Vladimir Putin, Russia, and public opinion in times of war | No. 185 – February 27, 2022

The Russian people do not appear to support Putin's war to occupy Ukraine

In 1942, George Gallup — still fresh in his transformation from an advertising researcher in New York to a political pollster — gave an address to the American Philosophical Society titled “How Important is Public Opinion In Time of War?”

“The arguments against public opinion polling in such a period have been recited often,” Gallup wrote. “The citizens of a country know little about military strategy… they know little about military needs… they do not appreciate the complexity of problems of organizing man power and natural resources. What is to be gained, therefore, in listening to their views on society?”

Gallup objected. Based on polls his company, the American Institute of Public Opinion (AIPO), had been conducting since 1935, Gallup asserted he could “answer the question of whether public opinion should be listened to as eagerly in time of war as in time of peace.” He listed off the apparent victories for the public, each underlining his broader point that a majority of the public had decided on actions Congress would end up taking months-to-years before they actually did.

A 1935 poll showed 70% of Americans wanted to increase military spending and 80% wanted to build up the Air Force.

A March 1939 poll found a majority of Americans wanted to lift the embargo provisions of the Neutrality Act and send supplies to US allies. Congress only did that in October.

A poll also found Americans wanted to send greater aid to Britain than the Lend-Lease Act of 1941 authorized.

And 82% of Americans in an October 1940 poll, 3 years after Japan invaded China, thought the US should freeze the shipment of war supplies to the Empire of Japan. Congress eventually froze this aid, but not until the middle of 1941.

Still, Gallup admitted, “It would be folly to assume that the people are always right at all times and places.” He said the public opinion only be trusted if it had an informed basis in reality, and was usually better on the broad direction of policy than on more specific matters.

Gallup thought journalists bore the brunt of this responsibility to educate the common person: “To be intelligent,” he wrote, “public opinion must be based upon facts—the facts which only a free press can give the people.” He asserted that England was “asleep” at the wheel from 1933 to 1937 because the free press kept from voters the true scale of Germany’s military buildup; and said, similarly, that France fell to Germany so quickly because the government would not listen to its people. “Public opinion can’t be blamed when it has no opportunity to help guide the destiny of a nation,” he wrote.

This is all well and good, and it certainly fits with democracy’s mandate of a sovereign people, but what Gallup didn’t take into account about wartime opinion was the power of the US government’s propaganda machine. To Gallup, as long as the press was writing about the war fairly, exposing the actions of the US and foreign governments for the average American, then their opinions could be trusted. But there is reason enough to think the process which generated those opinions was not as organic and fair as Gallup thought. Facts can be exaggerated, headlines influenced, and opinions shaped by messaging from the government. And that is especially true during wartime, not less true.

In a 2001 book called Cautious Crusade: Franklin D. Roosevelt, American Public Opinion, and the War against Nazi Germany, historian Steven Casey shows how Franklin Roosevelt deployed anti-Germany messaging to jolt the public out of its pre-war attitudes of isolationism and “America First.” Via the newly formed Office of War Information and the War, Navy and State Department, Casey alleges FDR “continually focused on the ideological threat posed by nazism,” though he “persistently refused to indict the entire German nation even after he became privately convinced that the mass of Germans were little better than their Nazi masters.”

This propaganda machine may have been good for preparing the people for war without “whipping them into a frenzy,” to use Casey’s words. And, as Gallup says, perhaps the public was right on many issues. But it also made some large errors of history and morality. For example, if FDR’s Office of War Information tried to contain mass vilification of Germans, it did not do so for hatred of the Japanese. One 1942 poll from the AIPO found that 48% of the public believed the Japanese-Americans forcibly moved to internment camps for the war should remain there indefinitely. (35% said they should be allowed to return home.)

This is all to say that Gallup appears to underestimate the severity with which the public opinion can be led away from what is a “right” and “rational” processing of the world around them. The US government and press in general routinely justified the internment of American citizens during the war purely because of their race. That is not a policy that was corrected by a free press, but which was exacerbated by it.

So, we can safely assert that wars should not be guided solely by the opinions of the common person — in America or abroad. But Roosevelt was still likely right to interpret his pledge to uphold America’s Constitutional democracy by listening in part to what the people wanted (at least when he agreed with it). If political leaders and the press are doing their jobs correctly, the average member of the public should be no more or less suited to inform government policy on the average issue (of course, not all of them!) than the average Congressional representative. Of course, that is a big “if.”

(PS: You can read more on how FDR used public opinion to advance his New Deal programs here.)

Public opinion about wars today

And that brings me to the obvious subject for this week’s newsletter: Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. I’ll ask the question Gallup did in his 1942 address: To what extent should democracies be guided by public opinion in times of war?

Based on our brief recap of the above studies on public opinion during War War II, we ought to assert that Russia, which purports to be a democracy — but is actually closer to an authoritarian regime, according to most scoring systems — should act in accordance with the rough shape of its public’s opinions.

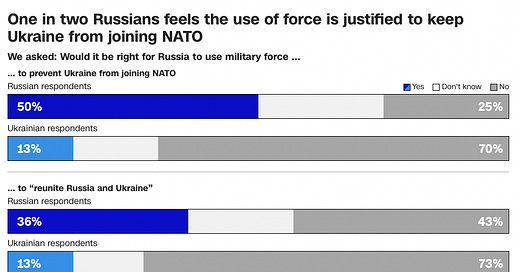

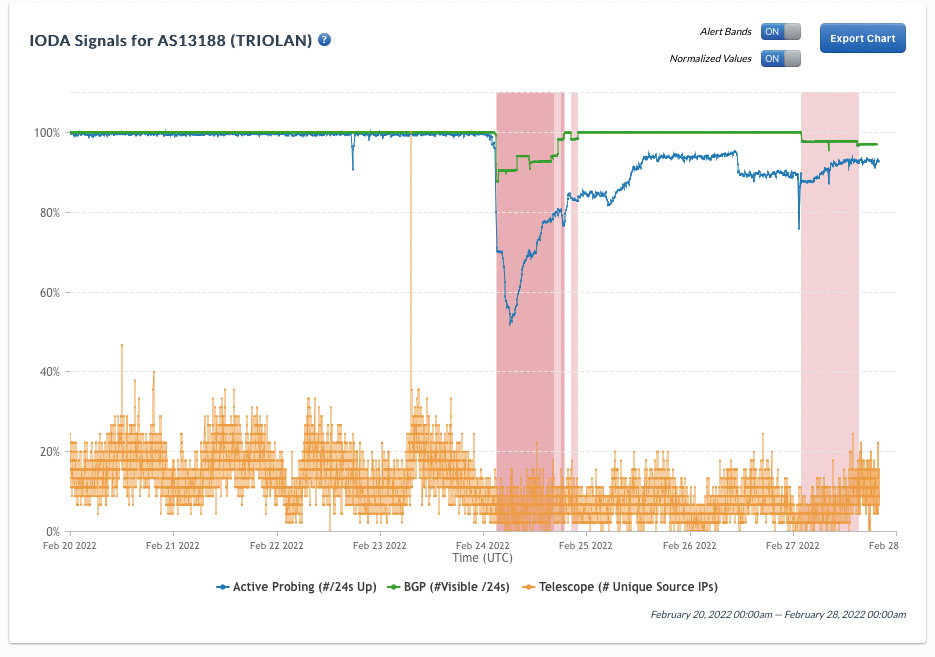

But as we talked about in yesterday’s subscribers-only thread, there are few reasons to believe Vladimir Putin’s actions represent the will of a majority of Russians. The country’s political system gives a huge advantage to United Russia, Putin’s party, in the State Duma (the national legislature) and gives de-facto dictatorial powers to Putin. But polls show few Russians want their government to take full possession of Ukraine, and only a bare majority favored invading the country to prevent it from joining NATO.

When I wrote about this yesterday, many subscribers asked whether Putin really cares about public opinion at all. I doubt he does. But pointing out the public’s demands is crucial to advancing a democratic mandate for governments globally, regardless of what we think executives “actually” care about. And, as history has shown, it can sometimes even be quite astute.

Posts for subscribers

If you liked this post, please share it — and consider a paid subscription to read additional posts on voter behavior, public opinion polling, and democracy.

Subscribers received two extra posts over the last week:

A series of charts on Russia war against Ukraine

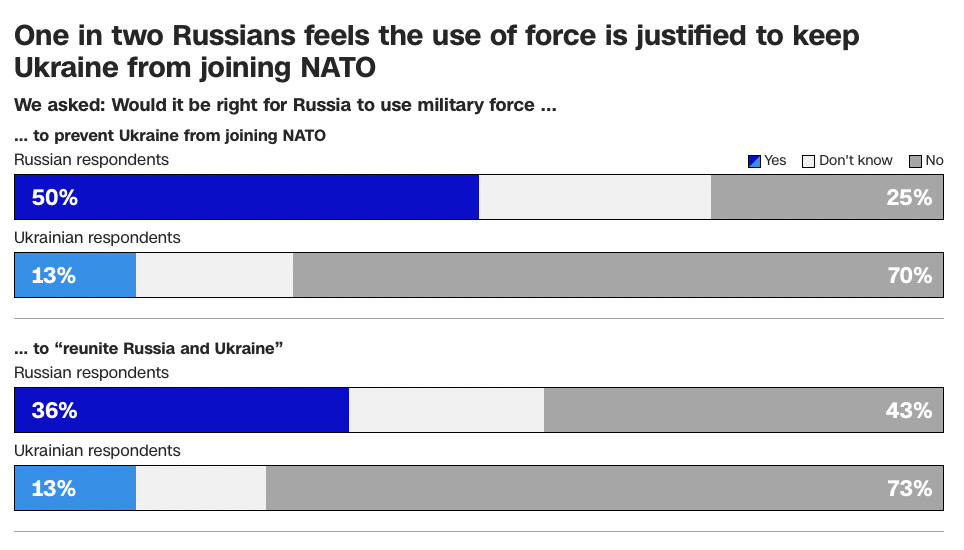

First, there’s the obvious chart about air travel being diverted away from Ukraine and the Russian side of the border:

My colleagues at The Economist also did a pretty good version (with a very nice title):

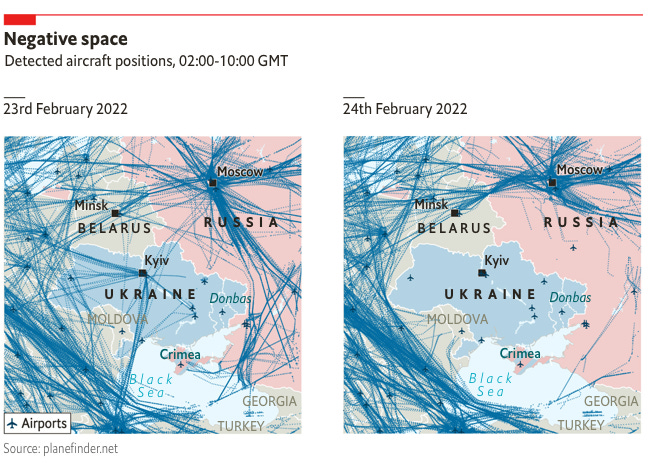

There have also been widespread internet outages across Ukraine. This screenshot comes from the Internet Outage Detection and Analysis (IODA) project at Georgia Tech:

And here’s another more legible version from my colleagues at The Economist (though it doesn’t have the latest numbers).

Finally, the Times also has an impressive set of maps showing the balance of territorial control as of February 26th:

Of course, while maps and data can do a lot of good storytelling about the war, nothing quite matches the impact of photos from the ground — much of which is extremely sad and heart-wrenching.

That’s it for this week. Thanks very much for reading. If you have any feedback, you can reach me at this address (or just respond directly to this email if you’re reading in your inbox). And if you’ve read this far please consider a paid subscription to support the blog.