The US House majority is not up for grabs

The Democrats are very likely to hold the chamber after November’s elections

I meant to send this out yesterday but something went wrong. I don’t exactly know what, but at any rate you did not receive it on time and I am sorry. Please forgive the late newsletter. I’ll have something extra for you early next week (or maybe tomorrow if I’m feeling productive).

Elliott

Recently I have seen several pretty funky takes that Republicans have a shot at taking back control of the US House of Representatives come November. Several of you have even asked me about this. While I think the data is pretty conclusive (a resounding “no!” is in order) evidently other people disagree. So let me just make this as clear as possible: here are the 3 reasons why Republicans have almost no chance of winning the House majority.

Seat change in presidential cycles is typically very low

Congressional elections that take place in presidential cycles typically result in very low turnover. Just check out this table (which I’ve lifted from Kyle Kondik over at Sabato’s Crystal Ball) that shows net seat change in House elections since 2002:

As you can see, with the exception of 2008 the last 4 presidential-year congressional elections have resulted in net turnover of less than 10 seats. This is likely due to the relative stasis in electoral environments between a mid-term election and the following presidential race, especially when incumbent presidents are up for re-election.

So maybe it helps to think of mid-terms as the odd ducks here; then, the president’s supporters are typically in power and complacent and a backlash against the party in power drives down their seat totals. Republicans would need to pick up 20 seats to win back the House—an Obama-sized wave in their favor. That looks nearly impossible to materialize because….

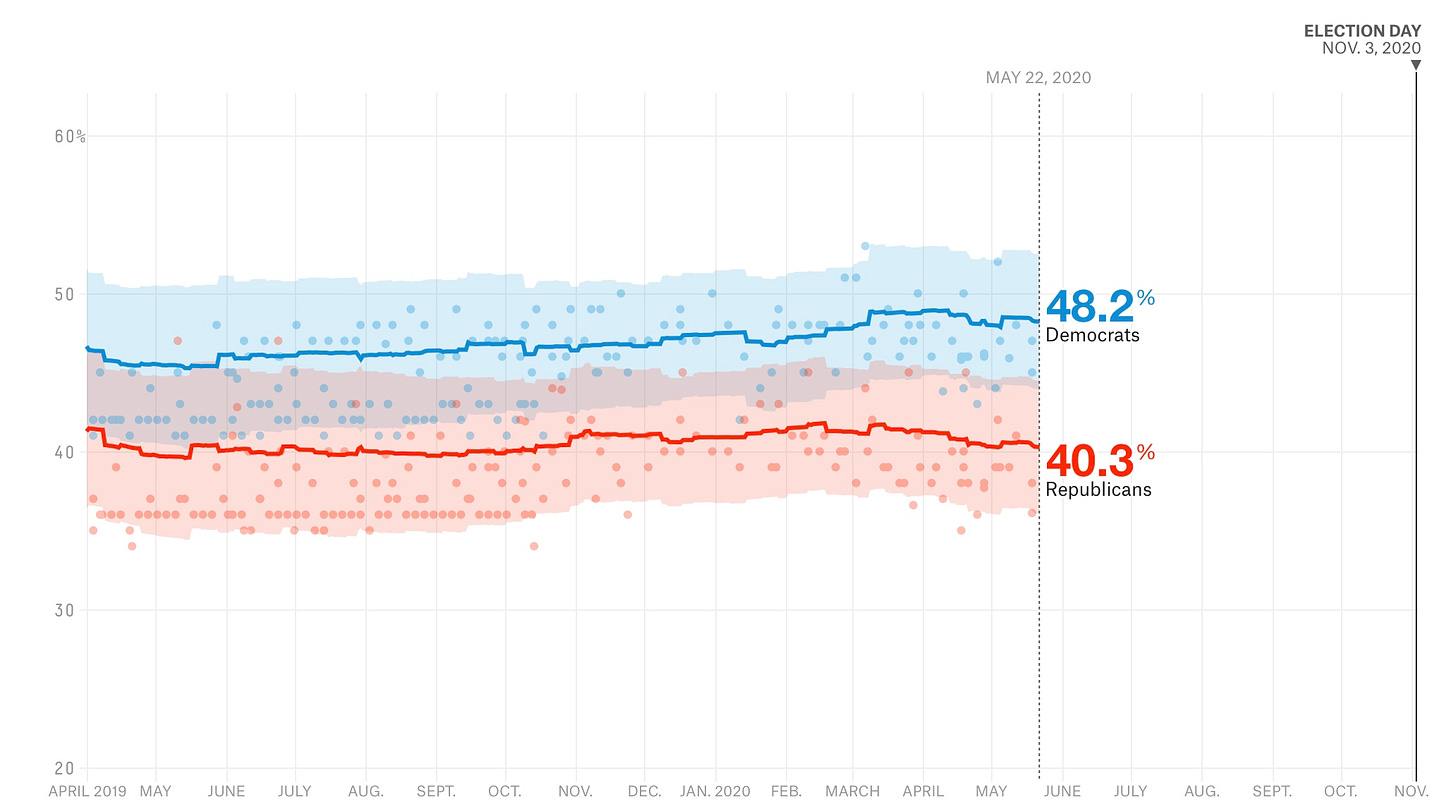

The generic ballot favors Democrats in a big way

The generic congressional ballot—a poll question which asks voters how they’ll cast ballots in their House district—has hovered between D+5 and D+8 for the past year. This evidences the “relative stasis” I mentioned earlier; Democrats won the 2018 House popular vote by about 7 percentage points (once you account for votes that would have been cast in uncontested seats).

The across-year stability in the generic ballot does not bode well for Republicans. Though they have an edge in the House (they won the majority of seats in 2012 despite losing the majority of votes) it is not large enough to topple an 8 or even 5 point deficit. If Democrats are polling similarly to how they performed in 2018, we shouldn’t expect much to change in terms of seat allocation. We know that’s empirically true because of…

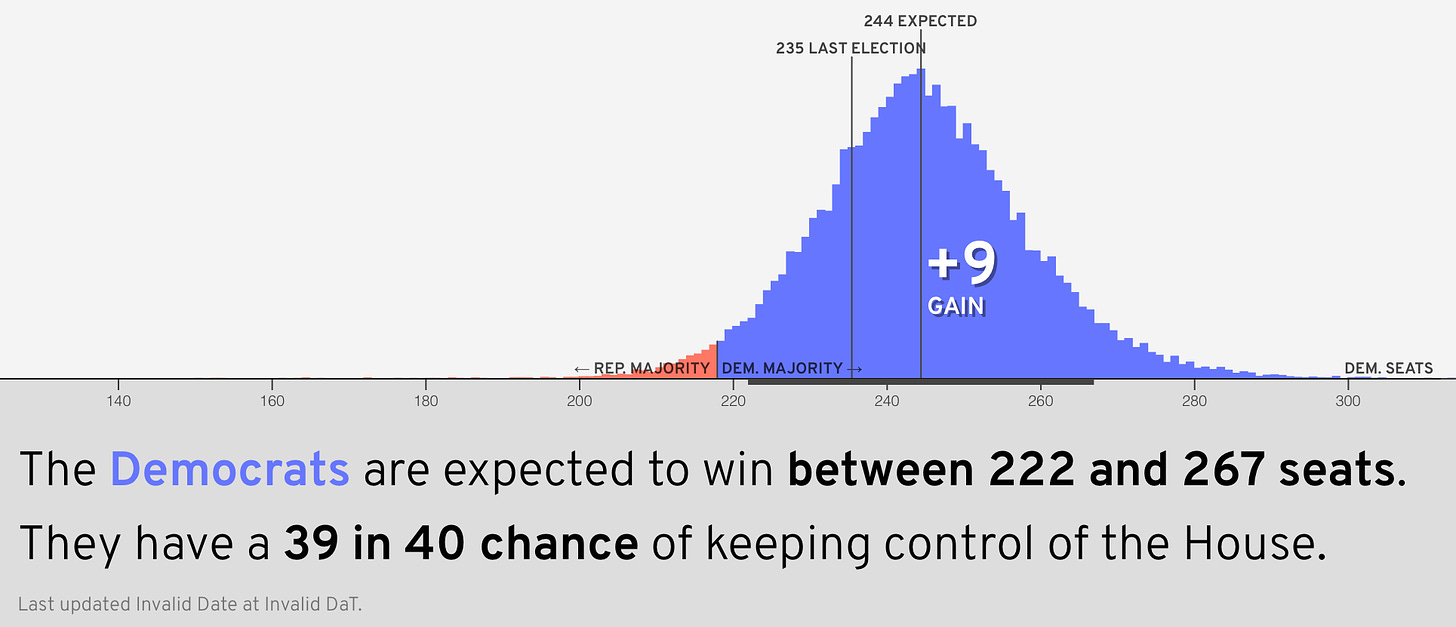

The (good) models give Republicans a rather poor chance

Though they are imperfect, statistical models help us make sense of the world. In the case of elections, properly-calibrated models help us distill all the different indicators of success of failure into predictions of the future.

One US House model I’ve become interested in over the last few months is from Cory McCartan, a Government PhD student at Harvard. His model takes the generic ballot and each party’s performance in previous mid-term elections since 1974 as inputs and spits out the average number of seats it expects each party to win. So far, it is pretty bullish on Democrats keeping their majority:

In sum, if we’re being quants about the House elections, I don’t think it’s reasonable to expect a close race. Indeed, it’s very, very unlikely that Democrats would lose their majority.