Welcome! I’m G. Elliott Morris, data journalist at The Economistand blogger of polls, elections, and political science. Happy Sunday! Here’s my weekly newsletter with links to what I’ve been reading and writing that puts the news in context with public opinion polls, political science, other data (some “big,” some small) and looks briefly at the week ahead. Let’s jump right in! Feedback? Drop me a line or just respond to this email.

This newsletter is made possible by supporters on Patreon. A special thanks to those who pledge the top two tiers is written in the endnotes. If you enjoy my personal newsletter and want it to continue, consider a monthly subscription for early access and regular blogging for just $2.

This Week's Big Question

What could happen on Tuesday? Why? Midterm expectations, justification, and a guide for election night.

In crafting my expectations for Tuesday’s midterm elections — contests so important that they could decide “the political fate of America” (🤔🤔) — I find myself lost in a sea of narratives. Will this be the (next) Year of the Women™️? Are suburbanites revolting against Trump? Are Obama-Trump voters coming home? Is this year just a typical reversion to the mean? Ultimately, we cannot know until Tuesday evening, but that hasn’t stopped us from trying to figure it out so far, and it won’t stop me now. I want to explore the different facets of each of these narratives.

Flowing naturally from that, here’s a long (clocking in at 3,000 words) piece on midterms expectations, justifications, and a preliminary guide to diagnosing what happened on election night — what I’m calling a “pre-postmortem.” Let’s take a stab at figuring out what happened before it does, with a prospective look at why that outcome occurred by dissecting different demographic scenarios.

Closing arguments

If I were to frame the choices that voters have on Tuesday — and have had over the past 3 weeks of early voting, in which 34 million Americans have already cast ballots —as two options, it’s between Trump and Democrats. I don’t have to remind you that midterm elections are referenda on the party in power. Indeed, according to my analysis of the individual respondent data from NYT Upshot/Siena College’s “live” polling, the biggest predictor of vote choice in the midterms is whether or not someone approves of Donald Trump. Though The Economist’s polling with YouGov is a smaller sample size (we have 40,000 respondents in the NYT polling, vs 1,500 weekly YouGov panelists), it also confirms this trend; in last week’s polling, about 90% Trump approvers were likely to vote for House Republicans in this week’s elections.

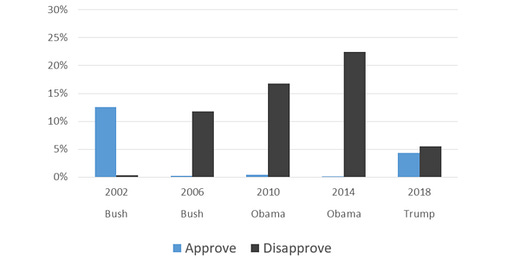

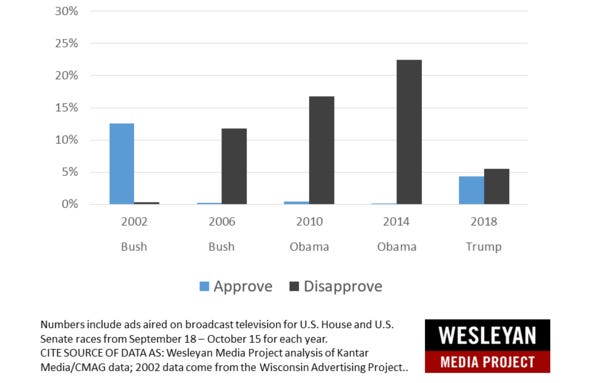

Still, the election is not only Trump vs. the alternative (whatever it may be). Instead, candidates are campaigning on promises of policy implementation (and repeal). The Wesleyan Media Project, as I wrote last week, found that 47% of Senate and 61% of House, Democratic TV advertisements this cycle mentioned health care. Overall, the lowest share of advertisements since at least 2002 conveyed messages that praised or chastised the sitting president. Although the fundamental indicators and public polling tell us that Trump support gets us 80-90% of the way to predicting a person’s vote intention, the remaining 10-20% is (importantly!) explained by other issues.

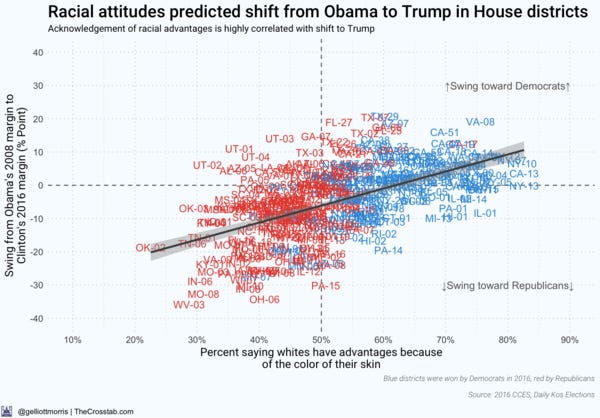

Of course, the focus of the campaign has changed over time. Whereas immigration was more of a policy issue in early 2018, the final weeks of the campaign have seen a sharp rise in the GOP’s use of the issue to fear-monger efficiently enough to send their voters to the polls. Ever since the Republican party — and especially Donald Trump, though his command of the party’s race-baiting wing of socially conservative voters came long after the GOP introduced it — made racial animus a focal point of the 2016 campaign, attitudes of resentment and white identity among the public have become especially salient to a large swath of voters. Political scientists reckon that (white) identity politics is one of the predominant forces in American politics today.

Commanding such power, Trump might well be able to shape the outcome with this strategy. However, public opinion polling has shown no indication that this is the case. It may be that the parties have already (re-)realigned on this issue. In other words, attitudes of racial animus may have predicted a swing from Obama to Trump, but will it also predict a swing back (among the relevant voters)? Or a continued shift toward Republicans (again, among the relevant voters).

Trump’s gamble just might be worth it, but since we’re seeing bigger shifts (back) toward Democrats in Obama-Trump congressional districts as compared to Romney-Clinton or consistent partisan districts, it’s unclear that it will. It’s probably a fool’s errand to try to figure that out now, with just under 34 hours to go until election results start rolling in.

Democrats are also hoping that they can market the president’s morals as repulsive enough to spur both turnout and persuasion among suburban, college-educated whites — and especially women. They looked poised to do so, at least to some extent.

Mainly for these reasons, but also others — congressman Steve King of Iowa’s 4th congressional district is being chastised for racist comments, and Chris Collins and Duncan Hunter could be headed for defeat because of corruption scandals — Democrats look poised to gain enough House seats to form a majority. Their path(s) to 218 seats run mainly through these issues and demographic patterns outlined above. But just how likely is that? And what about the Senate? Governorships? State legislatures?

Prognostications

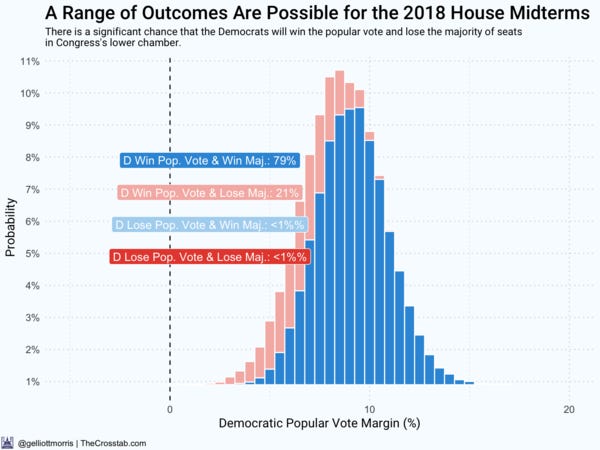

The discussion above sets the stage for the 2018 midterm elections. Great — but what actually transpires on that stage is what really matters. Across the country, Democrats will be challenging Republicans for control of various levels of government. Our House forecasting model at The Economist thinks that one of the patterns above — or an unforeseen one — will deliver the House to Democratic hands 86% of the time — about 5 trials out of 6, or the chance that you roll a die and get a 1.

At the Senate level, Nate Silver reckons that Democrats have a 14%, or 1-in-7, chance of winning control of the chamber. Why? You’re likely familiar with this story by now; Democrats are defending a high number of seats they won in red — sometimes very, very red — states in the 2012 midterm elections. Back then, the political environments in the various states were much more favorable for candidates with a (D) next to their name. Since North Dakota’s Heidi Heitkamp has trailed in 8 of 10 polls taken in the state, according to 538, it’s likely that she’ll miss out on another term. This means Democrats have to pick up an extra seat to win control of the upper legislative house—a total of three pickups instead of two (they’re currently at 49 seats, and only getting to 50 would leave Vice President Mike Pence with a tie-breaking, reliably Republican vote, so they need 51 for a majority). Democrats could win in the vulnerable currently Republican states of Arizona and Nevada and still need victories for either Beto O'Rourke in Texas or Phil Bredesen in Tennessee — events which only have 1-in-5 or roughly 20% chances of happening individually.

At the state level, Democrats look poised to flip 7-8 governors mansions, according to me and my colleague’s work, and ~500state legislative seats (or 7 chambers), according to political scientist Carl Klarner. This could position them well to influence crucial policies like congressional redistricting, since most governors will have vetos over proposed map redraws after the 2020 census and subsequent reapportionment. Democratic victories would mean fewer gerrymanders.

But as an SNL skit made clear on Saturday night, Democrats aren’t taking this year’s forecasts for granted. It might be a happy consequence of the failure of many media types to properly evaluate our quantitative predictions in 2016 that they might better understand uncertainty this time around.

Different outcomes and their pre-postmortems

Let’s discuss the most likely outcomes and the reasons why they might come true.

Scenario 1) Democrats win the House because Obama-Trump voters came home. In this outcome, Republicans lose the ten seats that they’re currently forecast to lose in the Midwest, as well as thirteen others around the country, because voters who switched from Obama to Trump have reverted back to blue, likely as a result of Republican efforts to deprive them of health benefits in mid-2017—efforts that were later revealed to be a first step to the party’s full eventual repeal of Medicaid. The average voter in these districts was also slightly whiter, more educated, and female than they were in 2016, helping Democrats make up ground that they lost when “working class whites” (voters primed with racial animus) came out in droves for Mr Trump. This reversion to 2012 doesn’t help Senator Heitkamp enough to win in North Dakota, and Democrats win 49 or 50 seats in the Senate.

Scenario 2) Suburban White women really drive a Whole Foods revolt against POTUS in suburban America. In this case, the famous “Year of the Women” comes to fruition among the mass public (as well as among Democratic candidates) and causes the blue wave to wash over just shy of two dozen House districts in suburban America. Women, asked by exit pollsters why they (A) voted (B) for Democrats cite president Trump’s moral impropriety as the main reason. In well-educated red seats, a nontrivial number of white Republican male #NeverTrumpers are swayed by their wives and vote Democratic, handing Democrats a few extra pickups and the House majority. However, the inverse trend was observed in rural America; white men — especially those without college degrees — voted at higher than normal rates in rural America, claiming Heidi Heitkamp and Claire McCaskill as casualties of a continual realignment of the Senate to presidential voting patterns.

Scenario 3) Nonwhites fail to materialize in the South and West, non-college educated whites are motivated by late-breaking identity politics. In this scenario, Democrats win in most of the suburban House districts in which they are favored but fail to have received a necessary swell in turnout among liberal whites and low-propensity turnout Hispanics in California and Florida, landing them at either a bare minority or majority. They might have power, but either way, have little more room for affecting Washington policy than they used to — a (moral) loss in the House is compounded by losses in Arizona and Nevada actually expands the GOP majority in the Senate.

Scenario 4) The left tail of the distribution happens. In this scenario, polls have been underestimating enthusiasm for Democratic candidates among nonwhites and young voters across the nation. Finally, it seems, millennials are turning out — to the dismay of many pollsters’ turnout models that failed to account for this possibility. Democrats sweep suburban and urban districts, many with sizable university populations, and in AZ, NV, ND, and TX to capture control of the Senate. This is the “nobody saw this coming!” event, although both scenarios had about a 1-in-10 chance of happening.

Scenario 5) See section below, titled “Is the future the past? Polarization and negative partisanship.”

Scenario(s) 6+) Something else? The mixture of intertwined — sometimes more than others — Demographic and political covariation hurts our ability to really imagine what some electoral scenarios look like. It’s distinctly possible that the actual outcome isn’t yet on our radar.

Is the future the past? Polarization and negative partisanship

Finally, I fear that I have not discussed enough the reasons for why we got here, why the midterms are competitive how and where they are. Let me remedy this issue presently. A fifth explanation for the midterms.

Primarily, I attest that that the most profound trend in American politics today, that of political polarization, largely because of a rise in negative feelings, or affect, for the other party (dubbed negative partisanship in political science literature), explains well why we see the midterms electorate that we see today. Because voters increasingly view the opposing party negatively, they are less and less likely to vote for Republicans if they’re a Democrat (or Democrats if they’re a Republican). This has decreased the rate of split-ticket voting, explaining an increase in the ability to predict House and Senate elections with presidential vote shares for the corresponding geographies. These problems are only compounded by the tendency for voters to stay in media echo chambers, associate mostly with members of their own party (or go bowling alone).

This means that we should expect, over time, that the the 25 House districts that voted for Hillary Clinton and a Republican House representative to switch hands from red to blue. The reverse is true as well; we should expect the 12 Trump-Democratic districts to flip toward Republicans. Of course, there are many other factors at hand in deciding this year’s elections — I’m just explaining a tangible effect of negative partisanship and polarization. But it’s no coincidence that of these districts, 2 Trump-Democratic districts are projected to flip to Republicans on Tuesday and 18 Clinton-Republican districts are favored to go the other way.

It is worth noting how this is accomplished. As Americans increasingly sort into their own partisan bubbles, decreasing the amount of the time spent across the aisle, margins of victory are going to get both slimmer and more stable as elections take place closer to the political equilibrium. However, the closeness to that equilibrium depends on voter engagement and turnout. If one party is more motivated than the other to turnout to vote, the party on top is going to see a boost in vote share that is bigger today than it was in, say, 1990, just because more of their voters are locked in. And because true independent voters make up a relatively small share of the population, these disparities in turnout, a big driver of the purported “blue wave” in 2018, will also slowly become big prizes for electoral campaigns in America. As strategists turn toward efforts to turn out their base, a lack of persuasion campaigns will likely only exacerbate the issue, reinforcing the broader trend of polarization. (Tangentially, I must note that this trend is complicated by the fact that Democrats also have a built-in advantage if more voters turnout overall, due to there being more Democratic than Republican voters in America.)

I highlight this partisanship and polarization argument as both (A) a prospective explainer for a trend we’re seeing this year and (B) a theory for what we might come to see in politics in the future. I look forward to testing this theory over time, but it’s worth pointing out that this year’s midterm elections are being well-forecast by historic “fundamental” indicators in US politics — all of which have been influencing election outcomes prior to our current state of hyper polarization — contrary to what some people may argue.

Where to next?

It is most likely that America wakes up Wednesday morning with a Democratic House and Republican Senate. In this case, Democrats will likely immediately invest committee staff in issuing subpoenas and initializing investigations to provide much-needed oversight of the Trump Administration’s massive, currently under-checked federal government. They will be forced to work on moderate policy proposals that have a chance of making it through a GOP-controlled Senate and past the president’s veto. However, a group of progressive Democrats will probably demand attention for liberal causes, and continually introduce bills to expand Medicare for all Americans, decrease military funding, raise taxes on the super-wealthy and reign in corporate greed. In other words, don’t expect the proposal agenda to deviate that much from predictions based on ideology just because the voting agenda is cause for pause.

However, this is by no means the only plausible outcome.It takes no stretch of the mind to imagine a November 7th in which Trump and Republicans are emboldened by a surprise win in the House and the subsequent disappearance of many moderate members of their party. Conservative lawmaking can now begin again at a pace accelerated by the absence of maverick troublemaker John McCain. Indeed, now that Kevin Cramer is the Senator from North Dakota, Republicans can afford defections from the Liberal Left’s shadow GOP lawmakers, Senators Murkowski and Collins. A new conservative movement is born in America. This is a distinct possibility, however impractical.

Still, there’s the under-discussed fact that a Republican victory in the House is virtually assured to arise out of a Democratic victory in the popular vote. This would mark an unbridled assault on small-“d” democracy in America, the cementing of minority rule at every level of the federal government. The greatest liberal experiment in the world would be cast into a political, constitutional crisis unmatched in modern US history.

(As of 3 Nov. , 3:00 AM — likely to change slightly before Tuesday, 6 Nov.)

~ ~ ~

As I close out this piece, my final forward-looking one on the 2018 midterms, I am struggling coming up with points I think we haven’t discussed. That’s good! Many people have contributed to a conventional wisdom that is well-informed about the possible range of outcomes for this year’s midterms — one that has had plenty of data to back up our findings. This is a welcome improvement over the 2016 presidential election, when some poorly calibrated forecasts combined with a media bubble that, after hours, was so opposed to Trump that biases crippled the chance of well-informed coverage at the tippy-top of journalism. This year is different; We have a wealth of district level polling, thanks in large part to the great “live polling” project headed up by Nate Cohn at the New York Times Upshot, and great House, Senate, and Governors forecasts thanks to FiveThirtyEight, The Weekly Standard, Decision Desk HQ/0ptimus, and of course our own work at The Economist.

The proliferation of probabilistic election forecasting is good for the public’s understanding of elections. Given that the alternative is typically scattered shoutings of polling toplines without (or even with!) margins of error, it seems blatantly clear to me that this is the case. Of course, some research finds (muddied) evidence for the thesis that forecasts decrease voter turnout — so there could yet be some downsides. But I’m confident that our broader work forecasting is “worth it.” If you’re reading this word, the 3,300th of this piece, I think you do, too.

Whether or not probabilistic forecasts do a “good” job this year, election analysts will be back next week with reports similar in statistical approach to debrief the awaiting reader. If you think the forecasts are worthwhile, you might as well hear out our other work. Much — maybe most — of the time, explaining is more illuminating to predicting anyways.

What follows is the usual roundup of data & goodies. Cheers — here’s to a fun final 40 hours of the midterms!

Political Data

Who’s ahead in the mid-term race - The Economist mid-term forecast

Tap here to see the interactiveOverall chance of winning a House majorityUpdated November 02, 2018

Democrats86% chancearound5 in 6around1 in 6Republicans14% chanceDem 86% chance around5 in 6Rep 14% chance around1 in 6This is a new version of our model, incorporating newly-available district-specific data. Read about the changes here.

How to forecast an American’s vote

Upgrade your inbox and get our Daily Dispatch and Editor’s Picks. AMERICA’S FOUNDING FATHERS envisioned a republic in which free-thinking voters would carefully consider the proposals of office-seekers. Today, however, demography seems to govern voters’ choices.

How Are The Early Voters Voting?

The fact that self reported identification better categorizes votes for Republicans and Democrats reflects the fact that voter file data is often noisy.

wthh.dataforprogress.org • Share

SurveyMonkey public opinion poll: Which issue matters most to Americans?

Welcome to SurveyMonkey’s weekly update on the issues that Americans say matter most. Our surveys ask Americans, “which one of the following issues matters MOST to you right now?” We post weekly results here every Thursday.

Election 2018: The Races to Watch and How to Follow Them

On Tuesday, voters head to the polls with control of Congress at stake, and Bloomberg News will be mapping real-time results. The biggest question of the 2018 midterm elections is if Democrats can gain the net 23 seats they need to take the House.

How Two Congressional Races Show What’s At Stake in the Midterms

In the reddest parts of upstate New York, Trumpism is on the ballot. Two congressional races in upstate New York reflect a national trend of insurgent politicians challenging Republican and Democratic power structures in the Trump era.

The early vote suggests minority turnout will be high in 2018, but so will turnout among whites

This post is part of Mischiefs of Faction, an independent political science blog featuring reflections on the party system.

Democrats Can Get Close To A House Majority With Suburban Seats Alone

This entire election cycle we’ve heard (and even written) that the Democrats’ path to a House majority may lie in the suburbs.

Trump Knows Digital Ads Work. Why Don’t Democrats?

The party’s campaigns are ignoring obvious opportunities to engage with voters. Mr. Collins is a board member at Tech for Campaigns.

What a Republican Hold in the House Might Look Like

As we move toward the close of this election cycle, impending control of the House of Representatives remains up in the air. The general consensus among analysts is that Democrats are the favorites, perhaps by a substantial margin, but that Republicans remain in the game.

www.realclearpolitics.com • Share

When the polls close on the midterm elections this coming Tuesday night, the country will turn its temporary attention towards understanding what happened. The winning and losing candidates will likely be clear. However, the “how” a candidate won, or the “why” a candidate lost will not be.

Exit pollsters make changes after 2016 breakdown

The much-beleaguered and always-in-demand election-night exit polls are getting a makeover for 2018.

Early vote totals in at least 17 states already surpass 2014 turnout

Americans have already voted in record numbers in many states in this year’s midterm elections, confirming the heightened interest in the fight for control of Congress and state houses playing out indozens of bitterly contested races.

www.washingtonpost.com • Share

Record turnout? Not for millennials — just a third say they'll vote.

That number has remained steady since August, according the results of a new NBC News/GenForward survey. About a third of millennials say they will definitely vote in November, according to results from a new NBC News/GenForward survey of millennials ages 18 to 34.

CAMBRIDGE, MA - The Institute of Politics (IOP) at Harvard Kennedy School today released the results of their biannual survey of 18- to 29- year olds showing that young Americans are significantly more likely to vote in the upcoming midterm elections compared to 2010 and 2014.

Democrats bank on female voter surge to flip the House

STERLING, Va. — If Jennifer Wexton and fellow Democrats ride a midterm “blue wave” to take back the House, it’ll be in swing districts like this one — and in large part because of the women who showed up last weekend to canvass for her.

Democrats' big challenge: White men without college degrees

Republicans are facing a serious loss of support from women voters in the midterm elections, but the Democrats’ biggest demographic challenge has been building for more than a decade: they’re rapidly losing support from white men without college degrees.

What If Only Men Voted? Only Women? Only Nonwhite Voters?

Imagine if only one group of Americans cast their ballots this November.

Other Data and Cool Work

What the 2018 Campaign Looks Like in Your Hometown

With a few days to go until the midterm elections, campaigns across the country are making their last push to sway voters on Tuesday. But the dominant themes of election ads that voters have seen on television look very different depending on where you live.

Perhaps a nation of immigrants no longer

As the Central American “caravan” of would-be immigrants moves slowly through Mexico, opinions about immigration remain polarized, with Republicans in the latest Economist/YouGov Poll rejecting any US responsibility in helping those fleeing violence, poverty and even religious persecution.

Political Science & Survey Research

Congress Has No Clue What Americans Want

People in the U.S. House and Senate have wildly inaccurate perceptions of our opinions and preferences. Mr. Hertel-Fernandez is an assistant professor of public affairs at Columbia University. Mr. Mildenberger and Ms.

Happy to share my #APSA2018 collaboration with @LilyMasonPhD: Lethal mass partisanship: Prevalence, correlates, & electoral contingencies. We theorize partisanship's lethal potential, then measure lethal views in two national polls. Comments welcome!

https://t.co/9noEl4Tyzg https://t.co/vnkoB5Mv1W

6:20 PM - 24 Aug 2018

What I'm Reading and Working On

Election stuff… lots and lots of election stuff. Visit to my Twitter feed on Tuesday and you’ll see!

Thanks!

Thanks for reading. I’ll be back again next week! In the meantime, follow me online or reach out via email. I’d love to hear from you!

A Special Thank-you Note to Patrons

My weekly newsletter is supported by generous patrons who give monthly to my blog, including these individuals who have pledged especially charitable contributions:

Michael Michael Michelle Mike Mike Monty Morris Nadia Nathan Nicholas Nicholas Paula Robert Robert Ryder Sam Sara Sen Shankar Spenser Stepan Stephanie Steve Steve Steve Suzanne

Sydney Taegan Tamara Tera TheMidpod Thomas Thomas Timothy Todd Tom Tri Tyler Matt Spain Andrew Ben Bob Brett Charles Chelle

Like the newsletter and want to help keep it going? Subscribe today on Patreon for access to private posts and other perks.