The Crosstab Weekly Newsletter 📊 December 23, 2018

What we learned in 2018. + turnout in the midterms, the shutdown, 2020 looms

Welcome! I’m G. Elliott Morris, data journalist for The Economistand blogger of polls, elections, and political science. Happy Sunday! Here’s my weekly newsletter with links to what I’ve been reading and writing that puts the news in context with public opinion polls, political science, other data (some “big,” some small) and looks briefly at the week ahead. Let’s jump right in! Feedback? Drop me a line or just respond to this email.

This newsletter is made possible by supporters on Patreon. A special thanks to those who pledge the top two tiers is written in the endnotes. If you enjoy my personal newsletter and want it to continue, consider supporting it on Patreon for just $2.

This Week's Big Question

What did I learn in 2018? The best books I read:

You can read this on my blog, too.

Last winter, I wrote a quick blog post of the best books I read in 2017, a short list that really was inclusive only of the best texts from that year. This time, I’m writing you a longer list — about 30 books that I read this year and would recommend, excluding only those unnamed books which I wouldn’t. Take your pick, they’re all fantastic.

This year was a hectic year, to say the least. As I tweeted recently, it was a good year “to turn off cable news and open a book.” With the 24-hour news cycle ballooning into a never-ending stream of “POTUS just did X” and “here’s what so-and-so believes about Y,” it’s easy to get caught up in the events that don’t inform us and those that don’t matter at all. Books can help steer us back on course. Tangentially, I’d argue that the crisis of US political punditry is probably due to a lack of political science and history knowledge, and (good) books offer a great remedy. So too have I found solace in longform journalism and magazines, but I might be biased to the latter.

I enjoyed many books this year, from those about identity politics to political revolutions to LSD and psychedelics. Perhaps my humble recommendations can serve you well also. Here’s a list of the 30 books I read this year that I recommend to you all, and a few sentences about each.

(US) Politics (and political science)

How Democracies Die, Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt. Levitsky and Ziblatt’s book is perhaps the best single text we have for understanding how democracies have collapsed elsewhere, and how current events in the US are and are not tracing that path. The discussion of how politicians can erode democracy not by breaking the law, but by discarding centuries of norms is especially prescient.

Uncivil Agreement: How Politics Became Our Identity, Lilliana Mason. Mason’s book espouses how parties have come to represent the near totality of Americans’ social identities, with voters “sorting” into either party based on their race, religion, culture, etc. Our attachments to partisan labels have become identities in their own right, forcing voters to think of electoral losses as zero-sum victories for the “other,” with no reward for “us.” I couldn’t do it justice even in a few pages of text; you have to read it.

Identity Crisis: The 2016 Presidential Campaign and the Battle for the Meaning of America, John Sides, Michael Tesler, and Lynn Vavreck. If you were wondering why Donald Trump was able to consume the Republican Party, the answer lies in the phrase “white identity.” The story of the 2016 election, as Sides, Tesler, and Vavreck write, is of whites’ perceived status threat from their nonwhite neighbors — and of Trump’s acute activation of what poli sci has termed “racial resentment.” This is my preferred book to help understand the political psychology of the 2016 election.

The Great Alignment: Race, Party Transformation, and the Rise of Donald Trump, Alan I. Abramowitz. Speaking of consuming the GOP, Abramowitz has an excellent text of how Donald Trump is a result of long-term trends in partisan polarization that have seen social identities come to justify partisan behavior. It’s a short and lucid analysis of our current political climate — rather, crisis — and helpfully offers some advice for a better future. But party polarizations is likely here to stay.

Political Tribes: Group Instinct and the Fate of Nations, Amy Chua. Speaking of party polarization, Chua has an excellent medium-length book that helpfully offers some sociological context to our current hyper-polarized nation. We’ve dissolved not only into political camps, but also tribal social ones. Importantly, I got from Chua’s book a sense of how identity politics and ideologies like white nationalism reinforce themselves, how we got here, and where we may go — an answer which probably involves cutting out the negative influences of perpetual flag-raising media types such as Tucker Carlson.

The Polarizers: Postwar Architects of Our Partisan Era, Sam Rosenfeld. Importantly, political polarization is not (only) the fault of voters. Elites who rattle their sabers and demonize the other side bear much of the blame and Rosenfeld discusses their catalyzing influence brilliantly. Importantly, he also shows how the rise of partisan polarization was a natural response to many features of our current political system. Where we go from here is up to leaders who want to seek proper solutions to extremized out-party resentment.

Unstable Majorities: Polarization, Party Sorting, and Political Stalemate, Morris P. Fiorina. Fiorina’s contribution to our current state of partisan polarization and social sorting revisits some of his classic work on divides in policy preferences and adds a very insightful discussion of electoral and institutional consequences. While I still think that scholars such as Fiorina and Abramowitz are talking past each other on partisan and ideological polarization (one of the reasons I so enjoyed Mason’s Uncivil Agreement is because it offers an underlying theory of identity-based polarization that addresses both of these patterns), I think Fiorina hits the nail on the head here with his identification of the real pattern shaping US politics today: referenda on the party in power. With voters growing more and more dissatisfied with their choices of candidates in both parties, a pattern of unstable divided governments — and gridlock — have dominated (and will continue to dominate, I reckon) American politics since the 1990s.

The Party’s Primary: Control of Congressional Nominations, Hans J. G. Hassell. If Rosenfeld argues that polarization arose naturally (sort of) out of a decline in the power of political parties, Hassell might say their decline is partially overstated. Through an excellent analysis of primary campaign donors, Hassell convinced me effectively that who “the party” supports almost always wins, at least in congressional nominations. The obvious caveat? Donald Trump was not, in December 2015 or February 2016, arguably, the Republican Party’s nominee. Perhaps theses of the declining influence of parties in candidate selection rely too much on this latter fact, and not enough on the former.

Why Parties?: A Second Look, John H. Aldrich. Speaking of parties, what good are they? Aldrich revisits his original thesis that parties help solve fundamental problems in democracies — how to make rational choices, mobilize voters, and govern majorities among them — and concludes that some weaknesses of our two-party system (see: ideological polarization) are the result of party activists and consistent with former theories about voters’ decision-making.

Red Fighting Blue: How Geography and Electoral Rules Polarize American Politics, David A. Hopkins. There are certainly other reasons for partisan polarization than Aldrich’s theories of party activism, however. Hopkins makes the case in Red Fighting Blue that social issues and electoral institutions themselves have developed and reinforced political divides in America. As a result, much of the country is safe territory for either party, with rural areas increasingly leaning right and more urban ones leaning left.

The Left Behind: Decline and Rage in Rural America, Robert Wuthnow. A qualitative-first analysis attempting to answer the question of why so many rural Americans are filled with rage, Wuthnow draws on public opinion polls and primary accounts to paint a well-developed picture of the psychology of angry rural voters. America has largely moved beyond coal mining, increasingly used automation to replace workers at factories, and moved beyond an economic reliance on agriculture. These are the economic forces shifting wealth to sub/urban America, and those who cannot (or are not willing to) adapt are “left behind.”

Dopesick: Dealers, Doctors, and the Drug Company that Addicted America, Beth Macy. We can’t have a conversation about rural America without talking about the opioid crisis, and Macy’s book offers a lot of information about the “how?” and “why?” of that crisis that I didn’t know before. Plus, it’s an excellent read.

Deep Roots: How Slavery Still Shapes Southern Politics, Avidit Acharya, Matthew Blackwell, Maya Sen. Of course, an analysis of rural (and largely southern) politics also have to discuss the politics of race, and these authors deliver a spectacular one. I especially liked the methodological tools used in this text, which enables a successful argument that the 1870-1970s American South was a place where whites endeavored, at all socially acceptable costs, to deprive blacks of political, economic, and cultural rights. Those efforts persist through this day, and areas of the US that had a higher concentration of slave-owning whites still have a higher proportion of left behind nonwhites.

The Turnout Gap: Race, Ethnicity, and Political Inequality in a Diversifying America, Bernard L. Fraga. Fraga’s book is one of my top five from this year. It offers a methodologically sound and compelling argument for why nonwhites — especially Hispanics — turn out to vote at lesser rates than whites. Many campaigns don’t value those voters — or at least, don’t communicate their actuarial assessments of their value effectively. Fraga’s analysis puts a lot of egg on the face of scholars who argue that voting is only an individual choice, and I have to say, I love a good contrarian argument. Especially when it’s the correct one.

Uninformed: Why People Seem to Know So Little about Politics and What We Can Do about It, Arthur Lupia. Speaking of voter engagement, many, bluntly, know little to nothing about politics. Low-knowledge voters dominate America. Why? And how do we fix that? Lupia places a lot of blame on educators — teachers and activists mainly, he says (and, I think, at least in America in 2018, parents and journalists) — and proposes a key strategy to informing voters and getting them involved: personal connections to issues. For example, it’s more persuasive to show Miami residents the personally observable result of climate change in their flooding streets than making them watch a presentation. Making politics personal is a key path to getting more Americans involved.

Prototype Politics: Technology-Intensive Campaigning and the Data of Democracy, Daniel Kreiss. The 2018 midterms showed that campaigns harness technology for almost every aspect of the race. With digital technology comes a host of data that campaigns can harness for deriving insights about their methods. Kreiss’s book gives you an informative, deep dive into how campaigns use this data.

Hacking the Electorate: How Campaigns Perceive Voters, Eitan D. Hersh. On the topic of data in politics (my favorite!), Eitan Hersh’s now-old but new-to-me book Hacking the Electorate gives you a thorough look at how voters target voters and what data they use to do so. It’s not the commercially available data that is the secret sauce to effective targeting, Hersh’s analysis suggests, but the publicly-available records of voting behavior.

Delivering the People’s Message: The Changing Politics of the Presidential Mandate, Julia R. Azari. Azari is one of my favorite political science bloggers, offering up timely and insightful works about politics at what seems to be a super-human pace. This book is no exception. Arguing that polarization and popularity influence how presidents invoking the rhetoric of mandates, decreasing use when the former is low and latter is high and increasing use otherwise, Azari forms a convincing theory of mandate rhetoric over time that also explains its recent meteoric rise.

I recommend two well-known books about American international relations: A World in Disarray: American Foreign Policy and the Crisis of the Old Order, by Richard Haass, and War on Peace: The End of Diplomacy and the Decline of American Influence, by Ronan Farrow, which both show the failures of US foreign policy to adapt to important issues in politics both global and domestic. The result is an America of declining influence on the world stage.

The Red and The Blue: The 1990s and the Birth of Political Tribalism, Steve Kornacki. Kornacki’s book is a history of polarization and tribalism in America, tracing the political roots of Gingrich’s 1994 Republican Revolution and his weaponization of partisan politics to their first events. If you want to understand how we got here, this is a great stop along your intellectual journey.

History

Nation Builder: John Quincy Adams and the Grand Strategy of the Republic, Charles N. Edel. Nation Builder as an excellent biography of JQA’s life and an even better explainer of his “grand design” for the nation. Adams’ famous warning against an activist foreign policy, “America goes not abroad in search of monsters to destroy,” was just the tip of the iceberg of his vision for the country, both at broad and at home. One must not forget the story of Adams’ death: suffering a stroke on the floor of the House of Representatives after arguing fervently against a vote on a resolution to the Committee on Military Affairs, Adams died two days after.

T.R.: The Last Romantic, H. W. Brands. This long biography of Teddy Roosevelt (another by a former professor of mine) is quite old compared to the others on this list, so chances are you may have already read it. An investigation into Roosevelt’s full life that rivals the quality and length of Ron Chernow’s Washington: A Life, a favorite read of mine.

Grant, Ron Chernow. Chernow’s excellent biography of Ulysses S Grant — from his origin through military accomplishment to underrated presidency — rivals his other best-selling works on George Washington and Alexander Hamilton. In typical Chernow style, the text is exhaustive, meaning you’ll learn everything you have ever wanted to know about President Grant, but you’ll spend due time (over 1000+ pages) doing so.

Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution, Simon Schama. In a sentence, Citizens is the best history of the French Revolution that I’ve come across (though my reading is by no means exhaustive). It explores all angles of the Revolution with a vast cast of characters, and perhaps come closer to encyclopedia than a novel. For that, I’d recommend Hillary Mantel’s novel A Place of Greater Safety

Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787-1788, Pauline Maier. Maier’s text is a documentary history of the creation of and reaction to the United States Constitution, which enjoyed a very tumultuous and near-failing ratification process throughout the colonies. Through letters from Founders both prolific and less known, we already know the story of the Convention itself. Maier’s history takes us into the taverns, homes, and inns of America. Writings by “everyday” Americans offer a helpful lens into a governing document whose meaning still hotly debated to this day.

The Framers’ Coup: The Making of the United States Constitution, Michael J. Klarman. Did you know that the Constitution says the word “liberty” once and “power” seventeen times? How can that be, when the Revolution was borne out of a desire for freedom from a strong governing authority? Klarman espoused the counter-Revolutionary ideas present in the constitution and tells of the struggles that elite pro-government Founders such as Hamilton and Madison had at mustering countrywide support for the agreement. Klarman posits that such an agreement was passed not by pulling at the heart-strings that spurred on a successful revolution, but rather, by bringing multiple interest groups to the table through good old-fashioned benefits brokering and power politics.

The Wealth of a Nation: A History of Trade Politics in America, C. Donald Johnson. Among the more intriguing books, I read this year is Johnson economic history of America. It could not be more timely. At a time when the politics of trade are so central to our current discussion about government, this was an extremely useful text. (Admittedly, I skimmed some parts that I ought to go back and re-read.)

Data

The Master Algorithm: How the Quest for the Ultimate Learning Machine Will Remake Our World, Pedro Domingos. Domingos discusses the handful of algorithms that will make up humanity’s eventual artificial intelligence solution, but which current approaches haven’t been able to create. The book is a practical overview that doesn’t contain the mathematics and statistical equations that define them, which is helpful, for those interested in learning about the subject, but not doing it themselves.

The Book of Why: The New Science of Cause and Effect, Judea Pearl and Dana Mackenzie. Running parallel to scientific inquiry into artificial intelligence is how we can make computers answer the question of “Why.” Existing statistical methods all answer “what” questions, like “what’s the correlation between two variables?” But to establish that x event caused y observable outcome, rationality and reason are required. Currently, only humans possess those tools. But can we teach them to a computer?

Other nonfiction

How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence, Michael Pollan. A chart-topper, Pollan’s book is a fascinating journey into the history and science of psychedelics. He painstakingly holds our hand through the people and events that brought the subject into public consciousness and even takes us through his own psychedelics journey. I have no particular interest in the subject but enjoyed the book immensely.

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, Yuval Noah Harari. Another NYT best-seller, Sapiens takes you through the evolution of humanity and the several radical developments that pushed our species forward. First, language and agriculture caused the development of our current species, the Homo Sapien. We’ve come to adopt religions, science, and governments. That’s an incredible transformation from our hunter-gatherer ancestors. How did this happen? I couldn’t put the book down.

…

There you have it, the 30 books that I read this year and would recommend you to read as well. Upon reflecting further while writing this post (which has now gone on far too long, I fear, at 3000 words), I could only come to realize that I read much about US political science and history while lacking in other areas. What books would you recommend in other subjects? Note that I only really read non-fiction, and will probably keep it that way, though have recently made an exception for Tolstoy’s War and Peace. Do let me know — I’d love to hear from you!

Political Data

Who will Americans blame if the government shuts down?

With hours to go before a potential federal government shutdown Friday night over funding to build a wall along the U.S.-Mexico border, President Trump and Democrats are blaming each other for the gridlock.

www.washingtonpost.com • Share

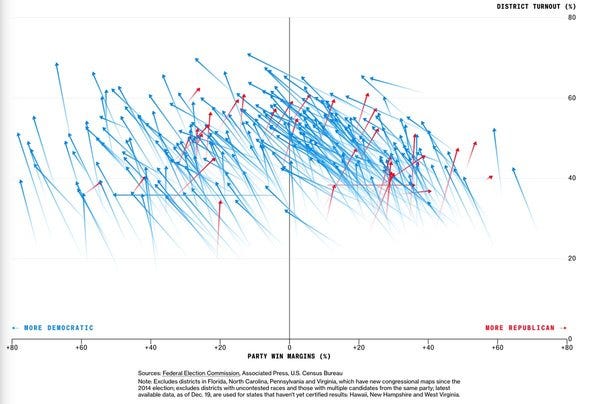

Voter turnout increased in House races across the country from 2014 to 2018, and the vast majority shifted left https://t.co/NUzgyYTX0L

10:08 AM - 20 Dec 2018

America’s Electoral Map Is Changing

Today’s political landscape is often dismissed as a partisan deadlock in which the vast majority of voters have already made up their minds and will only dig their feet in further with each passing news cycle.

A record number of women will be serving in the new Congress

When the 116th Congress convenes next month, women will make up nearly a quarter of both the House and the Senate – the highest percentage in U.S. history, and a considerable increase from where things stood not too long ago.

It’s the populism, stupid. Young or old? Female or male? White, black or Latino? The first stage of the 2020 presidential campaign — the jockeying stage — is underway, and Democrats are trying to figure out who the ideal candidate is.

Donald Trump learned nothing from midterms. Exhibit A: the shutdown. - CNNPolitics

The shutdown may please the base. It looks like a political loser overall, however. Perhaps more worrisome for Republicans, it doesn’t look like Trump learned a single thing from Republicans losing in the midterms.

Other Data and Cool Work

Why 536 was ‘the worst year to be alive’

Ask medieval historian Michael McCormick what year was the worst to be alive, and he’s got an answer: “536.” Not 1349, when the Black Death wiped out half of Europe. Not 1918, when the flu killed 50 million to 100 million people, mostly young adults. But 536.

Political Science and Survey Research

Newly-published paper inquires about the consequences of Donald Trump’s unique propensity to flip-flop, finds that his supporters are more attached to his label than conservatism; will adopt policy preferences if told that he supports them, even liberal ones. https://t.co/b47KzwSDdT

10:16 AM - 19 Dec 2018

In top read paper @tiffanydbarnes and @ErinCassese evaluate how party and gender intersect to shape policy attitudes. Gender differences are more pronounced in the Republican Party than in the Democratic Party https://t.co/08dgoS47t6. Check @LSEUSAblog https://t.co/NMHMXf6iwl

12:00 PM - 18 Dec 2018

What I'm Reading and Working On

I’m taking a break from reading this week to spend time with family for Christmas, though I just put down Ronan Farrow’s War on Peace. I’m working on an exciting project about gerrymandering, the midterms, and the 116th congress… stay tuned.

Thanks!

Thanks for reading. I’ll be back again next week! In the meantime, follow me online or reach out via email. I’d love to hear from you!

A Special Thank-you Note to Patrons

My weekly newsletter is supported by generous patrons who give monthly on Patreon, including these individuals who have pledged especially charitable contributions:

Alden, Ben, Calvin, Christina, Daniel, David, Joshua, Joshua, Katy, Kevin, Laura, Robert, Robert, Thomas, Christopher

Ben, Bob, Brett, Charles, Charlie, Chelle, Darcy, Darren, David, Erik, Fred, Gail, Greg, Guillermo, Hunter, Jay, Jon, Malcolm, Mark, Nik, Nils, Sarah, Steven, Tal, Uri

Like the newsletter and want to help keep it going? Subscribe today on Patreon for access to private posts and other perks.