Saturday subscribers-only post: Joe Biden, Emmanuel Macron, and the future of the global "Brahmin left"

An election in France shows how American political conflict is part of a broader realignment of the global political system

A long time ago, workers voted for left parties, and capital — business owners and well-paid, educated citizens — voted right. This is how, eg, you got a southern American political system in the 1960s which was dominated by conservative Democrats but had pockets of wealthy liberal Republicans, mostly in cities. And it is how you got socialist and communist uprisings against right- and center-left governments across Europe earlier in the century. In this era, more than anything else, politics was determined by ones’ class.

Of course, this is an oversimplification. But at the very least you can decisively say that things are much different now than they once were. There is a healthy mix of both left-leaning and right-leaning workers, and there are many rich leftists. Americans seemed to fully realize this new political-class system in 2016, when Donald Trump won the presidency largely off the backs of working-class white voters, who had previously supported Democrats, and rich white elites. This Sunday, as France holds the first round of its 2022 presidential election, the country’s voters could also see the effects of this new dimension of global party conflict.

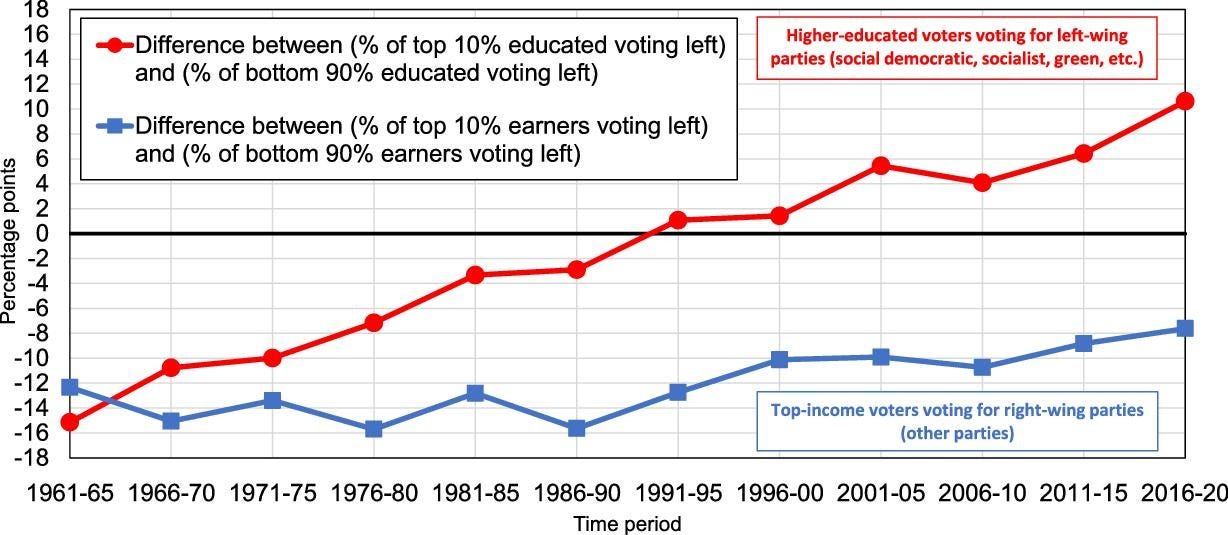

The economist Thomas Piketty traces these shifting political cleavages to the global rise in education polarization — with educated voters increasingly casting ballots for left politicians and those without degrees moving right. In a 2022 paper “Brahmin Left Versus Merchant Right,” Piketty and his co-authors provide the following graph of the voting behavior of high-education and high-income voters in western democracies:

In the 1960s, low-income and low-education workers were united behind left-leaning parties. But over the decades, these parties have come to rely on a union of low-income and high-education workers. Piketty’s “Brahmin left” is led by high-education voters, who have become much more diverse occupationally since the 1960s, lending them broader cultural power and closer affiliation with professionals like professors and journalists who tend to support culturally progressive and economically left-wing parties. The intellectual left has also grown because of globalization and migration, which weakened the class-based coalitions which had previously dominated politics.

At the same time, the low-education (but not necessarily low-income) “working class” of industrial western democracies has ceased to exist. No longer are union workers joined in community on the factory floor, where their interests are typically pitted against capital. The Brahmin-ization of many parts of the global left led right-aligned parties to promise these fractured workers that they would secure them a place in the future of their country; that they would no longer be “left behind” by the cultural powers that be. They have argued that the internationalist tendencies of the global left have led to new parties with no role for nationalist industrialists — parties that price social progressivism higher than economic progressivism.

Of course, this is somewhat of an overstatement of the realignment of global conflict and shifting partisan priorities. The left has no more actively pushed away working-class voters as right parties have reoriented around the politics of cultural conservatism. As Jan Rovny, an associate professor at Sciences Po, Paris, puts it:

The great structural transformation, reflected in the educational flip, resulted in the severing of the ties between the working classes and the parties of the left, leaving these populations in political drift, free to descend towards cultural particularism. … Today, left-wing cultural conservatives, overwhelmingly made up of the new service underclasses, and other downgraded or under-skilled middle classes are indeed politically lonely. Both because almost no one reaches out to them, and because they have no socio-historical affinities with any political family and no mobilisation capacity of their own.

We can see the political reorientation around left-right social values in the latest Global Party Survey, a research collaborative that grades parties on their liberalism across multiple issue areas. Zoom in on France in the following plot. (in the upper right-hand corner) and you will see that the far-right Front National (FN), which is Marine Le Pen’s old party and the most popular right party in the current election, is separated more from Emmanuel Macron’s party, the formerly named “La République En Marche”! (REM), along the social axis rather than the economic axis. The same is true in the United States. (And for the major parties in most other countries on the following plot.)

The success of Marine Le Pen, currently polling at 23% to Macron’s 26% in the first round of the French election, shows how effectively the populist radical right can court working-class voters, which “increasingly proposes to satisfy both their cultural conservatism, as well as their economic protectionism,” according to Rovny.

The similarities between the French and American voters on this front are not hard to spot. Just as Donald Trump promised to address the grievances of (mostly white) “forgotten” Americans, alienated culturally and economically by internationalism and technological advancement which concentrated wealth on the coasts, so too does Le Pen — who claims the “true” French population has been left behind by Euro-centrism and international migration. And yet both hue closer to the classically left positions on economic redistribution than their more traditionally economically conservative opposition.

This may perhaps give America’s left some hope for the future of their country’s politics, which has descended more and more into the realm of unproductive and often backward cultural disputes — on “critical race theory,” same-sex marriage, racial equity, and etc — over the last decade. That the postmaterial era, where more people than ever, across countries, have access to at least the minimum goods and services necessary to survive in modern society, has given rise to a populist right around the globe means their Democrats are not facing threats that are the unique consequences of their failures to deliver for working-class people.

But a victory for Marine Le Pen on Sunday, much like the unpopularity of Joe Biden in America today, would be a sound indictment of the global liberal establishment’s claims that they can effectively provide more returns on governance than the populist right.

The left argues that it is hard to balance the desires of an increasingly non-college-educated class of postmaterial working-class voters and an intellectual class of educated ones. That is probably true. But it does not make their problems any less real. In America as in France, it is unclear if anyone left-leaning has a way to solve that problem.

I'm not sure it's solvable within the current generation of people who predominantly vote. At least in America, where the left would love to deliver economic benefits that would measurably improve the lives of all citizens, including those on the right (build back better).

The left can't and shouldn't deliver what the conservatives really want, which is restoring them to their place of dominance in society even at the expense of vast numbers of the left-leaning coalition (non-whites).

Where exactly are you supposed to compromise your principles - and your own supporters' rights - when reaching out to a group that contains a large number of racists?

The only solution I can see is outlasting them. Enduring another decade or so, I'm guessing, until the continuing depopulation of non-urban areas and the dying of older voters robs them of enough base that even manipulation of the democratic process can no longer save them.

At which point they'll finally be forced to give up on dominance in exchange for receiving better health care, access to child care and elder care, free community college, etc. In other words, their lives will measurably improve (but they'll still complain about it).

I would love to see an analysis of what voting patterns will look like in a decade as the non-white, educated, increasingly urbanized, citizenry continues to age into the voting population.

It was Ronald Reagan who began the policy of defunding public education, substituting public funding for private schools. And I am convinced that both restoring high quality public education and countering the Fox and talk radio propaganda are keys. But primarily the probability is that "civilization" will not survive our destruction of the planet, within 20 years this will all be moot.