Is Trump’s electoral-college advantage slipping?

Midwestern voters have been just barely more likely than the average American to sour on the president recently

The electoral college is an anti-majoritarian institution that enshrines America’s history of slavery, gives small but durable advantages to candidates who poll better in exurban and rural areas and disproportionately magnifies the voices of people who just so happen to live in close states.

In 2016, this unique and antiquated mode of electing presidents delivered Donald Trump the presidency even though he lost the popular vote. But the advantage does not always flow to Republicans. In 2008 and 2012, Barack Obama actually could have won the electoral college with a popular-vote minority.

Who will the electoral college favor this time around? So far, it has seemed like the patterns of the 2016 election would hold. Back then, Trump won Wisconsin, the “tipping-point” state, with a two-party vote share about 1.5% below his national vote share, or a difference in his raw vote margin just about 3 points (he lost by 2 points nationally but won by one in Wisconsin).

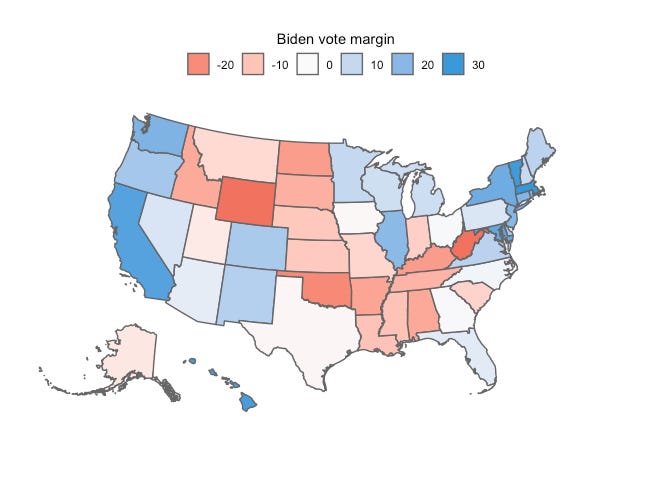

We can quantify Trump’s electoral-college advantage for 2016 by repeating this exercise, but by using current poll numbers instead of actual results (as they do not yet exist). We could do some fancy math for the polls but for now I’m just going to rely on the numbers from my toy election model, which are calculated using a simple average of the last two months of polls, with each weighted by sample size and the resulting average adjusted toward a dynamic benchmark based on polls in similar states. Those averages currently look like this:

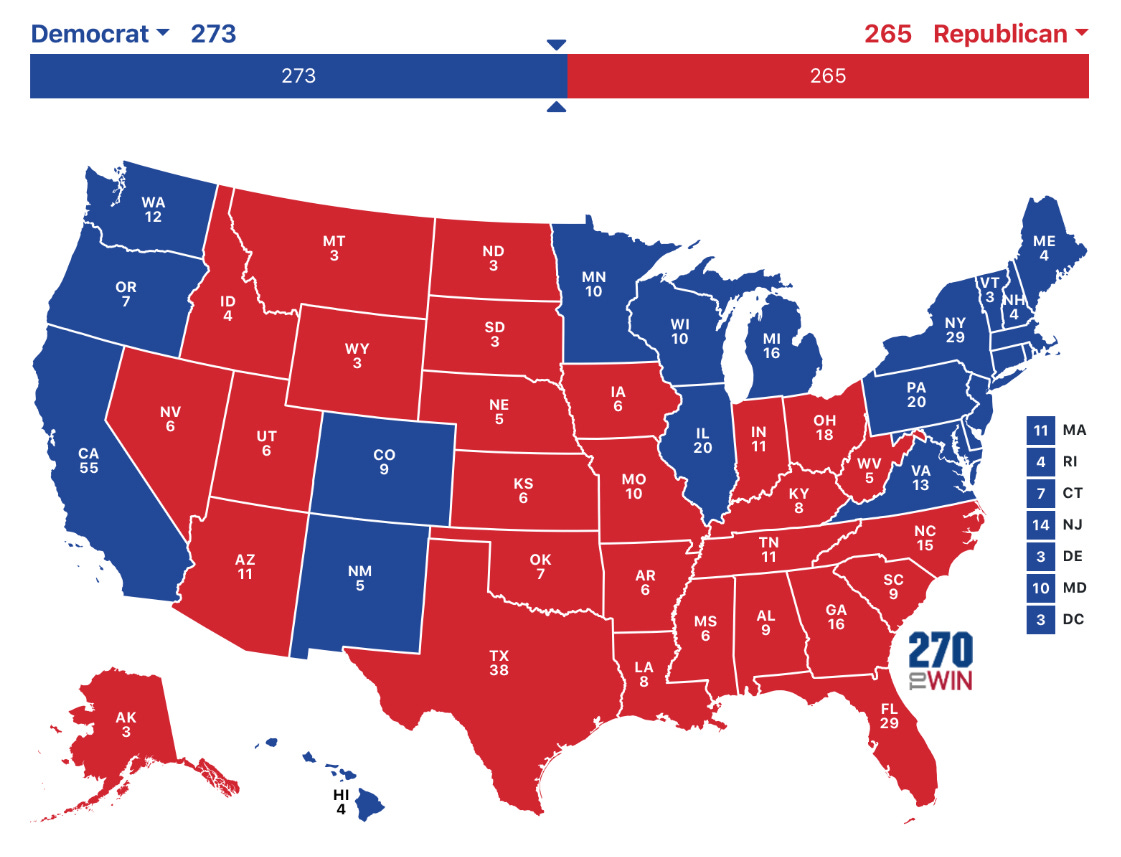

And we can figure out which state will tip the election toward Biden or Trump (the so-called “tipping-point state”) by ordering the states by Biden’s win margin and adding up their electoral votes, tallying them up until he wins 270. The state that provides the 270th right now is Pennsylvania. Here’s a map showing all the states where Biden’s margin is currently larger than in PA as blue, and the rest red. This is not what the polls say right now but illustrates the base scenario Biden needs to pull off to win the election:

The steps to quantify the bias of the electoral college this time is straightforward from here. We just take Biden’s margin nationally and subtract his margin in Pennsylvania. Right now, that means we subtract 6 from 9 and can say that Biden needs to win the national popular vote by 3 points in order to win the electoral college.

That’s the exact same margin as in 2016!

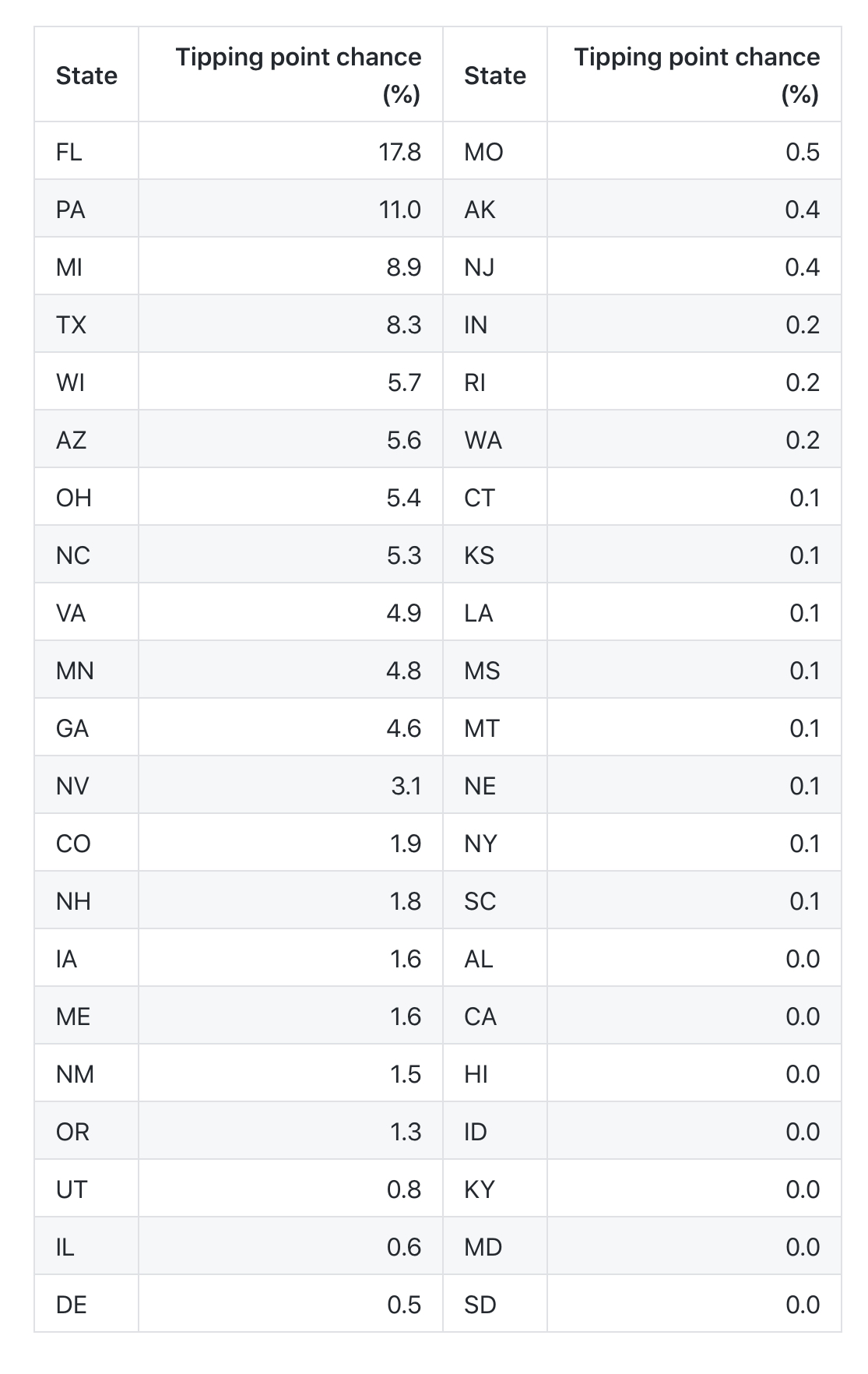

Using our computer we can take this one step further, however. Looking at just one electoral scenario gives us a false impression of the race; what if polls are wrong and a different state tips the election? Which state will that be, and how far to the left or to the right does it lean? If Trump wins the election instead of Biden, is the tipping-point state different? My toy model simulates 20,000 different scenarios to answer all these questions and offers a slightly amended answer to the question of electoral-college bias.

This table tells you which states we would expect to flip the election to Biden or Trump conditional on various amounts of polling error. Right off the bat you can see that it changes our answer to our main question: it says that even though Pennsylvania looks like the tipping-point state right now, once we add the chance for polls to be wrong, Florida jumps ahead as the most likely tipping-point state. And Texas creeps up to a surprise fourth place in this ranking:

The alternative measure of bias is calculated in a similar way. Instead of counting up how many times each state flips the election, we can take each of the 20,000 simulations and extract Biden’s margin in the tipping-point state and his margin nationally and calculate the average difference between the two. Right now, that number is 1.7 percentage points—a slight decrease from the 2.5 percentage point reading I get if I plug in the polls from 2016 into this simulator instead of the 2020 data.

This analysis has shown that the electoral college still gives Donald Trump an advantage over his Democratic opponent Joe Biden. But just how large that advantage is changes by the day and depends on how you calculate it. Some signs suggest that it has shrunk relative to its 2016 level. That would be good for democracy, but the institution still represents a clear issue to people who want to live in a country governed by the majority.

My worry about the polls is the wording of the questions. For example, suppose you are interested in what determines whether a person supports or opposes "Trump's handling of immigration”? Responses on a Likert scale:

1. Strongly Agree.

2. Agree

3 .Disagree

4. Strongly Disagree.

( 0 =Not applicable, 8 Don’t Know, 9 Not Answered are all coded as missing values.)

Should this be modeled as an OLS model where the dependent variable is a continuous scale indicating increasing disagreement, from 1 to 4?

Or as an OLS/ Linear Probability Model for the probability of Agree vs Disagree, where Strongly Agree is collapsed into Agree, and Strongly Disagree is collapsed into Disagree?

Or as a Logistic Regression for the probability of Agree vs Disagree, with the same collapsing?

All in all, garbage in, garbage out is my view on polls.

The most important fact about the electoral college is that all states except smallish Nebraska and Maine maximize their power by casting 100% of the electoral college for the popular vote winner. This could be characterized many ways but not as "anti-majoritarian," as it over-rewards the majority in the state.

Presumably, states would also maximize their power under a popular vote system by maximizing the vote differential in their state between the majority party's presidential candidate and the alternatives. How they might do this we already know since the end of Reconstruction and recent moves to disenfranchise the opposition. With the electoral college, such moves have a limited impact, only being important in large competitive states, especially the places most able to combat the problem -- Florida in 2000 only gives you an appetizer of the problems to come with a never-tested popular vote system.