The nightmare before Iowa 📊 February 2, 2020

What a surprise decision to cancel the final Iowa Poll tells us about polling's impacts on democracy

Welcome! I’m G. Elliott Morris, a data journalist at The Economist and blogger of polls, elections, and political science. Happy Sunday! This is my weekly email where I write about politics using data and share links to what I’ve been reading and writing. Thoughts? Drop me a line (or just respond to this email). Like what you’re reading? Tap the ❤️ below the title and share with your friends!

Dear Reader,

This week’s main read: I’ve been thinking a lot recently about which way the causal errors between public opinion, political polling, and modern democracy actually point. A decision by CNN and the Des Moines Register last night to not release the final iteration of The Iowa Poll (because of technical issues) got me thinking more about this. How exactly do polls shape our democratic outcomes?

Plus, what we can learn from some swing-state polling on Medicare for All and whether the Democrats’ political priorities? Are they actually as divided as some are saying? And I wrote a lot this week that I think is relevant enough to share here.

Thank you for reading my weekly email! Please consider sharing online and/or forwarding to a friend. The more readers, the merrier! If you’re shy, the best way you can support my newsletter is to press the heart button below the title (this makes it rank higher in Substack’s curation). If you’d like to read more of my blogging I publish subscriber-only content 1-3x a week on this platform. Click the button below to learn more!

—Elliott

Extra extra read all about it!

I surprised myself and wrote a 3,500-word piece yesterday about the future of our democracy. Give it a read and if you like it, please consider a paid subscription to my newsletter. Good writing (if you believe that’s what this is) is worth supporting—and books ain’t free!

The nightmare before Iowa

What a surprise decision to cancel the final Iowa Poll tells us about polling's impacts on democracy

Ann Selzer has attained almost mythic status in American politics for her uncanny ability to poll the Iowa caucuses. It is a tough contest for pollsters to measure for a few reasons. The kooky reallocation of votes for candidates performing worse than a given threshold makes first-choice support in a poll not translate well to final results in the caucuses. Adding to the difficulty is how to figure out who will be new to caucusing this year, and whether their political leanings are different than typical caucusgoers. Yet Selzer has done well.

That’s why #ElectionTwitter completely blew up on Friday night when Selzer & Co.’s final pre-Iowa poll for CNN and the Des Moines Registered was canceled. According to the DMR, an unusual error occurred that led to a candidate’s name being left off an interviewer’s screen at least once. The DMR’s editor wrote:

While this appears to be isolated to one surveyor, that could not be confirmed with certainty. Therefore, out of an abundance of caution, the partners made the difficult decision not to move forward with releasing the poll. The poll was the last one scheduled by the polling partners before the first-in-the-nation Iowa presidential caucuses, which are Monday.

J. Ann Selzer, whose company conducts the Iowa Poll, said, “There were concerns about what could be an isolated incident. Because of the stellar reputation of the poll, and the wish to always be thought of that way, the heart-wrenching decision was made not to release the poll. The decision was made with the highest integrity in mind.”

The Register has published the Iowa Poll for 76 years, and it is considered the gold standard in political polling. Selzer & Co., which conducts the poll, is recognized for its excellence in polling. It is imperative whenever an Iowa Poll is released that there is full confidence that the data accurately reflects Iowans’ opinions.

For what it’s worth, I think that it was definitely the right call to cancel the release.

But here’s where things get dicey. Apparently CNN had scheduled a whole hour of television coverage specifically about this singe poll. When it didn’t materialize, they had to scramble for something else. This is just one example that shows exactly how much weight political analysts were putting on the final poll from Selzer.

This raises two issues. First, it is obviously divorced from the mindset of aggregation that we should be waiting for a single poll to update our (well-informed, at this point) priors about the race in Iowa. As I’ve said repeatedly over the past week, given the large margin of error on the average of Iowa polls since the 1980s—about 10 percentage points for any candidate’s vote share, by my reckoning—and the close race there in the averages today, our best prediction for the race should probably be that we have no idea what’s going to happen, save for saying that higher-polling candidates like Bernie Sanders and Joe Biden will probably perform better than lower polling ones such as Amy Klobuchar and Andrew Yang.

But then I got to thinking about how polls—or, in this scenario, the lack of polls—influence our politics. When CNN/DMR/Selzer didn’t release this poll, what new timeline did we enter? What can we hypothesize would have happened in the counterfactual in which they had released the poll?

There are two things to mention here. First is that Iowa is almost as much about “beating expectations” than it is about actually winning the caucus. And who sets those expectations? Mostly the media. So when CNN doesn’t get their final poll and has to cancel their relates segment on Friday night, the conventional wisdom about “expectations” for each candidate doesn’t get updated. What if they had shown another good poll for Bernie, as would probably have been the case given how strong the last one was for him? Expectations for him would likely have gone up.

This brings me to the second point about how polls shape primary politics. Because primaries are events with tons of downstream effects from one state to another, polls that influence the expectations game in Iowa also influence the performance of candidates as the contest progresses. So we sit here today writing about politics in a world in which Sanders needs to get about ~25% of the vote to be considered a “winner” in Iowa. So if he wins 27% tomorrow, he’s suddenly caught fire going into New Hampshire. Then Nevada. Then and South Carolina. And on and on and on.

But what if the CNN/DMR poll had pushed expectations for Bernie’s vote share up to 30%?. Even if he wins the same 27% of the vote in this counterfactual, he’s now not doing well. Media coverage of his campaign turns sour. Some of his supporters move to different options, and supporters of other candidates (or undecided voters) are less likely to flow to him.

You can see how this can get us into a pretty sticky situation really quickly.

Now allow me to refine my point. It’s not the polls that are impacting democracy in this case, but media coverage about the polls. And so I’ll make my final recommendation: don’t treat any single poll as gospel. If you’re a journalist, don’t base your entire expectations for Iowa on one single datum that might not materialize. If you’re a network news anchor, keep in mind that your coverage of the race will impact the democratic process. (And, just to beat a dead horse, if you’re in charge of a presidential primary, don’t base debate qualifications on the polls.)

Long story short: just keep in mind that polls and our coverage of them can fundamentally change the reality of our politics.

And here are some selected links to the work I read and wrote last week:

Posts for subscribers:

January 27: This chart absolutely terrifies me. Polarization in trust in the media pushes us into irreconcilable political realities

January 31: Obama-Trump voters are still Trump voters. Yet they are not monolithic

Links and Other Stuff

Would Medicare for All doom the Democrats?

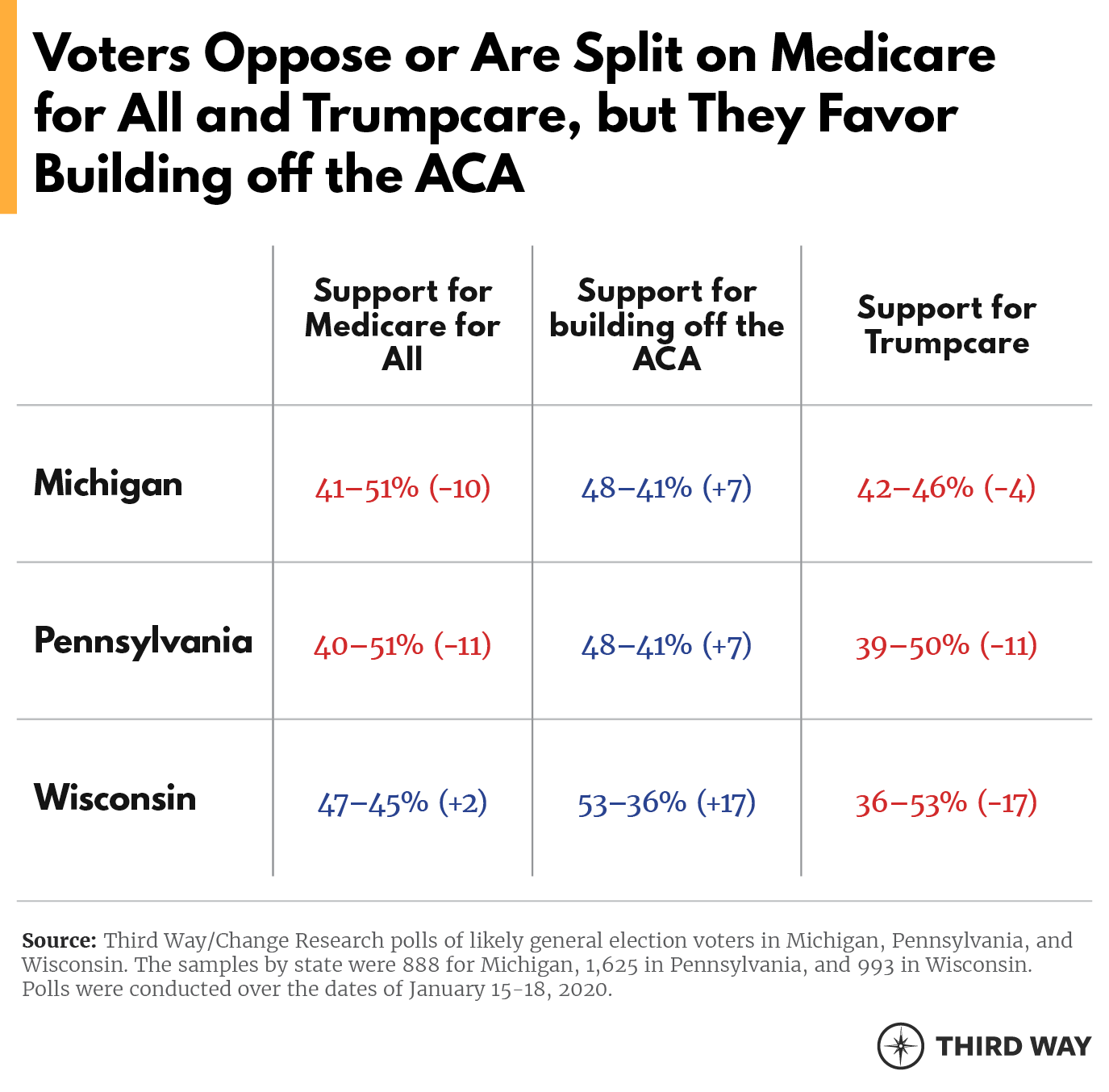

A poll released this week from Third Way, the centrist Democratic think tank, found that Medicare for All is less popular than building off the Affordable Care Act in key swing states. They find that Trumpcare is way less popular than both in Wisconsin, the assumed 2020 tipping point for the electoral college:

One reason to take this with a grain of salt is that the poll comes from a firm named Change Research, which uses a very atypical method of polling social media users online to conduct its surveys. Their samples can be pretty wacky (the look about 10 points biased against Joe Biden in the 2020 Democratic primary in South Carolina, for example) so that could be playing with these numbers too. But it’s no surprise that the center-left healthcare argument is more popular among Democrats than the more progressive on. After all, only half of Democrats call themselves liberals.

But are Democrats really divided over ideology?

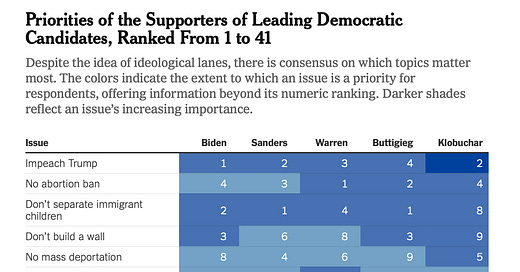

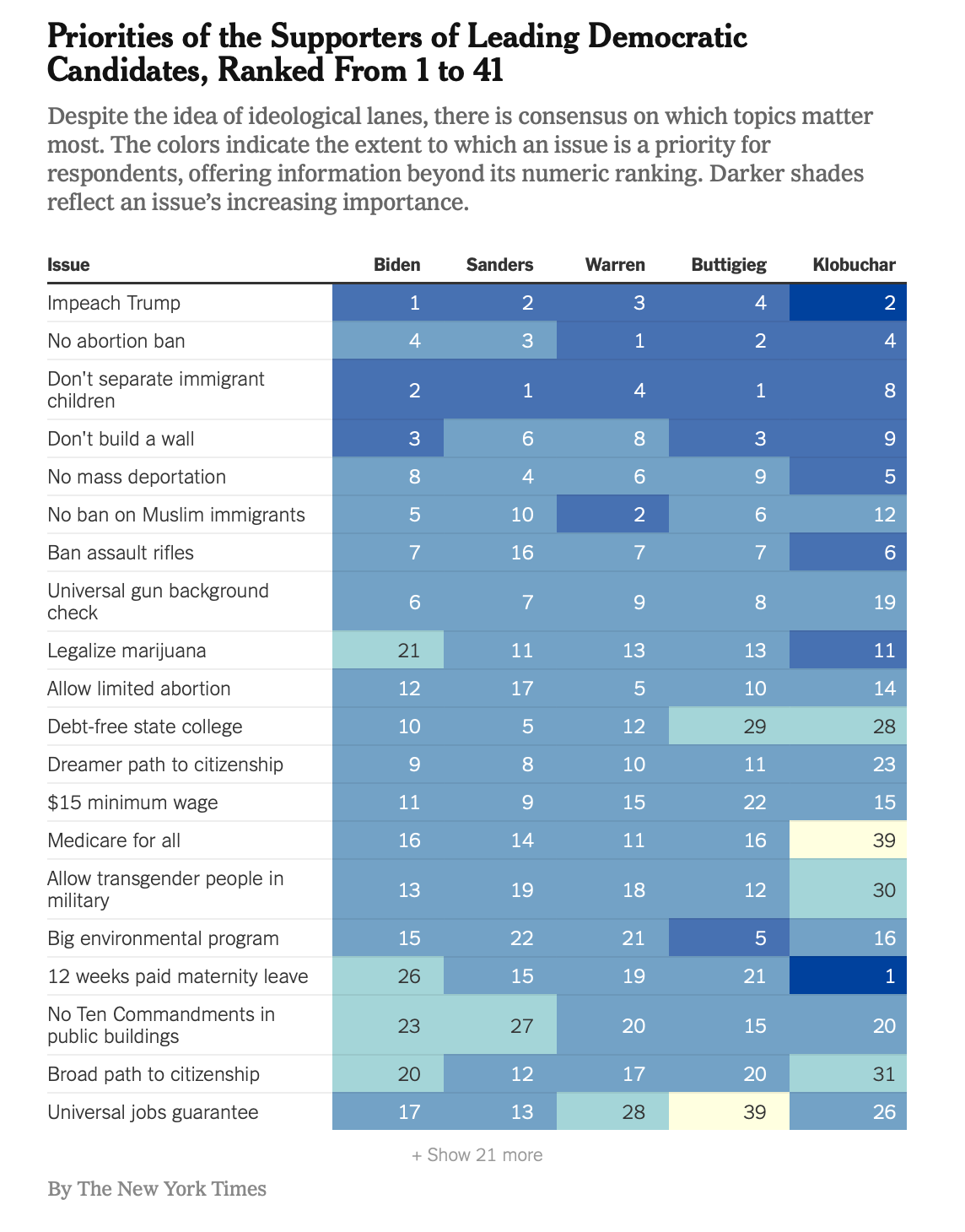

Research from UCLA political scientists Lynn Vavreck and Chris Tausanovitch shows that Democrats aren’t really as divided over policy as we think:

Despite a campaign that has been focused on issues like Medicare for All and a Green New Deal, the policies that Democrats think are most important — impeaching Trump, preserving Roe v Wade and keeping immigrant families together—they almost unanimously agree on.

So what is actually dividing the party? Vavreck and Tausanovitch write:

When most people agree on policies, vote choice may largely turn on other factors, like a perception that a candidate is more dedicated to fighting for those policies; the probability of beating an incumbent president in the general election; a wish to give a new generation the chance to run things; the hope of putting a woman in the White House.

Of course, similarities across voters on policy preferences don’t imply similarities across candidates, and some voters will care about the distinctions even if, on average, everyone’s supporters want the same things. What’s clear is that policies aren’t driving division among most of the supporters of these candidates. If there is a fight for the future of the Democratic Party, it doesn’t appear to be playing out in terms of what voters want from their government. On that, no matter whom they may vote for in the primary, Democratic voters appear to be driving on a one-lane road.

What I'm Reading and Working On

Buckle up folks because I was busy last week!

First, read my piece for The Economist on which Democratic candidate will probably fare best against Donald Trump in November.

I also wrote for the paper’s Graphic Detail section this week about what would happen in the Democratic primary if the party used ranked-choice voting.

Finally, I wrote for our US politics newsletter Checks and Balance about the sizes of polling bumps winners and losers in Iowa have tended to receive in the past.

Next week will be Iowa, Iowa, Iowa. What does the result tell us? Did polls do well or not? Etc. etc. I’ll be back next week with all those answers and more!

Thanks for reading!

Thanks for reading. I’ll be back in your inbox next Sunday. In the meantime, follow me online or reach out via email if you’d like to engage. I’d love to hear from you!

If you want more content, I publish subscribers-only posts on Substack 1-3 times each week. Sign up today for $5/month (or $50/year) by clicking on the following button. Even if you don't want the extra posts, the funds go toward supporting the time spent writing this free, weekly letter. Your support makes this all possible!