Political polarization (of policy preferences) is dramatically overestimated by partisans and the media | No. 170 — November 14, 2021

A new study from the Pew Research Center is a useful reminder that we contain multitudes

Politically, we have more in common than we think.

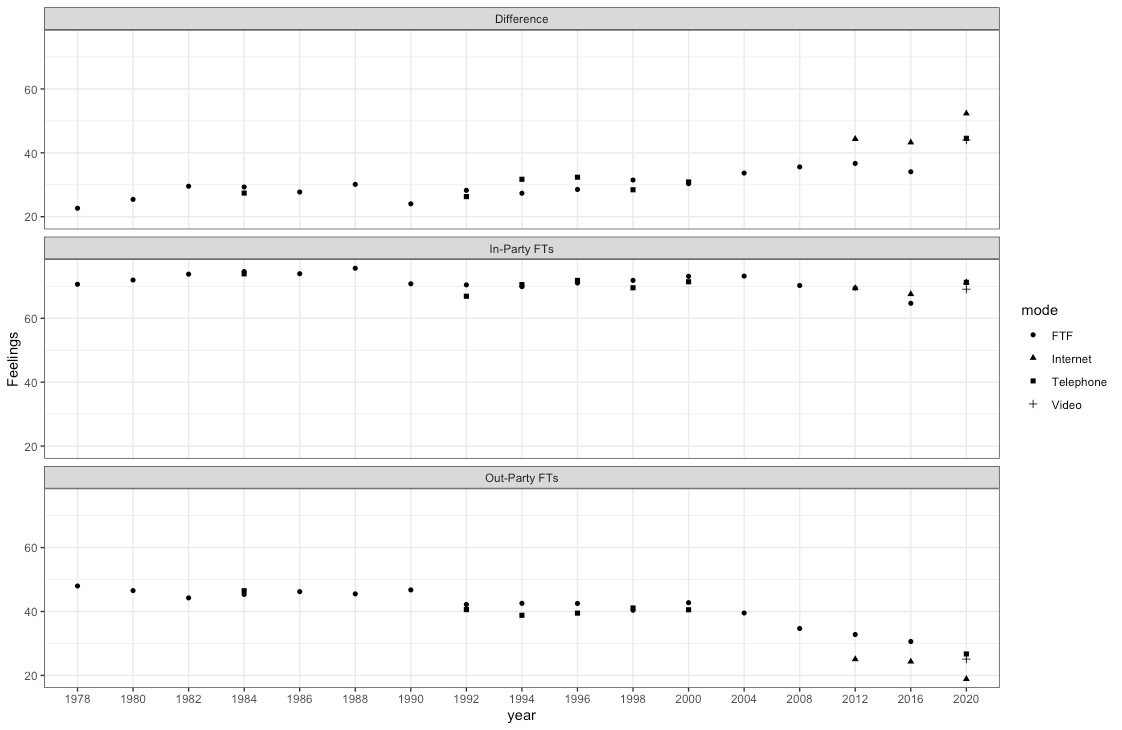

This is true on some levels and not true on others. For example, it is an empirical fact that Americans have grown further apart in their ideological, partisan, and otherwise political social identities over the last few decades. And here is a chart from friend of the blog Yphtach Lelkes that shows a marked increase in how “coldly'“ Americans rate members of their partisan opponents on a “feeling thermometer” scale ranging from 1-100. Negative partisanship is a hallmark trend of American politics over the last 20 years (and especially the last 10).

This increasing social distance has all sorts of negative consequences for the health of our democracy. It makes partisan elected officials less likely to cooperate with their opponents and the mass public more tolerant of violence and other bad stuff when it’s happening to members of the other party. It may even lead downstream to an increased likelihood that someone suspends their belief in democratic norms when their party is out of power.

And while I don’t want to downplay the seriousness of the increasing chasm between Democratic and Republican identities, it is simultaneously true that people overestimate the difference between the two parties on the policy preferences that they favor. A colleague of mine wrote on this subject early last month but I want to revisit it briefly with some updated data.

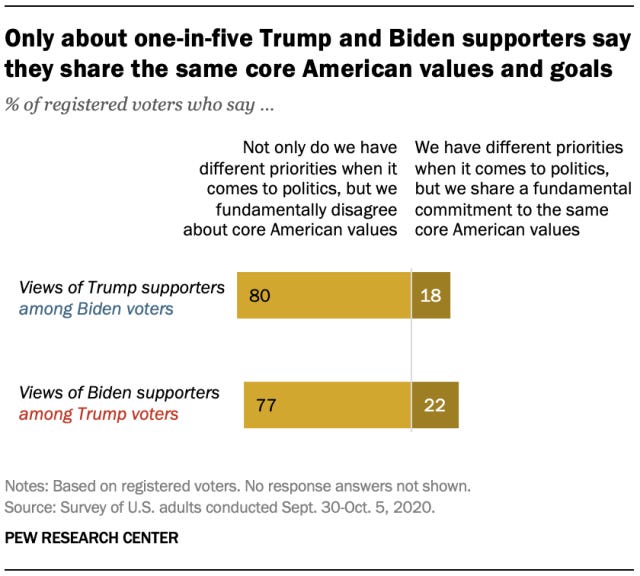

First, take a look at this chart. It comes from a report published by the Pew Research Center in October of 2020 that finds nearly 80% of both Biden and Trump voters said they not only had different political priorities than the other side but that they “fundamentally disagree[d] about core American values.”

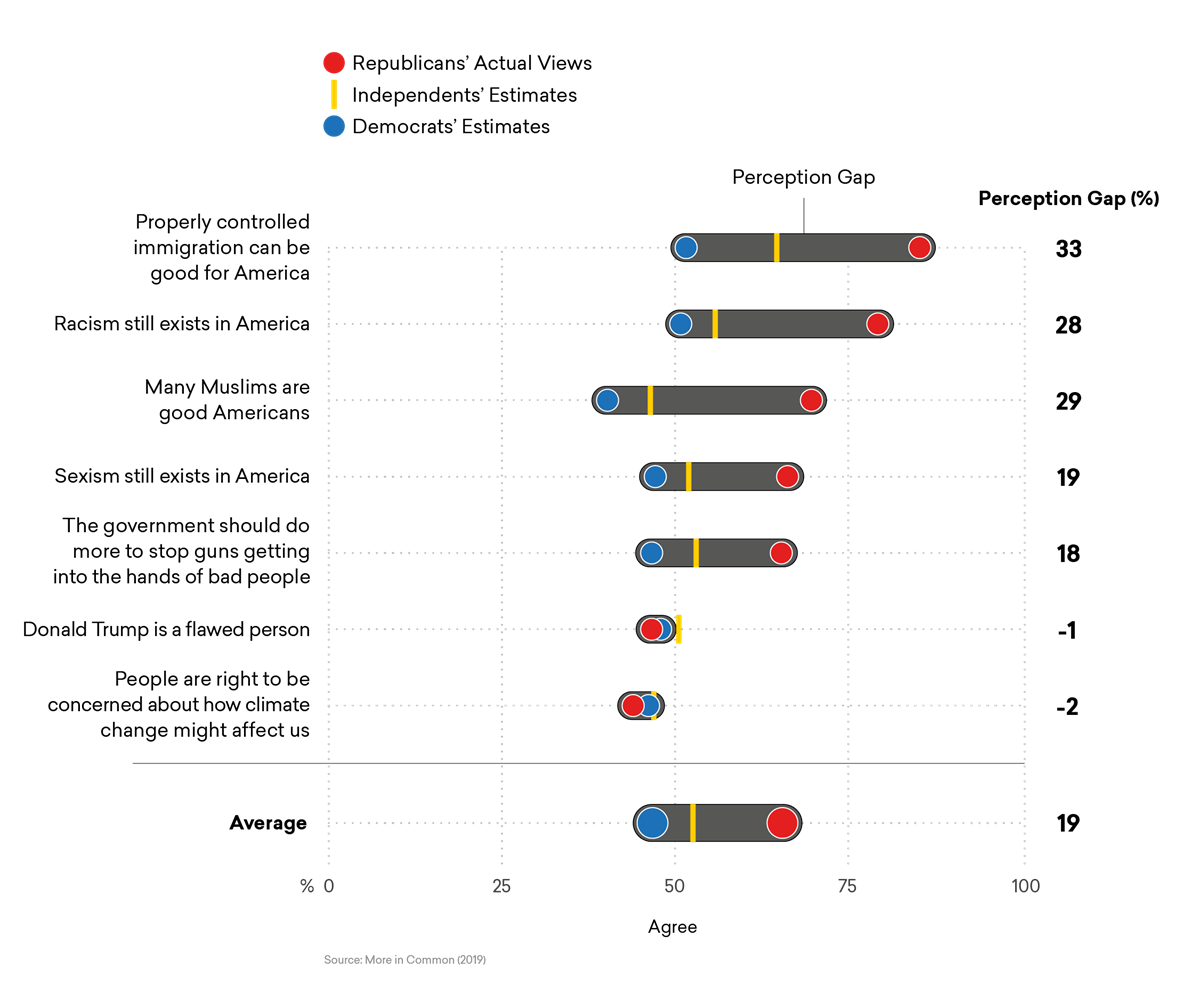

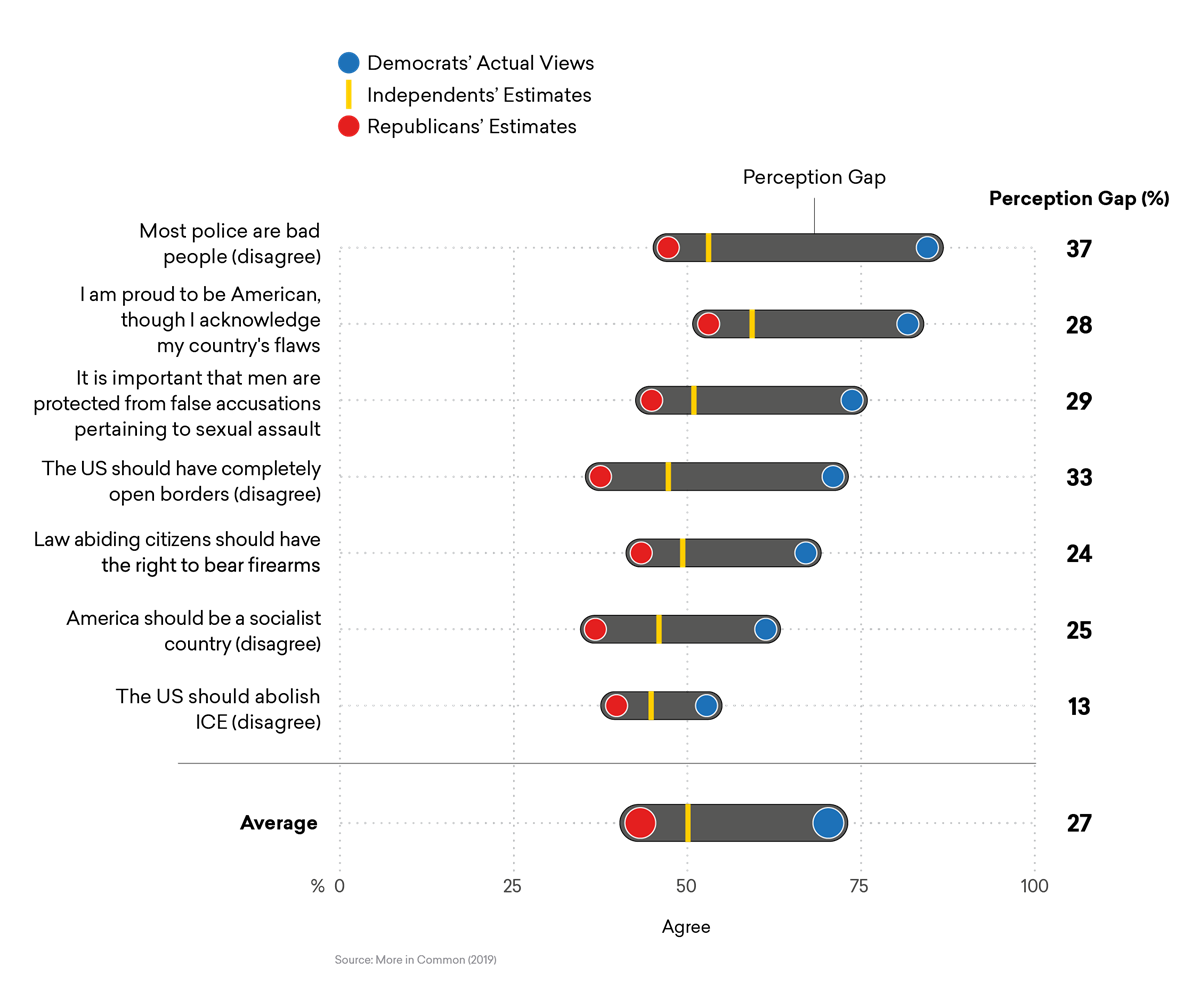

Further, the results of a quiz from the 2019 Hidden Tribes project show that Democrats tend to overestimate the conservatism of Republicans by about 20 percentage points on average, while Republicans overestimate the popularity of liberal opinions among Democrats by nearly 30. Here are two charts from their report:

The Hidden Tribes report also shows that the media, especially online and radio news programs, particularly (but not exclusively) on the right, are responsible for a good chunk of these misperceptions about polarization.

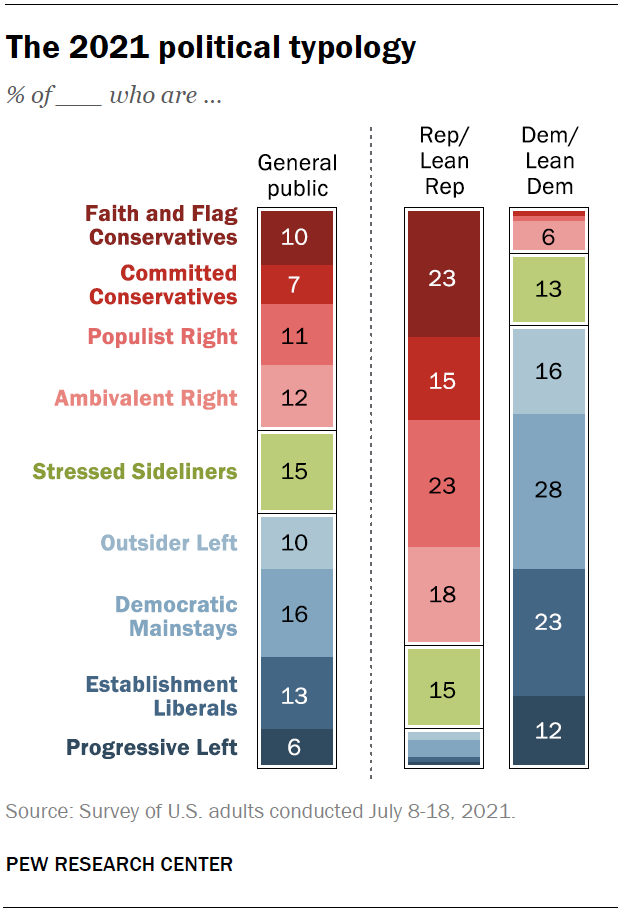

And that brings us to this week. The Pew Research Center published a massive report that sorts Americans into different “political typologies” depending on their responses to an array of questions (by the way, you can take a similar quiz yourself online here!). Pew finds there are roughly nine types of Americans, including four gradations of ideology in either party and one group of mostly non-partisan, disengaged Americans who don’t tend to participate in politics. These types are (from most progressive to most conservative):

Progressive Left (6%)

Establishment Liberals (13%)

Democratic Mainstays (16%)

Outsider Left (10%)

“Stressed Sideliners” (15%)

Ambivalent Right (12%)

Populist Right (11%)

Committed Conservatives (7%)

Faith and Flag Conservatives (10%)

Pew places Americans into these buckets based on survey responses to 27 questions on politics, religion, and society which then get run through a statistical algorithm called “cluster analysis” that optimally groups everyone into a set number of buckets — where each bucket is a group of voters who answer the most similarly across the questions. The algorithm is guided gently by researchers, Pew says, to make sure the groups it comes up with are meaningful.

That is a lot of statistical information that you don’t really need to know, but I do think it’s important to tell people that these categorizations are based on a computer’s categorization of 66 different responses to 27 questions by over 10,000 interviews Pew conducted in July of this year. So they aren’t (very) arbitrary — and yet Pew also happens to find that these buckets have strong partisan leanings to them, with very few “Faith and Flag” conservatives in the Democratic Party and not so many “Democratic Mainstays” in the GOP column, either. In fact, 79% of Democrats belong to one of the four major liberal groups, and 79% of Republicans are in one of the majority conservative groups, as seen here:

The other big points are (1) that the “Stressed Sideliners” are split roughly equally between the two parties; and (2) that the most extreme conservative grouping makes up a much larger chunk of GOP voters (23%) than the most progressive Democratic grouping (12%). This asymmetry in ideological polarization is also important for lots of downstream reasons that I have addressed in this newspaper, including the most obvious point that Democrats have to compromise more than Republicans do on policy positions and prioritizations in order to satisfy all of the members of their “big tent” coalition.

OK, but wait, this newsletter was about how we have more in common than people think, right? Yep. All this focus on red and blue buckets kind of distracts from that point, but it’s important that you get the lay of the land. But Pew’s new political typology study shows, first and foremost, that the average Democrat and Republican are not the ideologically extreme partisan the other side thinks they are. The biggest group in either party are the (relative) moderates: the “Democratic Mainstays” and “Outsider Left” (for the Democrats) and “Populist Right” and “Ambivalent Right” (for the Republicans). A very small number of Americans are Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez Democratic socialists or Marjorie Taylor Greene far-right populists. (NB: I am not picking these two Congresswomen because I think they are equally extreme or similarly valenced in their devotion to Liberal Values or some such, but because they are both well known and the farthest apart members of the House, according to the political scientists who run VoteView.com)

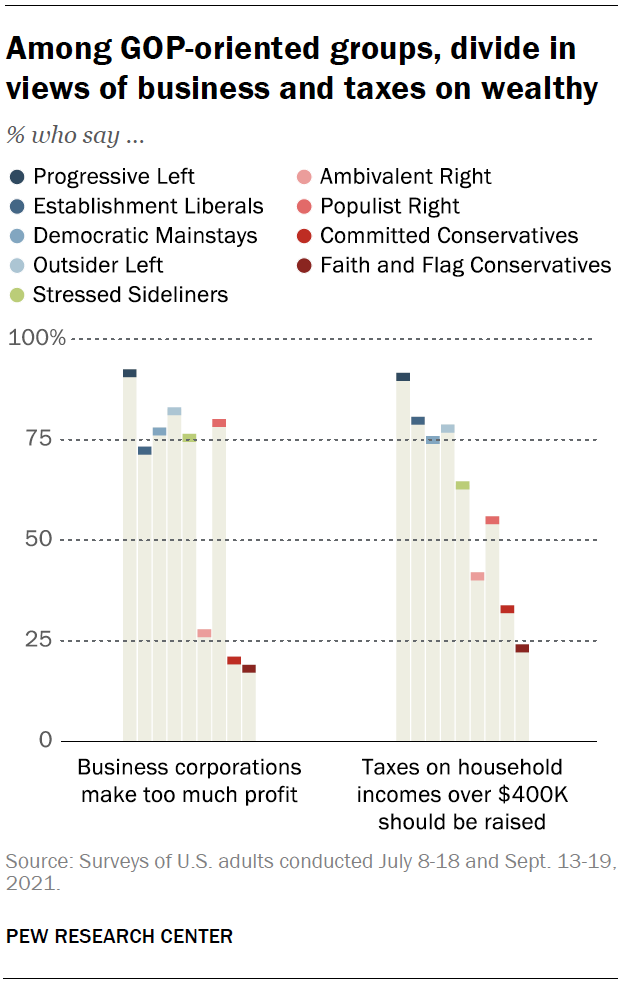

Yet when you look further under the hood, the Pews study also finds a lot more bipartisan agreement on, eg, economic policy than a naive glance at the groupings suggests. Over 75% of people in the “Populist Right” bucket, for example, think that corporations make too much profit — roughly the average for all of the left-leaning groups — and about 60% of them think the government should raise taxes on households earning more than $400k annually.

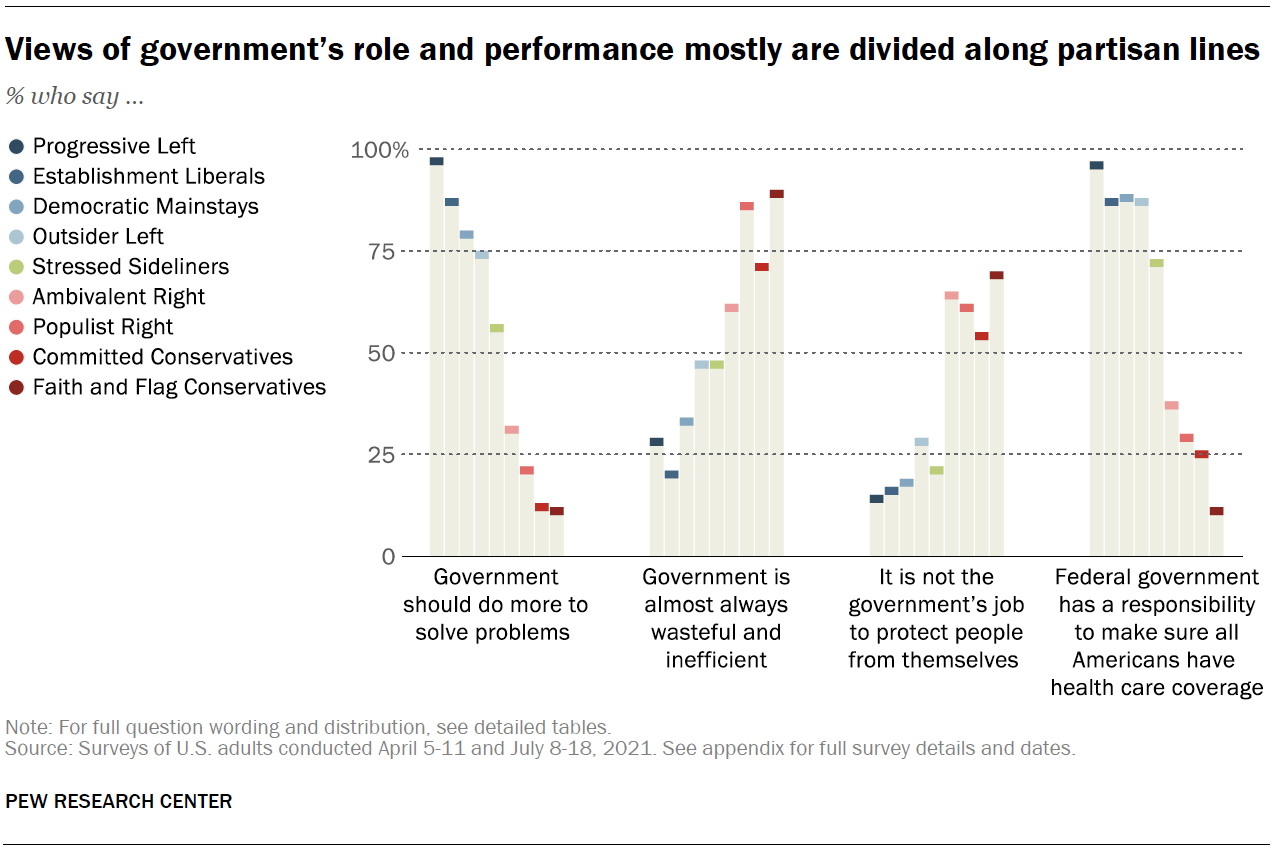

And even on more divisive issues, there is still a good amount of overlap, with roughly one-fourth of voters in the partisan buckets agreeing with the positions we’d associate with the other side (there are even more images like this in the report):

And then in this graph, you can see that the most moderate liberal group (the “Democratic Mainstays”) are about as close to the most liberal group as they are to the most moderate conservatives (the “Ambivalent Right”).

I could go on. Here is another chart showing a good bit of ideological overlap between Democrats and Republicans, from a new paper by political scientist Alan Abramowitz:

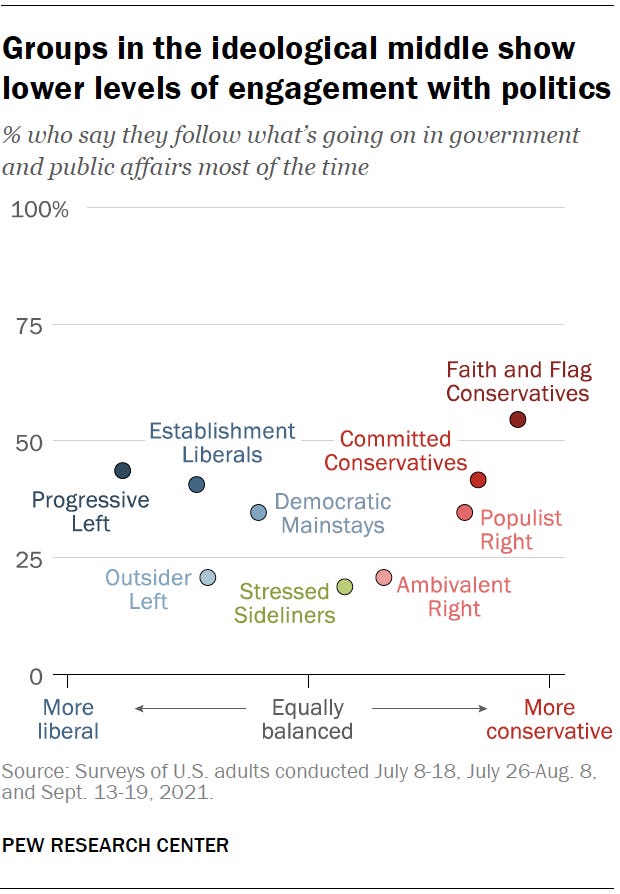

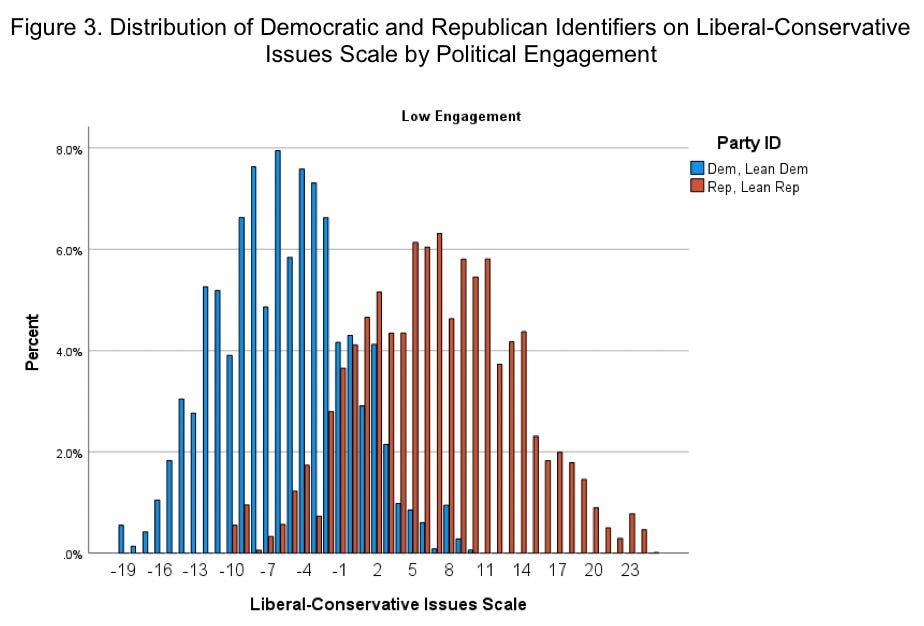

And lastly, on that note, I think it is important for us people who study or write about politics for a living to acknowledge that people who don’t pay much attention to the news are even closer ideologically:

. . .

This is all just an empirical way of proving that first sentence. This is important for people to realize for at least a few reasons. First, it’s the reality of American ideology and political psychology today, and we ought to be devoted to discussing factual matters instead of myths. But recognizing that we share a good amount of our political ideology even with our neighbors who wear the colors of a different political tribe is also an important step to healing some of the damage caused by our profound divides in identity and affect. Building better parties (and, with luck, political systems) will also come only after we can build a better consensus, and to do that we must start seeing the other side not as the worst versions of their co-partisans but as citizens with an equal voice in the democratic process and a lot more in common than we usually think.

Posts for subscribers

If you liked this post, please share it — and consider a paid subscription to read additional in-depth posts from me. Subscribers received one extra exclusive post over the last week:

Links to what I’m reading and writing

This weekend I have been re-reading Walt Whitman’s Democratic Vistas, which was one of the texts that inspired me to write a book both on polling and democracy, rather than just focusing on the art and science of surveying in the 21st century. At least in my surface-level understanding of, and amateur opinion on, poetry, Whitman is unmatched in his devotion to developing the (American) democratic spirit. And in line with the main column today, I think it would all do us some good to read not just Whitman the poet, but Whitman the political theorist.

Last week at work, I did a lot of data wrangling and preparation for a few articles that will go up this week (before I go on vacation for the Thanksgiving holiday), and I wrote a response to a column on Hispanic voters and the Democratic Party than ran in our weekly edition. I’ll have an article up tomorrow on how inflation is affecting Americans’ day-to-day lives and one later this week on whether stimulus funding helps Democrats. (No spoilers!)

Finally, a shout-out: I have been finding the FiveThirtyEight Congressional redistricting tracker an invaluable resource for all things gerrymandering and map-making, and I think it has improved the public conversation about these things. They do a good job of running a variety of statistical tests on maps to detect various levels of bias and prevent changes in a pretty concise way. It reminds me a lot of the Planscore site, which is a bit more technical but also extremely valuable in providing plan scores over time. Props to both groups!

Thanks for reading

That’s it for this week. Thanks so much for reading. If you have any feedback, you can reach me at this address (or respond directly to this email if you’re reading in your inbox). I love to talk with readers and am very responsive to your messages.

My own lens is that people are being driven apart by television station propaganda. Americans get our information from social media and television. Deplorable. Americans have no interest in exercising our critical thinking skills. Contemptible. Americans nod our heads at what TV pundits say. Rubes. TV pundits and social media advertisers don't have to work very hard to get people to believe their propaganda. Canada doesn't allow outfits like Fox to operate as News. If GOPTV is ever required , blackmailed, or definanced into reducing its propaganda, we will see that less propaganda brings those of us under the bell curve closer together.