Kevin McCarthy's flailing bid for Speaker of the House is not (only) about ideological differences

Concerns over process, rather than politics or policy, are the main reason for his woes

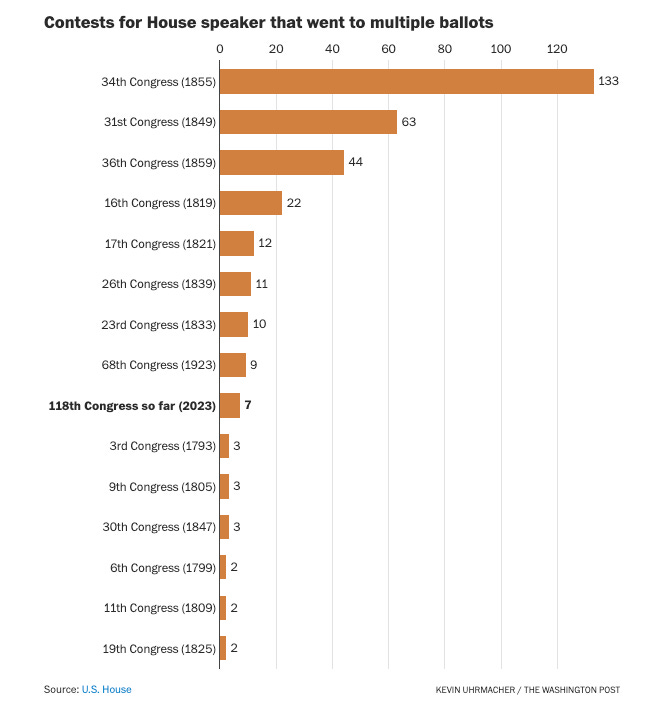

The website of the United States House of Representatives tells me there have been 14 occasions when the election for Speaker of the House has taken multiple ballots. The first was in 1793 — the third Congress ever — when it took members three ballots to cast a majority of ballots for Speaker. Others have taken many more successive votes, such as for the pre-Civil War 34th Congress (meeting for the first time in December 1855). Then, anti-Democratic members won a majority of seats but no single party controlled House due to the disintegration of the Whigs. Some of those members became Republicans, others took up with the Know-Nothings. It took two months, 133 ballots and a rules change to elect the Speaker via plurality to resolve the impasse.

Here is a chart of other multiple-ballot elections from Speaker courtesy of the Washington Post:

This year’s election for Speaker of the House will become the 15th such occasion. As I write, a majority of the chamber’s representatives have failed for a ninth time to settle on a House leader. Causing the deadlock are some 20 Republican members of Congress who are opposed to their party’s leader, Kevin McCarthy, becoming their Speaker. All Democrats have now voted nine times in favour of their own leader, Hakeem Jeffries, to become speaker. As of writing the last vote was 212 for Jeffries, 201 for McCarthy, and 20 for other members (including Byron Donalds, a little-known representative from Florida).

The media has been quick to note that so-called “#NeverKevin” Republicans are all members of a caucus of House GOP lawmakers called the Freedom Caucus, though not all Freedom Caucus members (there are 54 of them) have voted against McCarthy. Reporters have also called the holdouts “extremists” and “hard-right lawmakers,” contrasting them with the supposedly “moderate” and “establishment” members supporting McCarthy. While there is some truth to the existence of ideological divide, another force is driving the impasse: process.

Take the Representative of Arizona Andy Biggs, who has led the party coup against McCarthy. He announced his own bid for Speaker last year, saying on Twitter that he was running “to break the establishment. Kevin McCarthy was created by, elevated by, and maintained by the establishment.” Yet Biggs and the other detractors have pointed out very few policy differences with McCarthy. On Wednesday night, in a big blow to the party leader, he gave in to three demands of the so-called “radicals”:

As of Thursday afternoon, such concessions have not won him any more support. Process considerations persisted: Ahead of the ninth ballot, #NeverKevin representative Matt Rosendale of Montana argued Republicans should pick a Speaker who would facilitate “healthy” and “collegiate” debate about all the issues that all American voters would like addressed. “Under the current leadership construction,” Rosendale said, “the leadership negotiate 15 to 20 pieces of legislation that one Democrat and one Republican discuss momentarily and then say the magic words: ‘without objection, we will pass this with unanimous consent’”. Rosendale proposed rule changes that would curtail the powers of leadership, similar to demands made by his peers.

The first stalled Speaker bid during a (polarized) two-party system

Students of history and political science alike may note that extra-ideological factors are common in determining who wins leadership elections. Speakers have included both members near the middle and extremes of the distribution of ideological scores for their party, for example.

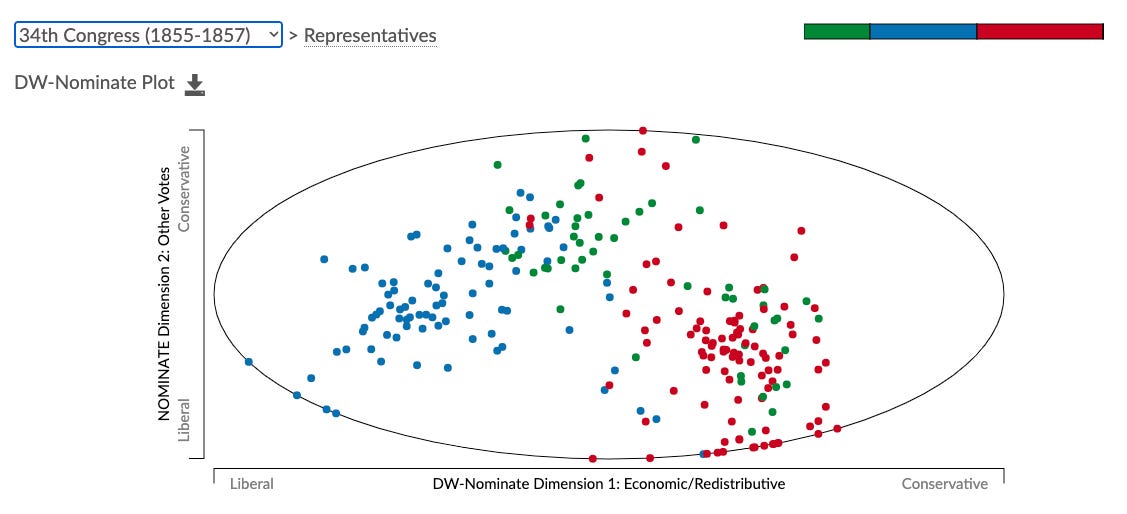

Yet what is different this time is that the two-party system has created a vast ideological divide between the parties — and relative uniformity of beliefs within them. McCarthy’s supporters and detractors alike share most of the same beliefs. The following chart, for instance, shows the ideological positions of House members in the 34th Congress:

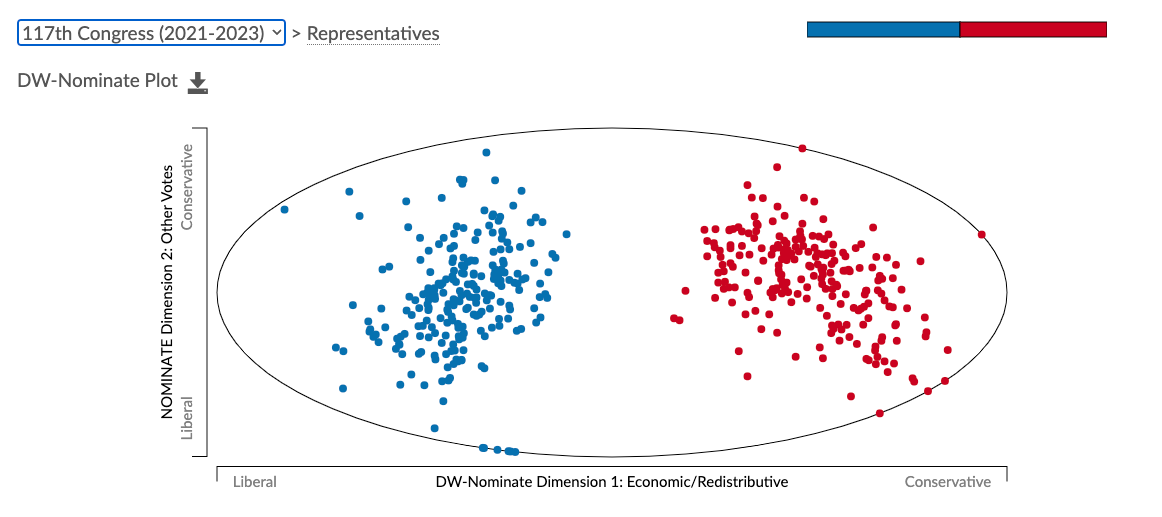

And here is the distribution of the members of the 117th Congress:

The vast majority of Republicans have also voted against Joe Biden the vast majority of the time; many anti-McCarthy members are even relatively more pro-Biden than his supporters. Representative Biggs voted with Biden 5% of the time, for example, according to a tally from 538, while Marjorie Taylor Greene, who is supporting McCarthy due to promises of committee assignments if he wins, has voted with him just 3% of the time.

As another example, here is what the House looked like in 1923, the last time representatives needed more than one ballot to elect the speaker. Note the Republicans and Democrats were much closer together on the left-right dimension of ideology, and also took a wider diversity of votes on other subjects of debate. Recall that there were liberal Rockefeller Republicans and conservative Southern Democrats in the House at this time — two groups that no longer exist.

Below, I have highlighted the group of Republican representatives that we would expect a priori to vote against a “moderate” speaker for the House. You may be forgiven for assuming all of these members have voted against McCarthy’s bid for speaker; only half of them have:

What we have in Congress today is not an ends-against-the-middle battle for control of the House. We have one characterized by many different demands — about personality and politics, but mostly about the various processes of legislating — being made of an establishment politician by an unruly gang of mostly, but not entirely, outsiders.

That is an important difference from the way the media characterizes the battle, and indeed from most other battles within the Republican caucus today. But it is an important and profound difference — one that could have profound impacts on the way the House operates in the next Congress.

In 1855, after 133 ballots, House members ultimately settled on Nathaniel Banks of Massachusetts as their speaker. He united a free-soiler Congress against a Democratic president and Senate.

Great post. I'm about to forward it. But, if you want a whole book full of analyses of speakership votes in terms of nominate scores, check out our book on the subject: https://press.princeton.edu/books/hardcover/9780691118123/fighting-for-the-speakership.

Elliott, with all due respect because I like your stuff, your analysis looks like so much mental masturbation. To me, they key elment here is 'who are the big lie election deniers?' Their goal is to show that the legislative branch is broken, and they will break it some more to prove it. There is no 'American people' they are trying to serve, they are serving their paymasters and the voters of their little fiefdom -- one of 435. They rail about 'big government', and they are there to throw sand in the works so it grinds to a halt. Act 1: Posture, postulate, and obstruct the speaker election. (At some point, their staff may ask 'when are we going to get paid'.) Act 2: Take their newly won power and obstruct any meaningful governing. Act 3: Continue the political theater with their absurd oversight histrionics. Act 4: Fail to address the debt ceiling in any meaningful way. Act 5: When everything crashes, convince the voters in their fiefdon that they are a hero, and that it was the 'other guys' who did it.

Insideous by design. Create a weak legislative branch, and augur the advent of a strong leader.