The Trump effect on Americans' attitudes towards Vladimir Putin has mostly worn off

Donald Trump's 2016 presidential campaign raised GOP favorability of Putin. But nearly 80% of Republicans, up from 50%, now say Russia is our enemy

A bipartisan group of Senators last month promised to pass a bill constituting the “mother of all sanctions” against Russia for its aggression against Ukraine. Yet the parties couldn’t agree on what form those sanctions should actually take. Republicans wanted to sanction Nord Stream 2, a Russian gas pipeline in the final stages of construction in Germany. But Democrats argued that imposing such measures before an invasion would give up leverage that the US might need in diplomatic talks with Vladimir Putin. So Democrats attempted a bipartisan solution while tiptoeing around the Treasury Department, which prefers cutting off Russian access to funds stored in the US financial system.

When that dragged on, Republicans announced a bill that would give $500m to Ukraine’s military — which pissed off the Democrats working on the sanctions bill. And so, as of writing, no Congressional sanctions have been passed.

The drama in Congress is being used by the commentariat as proof that the partisan divide over feelings towards Russia is blocking an adequate response to Putin’s aggression. But while it’s true that there is a divide between partisans over how they feel about Russia’s leader, it is smaller than it used to be — and the vast majority of Republicans remain opposed to him and his country’s actions in Ukraine.

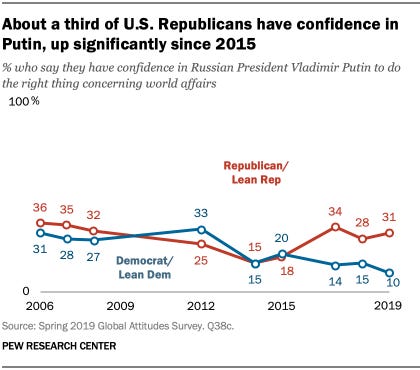

Consider these polls from the Pew Research Center. Pew has been asking Americans whether they have confidence in “Russian President Vladimir Putin to do the right thing concerning world affairs” almost every year since 2006, when he was in the middle of his second term.

After the parties’ opinions were tracking closely for a decade, Pew’s data show a spike in Republican confidence in Putin between 2015 and 2017. The share saying the believed he would do what was right for the world nearly doubled, from 18% to 34%. Meanwhile, Democratic confidence in Putin fell from 20 to 14 percent.

Pew data show clear evidence of a “Trump effect” in Republican attitudes towards Russia. And that is no surprise; partisans tend to follow the directions of the elites they align with. But how have things changed since then? The last poll in Pew’s graph was fielded in from 2019.

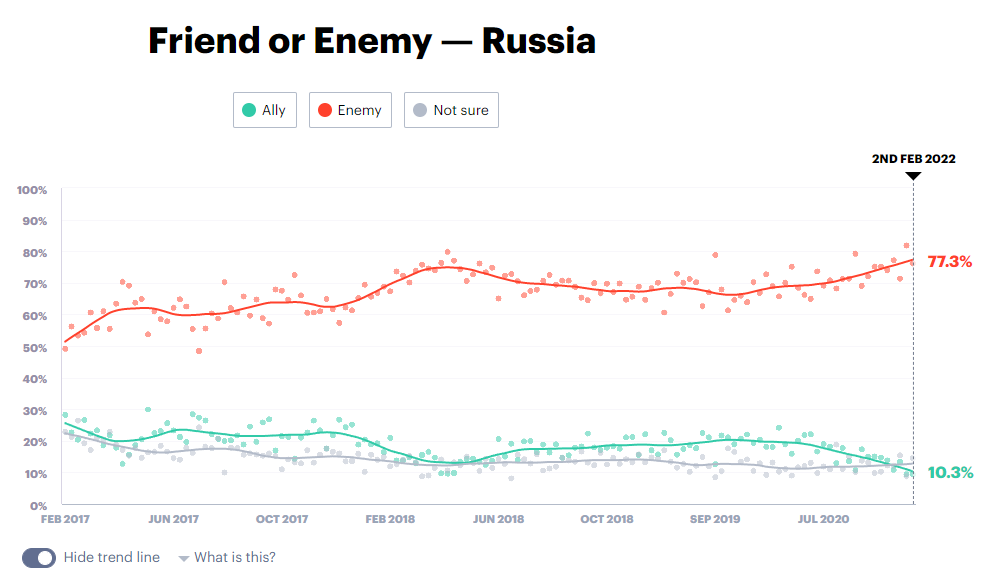

Looking at polling from YouGov, at the same time as Trump was taking office, about 60% of Americans overall were saying Russia was our enemy. A little under 20% said the country was our ally:

But there are some serious differences by party. The share of Democrats saying Russia is our enemy has increased from 70 to 81% between February 2017 and February 2022:

Republicans, on the other hand, started the Trump presidency with only 50% saying Russia was our enemy. A fourth (25%) said it was America’s friend:

Note, however, that opinions among Republicans have shifted dramatically towards those of the Democrats, and the population as a whole. Three in every four Americans who align themselves with the GOP now say Russia is our enemy, with only 10% saying they are our friend. (That is within the margin of error of the 8% of Democrats saying Russia is our friend.)

This agreement goes beyond asking the simple ally-or-enemy question. A January poll from YouGov, for example, found that 61% of Republicans said Putin posed a "serious threat" to the US. Only 5% said they sympathized with Russia in their conflict with Ukraine (57% said they sympathized with Ukraine). And 45% said Ukraine should be allowed to join NATO (13% said no). Along with 65% of Democrats, 52% of Republicans said the US should impose sanctions on Russia.

. . .

After looking at updated polling data, Republicans and Democrats actually look to be pretty close to lock-step on Russia, at least at the mass level. And even while there are some differences between them, a majority of members in both parties favors the same general approach to dealing with Putin.

This implies that, instead of being caused by real partisan differences in constituent preferences, Congress’s difficulty to pass sanctions on Russia looks to be caused either by a partisan divide that is only present only among elites and government leaders, or simply by typical idiosyncratic disagreements over how to do foreign policy. Or maybe it’s a bit of both. But it’s definitely not extreme polarization in voters’ desired policies.