Welcome to the blog’s new monthly(-ish) Q&A. Remember that you can submit questions for future editions here.

Readers sent in a lot of great questions to answer this week. I have done my best to select one big topic (on how parties ought to pick presidential candidates!) that I think all readers will enjoy, and picked a few other questions (which today just so happen to be a bit more technical) to put behind the paywall.

If you enjoy this post, please share it!

Doug asks: “After 2020's pervasive 15% threshold nearly preventing Democrats from rallying behind an electable presidential candidate, any serious thoughts about reform before 2028?

This is a good question, and interestingly one of the few backward-looking ones on the submission sheet.

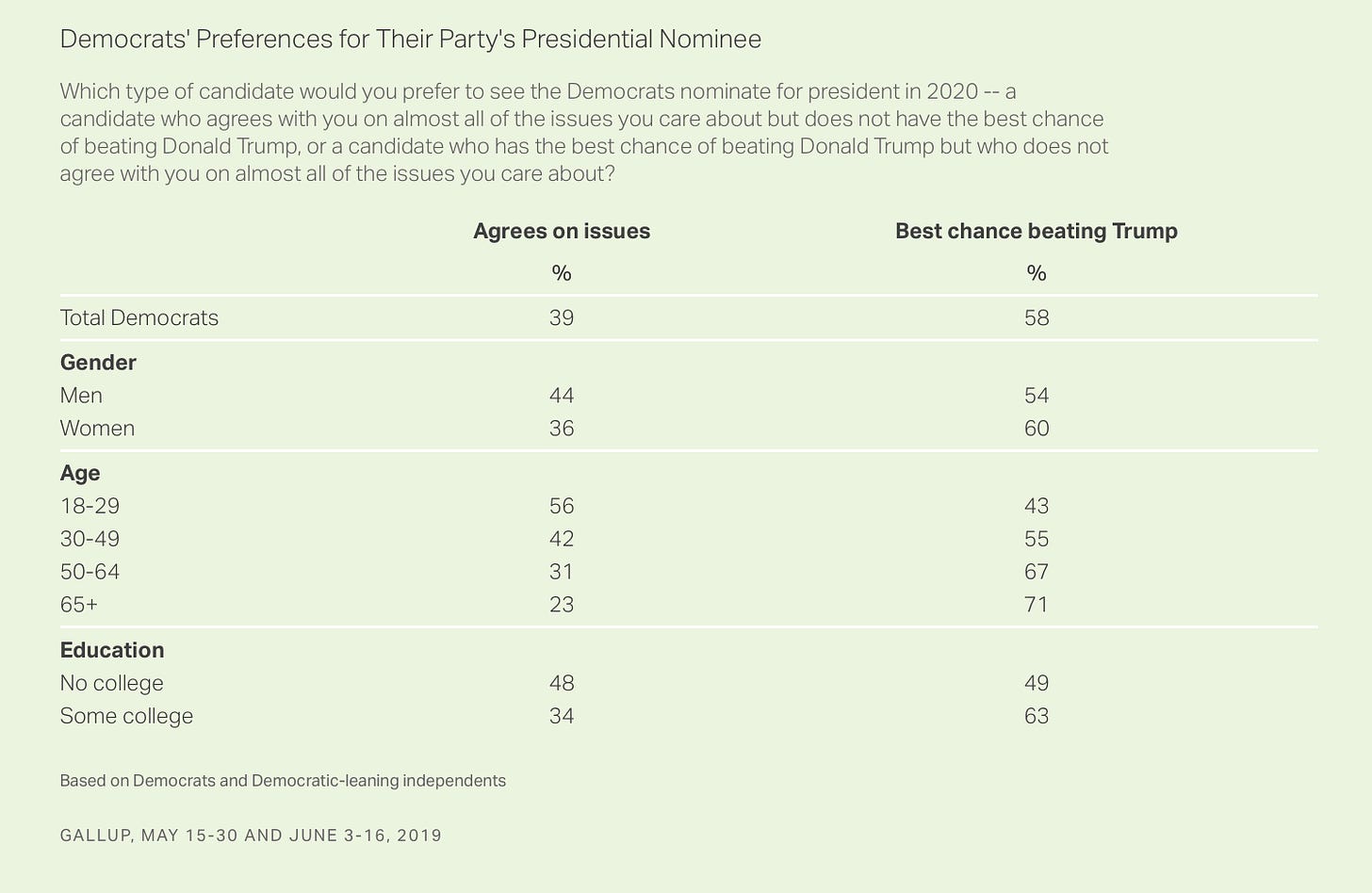

Setting aside what “electability” means or whether we can even directly measure it, what I thought of first was how the 2020 Democratic Primary has a reputation for being atypically focused on electability. But I’m actually not sure that the party is meaningfully more electability-minded than before. In a Gallup poll from June 2019, 58% of Democrats said they preferred a candidate with the best chance of beating Trump over one who they agreed with on most of the issues they care about.

In comparison, the share of Republicans who prioritized electability over issue congruence was 53% for primary voters in 2011 and 55% for Democrats in 2004. Given Gallup’s large sample sizes those numbers are likely statistically significant, but they do not strike me as meaningfully larger than another — eg in terms of whether one candidate would have had a chance in 2004 or 2020, holding everything else about the party and election circumstances equal.

OK, so, Democrats were focused on electability, but maybe not any more than they or Republicans usually are. That makes sense given the degree to which partisans want to avoid victories by their political opponents. About 90-95% of Democrats and Republicans vote for the same party year after year. It is reasonable to think the vast majority of Democrats would have voted for Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren — less “electable” candidates — and, similarly, that Republicans in 2016 would have also turned out at about the same numbers for a Marco Rubio campaign. (NB: One note is that close general elections are fought on those 5-10% margins!)

What’s interesting to me here is how America has ended up with a unique, not-repeated-anywhere-else-in-the-world presidential primary system that somewhat emphasizes the tension between these two qualities (electability and representation) among nominees.

The process (at least on the Democratic side) of democratizing and devolving candidate selection to a proportional popular vote at the state level creates an array of weird incentives acting on voters and candidates. These incentives influence our decisions and, thus, the outcomes we get from the system.

One example comes from the spacing out of primaries across a primary calendar. This causes an overweighting of candidates who perform well among voters in early contests, who tend to be whiter, more educated, and more engaged than Democrats who vote later. And while candidates can overcome this — Joe Biden is arguably president because of good old fashions politicking among African Americans — we can imagine worlds where outcomes are substantially different. So, one idea for reform is to compress the calendar — or just have all the voters cast ballots on a single day.

This is going to get messy when you only have 20 candidates. So the second proposal is to allocate votes to candidates using ranked-choice-voting, rather than assigning convention delegates to them proportionally (and only if a candidate receives more than 15% of the vote). A nationwide primary using ranked-choice voting would have the benefit of balancing better between ideological representation and electability. So long as you think people should be picking party nominees, that would be an improvement over the current system.

There is one outstanding criticism, however. Political scientists and presidential histories have been particularly focused recently on what the utility of democratized candidate selection is, anyway. One theory is that the system makes voters happier with their nominees; with a party primary where delegates are bound to candidates, you never get a Democratic nominee Hubert Humphrey (who did not enter any state primaries before his contentious nomination in 1968).

But democratization may also open the door to polarization and extremism, especially on issues of democracy and electoral liberalism. I am drawing here on an argument made by Elaine Kamark in her book Primary Politics. In democracies overseas, for example, parliamentary leaders are selected by representatives, not voters; then, voters get to cast indirect up-or-down votes for them via the general election process. Kamark proposes a variety of potential reforms, including letting elected representatives nominate the candidates that people then vote on. They act as useful and informative gatekeepers, in her view.

Of course, if you’re not happy with the major positions of either the Democratic or Republican parties in America, you are not going to be happy with a system that even further removes people from the process. But then your complaint is really with elections that assign winners via plurality vote, not with the particularities of party primaries.

That makes three reforms:

Compress the primary calendar

Use ranked-choice-voting (perhaps with multiple winners, called “STV” in the reform community) so eventual tallies better represent the balanced concerns of voters

Give party leaders a heavier hand in deciding who gets to run on their ticket. (You may avoid Trump by doing this.)

OK, that was a long answer. I’ll try to be faster with these next ones:

Seth D asks: “Given the GOP overperformance at the ballot box relative to polls in 2016 and 2020, how much should we round up on the Republican side when we see polling about 2022? are you spotting them a couple of points mentally?”

This is quite the hot question among pollsters and forecasters right now. In hazarding an answer we have to balance two concerns:

The first is that, when we look at the polls over the long-term, polling error has not been predictable from cycle to cycle. Democrats have tended to beat the polls in the cycle after they lag them, and vice-versa when they have beaten them. This means that when you train a model on the long-term history of the accuracy of polls to predict the next cycle’s error using the cycles before it, you essentially get a mean prediction of 0 with a wide confidence interval. In other words, historically speaking, no matter what the bias towards one party was last year, you should always predict a mean bias of 0 with a rather large standard deviation (around 3.5 points on margin for national polls) when predicting the next cycle’s bias.

“Ok, fine,” you may be thinking, “but patterns can change over time Elliott. What if polling error is more predictable today?”

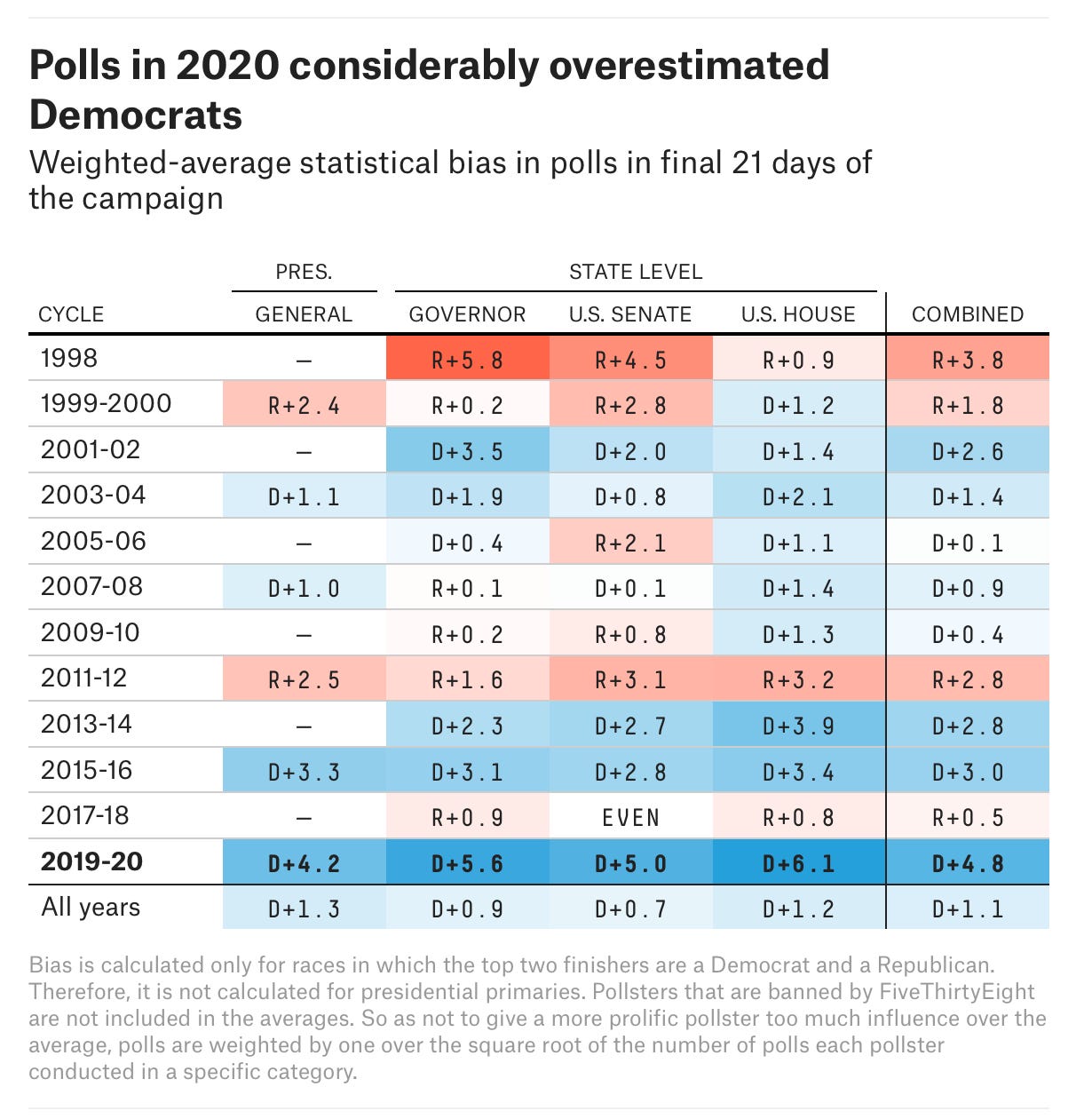

And that is the second concern! Take a look at this chart of polling error, cribbed from FiveThirtyEight’s analysis of polling after the 2020 election:

What may before have been a see-saw pattern is now a recognizably pro-Democratic one. And the only example of polls significantly underestimating Democrats (in the 2012 election) looks to have been a fluke. The polls even look to be getting significantly worse on average over time, with a bias of 4 points against Republicans in 2020, 3 points in 2016, and 1 point in 2008 and 2004.

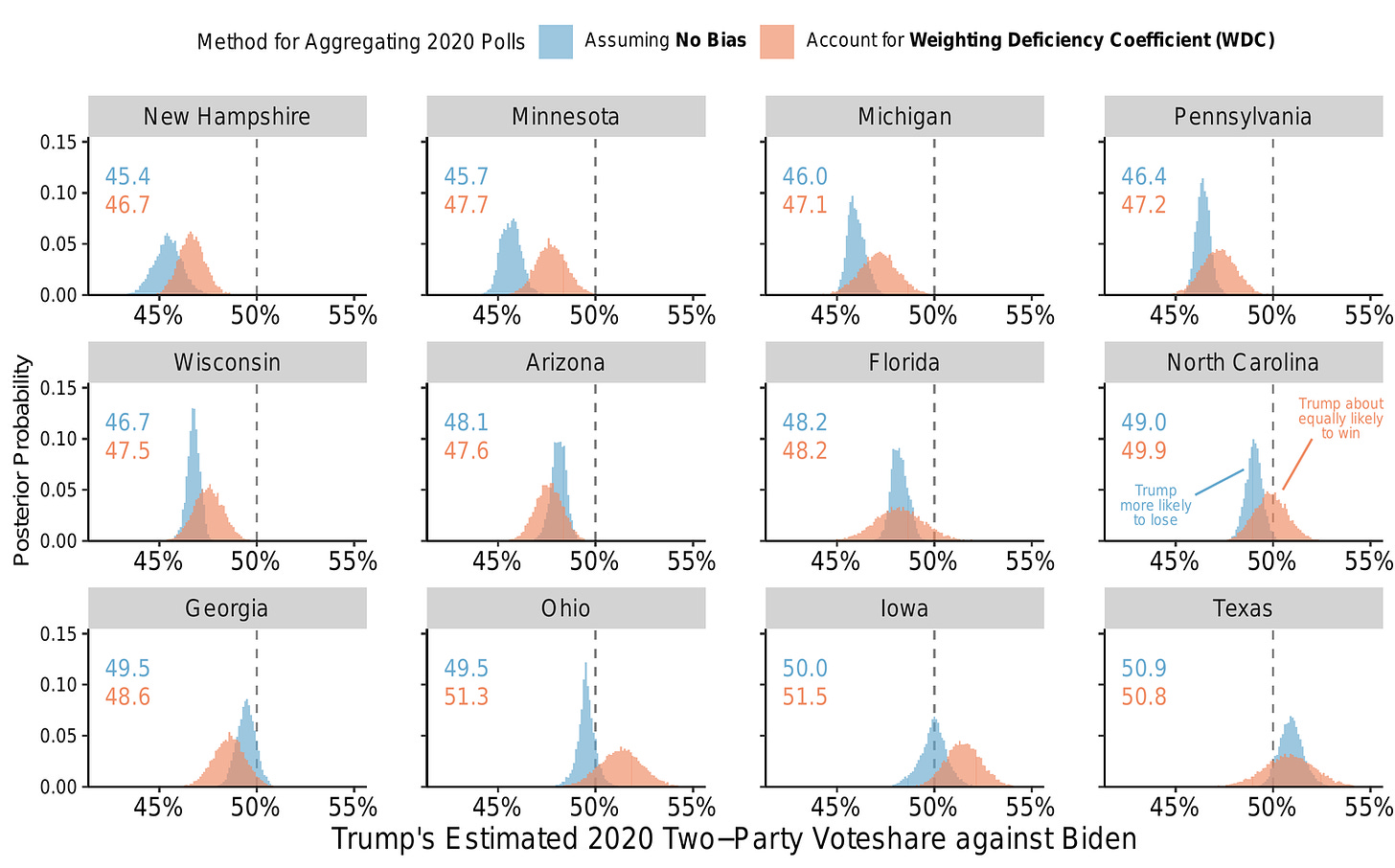

What this means is that our past predictions of polling bias (where the average guess should be zero in any forecasting model) may be meaningfully out of date now. I talk about this a bit in chapter 5 of my book but, in essence, the theories underpinning aggregation and forecasting from 2008 are empirically out of date now. Today, you get empirically better election forecasts by assuming the average bias of the polls in each state will be closer to the bias in that state in the last election than it will be to 0.

And that means, to answer Seth’s question, that if you want to play it safe, you should be subtracting a point or two off of the Democratic margin in the generic ballot polls when predicting what’s going to happen in the vote. But I should emphasize that these predictions come with a large band of uncertainty, too; there is still a chance that polls are biased toward Republicans today.

In a similar vein, Martha asks: “Would you care to elaborate on the relationship between polling and forecasting?”

There are two big differences. The first is that polls only tell us what people think about the election today; so when we’re further out from an election, we have to do more math to predict how those polls translate to public opinion on election day.

The second big difference is that polling is not the only data at our disposal when predicting elections. We also have historical data on how, say, the level of inflation predicts mid-term outcomes, or how presidential approval polls predict eventual votes. We tend to use these indicators to create so-called “fundamental” forecasts of election outcomes.

Bayesian applied statisticians, like me, tend to layer the polls on top of these predictions, meaning we use both to guide us: the “fundamentals” give us a rough idea of the path an election should take, and then the polls help us hone in on more up-to-date signals. But there is some debate over how much weight you should be putting on the polls versus the fundamentals (or both). Nate Silver, for example, says they are irrelevant come election day; my research at The Economist leads to a different, more nuanced view, saying you should lean on the fundamentals, particularly in very red and blue states, where we observe higher polling error.

Taj asks: “What are the best messaging frames that Democrats should use ahead of the midterm elections given that the topline issues are gas prices, housing affordability, and rising inflation (among others…)?”

Taj seems to ask this question with the starting point that eroding economic indicators mean Democrats are going to do poorly in the midterms. That seems right to me!

But it is important to note that midterm elections are fundamentally predictable based on a much simpler formula: the party in power almost always loses seats, usually about 28. This is because the overriding factor is a tendency to punish the incumbent party. That holds even if you control for things like GDP growth, change in real disposable income or the consumer price index, or a president’s approval. Barring a huge event (and, empirically, we mean a 9/11-style deviation from the status quo), Democrats are going to do poorly.

To me, this suggests Democrats shouldn’t be crafting their messaging frames around the midterms but their broader strategic policy and political goals. Conditioning on a bad midterm outcome, which I think has an 85-90%+ probability, what do Democrats want to accomplish? Then, test messages around moving the needle on those things.

That’s it for this week. Thanks to everyone who sent in a question and everyone else for reading. I am sorry if your submission was not answered. I will try to fit it into the next Q&A.

If you’d like to submit a question for the next edition, you can do that here!

In re electability - my experience with the Democratic Party was that there are several gates through which a candidate wannabe must pass. They are coming up through the ranks, electability based on previous performance, fundraising, skeletons in the closet, and Party scutwork. This is not new. Example: young person begins to attend Party functions, volunteers for scutwork like arranging chairs, showing up repeatedly, being available to drive people hither and yon, send out press releases. . . next comes law school or similar professional training. The person seeks local office with the backing of the county's Democratic party. And so on. The person must dress well, speak well, have a genuine interest in Democratic party policy and workings. . .