What education polarization and political arithmetic can tell us about 2022 — and the next decade

Class polarization is a long-term trend in US politics and abroad. It is rocking our electoral institutions

Happy Saturday, subscribers!

Ezra Klein has written a great column for the New York Times Opinion section this week on the ongoing debate among Democratic strategists (and on Twitter) over how they should build on their 2020 victories while reversing some of the longer-term trends in the electorate that are hurting the party’s prospects: namely, polarization in vote choice by educational attainment. Klein features work by David Shor, a celebrity Democratic data analyst and leader of the so-called “popularist” theory of targeted messaging and political campaigns.

We’ll talk more about popularism itself in tomorrow’s all-recipient email. For now, I want to send along a two-parter. First we’ll do some simple descriptive work and talk about the history of class polarization (as measured by proxy in educational attainment). Then, I’ll show you why much of the backlash to Shor’s modeling a longer-term forecasting is misguided — and largely missing the point of the exercise entirely.

I. We have decades of class polarization (along educational lines) that will be hard to undo

By training predictive models on historical election results and demographic data, Shor can project future election outcomes conditional on overall support for Democrats and pre-specified levels of educational polarization in the electorate — specifically, by moving up or down the share of the vote Democrats will receive among college and non-college educated voters (presumably in different demographic groups, though I haven’t seen the model code itself so can’t be sure).

I think this is pretty cool! In part because I’m a huge fan of simulating election outcomes (that’s how I started my career!) but also because it lets Shor show us, the readers, what to expect in 2022 if Democrats enact various changes to their messaging that he argues could help them win back (some) non-college-educated Americans, especially whites. Shor argues Democrats should emulate Obama’s 2008 run for president, decreasing the amount of time they spend talking about race, racial issues and immigration and instead focusing on popular economic issues, such as a wealth tax and Medicare drug price negotiations.

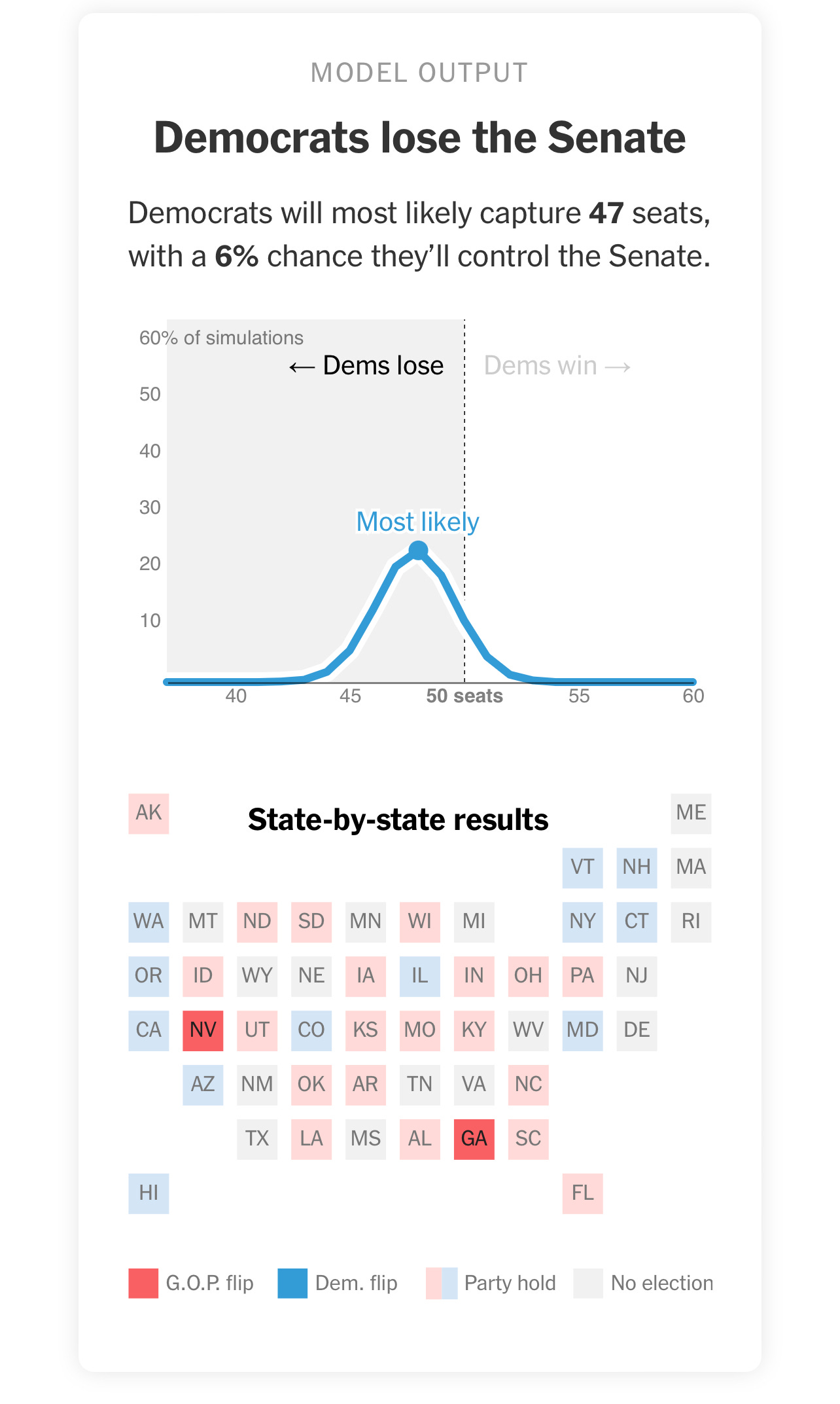

Here’s a prediction of potential Senate outcomes in 2022 if we tell Shor’s model that Democrats will win 50% of the implied two-party popular vote while education polarization and straight-ticket voting will increase versus 2020, as they have in almost year since 2008:

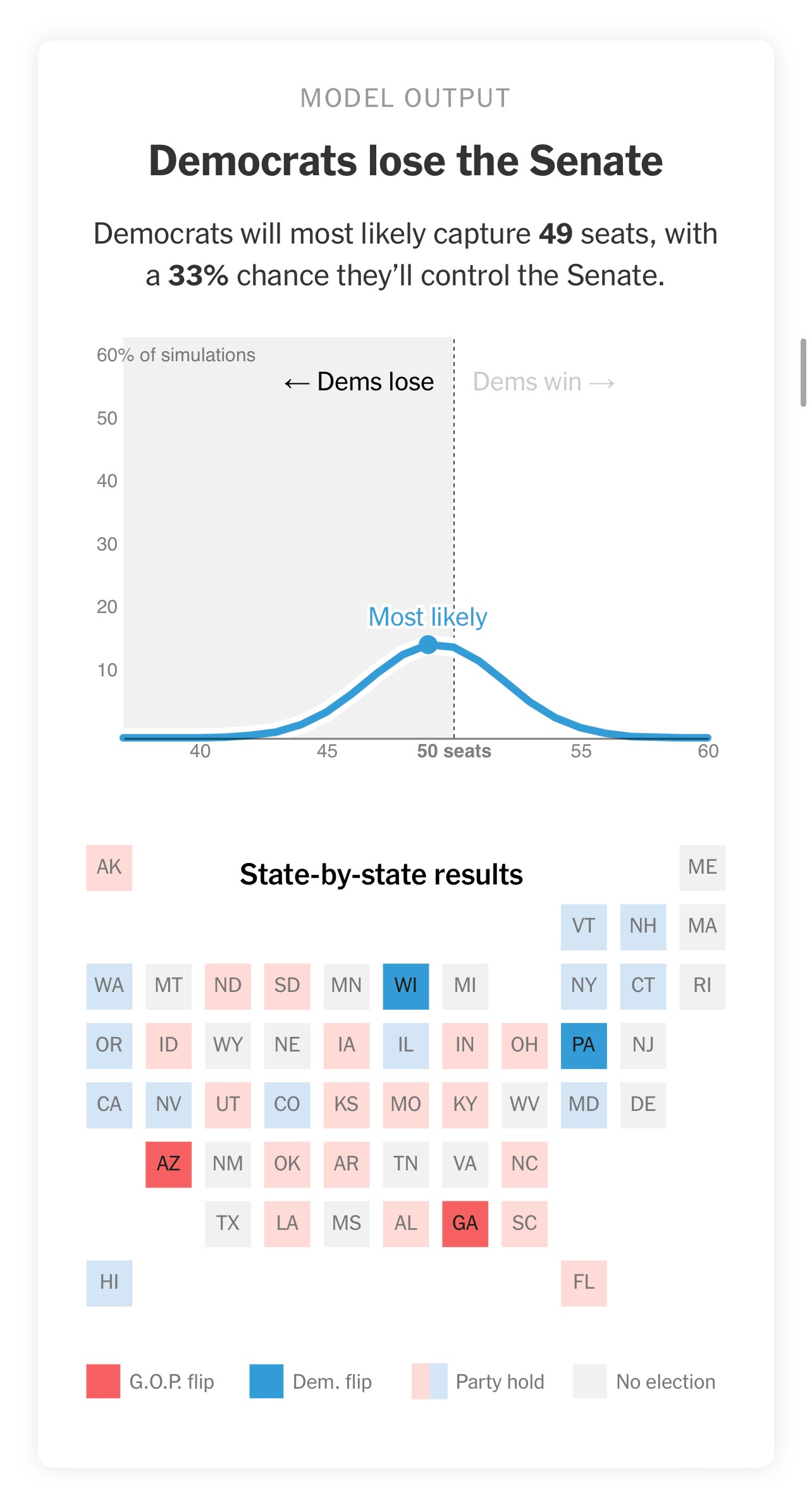

And here’s another simulation if you think education polarization will go down. The Democrats’ odds improve a lot, but they are still behind due to the nationwide 50% support and pro-Republican tilt of the Senate.

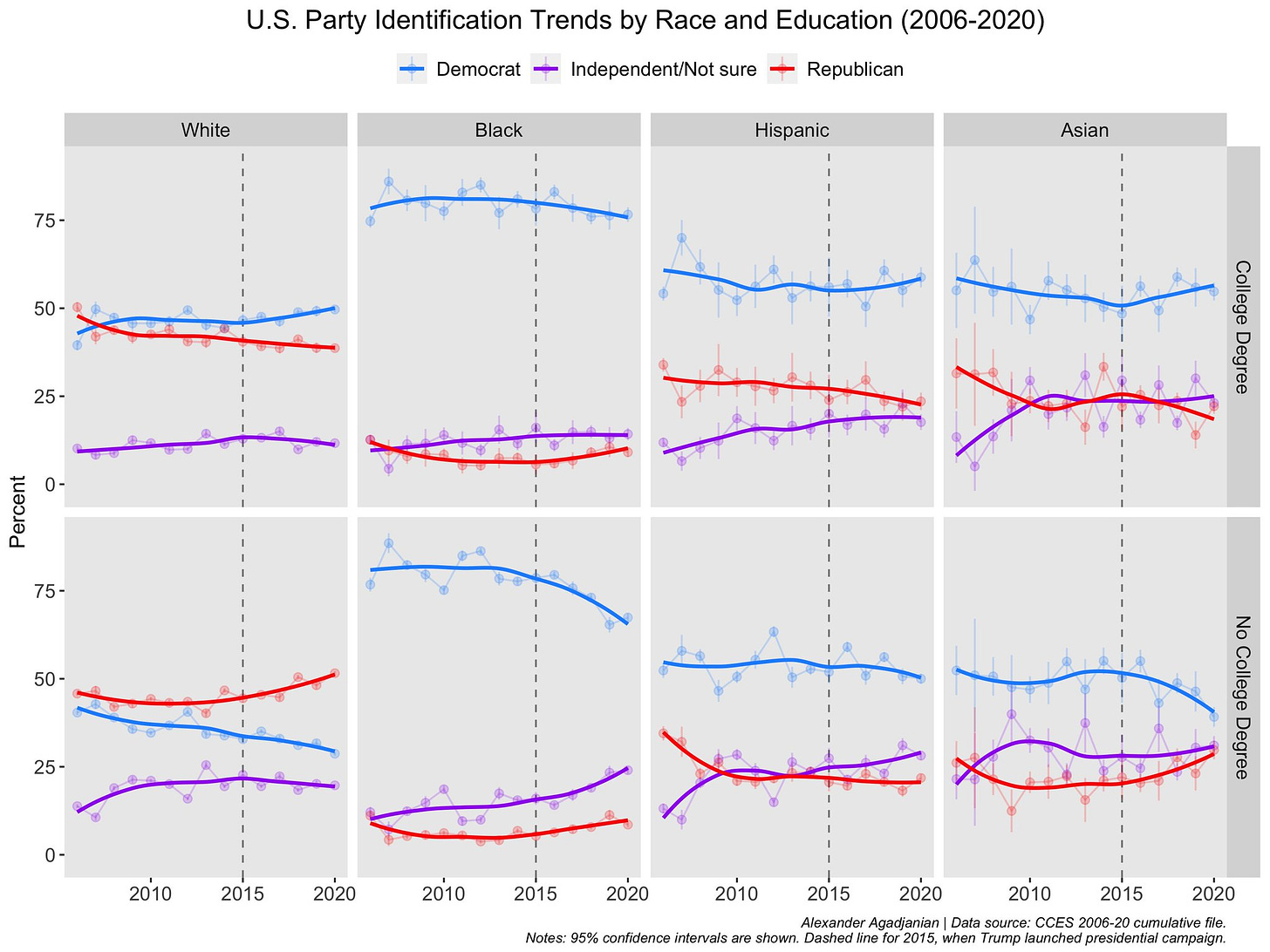

One thing I find missing in Klein’s piece, however, is an illustration of just how much we have polarized by education since 2008. Luckily, Alexander Agadjanian, a Berkeley political science PhD student and good friend of mine, has produced a nice chart on the matter:

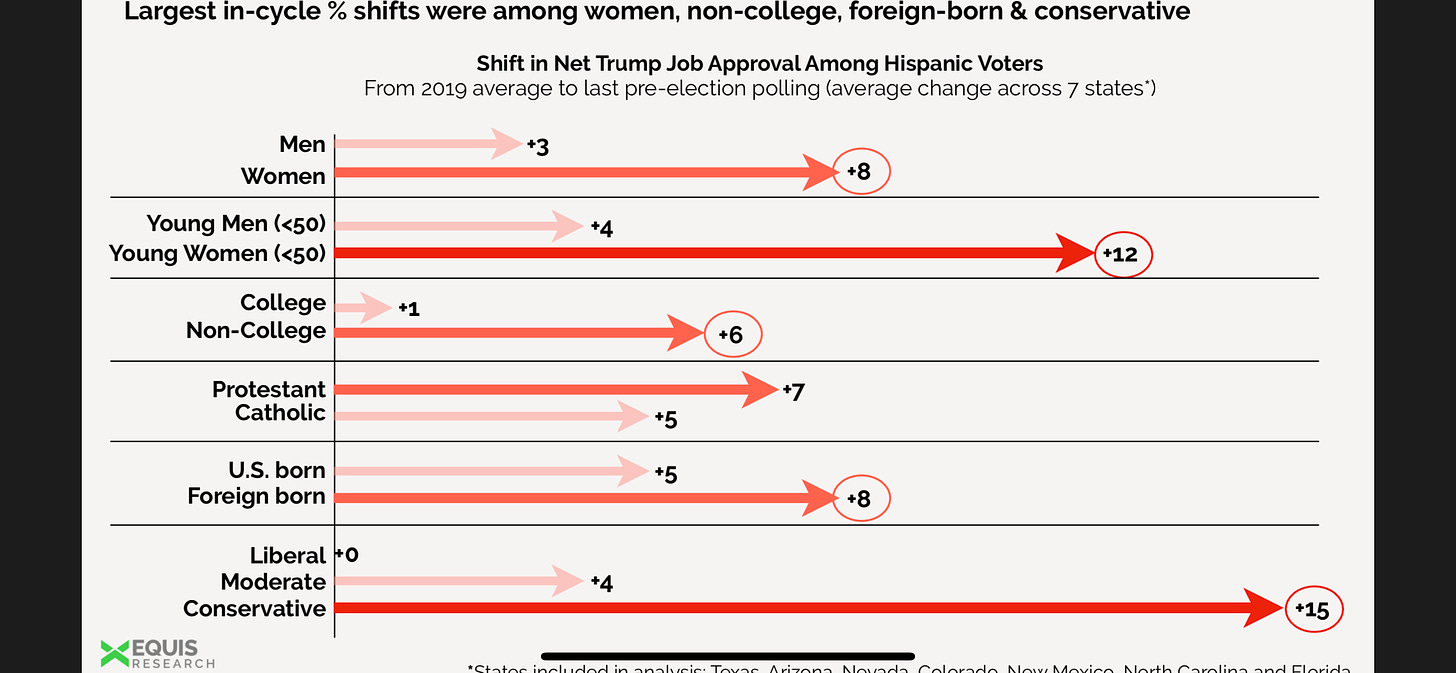

Alexander’s crunching reveals a sharp decrease in the share of non-college-educated voters calling themselves Democrats *across age groups* since 2008. Eyeballing the chart, there has been a roughly 30 percentage point increase in the Democrats’ party ID margin over Republicans’ for college-educated v non-college-educates voters, from about 5 points in 2008 to 35 points today. There has also been increasing education polarization among Black and Asian voters, according to the CCES. And while these days don’t show increasing educational polarization among Latinos, other studies, such as this one from a pollster that specializes in polling Hispanics, does find one:

This paints a picture, I think, that shows a significant challenge for Democrats hoping to return to the 2012 days of lower educational polarization, thanks largely to strong pro-Democratic unions and much lower salience of racial *attitudes* and immigration policy. Do we think they really make up enough ground to meaningfully revert us to a late aughts/early-10s political environment? Especially now, when group identities are much stronger and parties have become significantly more sorted geographically — due only in part from education polarization.

My newsletter tomorrow will deal with these issues that “group-based democracy” (in political science terminology) pose to message- and strategy-driven models of campaigning. For now, let’s talk about the forecasting behind this work.

II. What forecasting really teaches us

There was substantial debate among less empirical political journalists yesterday (when Klein’s article went live) over whether we can really learn from these models, or whether they will fall apart in a short time horizon, rendering a discussion of their longer-term implications moot. For example, Benjy Sarlin, a policy reporter for NBC News, told me: “To try and speculate past even one election cycle, the most important piece of info you'd need is whether the president is successful and popular and that's the most impossible info to obtain.”

I don’t think this is right. For one, the most important “piece of information” you’d want is how the country voted last time. That’s because vote shares over time are relatively stable, mean-reverting processes.

But Sarlin’s comments also suggests to me that many people don’t really know what Shor is, and to a lesser extent I am, doing when we extrapolate trends into the future and say that Democrats are going to face huge deficits in the Senate for the next ten years unless something big changes. The meaningful difference between that and Sarlin’s forecasting — which seems to center on predicting vote shares for races years in the future — is that we are talking simultaneously about relative disadvantages in the Senate that are anchored to some stipulated range of national performances and correlated to long-term demographic trends that are likelier to continue than not, and about the aggregate implications of individual voting behavior which is much stabler than people think. In other words, (1) our written implications for Senate control are conditioned on broader trends continuing within some reasonable margin of error, which is highly likely, and (2) election outcomes in given states are constrained within a rough range — 4 points or so usually — of how they voted last time around.

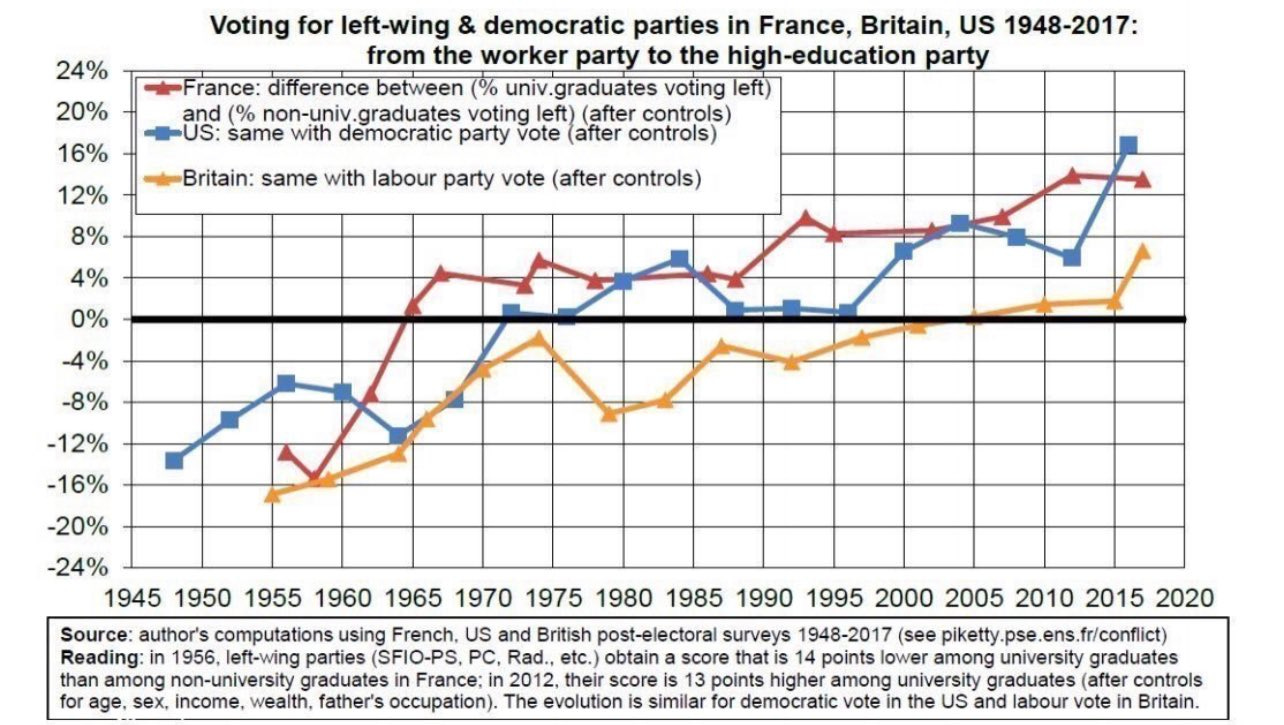

One thing that really bugs me is the disregard for history here. Below is a graph of education polarization in western democracies over the last 50 years. Sure, education polarization could decrease, but I think it’s unreasonable to expect a reversion here!

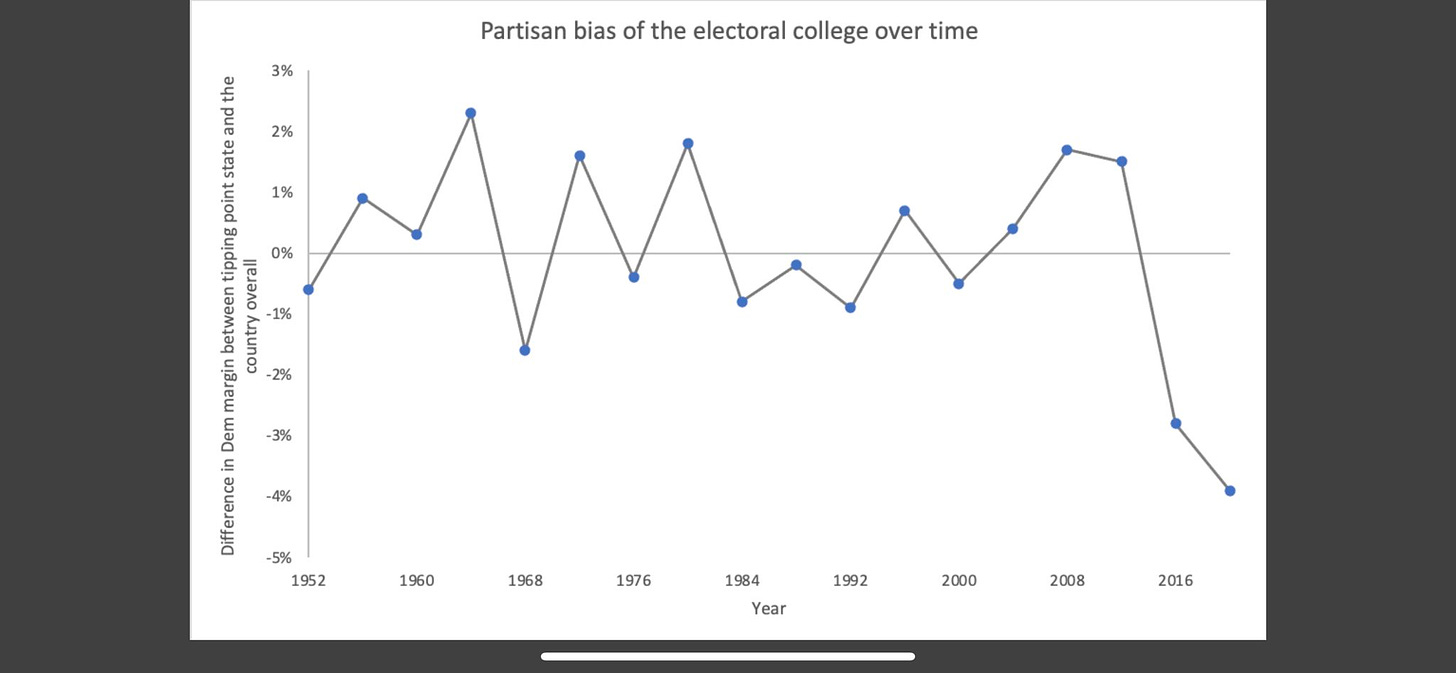

Another point is that we’re not really concerned about binary outcomes — whether Democrats can manage Senate victories or not — but the extent to which they continue to be disadvantages and the likelihood that the disadvantage grows. We are not forecasting point-estimates of election outcomes, in other words, but ranges of outcomes relative to some standard of fairness — in this case, 50-50 Senate control in a tied popular vote year. Because we’re looking at ranges and anchoring to long-term trends and reasonably competitive elections, these forecasts also aren’t invalidated by small deviations in those trends that some are stipulating.

Sarlin said in response to all this that “When people pronounced R’s dead [in 2018], my case was also that parties always respond to demographic hurdles and regroup, there are no permanent majorities.” And while this is true, it misses the point that education polarization and the pro-Republican bias in the Senate increased from 2018 to 2020, as predicted!

I think Sarlin’s final comment is really emblematic of the broader conventional wisdom failing to understand the methods, operationalization, and purpose here. Of *course* majorities could change! In fact, they probably will. But Shor’s math is meant to show that even extraordinary large shifts in educational polarization — such as a return to the politics of a decade ago — still leave the Democrats institutionally disadvantaged in the Senate, perhaps even prevented from winning a majority. And the likeliest scenario, that trends continue, almost dooms them at any decrease in their implied national popular vote.

There is a final rebuttal to Sarlin et al, which Klein added to my thread on Twitter:

Also, the point of this kind of model is to force a confrontation with a likely future, *and thereby inspire people to change it.* It's a mechanism for forcing people to reckon with trends they may otherwise ignore.

If the model serves its purpose, it won't come true.

Indeed. The real normative utility of forecasting models like these lies in what the model tells us about our elections and institutions conditional on some set of dynamics, not just in the predictions themselves. To sharpen the sword a little: The fact that the various predictors of individuals’ votes might change enough over the next 10 years to dig Democrats out of their structural hole, rendering the model errant, does not make the implications for those biases on democratic theory any less severe — and it’s likelier than not that things will get worse, not better, given that cross-country trend highlighted above.

I think pundits like Sarlin (and others; I’m not trying to pick on him!) also risk missing the forest for the trees a bit. Sure, there is uncertainty in our projections, but the fact is if Republicans continue to maintain even a 3-4 point structural advantage in the Senate, the downstream consequences of policy mismatch will be enormous — and that’s if you cut the advantage they have today in half! Implying that we don’t need to take the discussions seriously or debate reform because our math today might be wrong 10 years from now is a very unserious primary take if you truly care about representation and democratic outcomes.

And with that, my concluding remark is that pundits really need to read more theory and empirical political science research, and spend less time on Twitter. I can’t imagine anything less meaningful than making the electoral horse race into a social media horse race itself.

Thanks for reading today. If you have any comments, I would welcome the opportunity to read them in the comments below, or via email. You know the drill.

—Elliott

Alexander is the goods. We are in a period of becoming `stans. We have moved to a Democristan. We might have to move to another country. . .