The doom loop and the anti-democratic whirlpool

A conversation with Lee Drutman about the authoritarian trajectory of American democracy — and the ways out

What do you do when your governing institutions start incentivizing anti-democratic behavior?

America faces some version of this question at the local, state, and national level — the Republican Party is currently waging a full-scale assault on our democracy. The party’s leaders have grown dramatically more willing in recent years to take illiberal actions in order to win power. The bending of institutions, norms, and information have made violations of the fundamental tenants of democratic theory more tolerable — the Overton window for authoritarianism has shifted far to the right.

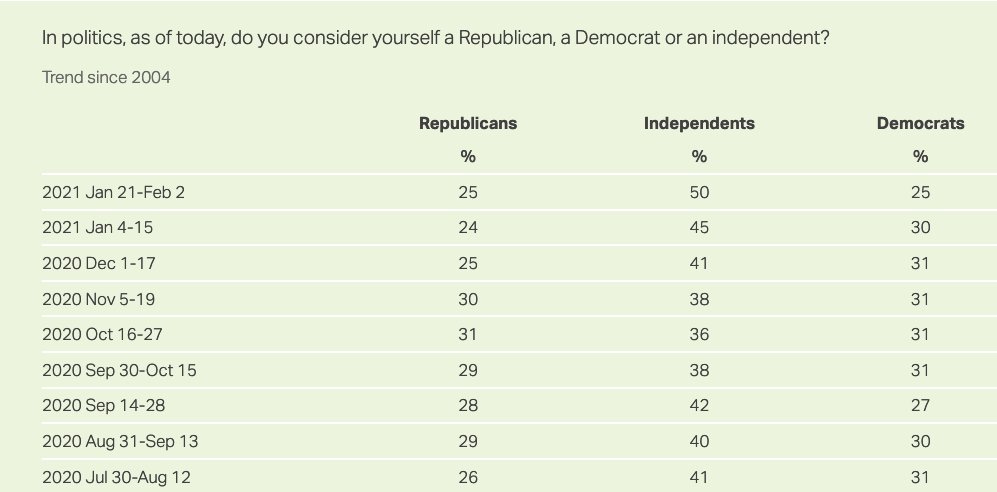

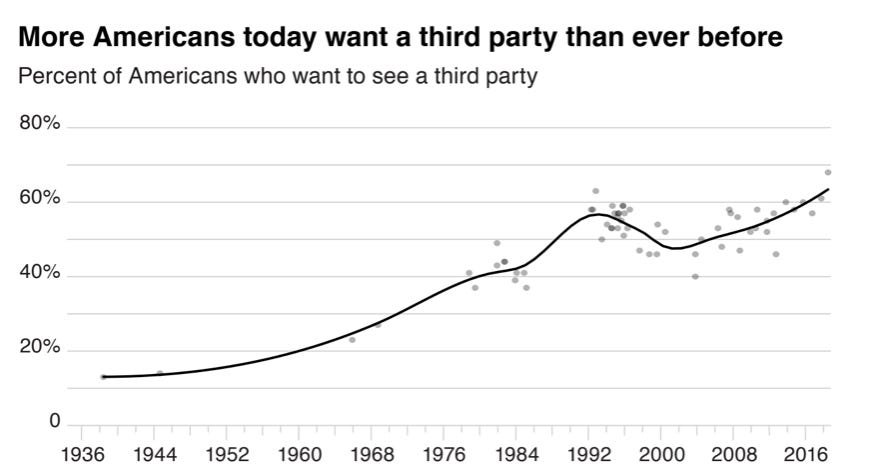

In the backdrop of all of this, Americans are increasingly ditching their party labels. Research shows they are put off by the anger and hostility of partisanship, and rightly so. New Gallup polling this week shows that half of Americans identify themselves as Independents, rather than Republicans or Democrats — a marked increase over the last few decades. Support for a third party has never been higher, according to this series.

But the vast majority of “Independents” are just partisans in disguise, Democrats and Republicans moonlighting as third-party voters during survey interviews because they don’t want to associate with the labels. But these shy partisans, what survey researchers sometimes call “Leaners” because they will adopt a partisan label if pressed, are as numerous and psychologically partisan as ever. Samara Klar and Yanna Krupnikov, two political scientists, write that leaners “lack the normatively positive aspects of partisans (for example, being politically participatory) while embracing the negative aspects of partisans (a stubborn dislike of compromise)."

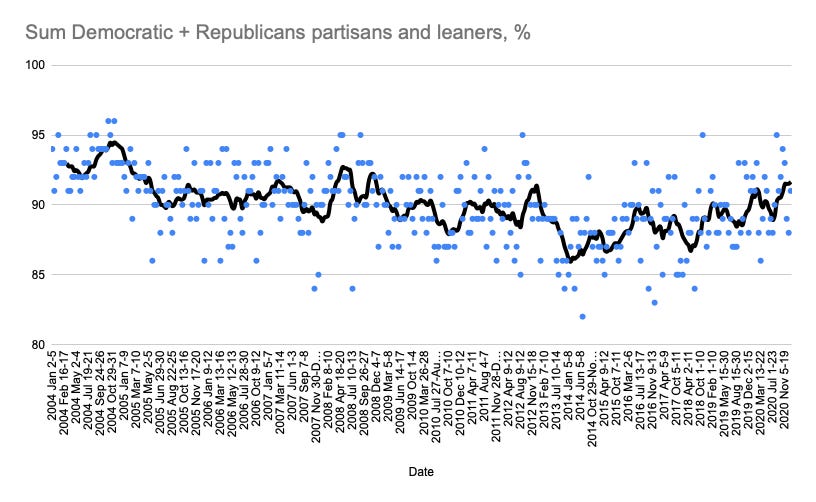

Despite the promise of the above trend in apparent Independents, my analysis of the Gallup data shows that there has been a significant increase in leaned partisanship — Democrats and Republicans plus Independents who lean either way — over the last decade:

If you’re anything like me, the above plot will give you a slight sense of shock. After the vitriolic, violent partisanship of the last few years, more people are calling themselves Democrats and Republicans? If you were hoping for partisanship to abate and for America to quickly realize a better electoral system, this might leave you a little bit disappointed.

However, it’s not fair to dismiss out of hand the possibility that a third party might lead America into a future without a two-party system. This will take a big change, but it can be done.

This is part of a broader conversation I had with Lee Drutman, a senior fellow at the New America Foundation and author of “Breaking the Two-Party Doom Loop: The Case for Multiparty Democracy in America,” about the problems of our Democratic institutions — and a few potential ways out. An interview with Lee follows below the fold.

Editor’s Note: If you found this post informative, do me a huge favor and click the like button at the top of the page and the share button below. As a reminder: I’m fine with you forwarding these emails to a friend or family member, as long as you ask them to subscribe too!

GEM: First, do we know anything concrete about what’s driving the demand for a third party? It seems like Republicans want the party to move right. Are these Trump’s Patriot Party voters? What about the left?

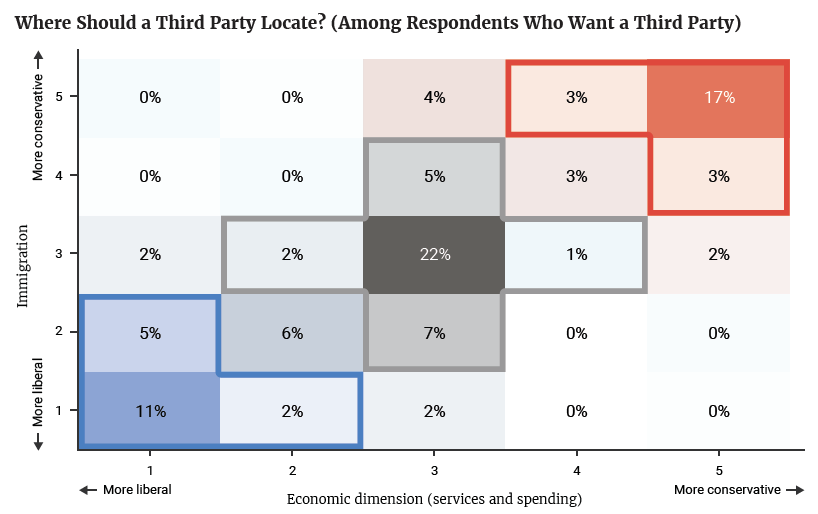

LD: Well, we know a few things. First, in a 2018 Voter Study Group report, we looked at voters who wanted a third party, and here’s what we found:

“Among the 68 percent of voters who support a third party:

Almost one in five (18 percent) want a party that is more liberal than the Democrats on one or both dimensions, and 11 percent want a party that is more liberal than the Democrats on both dimensions.

Roughly one in three (37 percent) want a party that is more centrist than either of the two parties on one or both dimensions (while not also being more liberal/conservative than a major party on another dimension), and 22 percent want a party that is more centrist on both dimensions.

Slightly more than one in five (23 percent) want a party that is more conservative than Republicans on one or both dimensions, and 17 percent want a party that is more conservative than Republicans on both dimensions.”

Second, we know that support for a third party has been relatively high for a while now, going back to the early 1990s. See this chart from my book:

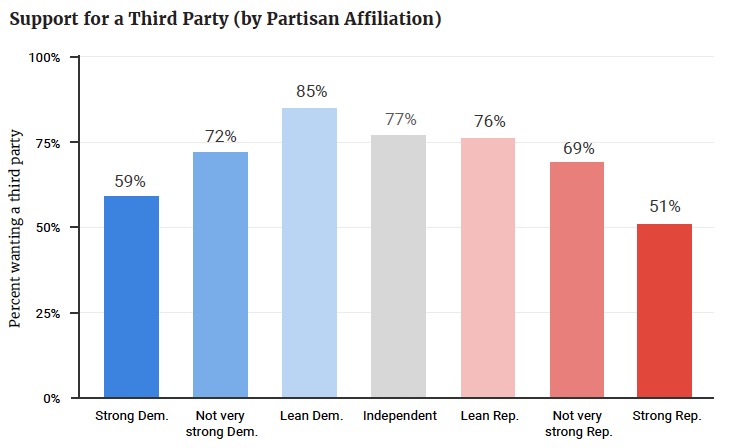

This support also seems to rise alongside the share of people registering as independents, though in the Voter Study Group Spoiler Alert, even majorities of both Strong Democrats and Strong Republicans thought there should be a strong part:

My read is that it reflects dissatisfaction with politics, partisanship, and political institutions writ large, and that for many voters, this dissatisfaction is more diffuse and general — there’s a sense that something has gone wrong, and that we need some kind of change. This helps explain why candidates are constantly running as political outsiders to the extent they can.

Any third party that does form would be doomed, according to the thesis from your book, right? Or is there something special about our politics right now that could make it more successful?

American politics has long been hostile to third parties for a number of reasons, but most significantly, in our system of single-winner plurality elections (aka “first past the post”) votes for third parties are considered wasted votes, and so all energy and ambition and money flows to the two major parties. This creates a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy, that third parties are doomed. At various moments, third parties have gained modest traction in the US, but only when either 1) there was a major split in one of the major parties (I’m thinking about the Republican Party in the 1850s, which was built atop a Whig split over slavery) or 2) more commonly, the two major parties were indistinguishable on a major issue that lots of voters cared about (here I’m thinking the Populist Party in the 1880s, Robert LaFollete’s Progessive Party in 1924, George Wallace’s American Independent Party in 1968, and Ross Perot’s Reform Party in 1992). But today, there’s such a gap between the two major parties that few voters are indiffirent enough to support a third party.

Talk me through the implications of a major third party. I’m not sure what it would look like right now. Maybe a party for the voters ideologically most similar to Joe Biden and Mitt Romney? A Centrist party. What effect would that have on politics? What can we learn from this thought exercise?

I’m not sure either. The most likely third party would be a center-right party of principled Republicans (think Adam Kinzinger), but that would at best be a 15% party, unlikely to win more than a few House Seats and maybe one or two Senate elections. It’s possible such a party could hold the balance of power in an otherwise even House or Senate, but that’s a very long shot. The problem is that there are simply not enough voters in the political center to form a party that would come anywhere close to numerically exceeding either the current Republican or Democratic Party. What we need would be five or six parties, but without proportional representation, that would be absolute chaos.

Ok. Now, what does your book say about the way out. Could a third party be on the path toward multiparty democracy? Or does the reform have to come from inside the existing two-party system?

So, there are three ways to think about this.

One, which is more globally informed, says that a third party is the precursor to the kinds of proportional electoral reform necessary to allow for more parties to compete fairly. That’s because it takes a few “spoiled” elections to highlight the inherent unfairness first-past-the-post elections, and the threat of a rising third party to lead one or both of the two major parties to realize that a more proportional system could keep them from total irrelevance. For exmaple, one of several reasons that New Zealand moved to proportional represention in the 1990s was that a centrist third party had contributed to the more conservative party winning control of parliament repeatedly despite losing the popular vote. But zooming out here, the motivating factor is really uncertainty and unfairness, and the desire for some stability and more fairness.

Second, which is more US-centric, is that the US is just weird, and that our major parties are inherently weak and factional because we have just two of them, and they both have to be big tents, so that the impetus for reform could come from factions within the two major parties who both see themselves as marginalized. The challenge here is if those are the marginalized factions, they likely lack both the votes and power.

Third, which is more historically informed, is that the US periodically goes through cycles of democracy reform, every sixty or so years, and that we’re due for another of these cycles (the last one was in the 1960s), and that the motive for reform will really come from grassroots activists and social movements, and that political leaders will champion reform when it is widely popular.

I think all three factors are potentially at play right now. The fact that both Democrats and Republicans are fighting over the basic rules of democracy indicates a high level of instability, and proportional representation can be a stabilizing force here, by breaking the zero-sum partisan logic driving these fights. Proportional representation can potentially stabilize politics, which might make it attractive to many who are just exhausted by the hyper-partisanship that is destroying the foundation of electoral fairness on which democracy depends. The parties are quite divided internally, more than may appear so on the surface. And I think we are seeing the early signs of a grassroots movement for democracy reform. Major democracy reform always seems improbable. But it seems more likely right now than any time in my lifetime.

Lee is rather hopeful about the path to reform. Of course, someone in his position — an ambassador for a new America — is necessarily reasonably optimistic because of their job. But these are real reasons to hopeful. I am not crazy about the idea that America must have “a few spoiled elections” before people catch on tot he danger, but, if that’s what it takes so be it.

One additional possibility that Drutman doesn’t list is that the increasing demand for both (i) a third party and (ii) reform will cause enough good-faith Republicans to get on board with legislation like HR1, which curbs partisan gerrymandering and enacts an array of policies that make voting easier, to pass it. A bill like HR1 would decrease the chance that Republicans could simply pass state-level laws restricting access to the polls — laws that often disenfranchise Democratic voters more than their own.

But the candidates for this are few and far between. Arizona Republicans right now are making their case to the Supreme Court that the partisan bias of election laws is actually a ground for deciding litigation in their favor. Here’s a clipping from a recent NBC News article:

An attorney for Arizona's Republican Party offered a blunt reason for his presence defending the state's voting restrictions before the Supreme Court on Tuesday: The measures disadvantage Democrats.

The Supreme Court is hearing arguments over Arizona voting restrictions in a pair of consolidated cases challenging a state law banning ballot collection and a policy that tosses ballots cast in the wrong precinct. Democrats have sued, saying the rules discriminate against minorities and violate Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act.

The case could have big implications outside of Arizona if the justices create a test for how to evaluate such voting rights cases under the voting rights legislation.

“What’s the interest of the Arizona RNC in keeping, say, the out-of-precinct ballot disqualification rules on the books?" Justice Amy Coney Barrett asked, referencing legal standing.

“Because it puts us at a competitive disadvantage relative to Democrats,” said Michael Carvin, the lawyer defending the state's restrictions. “Politics is a zero-sum game. And every extra vote they get through unlawful interpretation of Section 2 hurts us, it’s the difference between winning an election 50-49 and losing an election 51 to 50.”

This passage exemplifies what Drutman is saying about the two-party system incentivising anti-democratic behavior. The current iteration of the Republican Party sees election laws as an avenue for partisan advantage, and will explore any possibility — and trample every norms — possible to gain an edge over the competition.

This is a result of the “doom loop.” And, sadly, it is only really the beginning.

But the doom loop is not really a loop. It is a whirlpool; A nascent democracy with plurality electoral rules starts at the surface level, making one or two revolutions around the vortex as they violate a few norms or pleasantries in order to gain an edge over their opponent. But soon, they sink an inch — one of the parties has just restricted voting for a racial or political minority in order to win an election. The country gerrymanders its districts and sinks again. At each revolution, with the stakes of partisan competition ever-increasing, the party system is sucked further into an anti-democratic whirlpool — until, at one point, the institutions break, and reform is born.

Americans, pulled ever deeper into the whirlpool, face two questions:

First, what do you do when your governing institutions start incentivising anti-democratic behavior?

And, second, how willing are you to drown for your party?

It will take a few electoral hiccups for party leaders to reform the system. But if the people don’t want to drown, don’t want to see the economic and social consequences of political gridlock and partisan antipathy, they have the power to change the system themselves. Hopefully, they will do it sooner rather than later.

Third party candidates can be spoilers. That can be useful. . .