The Big Lie is the central litmus test for Republicans running for office

The right will have to decide whether It believes in liberal democracy

On December 14th, 2020, the New York Times published a story that posed the question “What’s Next for Trump Voters Who Believe the Election Was Stolen?”

The author, Sabrina Tavernise, wrote “What happens next is a critical question for American democracy. …

What will become of the belief that the 2020 presidential election was in some way illegitimate? Will it melt away along with Mr. Trump’s prospects for winning, and vanish completely when Mr. Biden is inaugurated? Or will it fester, nursed by Republicans in power, and metastasize into something that could be a rallying cry for nationalists for years to come?

It is the perception — often more than the reality — that matters, said Keith A. Darden, a political science professor at American University in Washington. “If enough people believe that a government is not elected legitimately, that’s a huge problem for democracy,” he said.

It is a huge problem in part because it can increase instability and the chance of violence. We saw both come to fruition less than a month after Tavernise’s article ran when thousands of Trump supporters mobbed the US Capitol and staged an insurrection against a government they thought to be illegitimate.1

Upon reading the article, I shared my opinion on Twitter, predicting that the Big Lie would become a litmus test for Republicans running for office in a post-Trump America.2

I wish I had reflected more on this back then. But luckily, people who are way smarter than I continued to write about the issue and jogged my memory.

Today, Jonathan Bernstein has written for Bloomberg View that “fictional election fraud pumps up the base, and that’s all that matters in a policy-free party.” Reflecting on this past weekend’s GOP convention in Utah, where Republican Mitt Romney barely survived a censure vote from the state’s Republican activists, Bernstein says “believing — or at least pretending to believe — Trump’s fantastic lies about nonexistent voting fraud is increasingly the central belief Republican elected officials must share.” He goes on:

My guess is that this has little to do with Trump. Republican complaints about fictional election fraud were central to their legislative agenda in state after state well before Trump’s 2016 campaign. It’s true that the specifics of that agenda have shifted somewhat in response to Trump’s whining. What that shows more than anything, however, is that attempts to hijack elections may only be the secondary motive for these laws; the primary reason for them is for Republican elected officials to convince their strongest supporters that they are doing their best to repress Democrats and various Democratic groups.

That’s why fictional election fraud is such a good issue for many Republicans right now. Opposing Biden and the Democratic legislative agenda, after all, would tend to unite the party. But a united Republican Party is the last thing that Republican radicals want. They need enemies; they need apostates they can label “Republicans in name only” to prove that they are the true conservatives. The Jan. 6 Capitol riot and Trump’s continuing lies are so obviously an attack on the Constitution, the rule of law and the American republic that Republicans such as Romney and Cheney refused to go along. For the radicals, that’s exactly the kind of opportunity they rarely fail to exploit.

Especially after renewed calls from Republican House members to strip Liz Cheney, who voted to impeach Trump for his role in the January 6th insurrection, of her position as the conference chair of the House GOP, it is hard not to see support for Donald Trump and outright opposition Joe Biden’s victory as the key purity test for Republican politicians today.

This past Saturday, for example, we saw a GOP candidate for Texas’s sixth Congressional district surge in the late vote for a special election to fill the seat. Trump endorsed Susan Wright, the wife of the late Congressman Ron Wright, who died after contracting covid-19, a week before the voting. The conservative anti-tax group Club for Growth spent over a quarter of a million dollars on advertisements painting Wright’s main opponent Jake Ellzey as being insufficiently pro-Trump,

The Republican candidate Michael Wood, backed by #NeverTrumper and Illinois Republican House Rep. Adam Kinzinger, placed ninth.

. . .

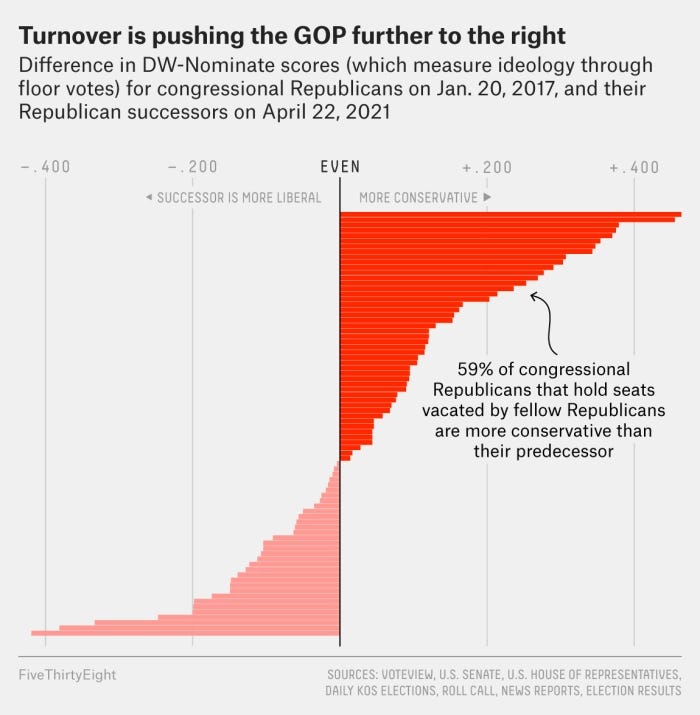

Here’s the data-driven, longer view. FiveThirtyEight recently published an analysis on what I have referred to as “ideological churn” of legislators.3 Over the past twenty years, Republicans, in particular, have been disproportionately likely to be replaced by more ideologically extreme members once they leave office — either voluntarily, or via defeat in primary elections. According to 538, 59% of congressional Republicans who currently hold seats that were vacated between 2017 and 2021 are more conservative than their predecessors:

“Conservative” here is based on an algorithm, called DW-Nominate, that scores each congressperson along multiple dimensions according to how often they vote with the other side of the aisle. But what is ideology, really, when your party has prioritized culture war issues (which often don’t get taken up for votes on the House or Senate floor) over traditional disputes over politics and policy?

Well, between 2017 and 2021, Republican primary fights revolved around an axis of loyalty to then-president Trump. But with Trump out of office, the new axis in GOP primary fights is loyalty to his claims of election fraud.

Take a moment to reflect on what this means. Intra-party competition on the right has shifted from revolving around policy and policy-adjacent issues — particularly, as during the 2010 primary, over government spending, social conservatism, and racial resentment — to whether a person endorses a baseless conspiracy theory that the current president cheated to win the White House. Those on the “right” of the party see voter suppression laws and shadowy recounts as their primary mode of competition against the NeverTrumpers, who call their leader corrupt and deceitful, in the middle.

Given that free and fair elections are a central requirement of liberal democracies, one might restyle this competition to say that many Republicans are now implicitly campaigning against electoral democracy itself. All because the guy who lost told them to make a big fuss about the process that led to his defeat. To one side of the party — the vast majority of it — the only votes that count are ones for Republicans. That’s why we’ll keep seeing recount efforts in, for example, Arizona, where the Republican-led state senate hired a private company to audit the ballots cast in Maricopa County — and why we’ll continue to see Republican Congressional candidates prove their “conservative” bona fides by supporting the former president’s Big Lie.

. . .

I return to two other questions I asked in early January. If America’s two largest parties are now competing — with Republicans on the extreme “right,” and Democrats in the reasonable, classically liberal center — over whether to accept the verified, validated results of a national election, how democratic is the country, really?

And how long can this go on?

I welcome your reflection in the comments.

For those keeping score at home: the fact they believed the government was fraudulent does not justify their action

Not to toot my own horn, but…

Political scientists call this “replacement,” which is a fine noun but simply not as fun

Hi Elliott,

If one of the two major parties doesn't accept the results of a national election, we are democracy? As long as power is transferred successfully, we might be able to call it a failing democracy.

One day, Republican state legislatures will likely overturn a Democratic Electoral College victory. Even if they fail, the chances of political violence is likely. I think Donald Trump's legacy will be destroying confidence in American democracy and the assault on the Capital of the United States of America. Trump's actions makes him the worst President in our history.

-Elliot