The Latino shift to Republicans is real, but it's (mostly) not about whether someone has a degree | #203 – July 24, 2022

Thoughts on "education polarization" and a new study claiming Hispanics did not move right at all from 2016 to 2020

I like to think that things happen for a set of reasons — that causes have effects and effects have causes. Lots of other people think this too. Do not jump down the stairs (or you will break your ankle). Do not bite the hand that feeds you (or you will not get fed). If I run really fast I will get tired.

But while humans are pretty good at accurately identifying causality in the real world (I know that if I break my ankle by jumping down the stairs then it is partly my fault for doing a stupid thing, and also partly gravity’s for pulling me down), it is not so easy to figure this out with data. That is why your next ice cream cone probably won’t murder you.

There are several aspects of political data analysis that muddy the waters of causality. I was reminded of this by an ongoing debate over why Donald Trump did better among Latino voters in 2020 than he did in 2016. Because we cannot ask every American why they voted, we have to guess their reasons for doing so by looking at relationships between variables we can measure with surveys. Some evidence shows that lower-education and more conservative Latinos were especially likely to vote for Trump; maybe, then, we are seeing “a political realignment in real-time,” as Axios called it in a recent article. They say that: “Democrats are becoming the party of upscale voters concerned more about issues like gun control and abortion rights. Republicans are quietly building a multiracial coalition of working-class voters, with inflation as an accelerant.”

But it is important to realize that this is not evidence of causality. A recent collection of tweets exchanged by myself and other political analysts highlights both an array of causes for this apparent Latino shift from 2016 to 2020 and even posits different theories for voter behavior altogether. There is evidence of a strong link between racial liberalism and voting for Trump; low socioeconomic status and voting for Trump; not having a college education and voting for Trump; living in areas with lower shares of degree-holders and less income and voting for Trump; and on and on. And how do you sort all that out? And what variables come before others?

It is worth a brief detour to talk about this. It is common today to talk, as Axios does, about Donald Trump’s gains with Latinos as a product of increasing polarization by (1) educational attainment and (2) income. Democrats are the party of upscale educated white progressives, this trope goes, and Republicans are assembling a coalition of Whites, Latino, Black, and Asian voters who do not share their interests.

This may be true to an extent, but it advances a few myths about the electorate. For one, Democrats will win the overwhelming majority of Black, Latino and Asian voters. In fact, even if you break down demographic groups by their race and education, the only group Republicans won in 2020 was non-college-educated whites; both college- and non-college-educated voters of color went for Democrats in 2020.

So maybe politics is less divided by education and socioeconomic status that pundits popularly prescribe. In fact, our behavior is divided more by our views on race, culture, and identity. For example, if you divide groups of college- and non-college-educated whites into two additional groups by whether they score higher on the so-called “racial resentment” scale, then the observed polarization by education completely disappears. The gap is captured entirely by whether someone has extremely conservative views on race and fairness.

This shift is now happening among whites and non-whites. Eg, polarization on racial liberalism now increasingly includes minorities who don’t have “progressive” views — on this and associated beliefs (hostile sexism, anti-LGBT, anti-Muslim, etc).

So, why the focus on education status? Knowing a white person has a college degree tells me that they are slightly more likely to be a Democrat. Knowing they score high for racial liberalism guarantees that they vote Democratic. This is a stronger relationship even than a person’s income, socioeconomic status, or occupation.

I suspect people have focused on education because it is neater. It is easier to say that Republicans are becoming a “multiracial coalition of working-class people” than it is to say that Republicans have gained ground among people with conservative attitudes, especially on race. And even though (1) college-educated Hispanics also got marginally more Republicans between 2016 and 2020 and (2) the shift among conservatives is much higher than among non-degree-holders, these parts of the shift are ignored in favor of the prevailing narrative about voting behavior being driven by class and “education.”

Another explanation is that the people who have been most outspoken on what Democrats should be doing to beat Republicans have competing interests than what the data prescribe. It is easy to say that Democrats should talk more about working-class issues and less about diversity or whatever. It is much harder to say that Democrats need to move to the right on culture and identity and/or get people to stop voting based on their racial resentment score. And yet, figuring out how to woo both whites and non-whites with conservative views on identity is much more useful than figuring out “how do you woo voters without college degrees?”

The prescription for how Democrats do that is also of minimal utility. Ruy Teixeira, the self-described social Democrat who recently left the Center for American Progress for the center-right think tank AEI told Ronald Brownstein for a recent Atlantic article that a more appealing Democratic party would: “Talk less about race, period.”

“They would talk less about gender. They would not go down the road of wading into all these very arcane and difficult, contentious trans issues. They would not use language that sounds like it comes out of, in James Carville’s immortal words, the faculty lounge.”

Yet he makes no mention of the fact that Democrats are not the ones raising these issues, Republicans (and Fox News) are. The actual issue here is how Democrats make politics about economics if Republicans want to make it about culture? Or, how do Democrats find messages on the culture war that appeal to 55-60% majority the party needs to win the Senate? It is hard to find an answer. And that’s why you get messaging about the “working class” and “non-college” voters despite the fact that polarization on those axes is much lower than polarization we observe on attitudinal axes.

I think some smart left-of-center strategists could come up with some really compelling answers to these questions. But those answers will not come in tracing the magnitude of “educational polarization” across racial groups.

Zooming back out now: In the social sciences, we call problems like predicting changes in voting behavior overdetermined; that is, they have many potential causes and it is not easy to identify the precise statistical value of their causal arrow. But there is another problem besides the fact that human behavior is stochastic. And that is that we often cannot directly observe those changes anyway. Our inferences are based on samples of the population telling us how they voted. And, therefore, those inferences are based on the types of people we reach.

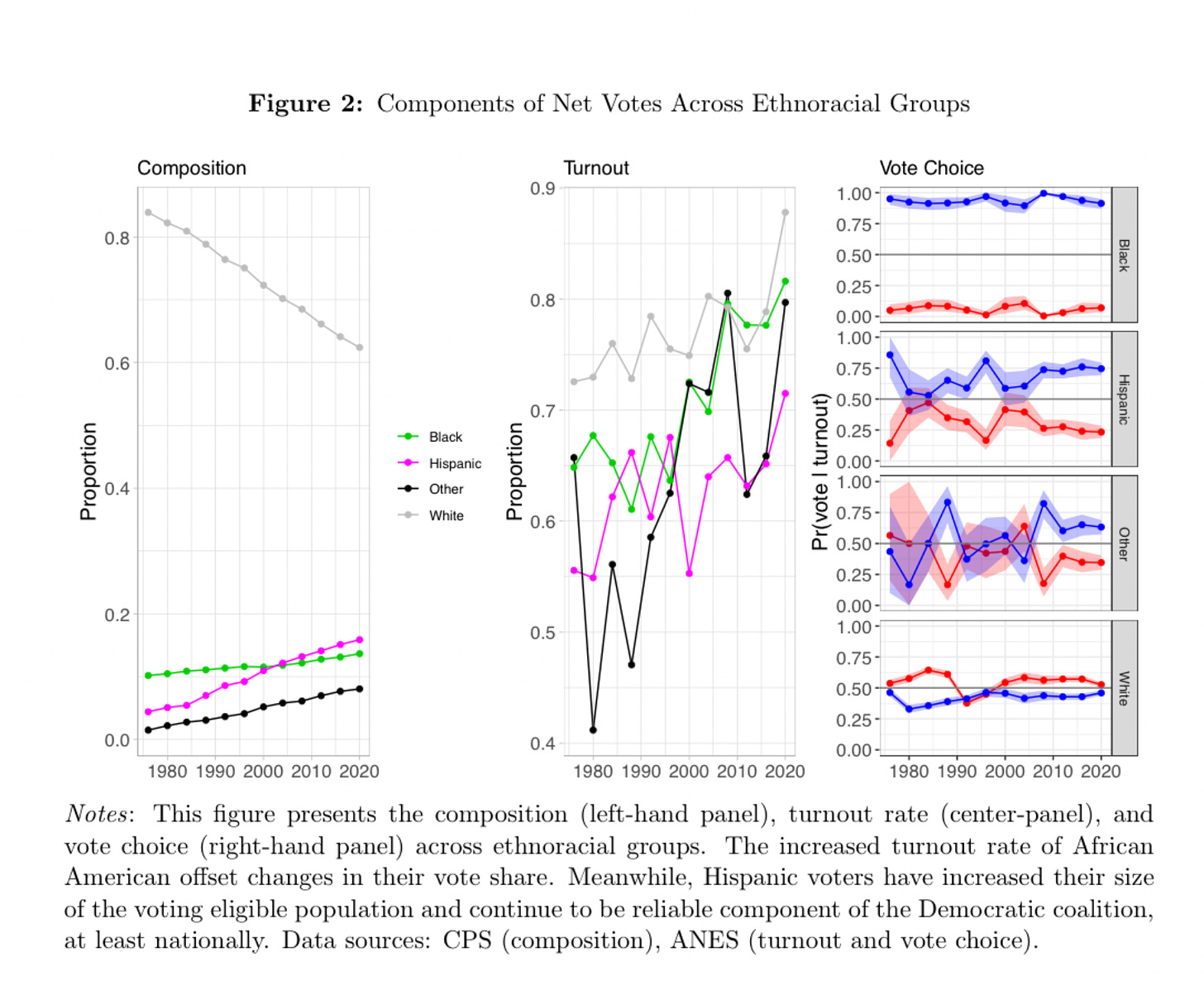

A new paper by political scientists Justin Grimmer, William Marble, and Cole Tanigawa-Lau forgets this lesson. While the paper is quite ingenious in developing a new methodology to measure how much of the changes in voting behavior among subgroups of the electorate are due to (a) changes in the group’s population size or (b) changes in turnout or (b) changes in the probability of voting for a certain party, it relies on a biased dataset of election results to proclaim that “there is little evidence that Black and Hispanic voters shifted to Republicans in the 2020 election.”

The paper really is quite cool. Instead of focusing on the percentage of a subgroup that votes for Democrats — exclaiming that Biden won less ground among non-college-educated non-whites than Clinton did — the authors propose multiplying composition, turnout, and vote choice together to get a measure of net votes for Democrats v Republicans. They use the Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey and the American National Election Study to show that Joe Biden won more votes from Black and Hispanic Americans than Clinton did, despite his vote share among the groups declining modestly. (They replicate their analysis with a variety of other data sources.)

This leads them to find that:

Recent punditry has noted some decline in the vote share forDemocrats among Black and Hispanic voters who turn out to vote. But changes in com-position and turnout rates more than compensate for these changes in vote share.

This is true, but not the same as their claim in the abstract that the group hasn’t shifted right. The probability that a Hispanic voter cast a ballot for a Republican increased from 2016 to 2020, even in their analysis.

The bigger issue here is that the Latino voters who were interviewed for the ANES and Cooperative Election Study are not representative of the actual population of Hispanics. They estimate Democratic vote shares among the group that is much higher than externally-validated estimates, such as those by Catalist. And that means that studies like these will underestimate rates of switching.

So, back to square one. I like to think that things happen for a reason—or often, a set of reasons.

In the conversation about Latino voters today there is a very striking obfuscation of more dominant patterns of voter behavior in favor of oversimplified narratives about education polarization that, on the right, offer more damning indictments of the Democratic party and, on the left, offer cleaner and more palatable solutions for strategists to advertise. People want a reason and not the reasons Hispanics are becoming less loyal to the Democratic Party.

There is another problem, too, which is that the focus on Latinos has led to an overemphasis on their changing voter behavior (the GOP is becoming “multiracial” despite the fact that 75% of non-whites voted for Democrats in 2020!) and thus a demand for counterintuitive findings, such as the claims that they did not move right at all — which is even more wrong.

And this is all made even more complicated by the fact that we cannot accurately ascertain the causality of any of these factors.

The product of these trends is an unnecessarily muddied story of voter behavior that offers no substantial solutions to any strategist looking at attitudinal and ideological correlates of voting more broadly. I think if we looked at this problem with a more comprehensive analysis of voter behavior we be much better off.

Talk to you next week,

Elliott

Posts for subscribers

If you enjoyed this post please share it — and consider a paid subscription to read additional posts on politics, public opinion, polling and election statistics, and democracy.

Monthly mailbag/Q&A!

The next blog Q&A will go out on the first Tuesday of September, or if someone asks a real banger of a question — whichever comes first. Go to this form to send in a question or comment. You can read past editions here.

Feedback

That’s it for this week. Thanks very much for reading. If you have any feedback, you can reach me at this address (or just respond directly to this email if you’re reading in your inbox). And if you’ve read this far please consider a paid subscription to support the blog.

Almost all these discussions of "working class" start from the premise that the "working class" is White. In the West and Southwest, the "working class" is Brown, Black, and newish immigrant. That's the preponderance of who is doing the work society treats as low value in many places; for all I know, that may be true in most Democratic cities. These discussions seem to me to go on mired in fictitious assumptions. Democrats need to speak to the extant working class, not to an Ohio steelworker who fears the emerging working class. Folks certainly have issues: health care, housing, ... you name it. But also feeling dissed for their non-whiteness/not American enoughness too. They may not look the way they exist in some speakers' brains.

If you go look at the Hispanic Republicans web pages, you'll see they're being played on their elders' social conservatism - crime, status of women, abortion. The planet doesn't have time for their younger people to vote us out of trouble.

A woman who has just returned from Israel/Palestine on a tour run by a progressive family foundation told me that in Israel, people talk about what they derisively call The American Solution. This solution = all parties get together and talk and a resolution will emerge. People in both countries laugh at this. The fact is that Palestinians and Israelis have different foundational narratives, which are fundamentally in conflict. The Palestinians were invaded by both British military forces and European jews, and had their lands stolen from them by force and by legal chicanery. The Holocaust survivors -Israelis were promised this same land as a homeland, by the United Nations, and they fought both the British and the Palestinians for it.

It is not a level playing field, and no peaceful resolution is probable. The same is true in the USA today. The GOP have a fundamental narrative which is in direct conflict with my values. They are heavily armed and violent and intend to prevail, law notwithstanding, by force of arms and legal chicanery. European friends say that we are heading for a civil war. We are already in it.