The 2022 US House maps are set to be the least competitive in a century

Political science says a lack of competition will decrease accountability, sow polarization and hasten democratic decline

Reid Epstein and Nick Corasaniti reported for the New York Times this weekend that politicians are “Taking the Voters Out of the Equation” when drawing this decade’s new boundaries for Congressional maps. As a refresher, the US government takes a new nationwide Census every ten years, and states must redraw their maps to have equal shares of the population within states and meet various other criteria for compactness, contiguousness, racial representation, and (in some states) partisan balance.

Epstein and Corasaniti write:

In the 29 states where maps have been completed and not thrown out by courts, there are just 22 districts that either Mr. Biden or Mr. Trump won by five percentage points or less, according to data from the Brennan Center for Justice, a research institute.

By this point in the 2012 redistricting cycle, there were 44 districts defined as competitive based on the previous presidential election results. In the 1992 election, the margin between Bill Clinton and George H.W. Bush was within five points in 108 congressional districts.

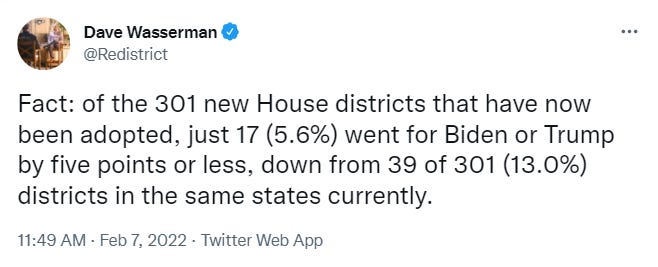

Interestingly, Dave Wasserman of the Cook Political Report writes that the number of competitive seats is even lower, pegging it at 17 instead of 22:

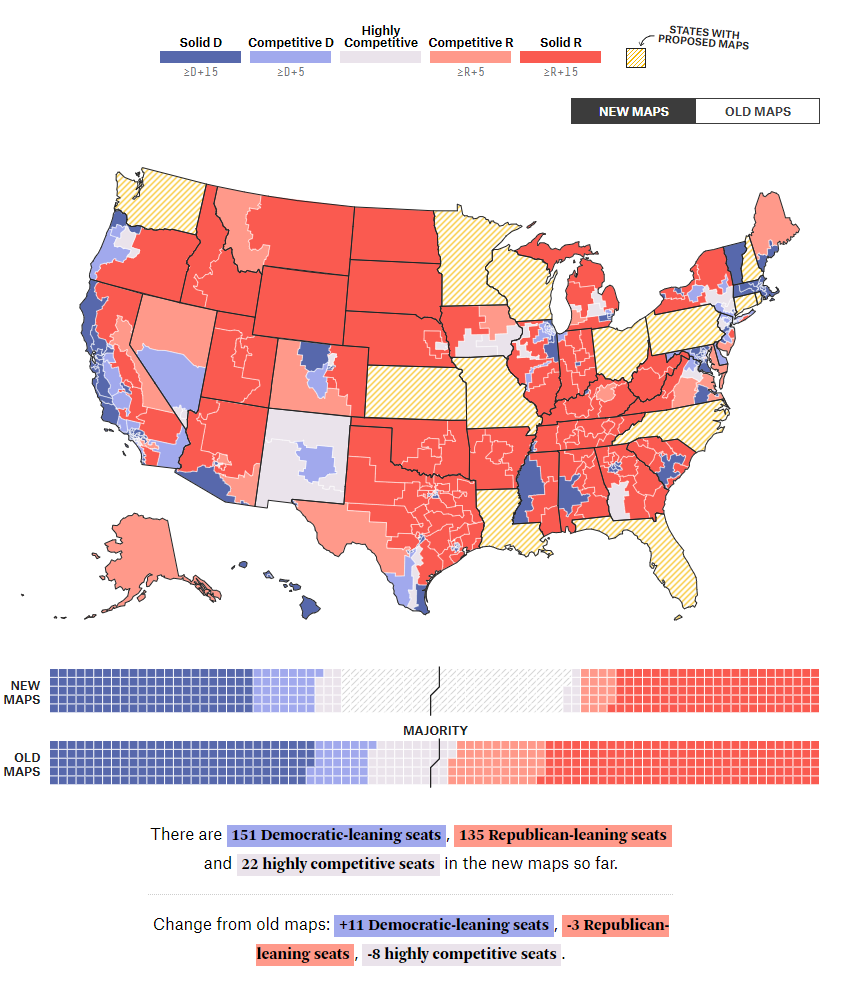

I’m not totally sure why they are disagreeing (Wasserman doesn’t say anything except the NYT has some sort of error in their data). But I have been able to replicate the 22 number — but only if I use the partisan lean (or “partisan voter index” (PVI), per Cook’s naming) of each district. I get that data from FiveThirtyEight, which has done an excellent job tracking redistricting as states draft, submit, and finalize their new boundaries. This is a screenshot of their excellent interactive:

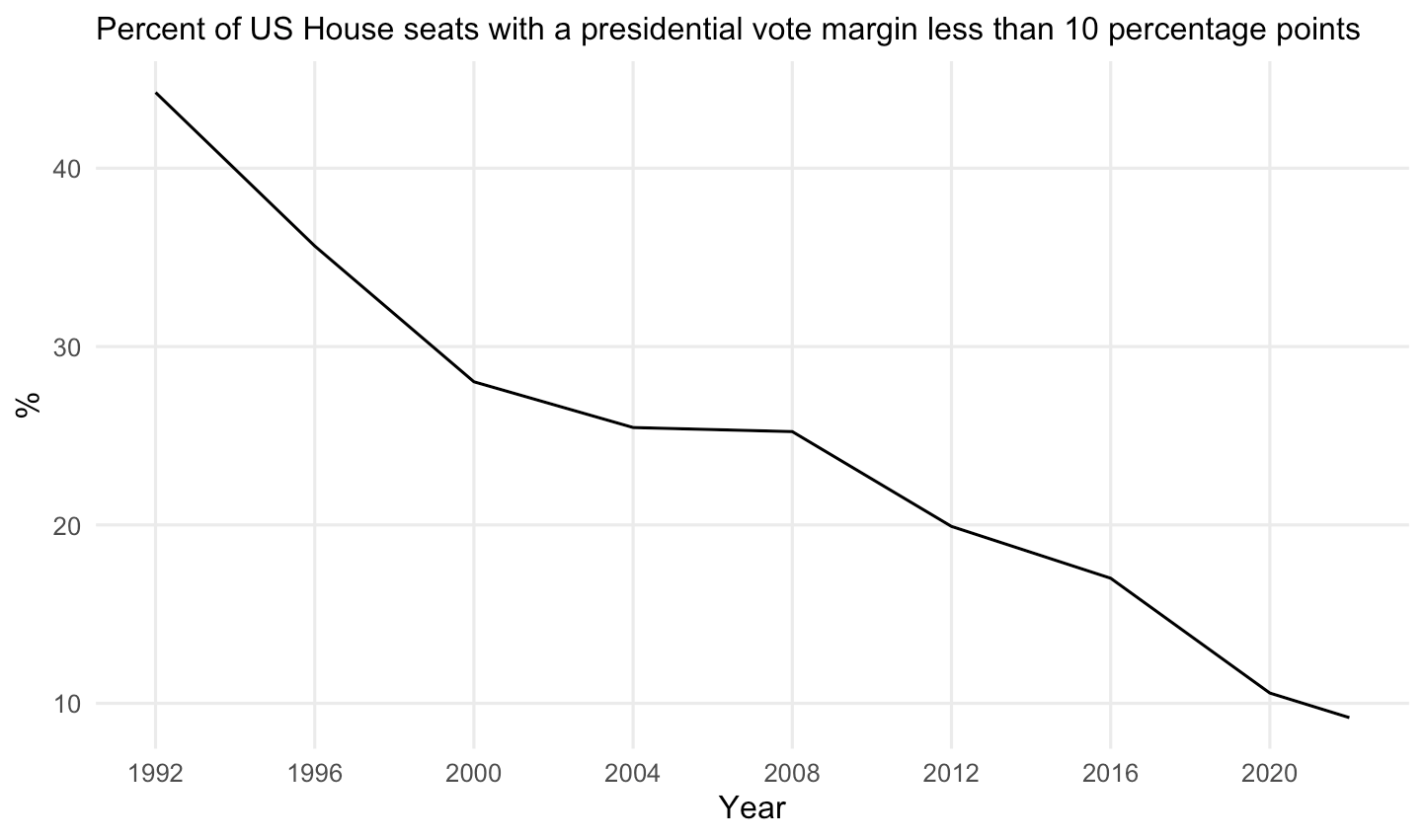

Anyway, they also make the underlying data for their interactive available for public consumption, which is awesome. I am able to download their data and see how many competitive seats there are for myself — again, based on their estimates of PVI in each district. Now, I want to first expand the definition of “competitive” as a race that leans less than ten points towards Democrats or Republicans in a completely neutral year. Dave and 538 typically use five, but I think ten gives us a better representation of seats that would be competitive if incumbents didn’t have advantages or fundraising was equal. Ten just captures the potential distribution of competition a little better, I think. (NB: this doesn’t actually matter. The story is the same with a 5- or 10-point threshold).

So if I count up the number of competitive seats per year, then divide by the total number of seats in the house of representatives, I get a plot that looks like this:

And, lastly for the data, the latest release of Vital Statistics on the US Congress from the Brookings Institution shows that the last time the number of congressional districts carried by a presidential candidate of one party and a House candidate of another party was this low was in 1920 — a century ago.

After all the states submit their final Congressional maps for 2022-2030, political competition will likely measure at a 100-year low.

This is all pretty devastating — at least if you believe competition is good for democracy. This prompts me to highlight how these institutional issues are negatively impacting our politics today.

. . .

In the wake of the January 6th attack last year, the Washington Post and ABC News published a poll that found “overwhelming opposition” to the riot and support for prosecuting rioters. Quoting from their article now:

Overall, almost 9 in 10 Americans oppose the storming of the Capitol, including 8 in 10 who say they strongly oppose the attack, which resulted in the deaths of one police officer and four rioters, left dozens injured and shook the country. On this question, 98 percent of Democrats, 80 percent of Republicans, 89 percent of independents, 87 percent of White Americans, 94 percent of Black Americans and 93 percent of Hispanic Americans agree in their opposition to the violent insurrection.

And they go on, detailing how the attack decreased confidence in US democratic institutions:

The events of the week of the attacks have resulted in people saying they are less confident in the stability of democracy in the United States, with 51 percent saying that is now their view, compared with 13 percent who say it has left them more confident and 32 percent saying the attacks and related events have made no difference in their assessment.

One respondent they conducted a follow-up qualitative interview with said it was “kind of frightening that people would feel a sense of anger that would prompt them to do something like that…. the president of the United States outside the White House asking people to march on the Capitol, to disrupt what the U.S. Congress was doing.”

And then, over the last two weeks, you have two concerning events: First, Donald Trump promising to pardon people convicted for attacking the Capitol last January; and, second, the Republican National Committee issuing a statement calling the assault “legitimate political discourse” and censuring the two GOP representatives participating in the House Jan 6. Inquiry.

WHEREAS, Representatives Cheney and Kinzinger are participating ina Democrat-led persecution of ordinary citizens engaged in legitimate political discourse , and they are both utilizing their past professed political affiliation to mask Democrat abuse of prosecutorial power for partisan purposes, therefore, be it

RESOLVED, That the Republican National Committee hereby formally censures Representatives Liz Cheney of Wyoming and Adam Kinzinger ofIllinois and shall immediately cease any and all support of them as members ofthe Republican Party for their behavior which has been destructive to the institution ofthe U.S. House ofRepresentatives , the Republican Party and our republic, and is inconsistent with the position of the Conference.

That ought to be normatively concerning to us. Partisan violence is a red line liberal democracies are not supposed to cross. And yet, most Republican voters approve of the president and disapprove of Reps. Cheney and Kinzinger.

Which brings us to a circular question: What should we expect Republican elected officials to do in this moment? An easy answer is “the right thing.” Ok, obviously in a world with perfectly rational actors and sound leadership nobody should support violence and attempted overthrows of elections in America. But we don’t live in a world with rational politics. We live in a world with increasingly hardened partisanship, especially on the right. Support for democracy itself has even become somewhat of a partisan issue. Here are some polling data from Bright Line Watch, collected just after the January 6 riot:

And, (to bring this back to the data!) we also live in a world where more and more elected officials are not subject to significant general-election competition at the ballot box. The lack of competition we observe at the top of the piece insulates politicians from rational accountability. That means they have more room to act in ways that are contrary to the expansion of liberal democracy in the US.

And it also means, sadly, that we should expect more norm-breaking and democratic decline in US politics in the near future. Without incentives toward moderation, or doing the right thing, fewer and fewer Republican politicians are going to stand up for things like the legitimacy of elections regardless of results, voting rights, equal access to participation, and fairness in representation in Congress and state legislatures — among other values.

. . .

Uncompetitive House elections are yet another aspect of our politics that are produced by America’s peculiar and dramatically inadequate electoral rules and institutions — peculiar because few other countries elect legislators via plurality votes single-member districts, and inadequate because of their inefficiency in translating citizens’ attitudes to inputs into the democratic process.

It is worth remembering that democracy requires that the signals from voters are properly processed. Our institutions are currently scattering those signals, and are a good target for reform. Various proposals for proportional representation are a good place to start.

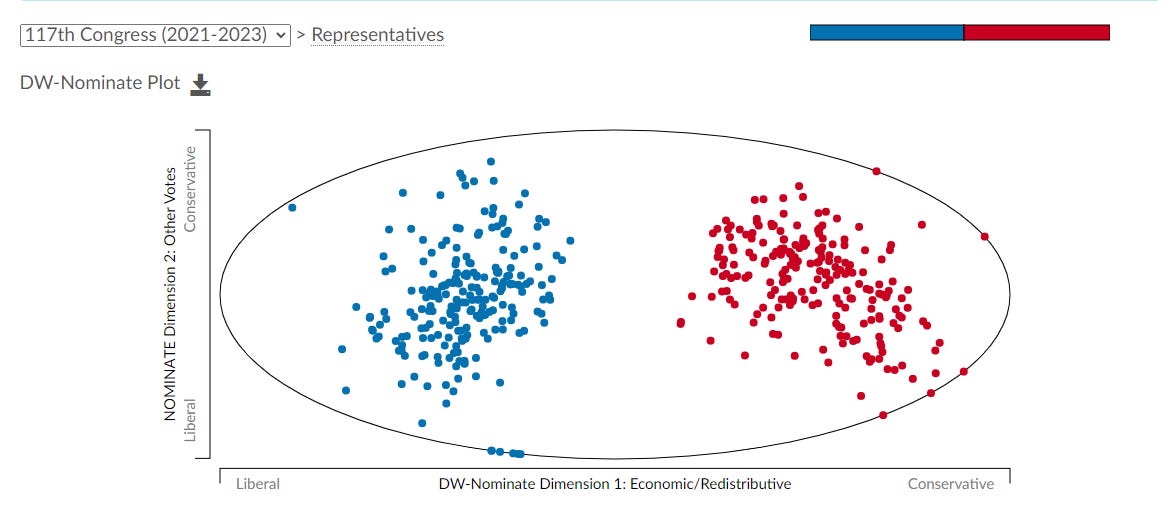

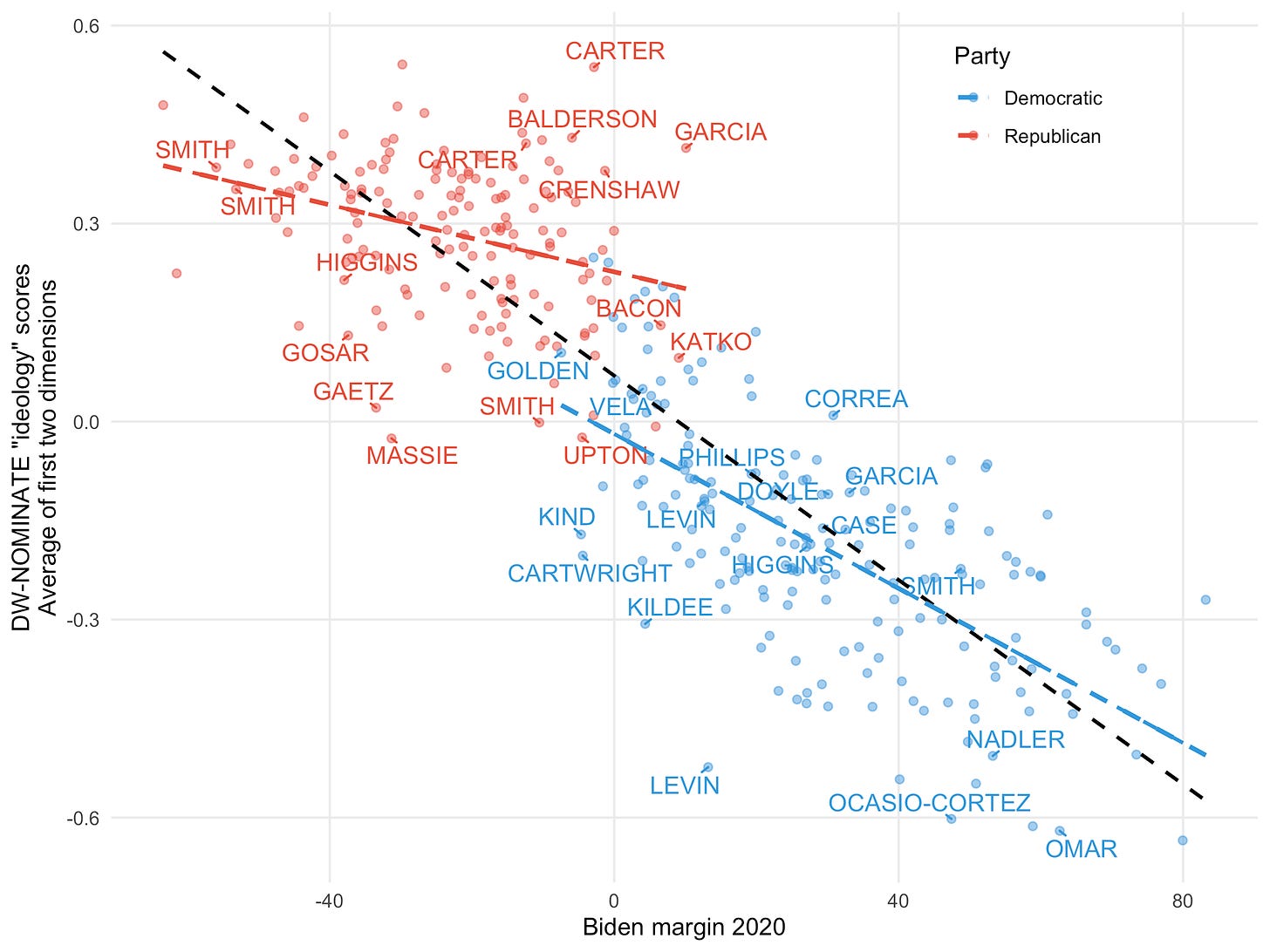

Still, I should add the caveat that competition is not everything. Though a lack of competition is correlated with polarization, and we know voters tend to reward moderates, it is not the sole cause of polarization, gridlock, groupthink, or what-have-you. We know this because voters and politicians are dramatically more polarized across parties than between them. A scoring system for the ideological lean of each US House representative shows a chasm between the parties…

… and a somewhat loose correlation between their ideology and the partisanship of the district they represent, within parties:

This is just to say that electoral competition is not a silver bullet. There are still other causes of polarization in our politics that will not be solved with, eg, multi-member districts and ranked-choice voting. Polarizing opinion leadership from rogue elites and cable new commentators is one of them. A partisan divide over civil rights and multiethnic democracy is another. And embedded tribal affiliations among groups with very strong social attachments, and little in common with the other group, are not just going to vanish.

Low competition is, however, one variable that we know how to fix. And the hope is that getting the snowball rolling on depolarization would affect positive changes downstream.

Great stuff visualizing the trend. Becoming clear what incentives are built into the fabric of American institutions