The problem with the Electoral College is not partisanship or urban-rural polarization

At least, not directly. The system itself creates many different opportunities for mismatches between the will of the people and the will of electors

This paper — which builds a series of mathematical models to analyze the probability of mismatches between the popular vote and Electoral College since the 1820s — recently showed up on the front page of Reddit. That is interesting because I wrote about it years ago! More important is that it’s a really interesting paper, too, with lots of lessons for people (like me!) who think about ways to make America’s electoral systems better.

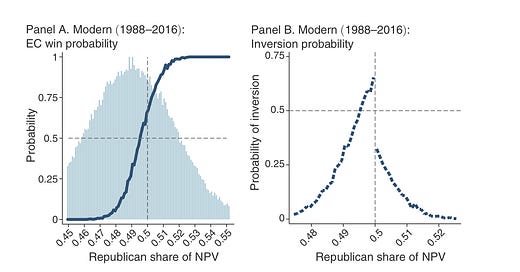

The professors and undergraduate researcher who performed the study are interviewed here on some of the main findings from it. The big one is that the chance a presidential candidate wins the Electoral College majority while losing the national popular vote is largely a function of national electoral competitiveness. Mismatches only happen in close contests, the authors find, so eras of close elections (like the one we have now) are particularly prone to mismatches — or, to use their term, “inversions” — in the outcome. This chart from their paper shows the percentage chance of an “inversion” in simulated elections from 1988 to 2016 as a function of the Republican Party’s vote share:

This is not so surprising on its own. Two of the last six presidential elections have had inversions; that’s an error rate of 33%! What’s really interesting about the paper is what it finds about the shape of partisan biases in the Electoral College system. Panel B of the graph above, for example, shows that inversions are much likelier when Republicans barely lose the national popular vote — like by 1 percentage points or less — and also much likelier than inversions that see Democrats elected. In fact they find that inversions are the likelier outcome in these close scenarios: in other words, since 1988, elections with slight Democratic popular vote leads have had higher modeled probabilities of being won by Republicans than Democrats. That’s because of the various pro-rural and small-state biases the authors uncover in presidential election results.

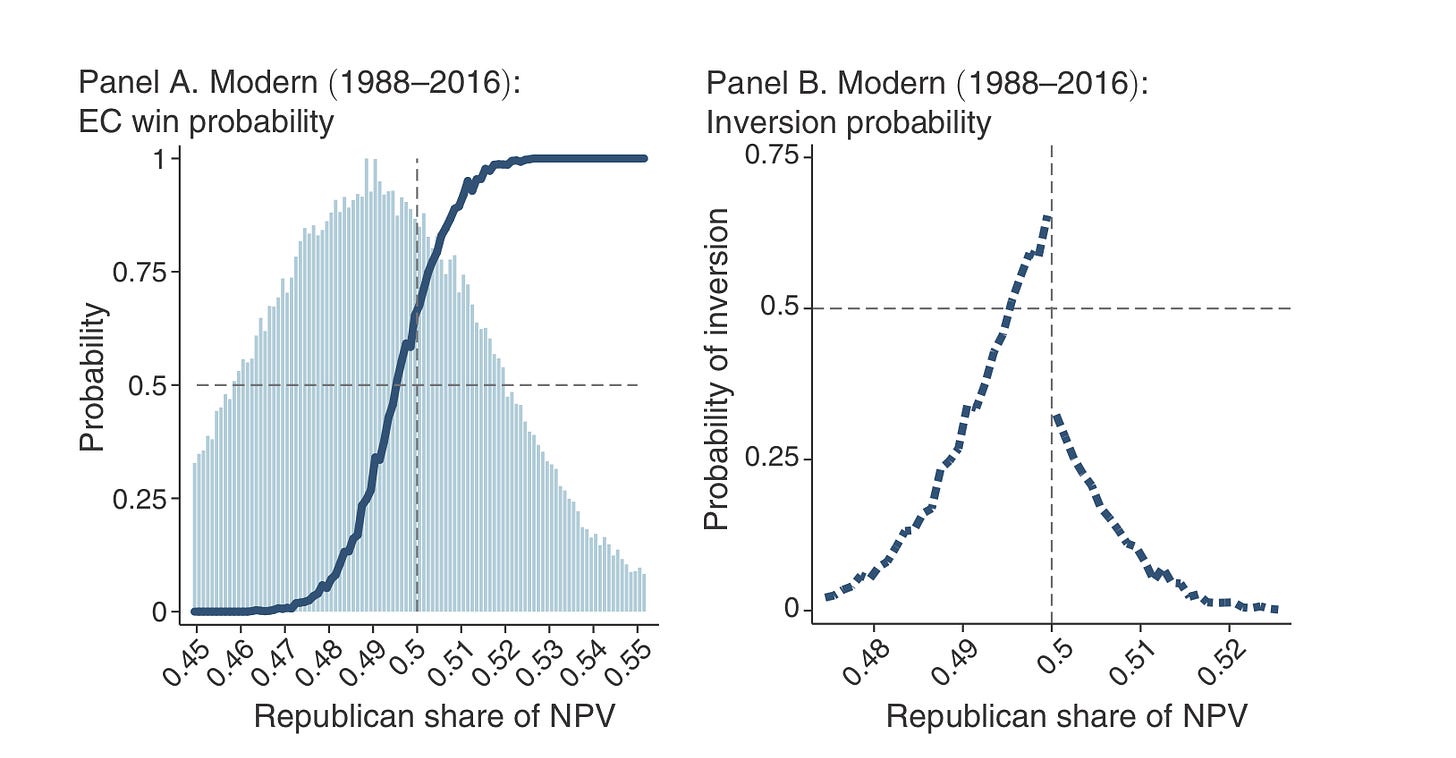

What is additionally novel about their study is that it looks at historical election results beyond the modern era. Most of our election forecasts stop in the 1970s or so, when access to high quality polling, demographic data, and state-level election results gets a little harder. But because they are only modeling state-level results directly they can push the time horizon back towards America’s findings. So, running the same models in the post-Reconstruction era (from 1872-188) as they did for modern elections, the authors find that states with more Republicans were then disadvantaged by the Electoral College. The authors suggest this is because Southern states, where Democrats were dominant, were apportioned electors based on the number of all residents of their states, but then denied Black Americans the right to vote — functionally increasing the ratio of electoral votes per vote in the South.

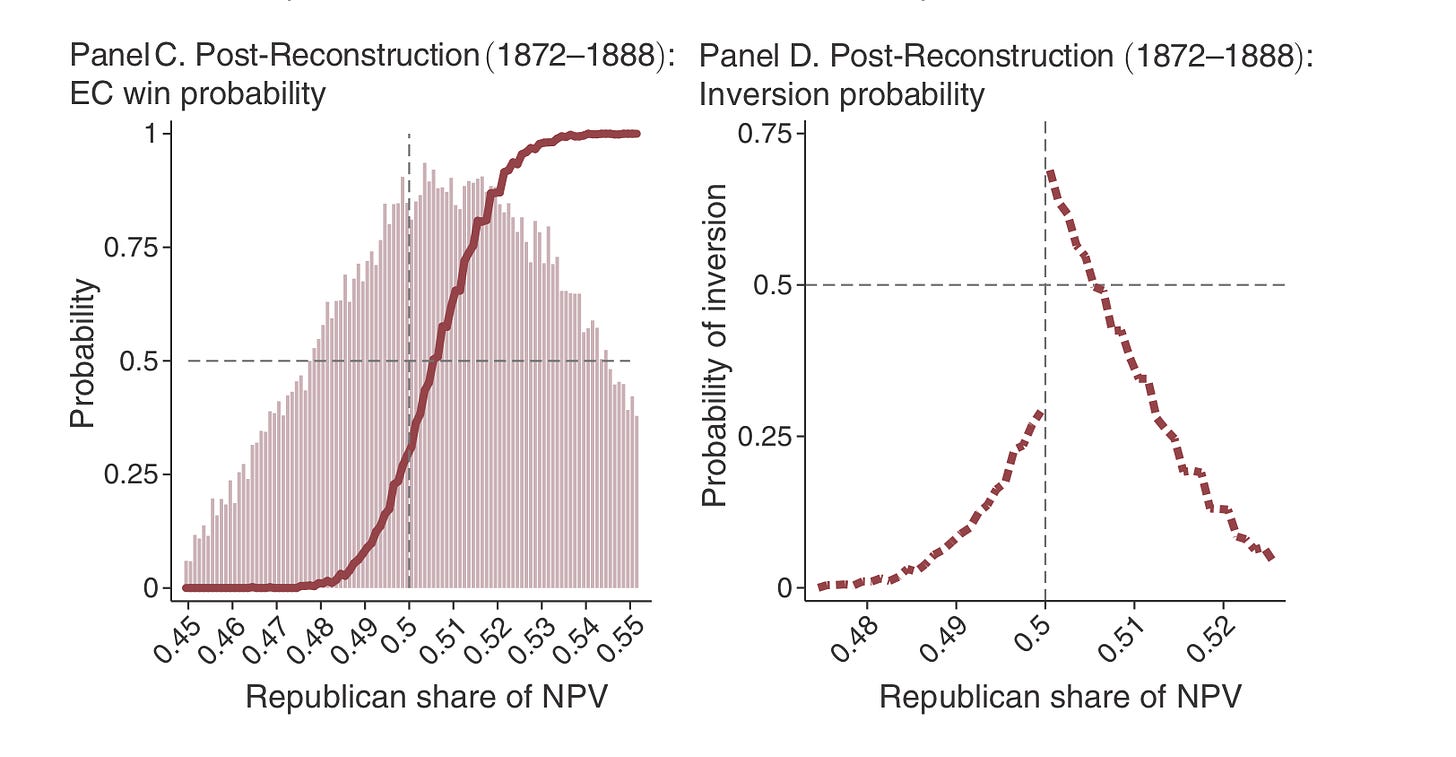

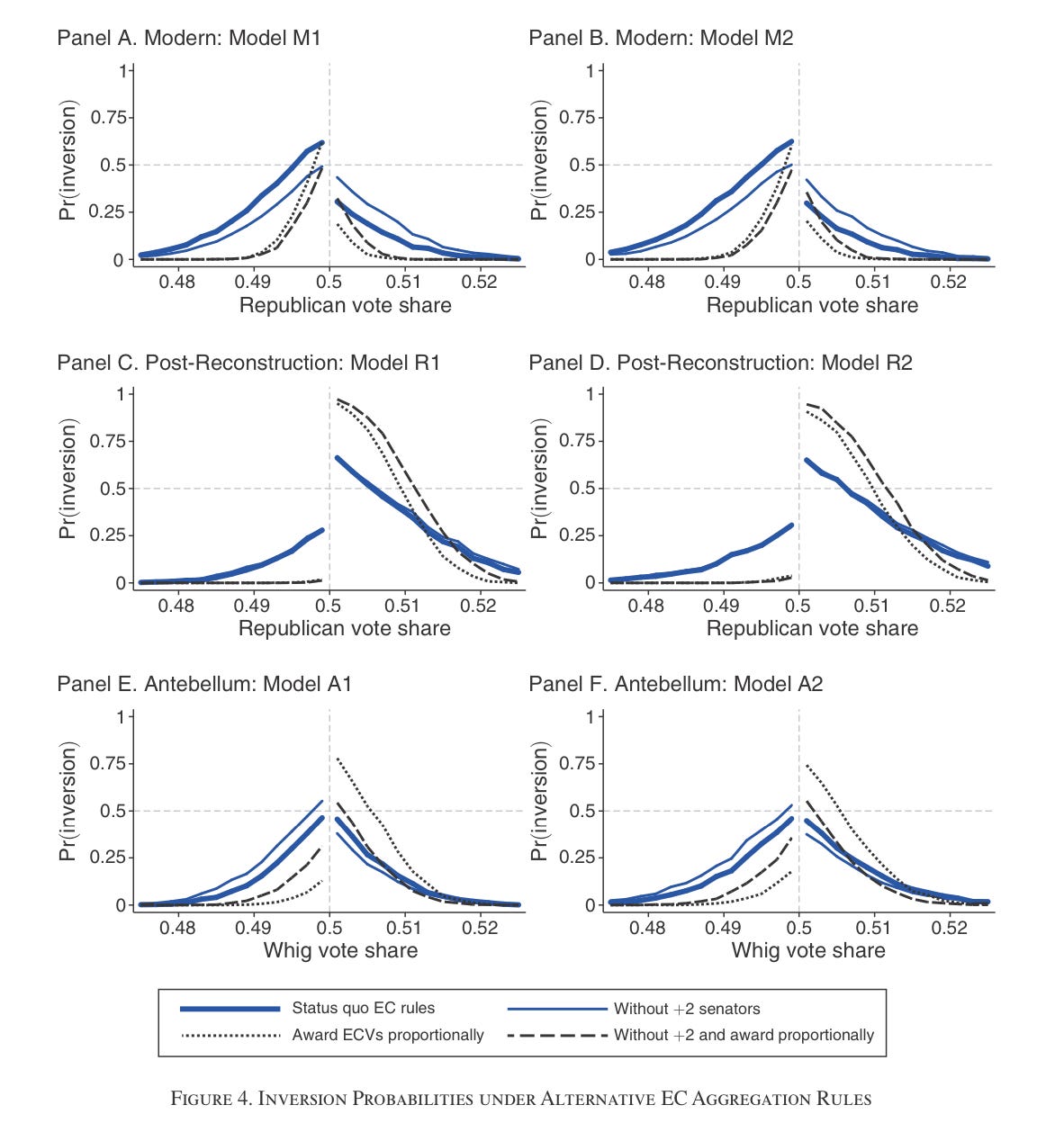

The paper wins extra cool points for exploring what these biases would look like under different allocation rules for electors. What would happen if electoral votes (EVs) were assigned proportionally to popular vote in every state, for example? What if the Senate didn’t exist, and EVs were assigned to each state proportionally to its population? The authors find that inversions would be less likely, but could still happen. This is especially interesting to me given the share of people who believe that proportional EV assignment would fix our problems.

This means that the precise rules America uses to assign electoral votes is not the problem. The problem is the existence of electors themselves

There are a few ways this plays out. One is that states are malapportioned; that smaller states get more of a say in who wins. So some people think that increasing the size of the House would eliminate most of the chance of inversions. But the researchers find that the probability of an EC-popular vote inversion in a race decided by less than one point nationwide drops by roughly ten percentage points, from 30% to 20%, if we double the size of the House of Representatives from 435 to 870. A 20% chance is still higher than 0 — so what are the residual causes?

Well, there is also heterogeneity in turnout — with whiter states having higher turnout — that means some states systematically get a higher say. There is no systemic fix for this problem, other than to stop voter suppression measures and encourage everyone to vote. That means this is not a problem with the Constitution per se, but how states have abused it.

Then, because the Electoral College divides the US population into smaller numbers, there is always going to be the potential for (what they call) “rounding errors” in who gets more of a say than someone else. But these are not so large; the ratio of House Representatives per person does not vary by more than a few thousand voters in most scenarios.

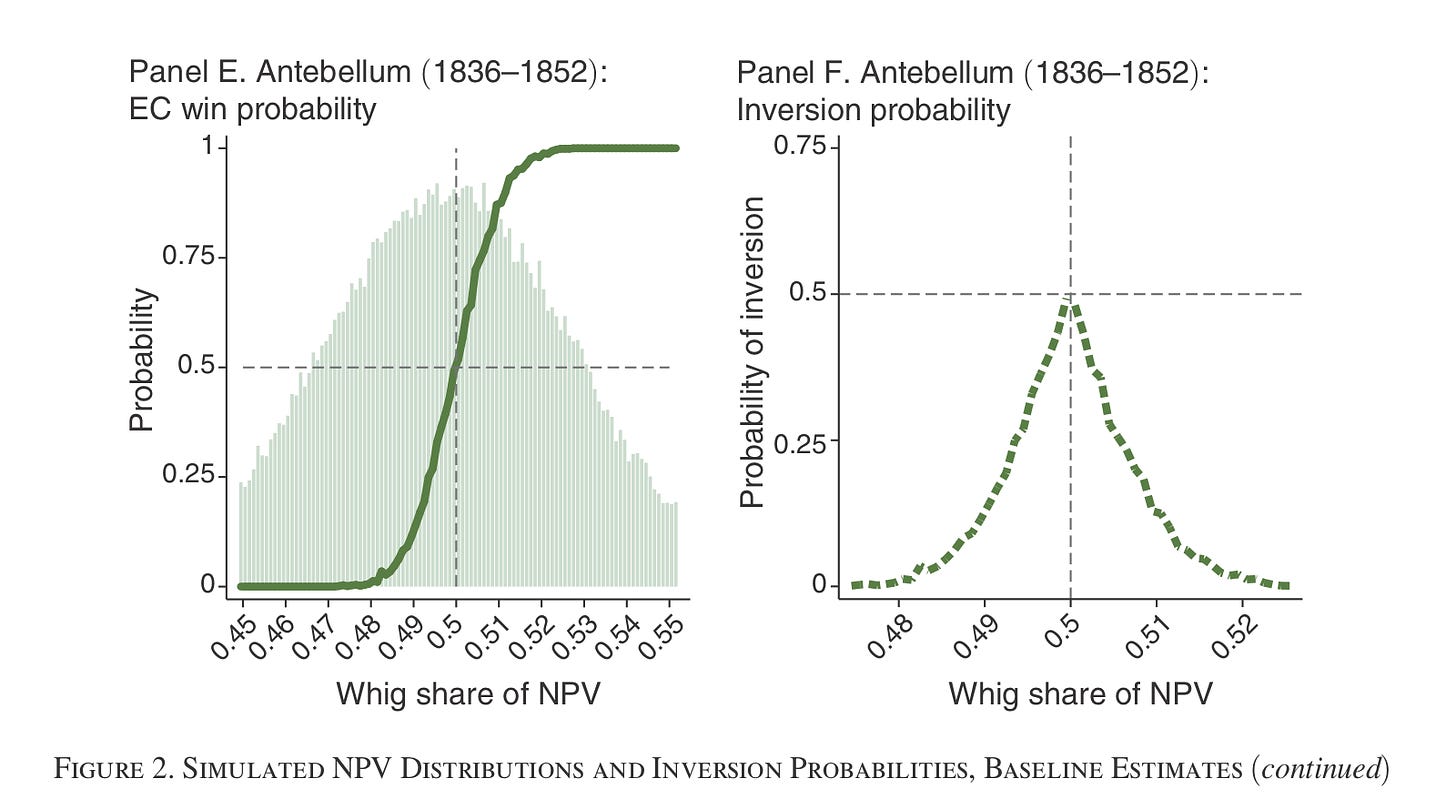

Now, all of these biases are not guaranteed to cause inversions in tandem. Indeed, the study finds they sometimes act as counterbalancing forces. During the Antebellum period, for example, there was no systematic bias towards either major party in who benefited from inversions. These numbers are actually remarkably equal

The problem with the Electoral College system happens when these factors start to advantage the same party. Today, smaller states are advantaged by the EC, and they all tend to vote for the same party. These states also tend to have lower turnout, further biasing the outcome.

In summary, the authors write, “there is no guarantee that any change to the Electoral College system short of implementing a national popular vote, will reduce the probability of inversion or of asymmetry… We conclude that electoral inversions are not statistical flukes but are enduringly fundamental to the US Electoral College system. No tweak of election rules short of moving to a national popular vote will prevent a chance of inversions in close elections.”

Of course, some of us have been saying this for a long time now. But I’m happy that the most comprehensive math I’ve seen yet reiterates these points. It also inspires hope that the young people on Reddit went crazy for it.

In a close contest, faith in an honest popular vote without the electoral college is naive. The only time (1876) we threw out electoral college votes was when there was evidence of massive vote fraud, only documented because of the present of federal troops as observers. To control election outcomes, violence and all forms of cheating have been used, especially when the stakes are high. To win with the present electoral college, you need to win closely contested large states, with maximum publicity, exposure and opposition. By contrast, stuffing the ballot is easiest in places where one party exerts complete control -- but this influence on the popular vote has little impact on the electoral college, which is why it is not much practiced in presidential elections. Your faith that elections would be honest contests without the electoral college is naive and ahistoric. Students of Black electoral history will know why I say this.

Nice work! The problems are money, propaganda, GOP philosophy, much like that of the Mongol hordes, how to get the rats out of the stable, and how to keep them out of the stable,