The problem at the heart of January 6th — and the future of American democracy

Democracy's opponents control enough votes to meaningfully roll back civil and electoral rights. It will take a generational shift in civic and democratic culture to defeat them.

I am sure you have been inundated with articles marking the first anniversary of the attempted coup on January 6th, 2021. But at the risk of sending you something too late (and also because if I wait any longer, I will have missed the news) I would like to offer my perspective on the broader significance of the events of that day. These observations are rooted in (what else?) political science, survey experiments on voter psychology, and other polling data. I think that makes them distinct from what you have probably read elsewhere, and therefore worth giving your attention to.

The way I see it, the basic problem facing American democracy is two-pronged. First, that a significant number of people do not want to extend basic political rights to their opponents — groups marked by their differences from white, Christain, and conservative Republican Americans. And, second, that this faction has united with ideologically similar groups under one massive political banner to create a threatening force of anti-democratic partisans.

The manifestations of these threats — in political violence, voter-suppression laws, partisan gerrymandering, and what have you — are all second-order to or exacerbate, the first problem.

For example, the various vulnerabilities in the process of transferring presidential power that were exposed on January 6th, 2021 stem from the fact that the faction is also not opposed to using violence in order to keep power. Similarly, the anti-democratic, counter-participatory rule changes we have observed in Republican-led states since January 6th show the faction will do everything in its legislative power to gain an electoral advantage over its opponents. Yet although it is obvious, it is worth stating that we would not have these issues without first having a group of people that supports them.

I do not mean to minimize these second-order issues, of course. I have written dozens of times about several things we may do to control their consequences. Better leadership from the political right is the best option, but also the least likely. Amending our electoral system, via something like ranked-choice voting or proportional representation, in an attempt to decouple the political right from this “MAGA faction,” could also do a lot to decrease the potential damage they might do to the country. And it is “easy” to legislative ourselves out of partisan gerrymandering; Congress needs “only” to enact federal standards for fair districts. (

Yet neither of those changes would fix the first-order issues.

But before we get to potential solutions, let me use the political science evidence to show you how we know this faction exists and why we think it is motivated by opposition to multiethnic, inclusive democracy. The following science is crucial to understanding what makes this group think — and to characterizing it not as a purely partisan group, but something that poses a more insidious risk to democracy.

I. Democracy for me but not for thee

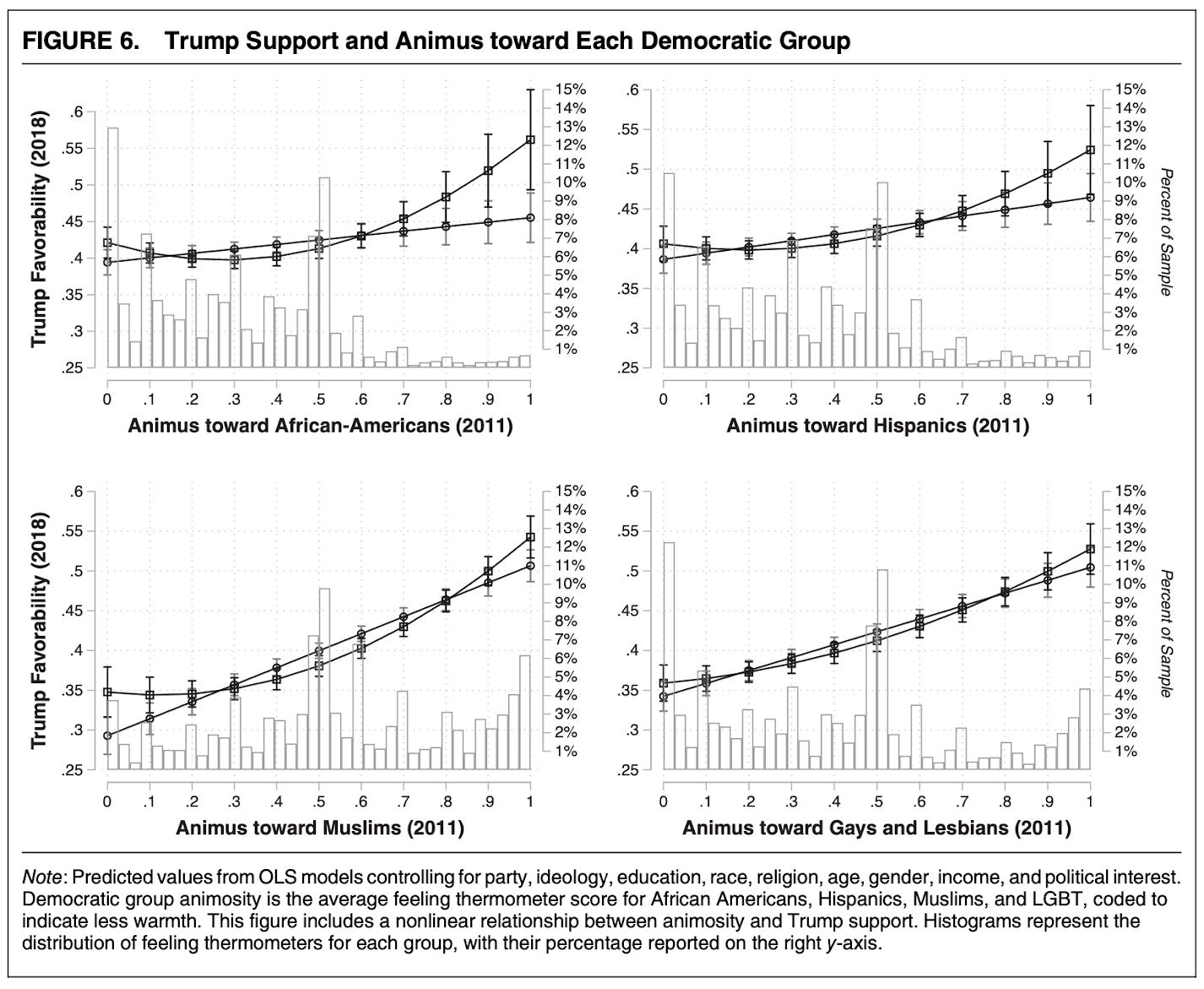

I borrow the term “MAGA faction” from a recent article from Lilliana Mason, Julie Wronski, and John V. Kane, all political scientists scattered around the US. Their article (titled “Republicans and Democrats have split over whether to support multiethnic democracy, our research shows” and published in the Washington Post this week) previews a study they conducted into the roots of support for Donald Trump. They surveyed the same respondents in 2011 and 2018 and asked Americans a variety of questions about their demographic profile, their political identities and affiliations, and their attitudes towards different groups. The following chart is the main graphic from their study, published last year in the American Political Science Review, the journal of the American Political Science Association.

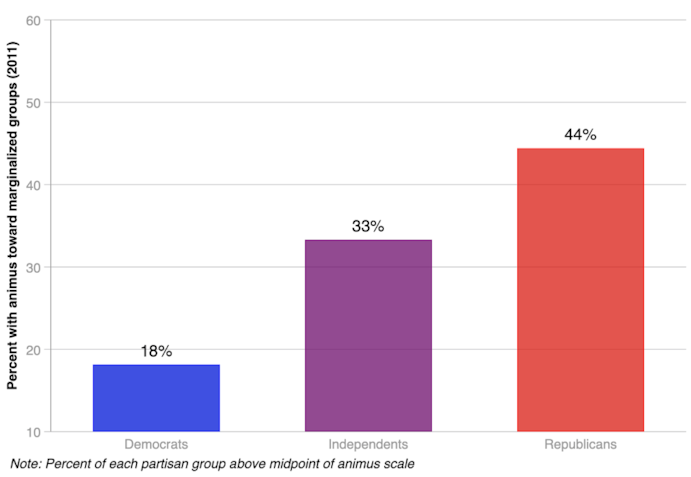

The chart shows that animus towards Black, Hispanic, Muslim, and LGBT Americans were very strong predictors of whether someone in 2011 had a favorable opinion of Trump in 2018. That’s after the scholars controlled for things like a person’s party affiliation, ideology, race, education, and religion. “Our findings reveal that Trump did not himself create this animosity,” they write, “he merely harnessed it and benefited from it politically. But democracy in an increasingly multicultural society can be threatened when a faction of citizens motivated by animosity towards marginalized groups is particularly influential within a political party. As you can see in the figure below, nearly half of Republican Party identifiers also belong to this MAGA faction.”

(And here’s the graph they are talking about in that quote.)

It is tempting to view these findings as just another psychological investigation into the 60th or 75th-percentile Trump voter. “We know Republicans score higher on racial resentment scales than Democrats,” you may object, “so what’s new here?”

This narrow view of the study is misguided. The significance of a marriage between racial animus and factionalism cannot be understated. In many ways, the history of partisan conflict in America is a history of opposition to multiethnic democracy. That is, animus toward minority groups is correlated with support for anti-democratic policies and actions. You don’t have to take my word for this!

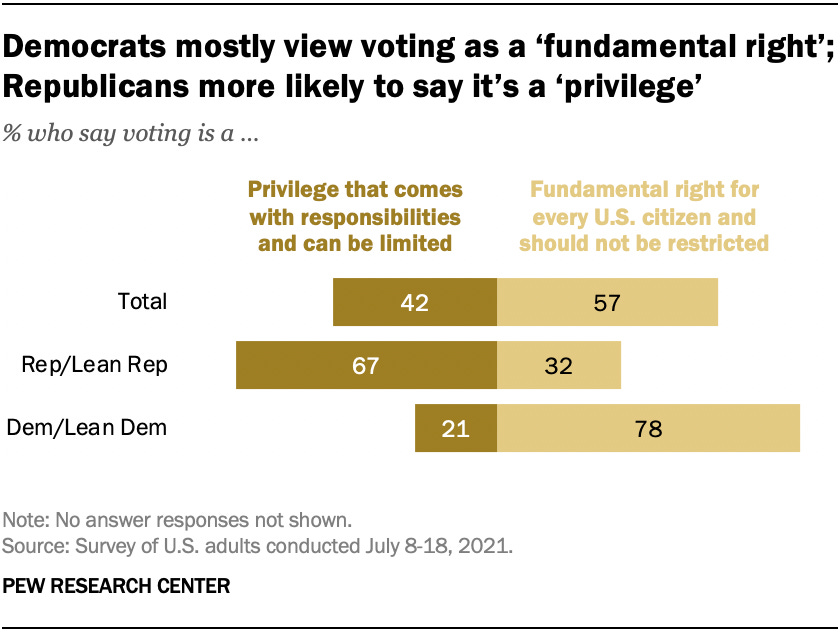

Here is a study from the Pew Research Center, for example, which finds that Republicans are much likelier than Democrats to say voting is a privilege that can be curtailed — as opposed to a fundamental right which should not be restricted:

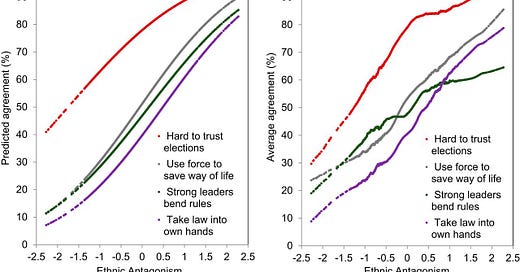

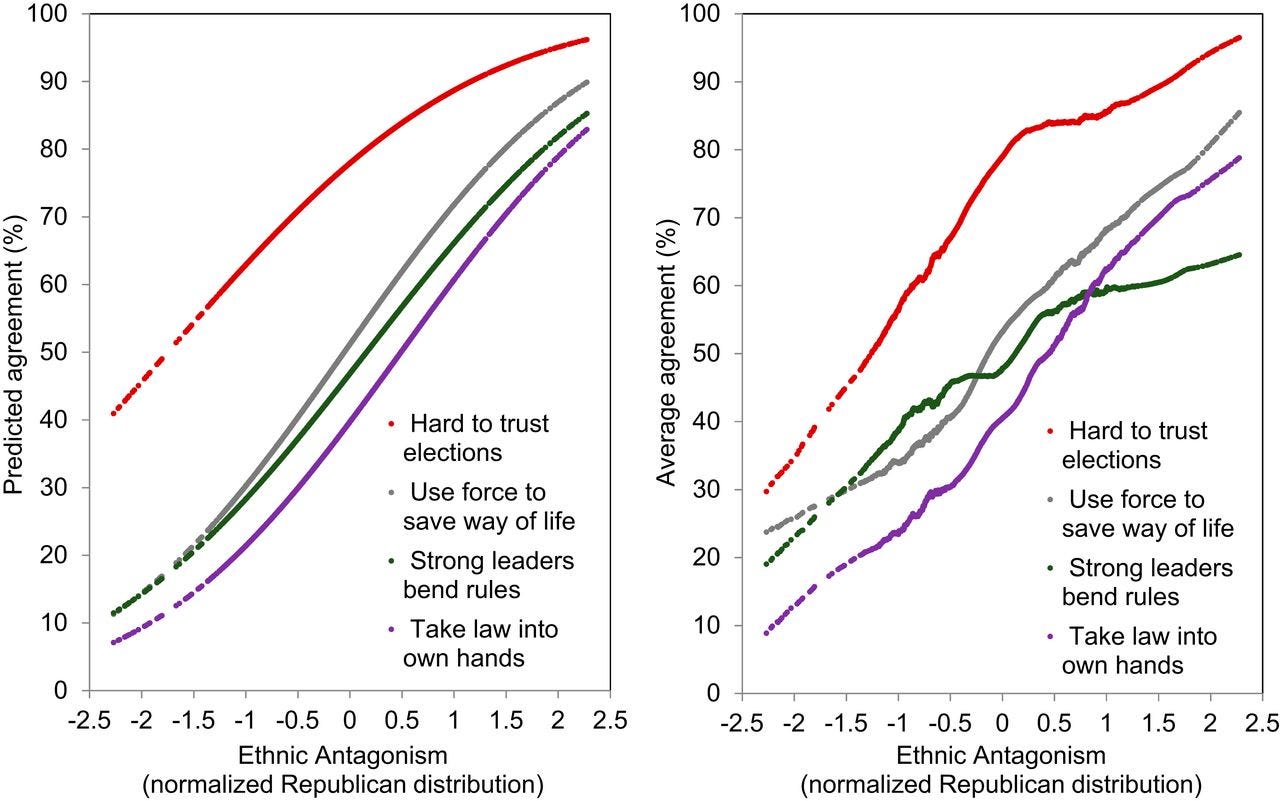

The implications here are obvious — if you violate some nebulous criteria for voting, you ought not to be a voiced member of the body politic. And there is a clear confluence of that temptation to deny rights to “unworthy” citizens with racism and white nationalism. Larry Bartels, a professor at Vanderbilt, found in a 2020 study that there was a sharp correlation between the level of someone’s “ethnic antagonism” and whether they held certain anti-democratic attitudes:

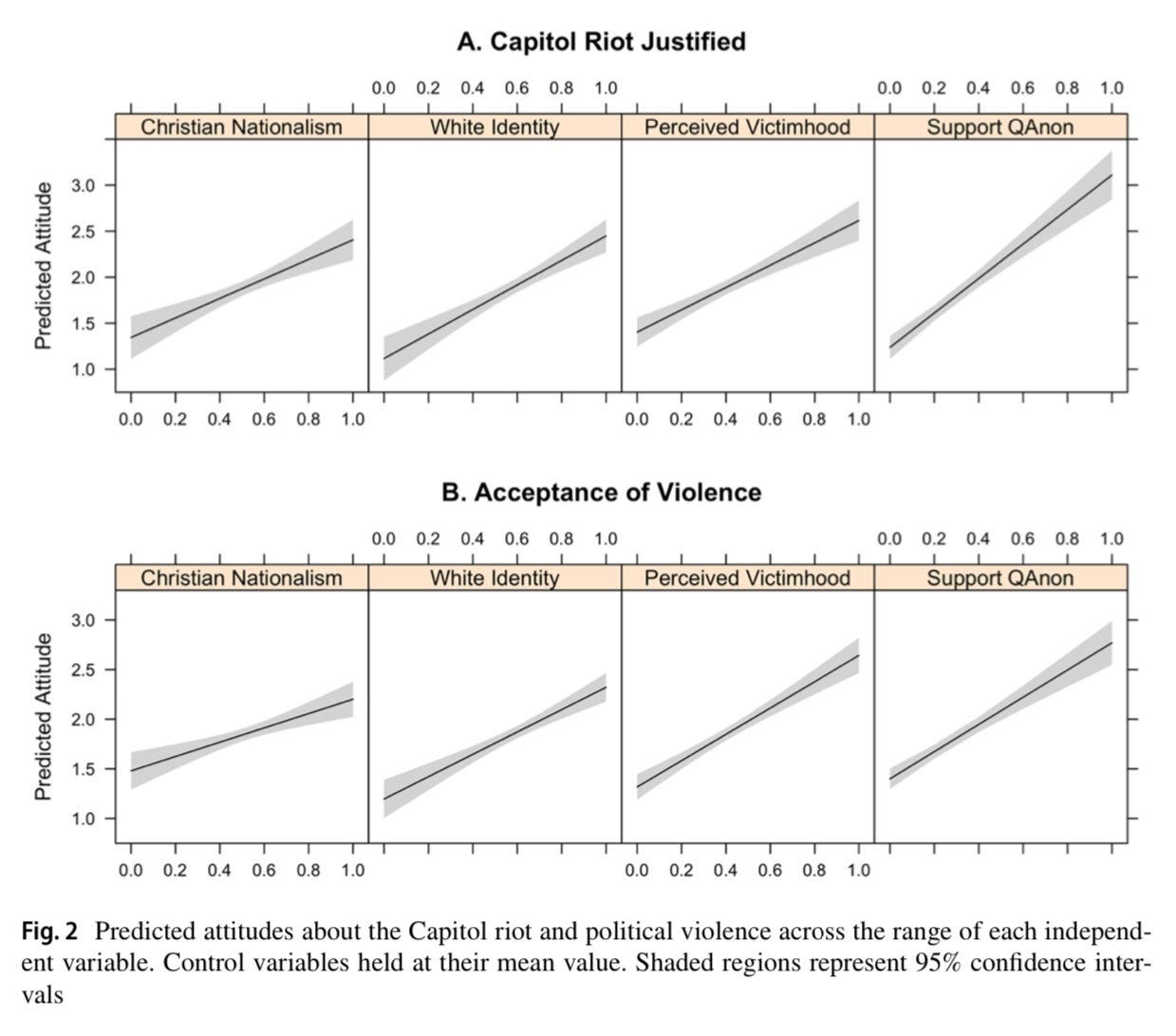

Further, a new study from Miles Armaly, David Buckley, and Adam Enders published this month in Political Behavior finds that “religious ideologies like Christian nationalism should be associated with support for violence, conditional on several individual characteristics that can be inflamed by elite cues.” Continuing, they say:

the relationship between Christian nationalism and support for political violence is sharply conditioned by white identity, perceived victimhood, and support for the QAnon movement. These results suggest that religion’s role in contemporary right-wing violence is embedded with non-religious factors that deserve further scholarly attention in making sense of support for political violence.

and the authors include this chart of their findings in their paper:

. . .

II. How to destabilize a democracy in 10 days

The above papers give us enough social science evidence, I think, to argue that the underlying problem in America is opposition to multiracial democracy — hostility to the true principle of one person equals one vote for every citizen, regardless of the various groups they (don’t) belong to.

And so we have come full circle. The other problems we face either flow from or exacerbate the consequences of this faction. After seeing these data (and, frankly, watching clips of the insurrection), we have no other choice but to acknowledge January 6th was a manifestation of opposition to Democratic victory by the people in the upper-right quadrant of the above graphs — that is, people who are both (a) hostile to non-Christians and non-whites and (b) people who hold anti-democratic attitudes. Still (to make matters more complex), it is true that their union under one party (and thus their power in Washington) has come about because of a political system that offers few incentives for moderation and concentrates this “MAGA faction” within a broader party that then must compete for their votes to win elections. I recommend you read this article for more on the institutional causes of America’s current predicament.

Yet even if we had different electoral institutions, the existence of this faction of anti-democratic voters who favor a homogenously white state would present a threat to democracy in America. The problems we face in the next decades, therefore, seem deeper-rooted and harder-solved than many people are willing to acknowledge. The solution is both that we need a Congress which incentives cooperation, moderation, and inclusion — perhaps via ranked-choice voting or true proportional representation — and parties that both fight for inclusivity and democracy for all Americans.

Only when we have both will the future of America’s representative democracy — as opposed to its flawed status quo and pure Constitutionalism — be secured. A truly inclusive state will be secured only by a groundswell in democratic patriotism among the public. Anything less than a full-throated embrace of republican and democratic (NB: note the lower-case “r” and “d”) principles by a vast majority of voters and political leaders, from both parties, will mean America is vulnerable to capture by its foes. A culture of civic-mindedness, inclusivity, support for a multiethnic state, and multiparty democracy is, accordingly, the true path forward.

Once we realize that that is what it will take, we can begin to address the true scale of the problem. It will not be solved in years or decades, but generations.

To me, then, January 6th, 20201 marked a real eye-opening turning point for America. Will democracy’s advocates put in the work to affect meaningful change, and increase the probability that its liberalizing arc of history continues apace? Or will its foes tilt the scales in their favor, succeeding in convincing enough Americans that the suspension of rights for those other people is justifiable if they can just score a few more partisan and socio-cultural victories?

I am tempted to say that only time will tell. But that is a very lazy kicker.

The truth is that, as in any democracy, it’s up to us to make sure the right vision wins.

Hi Elliott,

Great article! My conclusion a year after January 6th, is that maybe half of America doesn't want democracy. The threat of a multiethnic democracy scares too many people and people who do support democracy either don't understand the threat or can't agree on a solution. It's very unlikely that we will reform our institutions due to the fact amending the Constitution is too hard. Americans either want democracy or they don't. I don't know if we have an enough time to change people's mind before we lose our democracy.

-Elliot

Thanks much for this essay. Very important work and thought here that is so clarifying (if quite alarming). I think the focus on hostility to a multicultural polity is right on the money.

I believe that what we will experience over the coming decade or more is a devolution or shifting of political (and regulatory) power back to the states. We Dems usually think of this as reactionary, and it can and will be for those people in states monopolized by the ultra-conservative. But in fact, especially when you layer into the equation the really reactionary current (and long into the future) Federalist Society affiliate: SCOTUS, having the Dems and pro-multi-ethnic democracy people and organizations proactively working to manage this shift of power to the states through a super-charged version of what you describe as a focus on asserting and growing democratic engagement, civic-mindedness, building strong democratic practices and institutions, and so forth, may be the only way to stave-off the worst aspects of the current anti-democratic takeover of our country, including the likelihood of violence. Of course this will also need to be combined with equally strong efforts to protect, preserve, and where possible, strengthen, the federal laws and institutions that have been the focus of Dems to date.

We need so much more thought and action around how to stave off the worst of the imposition and normalization of anti-democratic policies and practices that now seems inevitable over the coming years. Your essay and the work the you cite, along with that of many others (like Corey Robin, David Shorr, for instance) is so important. I hope you will make this essay available to the public so that it can be shared as broadly as possible. Thanks.