How public opinion polls shape Supreme Court decisions

Notes from Ketanji Brown Jackson's confirmation hearings and polls on same-sex marriage

Today’s subscribers-only post is about Ketanji Brown Jackson’s Supreme Court confirmation hearings. They present a rare opportunity to write on the intersection of current events, polls, and an excerpt from my upcoming book.

As a refresher: On Thursday, Ketanji Brown Jackson, Joe Biden’s nominee to fill the seat on the Supreme Court that will be left open by Stephen Breyer when he retires this summer, finished a week of testimony to the Senate judiciary committee. The same group of senators advanced her nomination for the federal circuit court of appeals last year. On the Senate floor, 53 senators (50 Democrats and 3 Republicans) voted to confirm her.

All of this suggests the hearings for her Supreme Court nomination might largely end up a formality. If Jackson is qualified for a position on the appeals bench, we’d assume she would make a good Supreme Court justice, too. (Of course, that’s conditional on the members of the prior hearing doing a good job in their research and questioning.)

But our politics are anything but rational. At many points, the committee members acted more like they were cutting fresh political ads than conducting an inquiry into how Jackson would perform in her new capacity as a justice. For instance, several senators spent much more time asking if Jackson believed in critical race theory or implying she supported pedophiles than asking about her judicial philosophy and methodology. Lindsey Graham, who voted to put Jackson on the appeals court last year, stormed out of the committee chambers after a lengthy bout of shouting at Jackson for not saying Americans who Google search for child pornography should go to prison for 50 years. (The judge maintained her past sentencing was in line with the existing statute.)

One exchange centered in part on the role public opinion plays in judicial activism. Because this blog is about similar themes, that’s the one I wanted to write about today.

On Tuesday, John Cornyn, Texas’s Senator, launched into a series of questions about how the Court decides to upend its precedent. He cited positive examples of this, such as the Court overruling itself on Dred Scott v Sandford and Plessy v Ferguson, two cases that invalidated parts of the Missouri Compromise and held African-Americans could not obtain citizenship, and established the “separate but equal” doctrine for race-based discrimination, respectfully.

Cornyn was not so happy with the court’s 2015 decision in Obergefell v Hodges, the case which allowed same-sex couples to obtain marriage licenses in any state under federal law. This, Cornyn argued to Ms Jackson, was judicial activism which opened the door for discrimination against people with religious objections to same-sex marriage. He said the matter should be left up to the states, 33 of which had popular support for “traditional” definition of marriage, according to Cornyn — and asked how the Court could come to such different formulations of due process and other federal rights over time

This is, however, a misreading of history. The error here is very important. Cornyn’s invocation of the 33 states that banned same-sex marriage in 2015 gives a dramatically misleading picture of public support for equal marriage at the time. That has implications for how we study the influence of public opinion on the Court’s decisions. So, here are the data that correct the record:

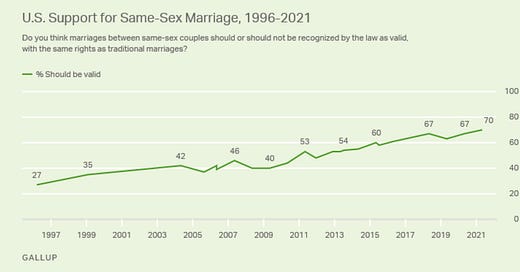

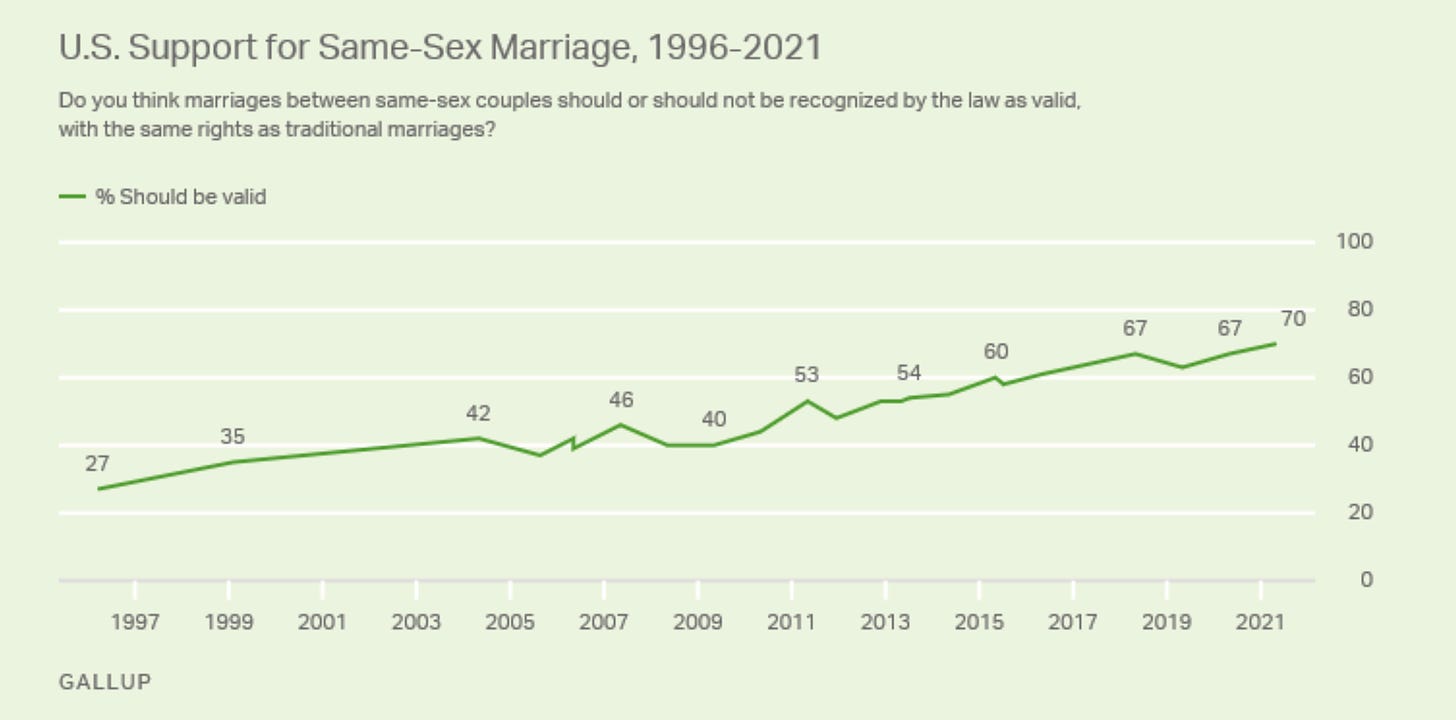

According to polling from Gallup, by 2011 a majority of US Americans agreed with the statement that “same-sex couples should be recognized by the law as valid, with the same rights as traditional marriage.” In a similar vein, a 2013 poll from YouGov found a plurality of 48% of Americans wanted the Supreme Court to invalidate the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), which outlawed the practice. That represented a ground shift in support for gay couples; just 2 decades prior, only a quarter of Americans wanted to legalize their marriages:

The issue here is not just that Cornyn misrepresents Americans’ support for same-sex marriage. The revisionist history on public opinion also serves some conservatives’ argument that the Supreme Court should not have struck down DOMA because a majority of people did not want it to. It is tempting, of course, to argue the court should be bound by some degree of democratic accountability, despite the corrective role the judiciary is supposed to play.

That raises a final question that is worth briefly touching on: How does the court actually factor public sentiment into its decisions? There are broader case studies available, but some clues come from the justices’ writings around the time of Obergefell. Here is a relevant excerpt from the introduction of STRENGTH IN NUMBERS:

Public opinion polls have also been instrumental in shaping Supreme Court decisions. When the Court in the 2013 case Hollingsworth v. Perry took up a challenge to a California law that prevented same-sex marriage, polling from Gallup showed marriage equality garnered only a bare majority of support from all American adults. At the time, the liberal justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg implied that a judicial solution on marriage at that moment could provoke a backlash to “momentum” that had been building for the cause, as she claimed the legalization of abortion under Roe v. Wade had done in the past. A poll conducted by YouGov in 2013 revealed 48% of Americans thought the Court should overturn the Defense of Marriage Act, a 1996 law which defined marriage as between one man and one woman, compared to 39% who thought it should be upheld.

By the time the Supreme Court granted same-sex couples the right to marry in Obergefell v. Hodges in 2015, 60% of the country supported it, according to Gallup’s polling. Justice Anthony Kennedy noted the trend in the majority opinion of the Court: “Judicial opinions addressing the issue have been informed by the contentions of parties and counsel, which, in turn, reflect the more general, societal discussion of same-sex marriage and its meaning that has occurred over the past decades. This has led to an enhanced understanding of the issue.”

. . .

The evidence in Obergefell is of the Court consulting opinion in debating (a) whether to take on cases and (b) the facts of those cases, but notably not in analyzing the merits of each side’s arguments. That runs counter to what a lot of people expect to get out of the justices — judicial activism for partisan causes they care about — but indicates the Court is still bound in some way to a higher power, which can steer it in general directions and prompt it to re-evaluate laws and precedents over time.

To be sure, that is not to say that all the public’s opinions are good. But when the facts of life change the understanding of an issue, and how the Court might rule, it is good we have a tool to elevate the will of the people to the Court. I’m talking, of course, about the polls.

If you want to read more about how the Supreme Court is bound to the public, I recommend reading Barry Freedman’s book The Will of the People — or at least this review of it.

Seems to me the SCOTUS' use of public opinion polls is something that has to be corralled by specific regulations, which only the court itself can set. The court must not ever be unaware of the issues of the day. Bounding that awareness means something to me it may not mean to the judges. And as we frequently discuss here on your newsletter, polls are shaped by how the questions are phrased and who gets polled.