Links for January 22-28, 2023 | The research on achieving racial justice; The debt ceiling debate; and Who cares about the House Speaker, anyway?

69% of adults think the US defaulting on its debt would be a major problem

This is my regular weekly roundup of articles/books/charts etc. I’ve read or media I’ve watched that I think are interesting and worth discussing. This week, I’m thinking about public opinion on racial justice and sharing a few other links I found insightful.

1. Researchers don’t really know the “right” way to protest

On January 7th, five Black police officers from the Memphis Police Department pulled over 29-year-old Tyre Nichols, a Black man, allegedly for a traffic violation, and beat him so brutally he had to be hospitalized. He died three days later. Last week, Memphis PD released the body-cam footage of the traffic stop and subsequent beating of Nichols. There have been nightly protests against police brutality across the country since. On Friday the police announced the officers had been fired and arrested for allegedly murdering Nichols.

This is an all-too-familiar story. There is little I can say that has not already been said about the alleged murder, the racist systems that make police slayings of unarmed Black men commonplace or the many failures of the police in this and other situations. But on the subject of how Americans can achieve justice for Nichols, and racial justice more broadly, I have a few notes.

After the murder of George Floyd in 2020, a conversation (among mostly very-online people) emerged about what the best strategy is for people to affect change on race and civil rights. A line was drawn between violent and non-violent protests. One side said violence (to people, property etc) is unnecessary and detracts from the cause. The other justified hostility towards police and the burning and looting of buildings by saying they get peoples’ attention. The former opinion is notable as a long-standing (lower-case-“c”) conservative talking point whenever protests and riots break.

There is some social science on this question. Some readers may remember online controversy in 2020 over a study by Omar Wasow, a political scientist, who looked at violent and peaceful protests in the 1960s and found that violence increased vote share for Republican presidential candidates by up to 8 points, costing Democrats the 1968 election between Richard Nixon and Hubert Humphrey (and George Wallace). Wasow’s study relied on county-level rainfall data to approximate where “protest-induced” violence occurred in 1968.

It is interesting, then, that a very similar study of the protests following the murder of George Floyd in 2020 found the exact opposite effects. Two economists again used data on rainfall to assign levels of protest in each county in the US. They then analyzed whether counties that experienced more “protesting activity” (rainfall) shifted left or right in the November election, after controlling for other potential factors (like certain demographic and political variables). The paper finds the 2020 BLM protests caused a roughly 2-point boost for Joe Biden’s vote share in the county with the average level of protest. They also look at survey data and find that peoples’ attitudes changed markedly over the year, becoming more “liberal” on a variety of measures.

That these similar studies of similar phenomena come to different conclusions ought to teach us a lesson about using social science for policy prescriptions. In 2020 it was evidently tempting for a lot of very online, data-familiar types to argue that violent protest is harmful and that Black Americans should instead express themselves in more palatable ways, such that public support for the movement would increase. But there is little empirical evidence to support such a view. Since the tragic and savage killing of Tyre Nichols, I have seen little interest online in restarting this debate. That is for the better.

2. Most Americans want Congress to raise the debt ceiling

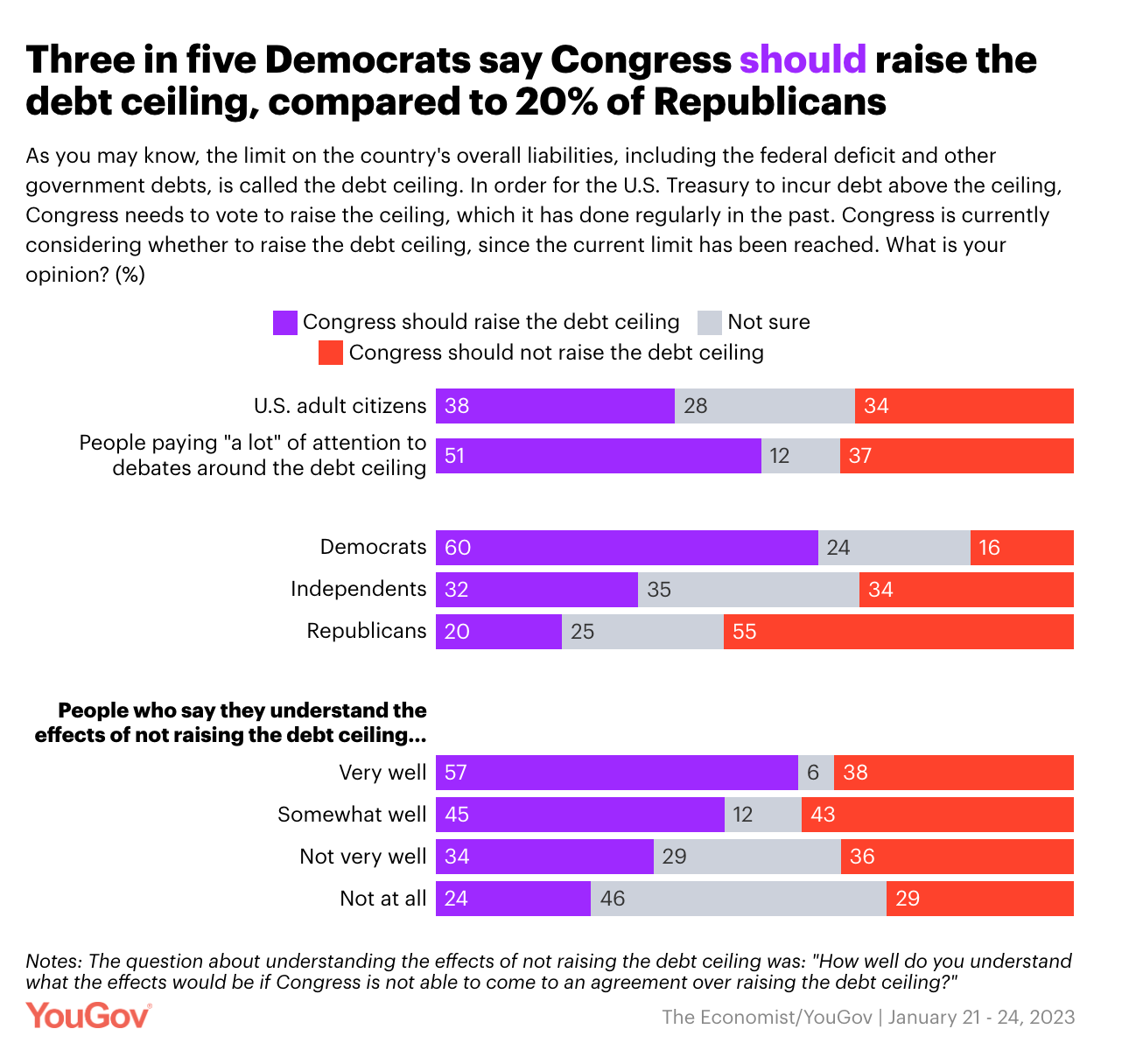

A new poll from YouGov and The Economist released last week found plurality support for Congress raising the debt ceiling. But not many Americans even know what the debt ceiling is. A handy feature of the poll is that it’s big enough for YouGov to ask people if they understand the consequences of not raising it; among people who say they understand those consequences “very well,” 57% say raise the limit v 38% who are opposed. Most of the opposed are Republicans. More results here:

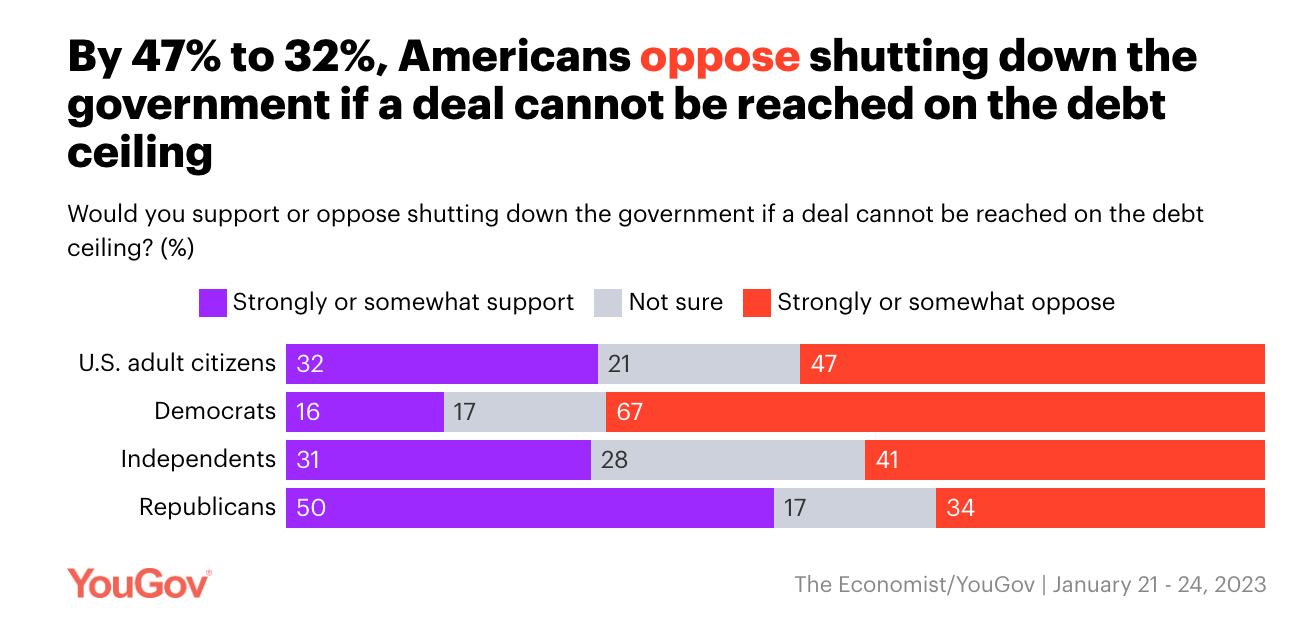

And when respondents were explicitly told the consequences of not raising the debt ceiling (the government shutting down) most were opposed to letting the country careen over its fiscal cliff:

Here is one of those issues where it’s important to remind ourselves that most Americans know nothing about this issue at all. Only 18% told YouGov that they understood it “very well,” and that may be an inflated number due to the inherent biases of political polls toward respondents with higher political engagement. That ties in perfectly with our last link:

3. “Republicans Didn’t Get Less Popular After All That Speaker Drama — They Were Already Unpopular”

Such is the title of a FiveThirtyEight article which begins:

The election for speaker of the House may have gripped Washington, D.C., for almost a week earlier this month, but the rest of the country apparently reacted with a big fat shrug.

And for the data:

Two polls found that a plurality of Americans thought that the drama surrounding the speaker election hurt the GOP. According to a HarrisX/Deseret News poll conducted right after McCarthy’s election, 41 percent of registered voters felt that the Republican Party was weaker after the speaker election, and only 23 percent thought it was stronger. In addition, 43 percent of registered voters told HarrisX/the Deseret News that the ordeal made them trust the Republican Party less. Meanwhile, 34 percent of respondents told Ipsos that the drama weakened the Republican Party, and only 19 percent said it strengthened the party.

But the author, Nathaniel Rakich, is quick to note that these poll questions don’t mean much. They are asking a very engaged set of Americans to opine on an ongoing event, speculating about changes in attitudes that will happen sometime in the future. What if we just waited a few weeks and looked at the tracking polls?

Lo and behold, there has been no change in the public’s view of the Republican Party since the Speaker drama earlier this month. The GOP’s unfavorability rating according to Civiqs, an online polling firm, is 63% today — one point lower and within the margin of error of the firm’s estimate for January 1st, 2023. Over the same period, there has also been no change in the public’s view of the Democratic Party or how people respond to the question “Which party is more concerned with people like you?”. See here:

This is a great reminder that pontificating about how the public will react to an event is usually a foolish endeavor. Perhaps because pundits are over-socialized with people who pay attention to these things, or maybe just because they’re incentivized to have over-confident opinions on everything in the news, they tend to dramatically overestimate how much the average American responds to external stimuli.

Most people, for better or worse, aren’t paying attention to what’s happening in Washington at all.

That’s it for this weekly edition of my top links. Thanks for reading and being part of the community that supports this newsletter.

Elliott

I'd need to see definitions of "violent" before any of the rest makes sense.