Links for February 26-March 4, 2023 | Predicting primaries; "Wokeism" and depression?; And new evidence of voter rationality

How to look at lines that go up

Happy Saturday, all

This is my weekly post for paid subscribers discussing recent uses of (mostly political) data that I think are interesting and worth discussing. Comments are welcome below — and if you enjoy this, please share it with a friend!

1. Is past really precedent for the 2024 Republican Primary?

Harry Enten at CNN had a bold piece up Saturday: “Why Trump is a clear favorite for the 2024 GOP nomination.” According to his number-crunching, Trump has the support of 44% of Republican primary voters, on average, versus 29% for Ron DeSantis, his most formidable opponent.

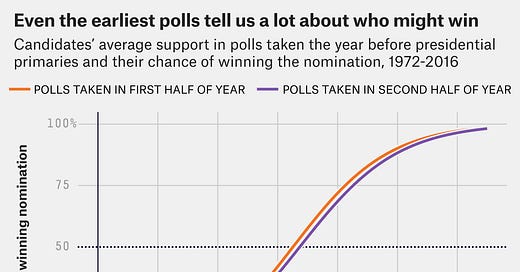

Enten cites a 2019 article from FiveThirtyEight that finds primary candidates with 45% in the polls have gone on to win the nomination more than 75% of the time. That puts Trump ahead of the field—DeSantis, by contrast, would have just under even odds to win. Previous candidates with Trump-level support who have won the nomination include Gerald Ford, George HW Bush, and Bob Dole.

Trump also drew a larger crowd than his challengers at this weekend’s annual Conservative Political Action Conference, though even his was nothing to write home about.

My take? First, a 25% chance is higher than it seems, especially when we consider the sample size for these models is very small. We have a dataset of 16 competitive presidential primaries since the 1969 McGovern–Fraser Commission, and the vast majority of the polls for these contests have come since the year 2000.

But second, there could be a lot of factors influencing nominations that our (necessarily) simple models cannot account for. Maybe polls are more predictive when an incumbent is running; maybe early leads are less predictive when there are only two or three competitive candidates. And most of Trump’s likely challengers, such as DeSantis and former vice president Mike Pence, haven’t even announced yet. I could go on.

This early, with what looks like a very volatile election ahead, I’m not prepared to say that any one candidate is favored to win the nomination. Betting markets give Trump a much smaller probabilistic lead than the above analysis of the polls does.

2. Does this graph that “wokeism” is causing depression?

There was a bit of pundit discourse last week about what, exactly, is causing elevated levels of depression among young people. One theory popular among very online people, especially those on the left, is that a grim future for the climate, social services, and society more broadly—the collective consequences “Late State Capitalism,” as it’s often called among the Youths—is inherently depressing for young generations. Another theory is that it’s our phones.

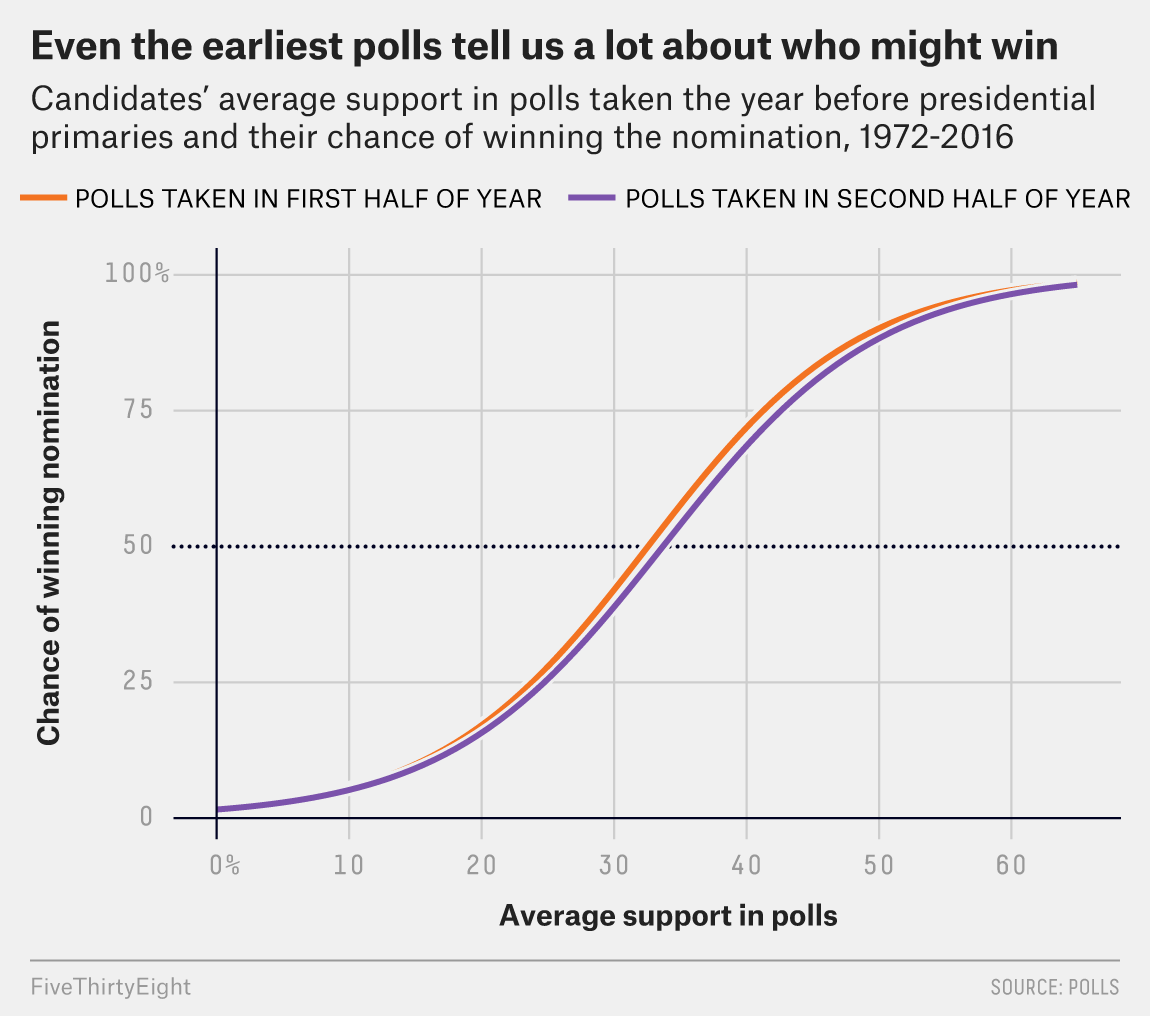

Matt Yglesias, the popular pundit, has another theory. “It’s not just young women whose depression rates have surged,” he claimed on Twitter last week, “it’s specifically young liberals, with liberal teen boys actually faring worse than conservative teen girls.”

As proof, he analyses the following graph in a piece published on Substack last Wednesday:

Setting the remaining substance of the article aside, I think the above graph is particularly bad evidence for this thesis. If young people were more depressed than The Olds because of “wokeness,” as he claims, then we would not see a pre-existing difference between liberals & conservatives as far back as 2005. In addition, we would expect to see Democrats pull away in their score for “depressive affect” starting in 2016 — which we don’t see. The lines for liberal men and women also increase at similar rates. Here is a chart of the usage of the word “woke” in Google searches since 2004:

So is wokeism making young people depressed? Probably not. But spending 6 hours a day on TikTok probably is.

3. Reassuring evidence that voters can be persuaded by facts

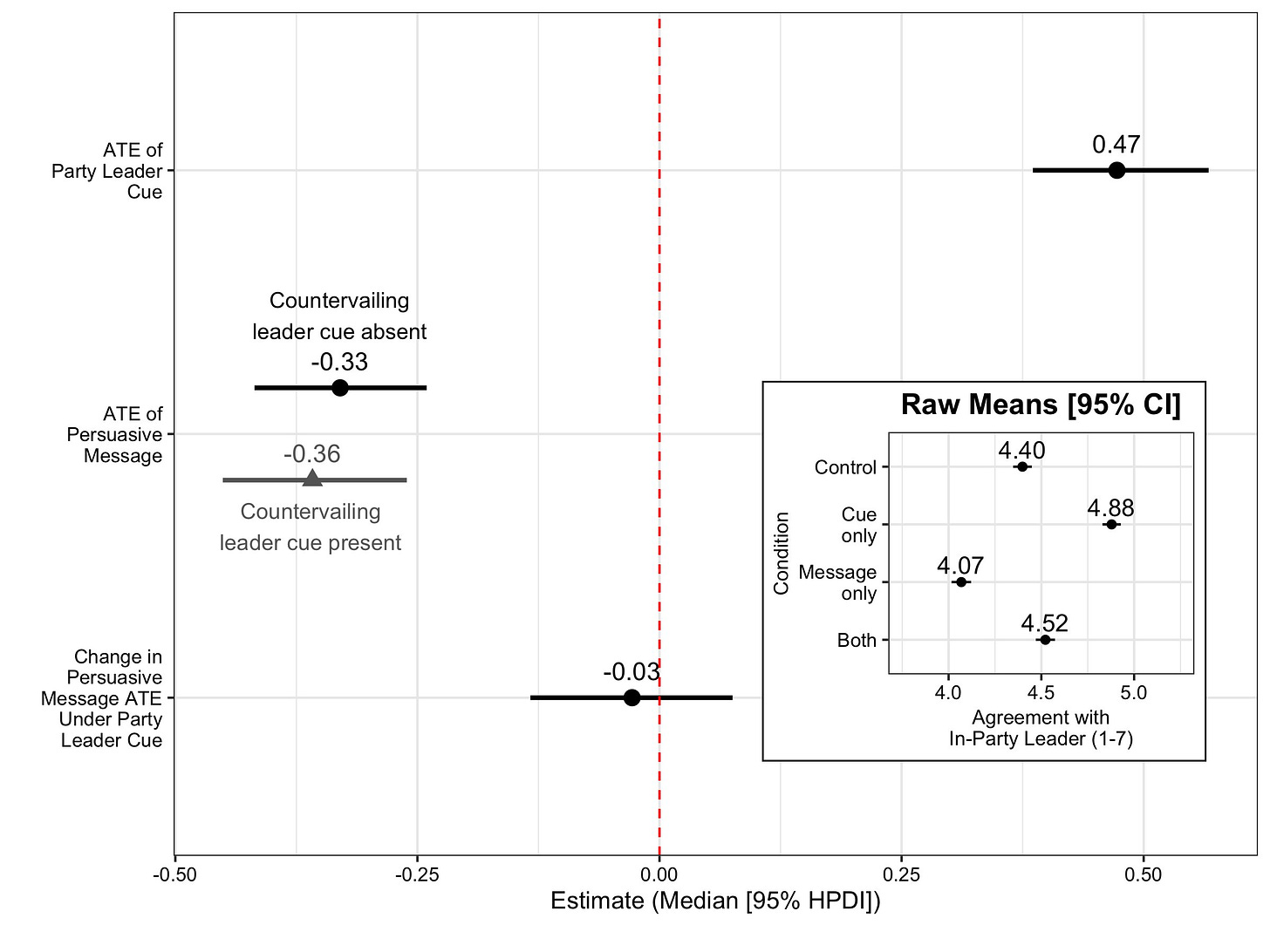

For the last link this week, let me recommend this new article published by political and brain scientists Ben Tappin, Adam Berinsky, and David Rand in the journal Nature Human Behavior. In their paper “Partisans’ receptivity to persuasive messaging is undiminished by countervailing party leader cues” they find “no evidence” for the popular hypothesis that partisans — people with strong Democratic or Republican identities — are less receptive to new information when their opinion leaders (in-party presidential candidates or co-partisan talking heads, for example) take opposing stances.

“It is widely assumed that party identity/loyalty exert a powerful influence over information processing,” Mr Tappin wrote on Twitter, “including reasoning. Thus, e.g., Cohen (2003) suggests party cues can ‘reduce to nil’ the impact of other information.”

But they don’t find evidence for this (graph of findings below). Instead, the authors find process equal information from the persuasive message, they just “stack” (my paraphazing) the party leader cue on top of it. That means that intervention from opinion leaders doesn’t cause people to ignore new information when they hear it… they just change their minds after, I guess?

This is a potentially optimistic finding, depending on how much you want to read into it. The paper suggests that the average modern American is not a strictly partisan being, though they may be an overwhelmingly one.

That’s it for this week’s top links. Thanks for reading and being a member of the community supporting this newsletter. Consider sending a free trial to a friend you think will enjoy the subscriber-only content.

Have something interesting for me to write about? Send it to me on Twitter or via email (I’m gelliottmorris@substack.com).

Have a great week,

Elliott