How white racism and anti-democracy elite rhetoric create the conditions for right-wing violence | #196 – May 15, 2022

Research paints a picture of a republic frayed by the politics of white grievance and violent rhetoric by far-right politicians

When I blogged last week about how America’s counter-majoritarian electoral institutions and minoritarian politicking have insulated the Republicans from accountability and enabled, eg, the overturning of Roe v Wade, the stakes of the discussion hinged on two likely outcomes. The first is, obviously, the loss of abortion rights for women who want abortions. The second is the violation of the modern democratic principle of our social contract: the dual guarantees that everyone’s voice matters equally in determining who wins elections and that the majority gets most of what they want, most of the time.

This week, the stakes look even higher. When a man walked into a grocery store in a predominantly black neighborhood of Buffalo, New York yesterday and shot 13 people, killing 10, he illustrated the extreme consequences of the same minoritarian, anti-democracy thinking that is used to justify things like ending Roe and the existence of the US Senate, which primarily serves today as a blockade of any policy not favored by the numerical minority of white, rural Americans who control the 40 votes necessary to filibuster any bill proposed by the majority.

To be clear, I am not saying that all Republicans believe in the racist “great replacement theory” that pushed the Buffalo shooter to kill black Americans, who he viewed as political enemies. What I am saying is that the Buffalo shooting — and other terrorist attacks like it, including in El Paso, Texas, Charlottesville, Virginia, and Charlotte, North Carolina — is the product of people taking the predominant ideologies of America’s right today to their natural, violent extreme. And I want to share the social science that shows, empirically, how these things are tied together.

To get there, we have to look at a few things first. We will identify the major correlates of support for right-wing politicians in America today. We will see how those traits also predict anti-democracy and authoritarian attitudes. Then, we will see how both combine to increase the likelihood of a person engaging in partisan violence.

I. Why do people support the right?

I want to start this section by acknowledging that I am not going to be able to provide a comprehensive answer to the question “why are people Republicans.” There is not enough space in the newsletter — in fact, most email providers limit the size of any posts so there is a natural stopping point for me somewhere around 3,000 words and 5 charts. I am going to try not to write that long. Anyway. That means the question I’m really going to be answering is “why did people support Donald Trump in 2016 and beyond.” That is primarily because (a) he is the leader of America’s right-leaning party today and (b) we have really good survey-based social science research that provides a few answers.

The big study on this question is from Diana Mutz, a political scientist at the University of Pennsylvania. Her study “Status threat, not economic hardship, explains the 2016 presidential vote” looks at how people participating in a panel survey in 2012 and 2016 voted in each year and identifies variables that predicted their behavior. Mutz tested two hypotheses: The first was whether voters who were “left behind” economically from 2012 to 2016 were likelier than others to support Trump, all else being equal. The second was whether Trump drew more support among voters who ranked higher on a set of questions measuring so-called group “status threat,” or whether people (white people in particular) felt threatened by the rising statuses (incomes and cultural strength, primarily) of other groups.

Mutz writes:

Contrary to conventional wisdom, there is little to no evidence that those whose incomes declined or whose incomes increased to a lesser extent than others’ incomes were more likely to support Trump. Even change in subjective assessment of one’s own personal financial situation had no discernible impact on evaluations of Trump or on change in vote choice. Likewise, those who lost a job between 2012 and 2016 were no more likely to support Trump. [The results] further suggest that change over time in the extent to which a person perceived that trade had influenced his or her family financial situation made no difference to candidate attitudes or preferences.

… Changes over time in indicators tied to racial/global status threat were far more influential as predictors of change toward greater Republican thermometer advantage and as predictors of greater likelihood of Republican vote choice. ][Increases] in SDO significantly predicted changes in Republican vote choice as well as Republican thermometer advantage. When a person’s desire for group dominance increased from 2012 to 2016, so did the probability of defecting to Trump. However, as shown by the insignificant interaction between SDO and wave in both analyses, there is no evidence that those high in preexisting SDO were especially likely to defect to Trump, thus countering the idea that SDO was made more salient in 2016. Instead, it is the increase in SDO, which is indicative of status threat, that corresponded to increasing positivity toward Trump.

Mutz’s study shows how, in her words, “The 2016 election was a result of anxiety about dominant groups’ future status rather than a result of being overlooked in the past.” (NB: This sounds a lot like the rhetoric on “replacement theory” coming from the right today! But more on that later.)

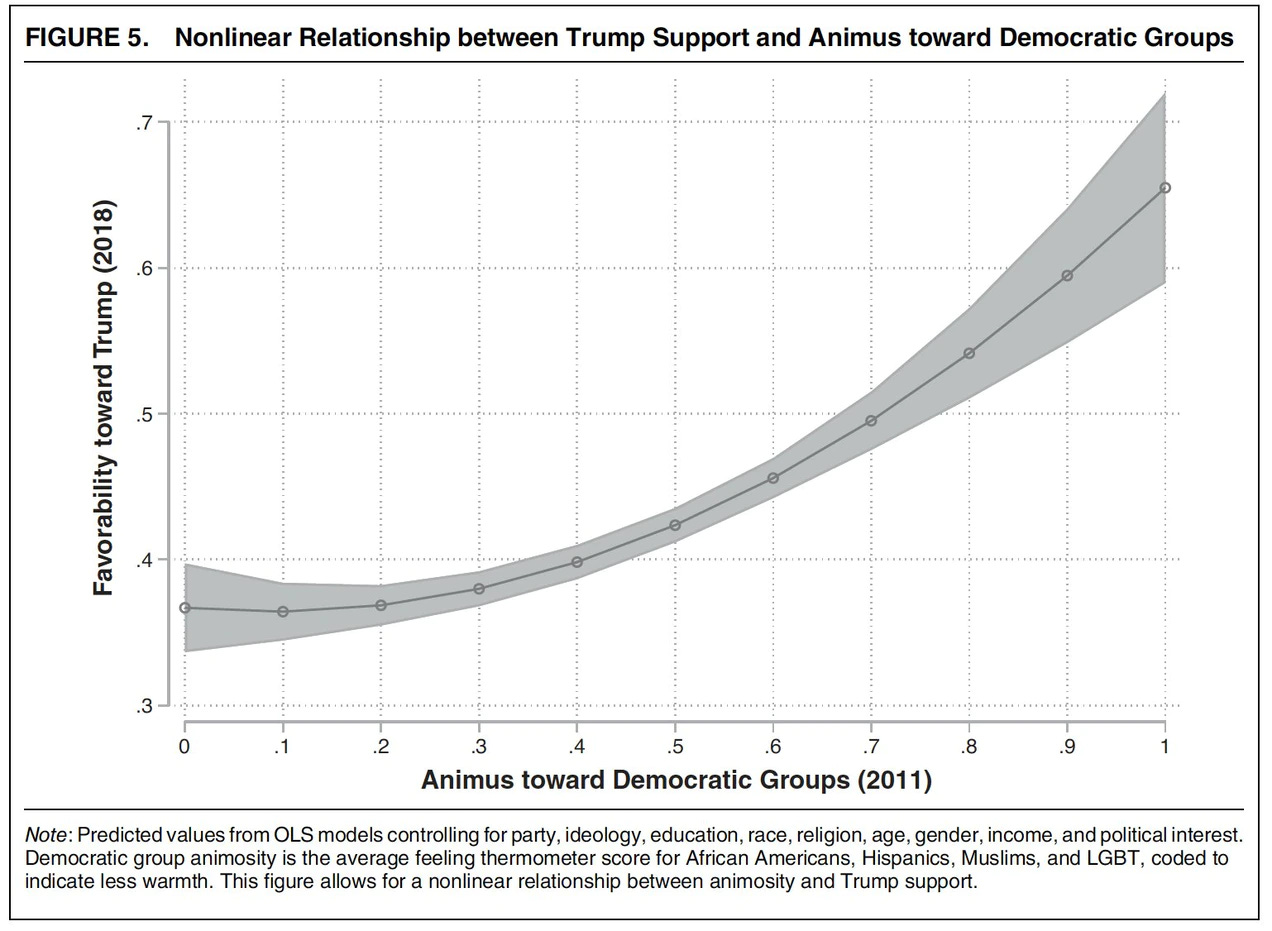

Mutz’s conclusion is echoed by another more recently-published study conducted by political scientists Lilliana Mason, Julie Wronski, and John Kane. They also look at respondents’ answers to questions about politics over time — specifically in 2011 and 2018. Back in 2011, they asked every respondent to rate African Americans, Hispanics, Muslims, and LGBT Americans on a “feeling thermometer” scale from 0 to 100 and then averaged them together, in effect creating an aggregate score of how warm or cold (or, perhaps, favorable or hostile) a person was to traditionally Democratic groups.

This variable was then used to predict how favorably someone rated Trump in 2018. The authors show the results of that predictive model in this graph:

In a Twitter thread about the study, Mason wrote:

This means that there is a faction in American politics that has moved from party to party, can be recruited from either party, and responds especially well to hatred of marginalized groups. They're not just Republicans or Democrats, they're a third faction that targets parties.

Their current control over the GOP makes it seem like a partisan issue. But this faction has been around longer than our current partisan divide. And calling it partisan is a misdirection (even if it is facially true).

It draws our attention away from the faction and forces us to "both-sides" democracy v. anti-democracy. These two sides are not equivalent. As academics and journalists, who are pressured into non-partisanship, it makes it difficult to speak honestly about the threat.

The evidence here shows that outright animus toward non-whites and non-Christians was a powerful motivator of support for Donald Trump in 2016. That’s even true for people who called themselves Democrats in 2011. These are the same Obama-to-Trump switchers that Mutz identifies as exhibiting high levels of status threat in 2012.

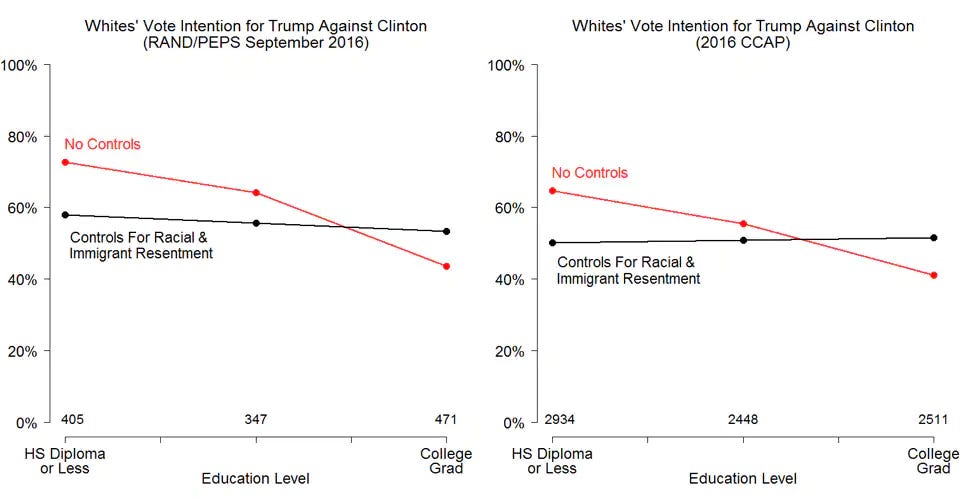

Now consider one last piece of analysis, from Michael Tesler, who teaches political science at the University of California, Irvine. He analyzed data shortly after the 2016 election and found that the apparent education divide in support for Donald Trump — with white voters who do not have a college degree being the likeliest to vote for him — was not driven by education, but instead by respondents’ views on several questions related to race. The large education divide in America disappears when you control for resentment toward immigrants and minorities, he wrote.

Here, it is important to note that the variable Tesler is measuring is not “status threat” or an average “feeling thermometer” score for minority groups. It is respondents’ scores on the “racial resentment” scale — a battery of survey questions social scientists invented to directly capture animus towards African Americans (and likely captures beliefs about other non-white groups too). Questions include whether a respondent agrees that “It's really a matter of some people just not trying hard enough: if blacks would only try harder they could be just as well off as whites” or “Most blacks who receive money from welfare programs could get along without it if they tried”.

This is all pretty robust evidence. And, of course, it affirms what we know from observing the real world: Donald Trump drew much of his success in 2016 from voters with high levels of animus towards voters who are traditionally aligned with Democrats. That includes black voters and immigrants, but also Muslims and LGBT Americans.

II. “Ethnic antagonism” erodes support for democracy

The social science evidence shows that these high levels of animus towards non-white, non-Christian Americans also predict lower levels of commitment to democracy, particularly among Republicans.

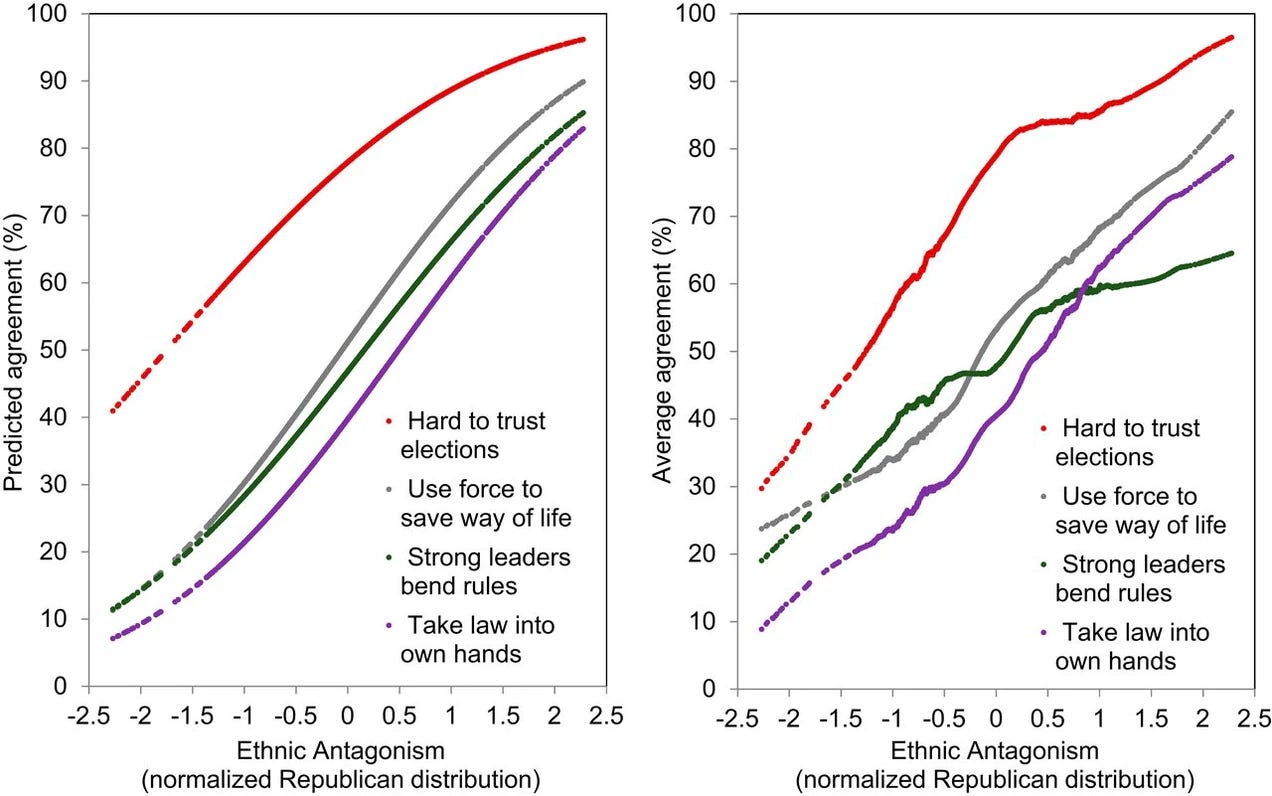

According to another study of survey respondents published by Vanderbilt political scientist Larry Bartels in September 2020, “ethnically antagonist” voters are also much likelier to agree with statements we traditionally view as authoritarian, such as “the traditional American way of life is disappearing so fast that we may have to use force to save it”, “strong leaders sometimes have to bend the rules to get things done”, and “it is hard to trust the results of elections when so many people will vote for anyone who offers a handout.” Here, Bartels plots the positive relationships between these two variables (ethnic antagonism and agreement with illiberal beliefs).

Breaking down the relationship between antagonism and support for different illiberal opinions, Bartels says::

holding other attitudes constant at average Republican values, the predicted probability of agreeing that “we may have to use force” to save “the traditional American way of life” increases from 0.226 at the 5th percentile of Republican ethnic antagonism (−1.43) to 0.813 at the 95th percentile (1.58). The corresponding increase in the predicted probability of agreeing that “patriotic Americans” will have to “take the law into their own hands,” holding other attitudes constant at average Republican values, is from 0.153 at the 5th percentile of Republican ethnic antagonism to 0.718 at the 95th percentile.

And as if he were peering two years into the future, Bartels writes that “the effects of millions of White Americans’ concerns regarding the prospect of demographic, social, and political change may not be limited to the electoral sphere.”

Many people who endorse resorting to force or taking the law into their own hands in the context of an opinion survey are unlikely to engage in actual violence or lawlessness. However, the United States has experienced a cataclysmic civil war and a long history of racial and ethnic violence, and currently experiences thousands of hate crimes per year; thus, it is not fanciful to suppose that expressive support for bending the rules or resorting to force to protect one’s “way of life” is consequential for actual behavior—or that it could become even more consequential under inflammatory circumstances.

Now, add this together with the finding in part one. The current statistical evidence suggests that voters who were more likely to rate non-white, Democratic-leaning groups as extremely cold on a feeling thermometer — what the social scientists doing the work called “animus” towards those groups — were both more likely to vote for Trump in 2016 (and probably 2020) and already held illiberal, anti-democracy tendencies before he lost the 2020 election.

By folding voters with high levels of racial animus into the GOP between 2012 and 2016, Donald Trump gave community and purpose to a unified group of voters who embraced “taking the law into [their] own hands” and "using force to save [their] way of life.”

That sounds a lot like the violence we saw in Buffalo yesterday. And it is a probable explanation for the attempted insurrection at the Capitol on January 6th, 2021.

But how much does the literature tell us about actual partisan violence going forward?

III. What causes partisan violence against opponents

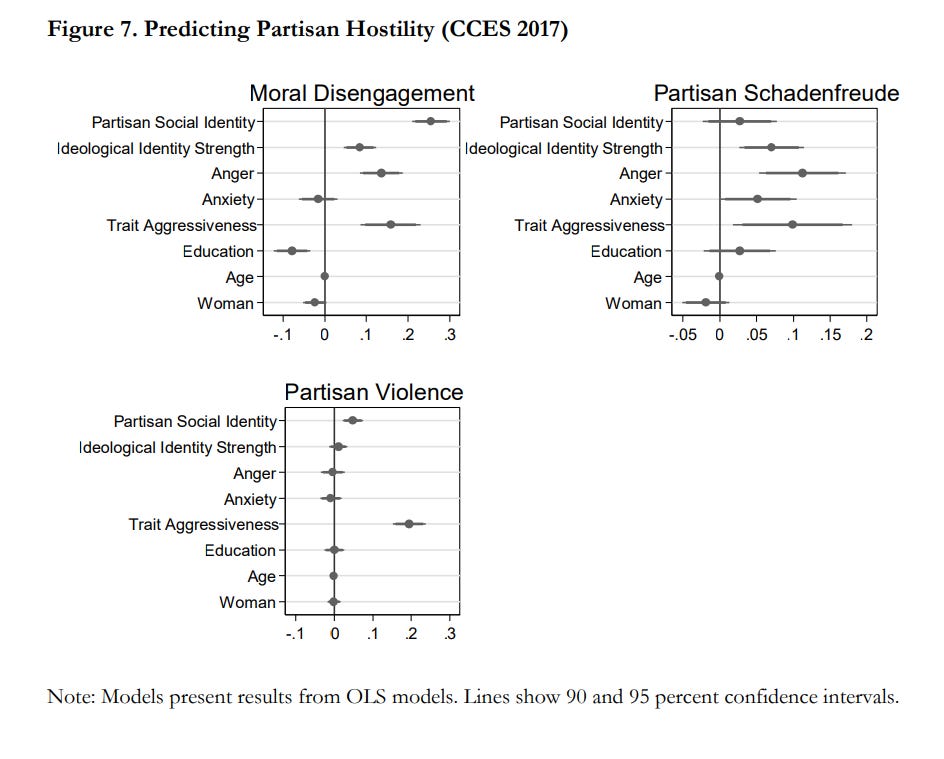

The social science literature today suggests a strong causal arrow pointing from strong partisan identity and feelings of aggression, on the one hand, to so-called “moral disengagement” that rationalizes harm against partisans and actual support for partisan violence, on the other. Political scientists Nathan Kalmoe and Lilliana Mason have done much of the recent work on the subject, measuring the concentration of what they call “lethal mass partisanship” among the public.

In a set of surveys from 2017 and 2018, Kalmoe and Mason measure how likely respondents were to agree with statements like whether they’d be okay if partisan opponents died of cancer and whether it is justified for their party to use violence to advance their political goals. (The actual wording is on page 17 here.)

They present this graph of their findings, which shows how strongly different traits or demographic attributes (on the vertical axis) correlate with partisan hostility (disengagement, schadenfreude, and violence) on the horizontal axis:

The results suggest that all else being equal, as the electorate continues to grow more strongly partisan moral disengagement and outright support for violence is likely to increase. In the authors’ words:

Ultimately, these results find a minority of partisans view violence as acceptable acts against their political opponents. Many times more embrace partisan moral disengagement, which makes the turn to violence easier if they have not made it already. As more Americans embrace strong partisanship, the prevalence of lethal partisanship is likely to grow.

Mason and Kalmoe also have a new book out on this subject. They give this dynamic of “Radical American Partisanship” an even more in-depth treatment, exploring (among other things) how leaders can inflame passions and lead partisans to violence in the name of their tribe and what reforms could help solve the issue.

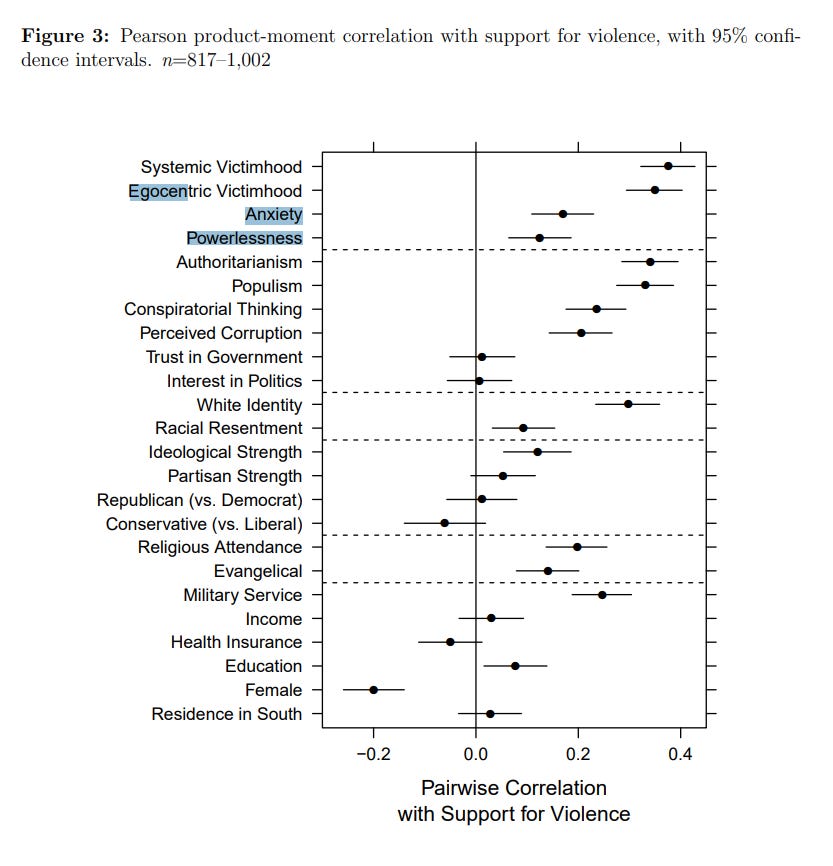

But for now, let’s go over one final study. In a forthcoming paper titled “Who Supports Political Violence?,” Political Science professors Miles Armaly and Adam Enders analyze the results of another survey and find that “perceived victimhood, authoritarianism, populism, and white identity are the most powerful predictors of support for violence.” Their study is notable for the number of social- and political-psychological variables they construct to control for various predictors of violence.

And here is the correlation between each trait and support for partisan violence:

Armaly and Enders run a separate analysis to assess what predicted Republicans’ support for the January 6 insurrection. Controlling for everything in a mess of regressions, they find that a person’s level of support for Trump and the strength of their partisan and ideological identities were the strongest predictors of voicing support for the riot.

While their results suggest that “neither Democrats nor Republicans, liberals nor conservatives appear to be asymmetrically supportive of political violence…. victimhood and authoritarian personalities are hardly marginal orientations among the American mass public, and politicians—like Donald Trump—have seemingly recognized some utility in activating these orientations, presumably to expand and mobilize their base.”

What do you do when people tell you you’re under attack?

So, how can we synthesize this all?

One way to tie it together is to say that by exploiting ethnic antagonism for electoral gains and tying white identity to Republican identity, Donald Trump and the GOP have caused a simultaneous erosion in support for democracy and increased the likelihood of scattered partisan violence in America. You do not have to look far to find examples of Republican candidates for office or far-right cable TV hosts or even Trump’s aids repeating the same racist “great replacement theory” that motivated the Buffalo shooter to kill 10 people yesterday. That has led to a large number of people, mostly Republicans, who believe in it — and will lead to an increase in episodes of partisan violence.

But it is worth remembering the broader context of the terrorism in Buffalo, too. The traits and attitudes that correlate with the justification of partisan violence are also tied to delegitimizing political opponents, and, from the right, multiracial majoritarian democracy itself. It’s how you get people saying we’re “a republic, not a democracy” and that “the real problem is that people vote too much” and that the people of Washington, DC are not “working class” enough to deserve political representation. It’s how you get Donald Trump saying mail ballots from cities are all illegal — presumably, he thinks, like the people who live there.

Right-wing commentators, thought leaders, and politicians have sold white racists on the lie that the Democratic Party is importing people from “third world” countries to alter the composition of the electorate and change the fabric of their society. To protect themselves, they must first commit to making sure Democrats do not win elections and allow open borders — where these people supposedly enter the country en masse. That means they should push for voter suppression laws and, if legally able, overturn the results of elections they view as illegitimate (or which produce an outcome they view as illegitimate). And when that doesn’t work and the invaders do win status, the loyal American must follow the directions from their leader and take up arms to protect their own — at any cost.

Synthesizing (1) anti-democracy and pro-violence rhetoric from far-right political candidates with (2) the social science evidence and (3) actual occasions of ideological violence in the real world, it is hard not to think we are on the brink of something worse. Potentially much worse.

Talk to you all next week.

Elliott

Posts for subscribers

If you found this post satisfactory, please share it — and consider a paid subscription to read additional posts on politics, public opinion, and democracy.

Subscribers received one extra post over the last week:

That’s it for this week. Thanks very much for reading. If you have any feedback, you can reach me at this address (or just respond directly to this email if you’re reading in your inbox). And if you’ve read this far please consider a paid subscription to support the blog.

Thank you for this analysis, Elliott. It was suspected but not previously verified. Two roads lie ahead. One requires a passport.