leaders.

[So, cutting to the text now:] It is ultimately hard to answer the question of whether uninformed people can make the “right” decisions. Our sample size is small and the target variable is hard — if not impossible — to measure. A hypothetical study for such a question would need to be conducted on the scale of a whole population, with proper definitions for the “correct” decision on a range of (or all?) issues, and it would have to see information to random subsets of voters and observe their behaviors.

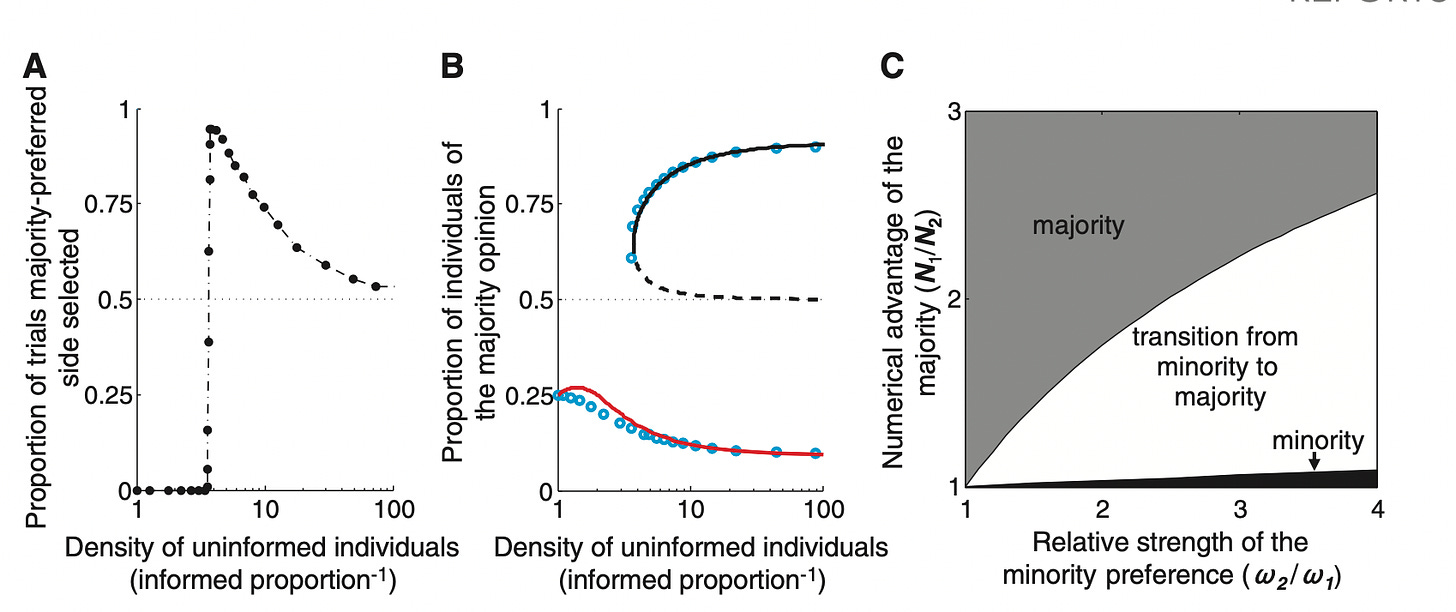

We can draw on research from the animal sciences. One paper from a group of scientists led by behavioral biologist Iain D. Couzin found that schools of fish can exhibit “democratic consensus” when they are searching for food. The team of researchers split one species of fish into two groups: one that was trained to swim towards a blue dot for a food reward, and another that followed their evolutionary instinct towards a yellow dot for food. When the two groups were placed together, with more blue fish than yellow fish, the minority's stronger ”opinion” dominated the group's overall behavior and the combined school swam towards the yellow dot. But when the researchers added fish with no training, the fish increasingly swam toward the majority-preferred blue target.

The researchers used mathematical models to argue we can expect similar findings among other groups. They offered a conclusion about the impacts for human societies:

Conflicting interests among group members are common when making collective decisions, yet failure to achieve consensus can be costly. Under these circumstances individuals may be susceptible to manipulation by a strongly opinionated, or extremist, minority. […] Here, we use theory and experiment to demonstrate that, for a wide range of conditions, a strongly opinionated minority can dictate group choice, but the presence of uninformed individuals spontaneously inhibits this process, returning control to the numerical majority.

Abstracting the findings to our broader theory of public opinion, an ideal process of determining opinions would be more deliberative than survey-taking is today. You first have a pollster assess the idea of the public on an issue, then have the press disseminates the quantified will of the majority to the people, allow some time for community leaders to foster debate about the issue after receiving such information, then take a final poll of the issue to arrive at an informed measure of opinion. Preferably, the polls probe a range of attitudes about one topic, rather than just asking if people support or oppose a policy.

Though we have not achieved this ideal, modern political science nevertheless suggests that the rationality of America in aggregate is strikingly robust. In The Rational Public, a 1992 book on trends in polling throughout the 20th century, political scientists Benjamin Page and Robert Shapiro meticulously trace the contours of the public’s attitudes on a range of key issues. Their work supports Aristotle’s theory that public opinion is wiser in aggregate than any individual person, who can fall prey to a lack of information and make an “irrational” decision about a policy that could benefit them. “Americans’ collective policy preferences are real, knowable, differentiable, patterned, and coherent,” the authors write. They are “generally stable; they change in understandable, predictable ways.”

Page and Shapiro find a reasonably good match between real problems in the government and the issues that people rate as most important to them. People “take cues” from like-minded citizens to inform their choices. In their conclusion, they write that the public is “considerably more capable than the critics of majoritarian democracy would have us believe… the classic justifications for ignoring public opinion do not hold up.” And while people do not always make the “right” decision, if they are presented with the right information they usually come to the natural conclusion from that data; and they sometimes even signal support for fundamental rights when leaders are opposing them.

…

The book goes on to talk about the birth of polling. But I thought you would all find the study on fish interesting. The literature suggests people can be herded in the right direction by the insightful and informed members of the whole. We should take extra note of the dynamic whereby uninformed, unengaged citizens counter the bullying of vocal minorities and help the public move towards the target — hopefully, this happens more often when the minority is in the wrong.

The complicating factor is, of course, that people are not fish!

Posts for subscribers

Subscribers received three posts over the last two weeks. Consider a paid membership to read them, or email me if you’d like a free trial.

On deck: A post tomorrow aggregating the polls of and providing a guide to Califronia’s recall election, which will very likely go Gavin Newsom’s way despite the media hysteria over the last three months. I argue pundits would have seen this coming if they analyzed the polls correctly and familiarized themselves with the historical dynamics of recall elections.

Assorted links

My writing:

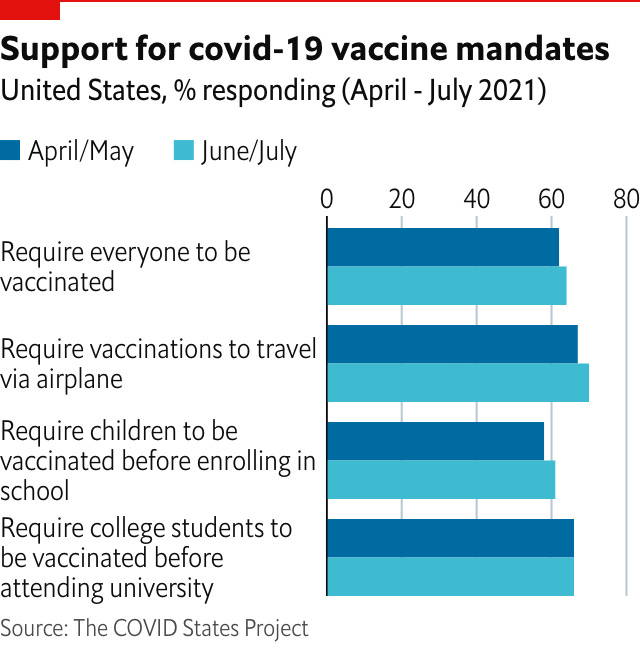

Check out our Economist commentary on the Biden Administration’s new covid-19 vaccine mandate, which is popular (and, more importantly, effective!).

Recommended reading:

One of my premium newsletter items above talks about this interactive from Lee Drutman and the New York Times. It matches up the results of a quiz on your issue attitudes with some modeling of actual survey data to place you alongside other Americans in two-dimensional ideological space. Very, very cool — and congrats to everyone involved.

Thanks for subscribing

That’s it for this week. Thanks so much for reading. If you have any feedback, please send it to me at this address — or respond directly to this email. I love to talk with readers and am very responsive to your messages.

If you want more content, you can sign up for subscribers-only posts below. I’ll send you one or two extra articles each week, and you get access to a weekly gated thread for subscribers. As a reminder, I have cheaper subscriptions for students. Please do your part and share this article online if you enjoyed it.