How covid-19 exacerbates America’s urban-rural divides 📊 April 19, 2020

Commentators on the right have been quick to blame cities and liberals for transmitting the virus. As it spreads to rural areas, they do more harm than good.

Welcome! I’m G. Elliott Morris, a data journalist at The Economist and blogger of polls, elections, and political science. Happy Sunday! This is my weekly email where I write about politics using data and share links to what I’ve been reading and writing.

Thoughts? Drop me a line (or just respond to this email). Like what you’re reading? Tap the ❤️ below the title and share with your friends! If you want more content, I publish subscriber-only posts 1-2x a week.

Dear reader,

As I sit here writing this newsletter tonight, it is hard to see the light at the end of the tunnel. At a time when Americans desperately need to unite together to defeat a common enemy, it is easier than ever to see what divides us. And it is easy to see the very real, life-threatening dangers of those divisions.

For many of you, I’m preaching to the choir in begging that you stay indoors if you can, out of harm’s way and with your loved ones (at a time when they are no doubt relying on you). I am not a doctor or a psychologist, but I do enjoy talking with y’all—if you need company, feel free to send me an email. We can talk about politics, data, covid or any other adjacent subjects. I could honestly use the human “contact”.

How covid-19 exacerbates America’s urban-rural divides

Commentators on the right have been quick to blame cities and liberals for transmitting the virus. As it spreads to rural areas, they do more harm than good.

We have entered the second phase of the coronavirus pandemic. It has spread well beyond the cities, where it was initially seeded. New hospitalizations and case growth have slowed in New York City and other high-density metros while accelerating elsewhere. The IHME model projects than New York, by far the hardest-hit state, will see its peak in deaths in 3 days’ time. But residents of Tennessee will face the worst of the virus in 5; people in Nevada and Wyoming will be on high-alert for at least another 12; residents of Wisconsin will wait 14 more days until their peak; and Iowans will face the peak in nearly 3 weeks when as many as 80 people per day could be dying from the disease.

Yet as covid-19 moves beyond the cities to suburbs and rural America, it will encounter a larger number of unserious, unprepared and vulnerable inhabitants. A vocal minority of Americans are now defying quarantine orders, taking part in densely-populated rallies and railing against state governments for curtailing their freedoms—when they’re actually actively trying to save their lives.

This resistance will extend the lockdowns beyond what is necessary. The curve will not be as flat as it could be. More mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers, wives, husbands and especially grandmothers and grandfathers will die than should. Let me put this bluntly: foolish, ideologically-driven resistance to lockdown measures (which, yes, are economically and mentally harmful beyond what many Americans have ever faced before, but by no means more important than human life) will get people killed.

But there are a few other angles to this virus that the social scientist in me has not been able to overlook ever since the beginnings of covid-19 in America. The virus has only further exacerbated America’s urban-rural divide—not only a geographic division but cultural, political, religious and social cleavages as well.

Over the last couple of weeks, such divisions have been proudly and loudly put on display by the commentariat right. Patrick Ruffini, a Republican pollster cited the virus as a reason why urbanism and mass transit systems are bad:

Patrick likes to troll on Twitter, but his take also bears some semblance of sincerity—it’s not hard to infer based on the opinions of his adjacent Republican elites that he may actually feel this way.

Take Erick Erickson, a popular radio talk-show host and mouthpiece of the Christian right who penned an entire essay just yesterday on why cities might cosmically deserve what they’re getting. In “A theology of cities and the pandemic” he writes:

It is no coincidence in scripture that the first city came from Cain, filled with the inbred product of his and his sisters’ relations. Time and time again, God’s people are poorer and in less urban areas. Bad things happen everywhere, but a lot of bad things are magnified in urban areas. Jesus died at the hands of an urban mob. Babel’s residents decided they could rival God. The division of Israel into the Northern and Southern kingdoms brought wealth and prosperity and a growing urban core to the Northern Kingdom while the Southern Kingdom of Judaea, outside of Jerusalem, remained largely agricultural. Scripture says God used prosperity and cycles of famine and pestilence to try to cajole the urban dwellers to repent, but they did not. As a result, this life is the best the unsaved will ever have and this is the worst life the saved will ever have.

I don’t think he would ever admit it, but Erickson is pretty transparently implying that the covid-19 pandemic is a plague sent by God to punish the sins of urban-dwellers. If only they lived out in the suburbs or on farms, where God meant for them to live… He says:

The virus has reminded us that family matters and living alone makes it harder in times of calamity. It has shown us that the secular cures of the age like mass transmit and small or nonexistent families make us more vulnerable. It should be showing us that abandoning our elderly to be taken care of by others abandons our obligations to them.

And, emblematic of the politics of this “theology” of cities, Erickson wants you to know he also hates reusable shopping bags:

The mad dash to force us all to carry reusable shopping bags hit a brick wall with the virus.

And he doesn’t like mass transit either:

I have seen the increasingly secular left in this country increasingly belittle rural areas and the people of flyover country. They have insisted we all move to cities. Their movies have, interestingly, portrayed urban areas as manageable hellscapes while rural areas are abandoned and filled with murderous savages if habitable at all. They have insisted we embrace mass transit, trains, bikes, small families or singleness, and reusable shopping bags.

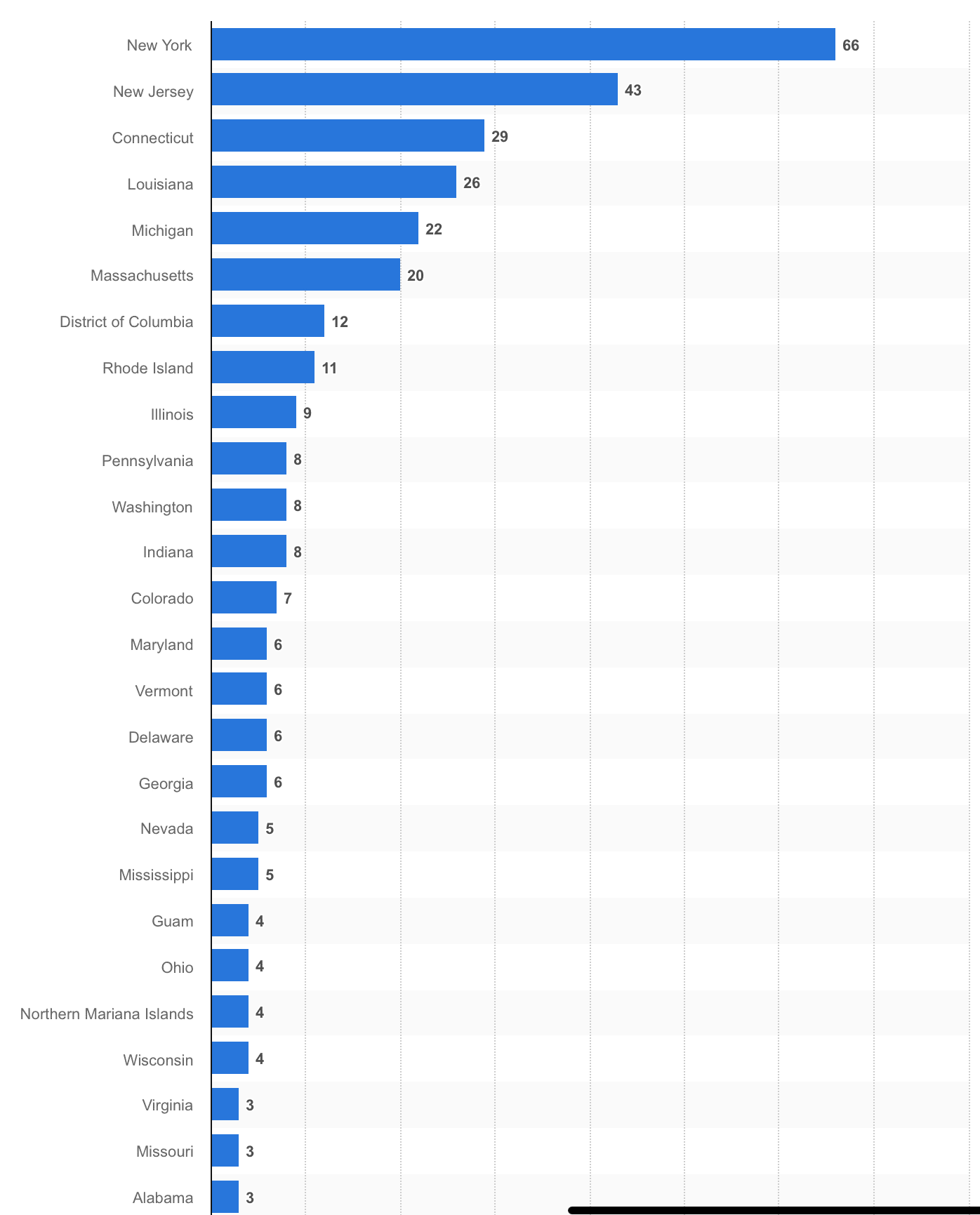

If only you need proof that the cities are hellscapes to which God has explicitly sent the coronavirus to punish sinners, Erickson provides for you a graph of per-capita cases of covid-19 by state. Denser states have more infections. This must be evidence of their devilishness (not, you know, both the features and bugs of living close together).

I am not here to debate the merits of living in a city versus the exurbs. I’ll note that there is an interesting geographic-political-religious divide in the response to covid-19. Mainline sects of Christianity have seemed to take the threat a bit more seriously than some more fringe evangelical groups. My church (I’m Episcopalian) has canceled all services for the foreseeable future, and I watched a live stream of Easter service from my living room. It was a sad reminder of the world we’re living in today. Last Sunday did not feel like Easter. But the (urban, yes) congregants I know have agreed that our lives are more important than gathering in physical union. And we’re taught that God is always present where we are—that we are the church, not some physical space. In contrast, a group of evangelical Kansans gathered for service a few weeks ago and nearly four-dozen of them contracted covid-19. Other sects in rural areas have filed similar complaints. A pastor in Lousiana faces charges after he kept his church open and even bussed congregants to service, endangering their lives.

Ruffini’s jokes and Erickson’s “theological” writings are stark reminders of the socio-political implications of a virus that has so far primarily taken as its toll people in urban areas. It is easier to treat unseriously a deadly disease you are isolated from.

Such unseriousness was put on display this week when rallies resembling the ~2010 tea parties swept the nation. In Lansing, Michigan (which appears to have had the largest one) maskless protestors spoke out against restrictions and business closures they argued were oppressing their economic freedom, endangering their liberties and rights as American citizens. “Open up the barbershops”, one protestor said, “I deserve a haircut”. President Trump tweeted in support of these rallies. One of the subjects I studied in college was America’s foundings (1791—1804, to be specific), and as Erickson’s writings remind me of Thomas Jefferson’s treatises on the political and libertarian fruits of agricultural labor and rural livelihood, so too do these political protests remind me of the type of needlessly factional thinking that our political architects like James Madison and Alexander Hamilton warned us to be cautious of.

The response to covid is geographically divided not only because of our religion but also because of our politics. That much is evident today; More Republican-leaning areas were slower to adopt social-distancing restrictions than cities. This could be because they are also more likely to be less educated and more distrusting of scientists and experts, but also because Americans’ tribal thinking today forces them to follow the (political) leader, particularly in regards to Mr Trump and the right. He resisted early warnings about covid. So did his supporters. He is pushing back against state governments and governors. So too are his supporters.

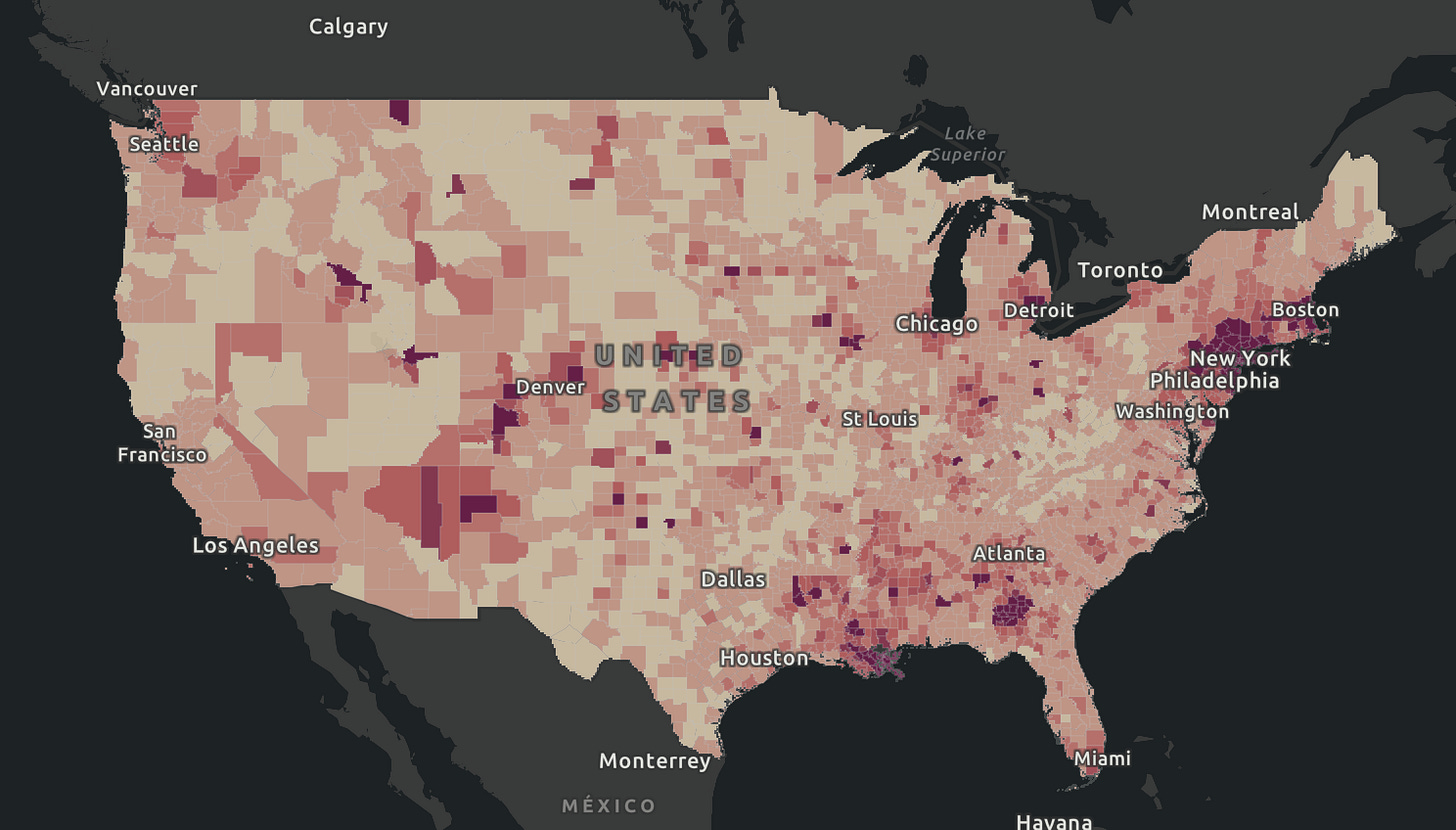

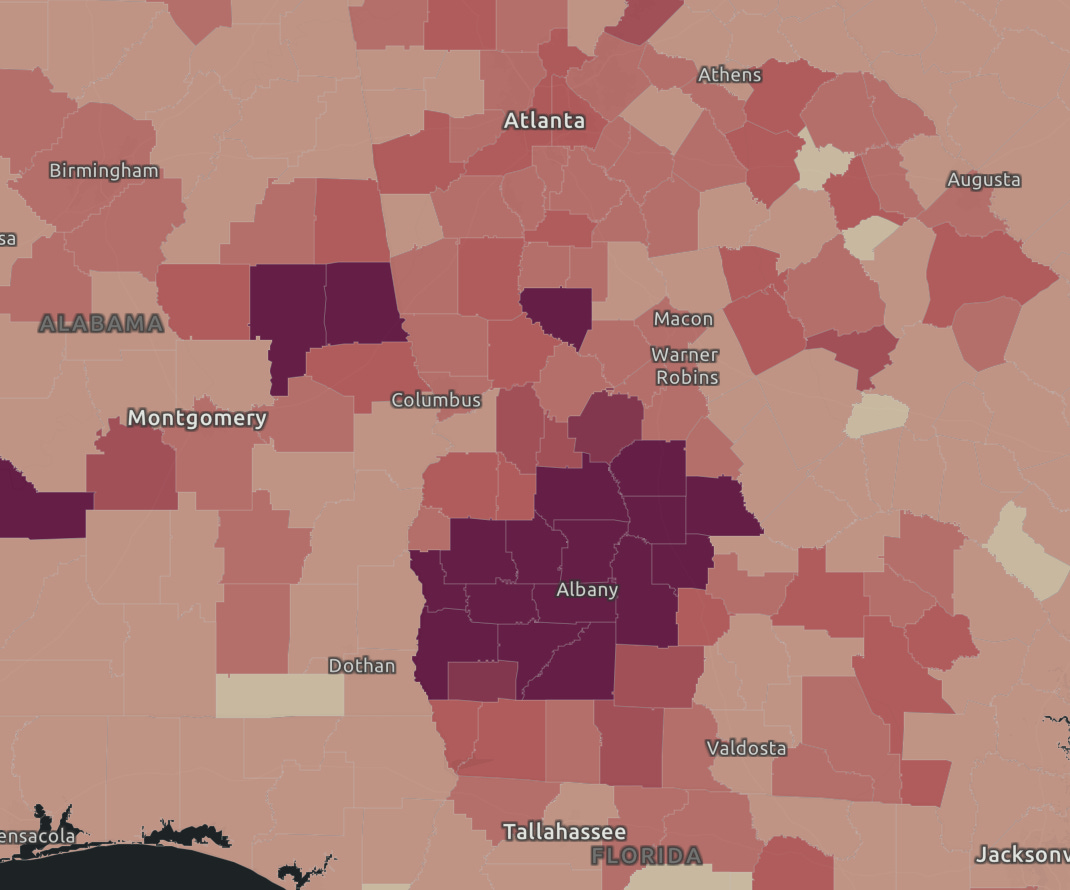

But unlike the political, religious and cultural right, the coronavirus does not discriminate based on your geographic location. Southwest Georgia is now experiencing one of the worst per-capita outbreaks of covid-19 across the country:

This area is predominantly rural (in fact it’s one of the most sparsely-populated areas east of the Mississippi) and very poor. Yet it’s outbreak rivals that of urban areas. The urban-rural divide evidence by the political commentariat class (particularly being pushed those on the right) is not proportionate to the reality of the disease.

This will all leave America’s suburban and rural residents, now experiencing the reality of the coronavirus in ways similar to how New Yorkers and New Orleanians have for a month, dramatically underprepared. They have written off the dangers of the virus, poked fun at urbanism and mass transit (and, by their logic, globalism and the international exchange of culture and ideas) and even implied that city-dwellers are to blame for their ill fates. This has distracted them from doing what they need to do, and the outbreak in Georgia proves it.

Throughout all of this, I have been worrying about our social fabric. The coronavirus is testing our sense of unity like never before. As I’ve written here, our geographic, political and religious divides are more on display than they have been in recent memory. So too are our divides in attention to different media sources and trust in experts. A shift to socializing by zoom and computers will further isolate people from different political stripes. I fear we are all bowling more alone than ever, at a time when we desperately need to come together. If we don’t, the coronavirus just might be the end of America as we’ve known it.

Posts for subscribers

April 16: Online and live-caller polls disagree about Biden’s lead over Trump. The pattern muddies the waters for election forecasters in 2020

Links and Other Stuff

America’s divide over covid

I’d suggest this piece from The Atlantic which has a lot more to say on the social and institutional consequences of the coronavirus.

Donald Trump’s durable electoral college advantage

This piece from Nate Cohn last week is also good, though I think it overstates Trump’s electoral college advantage. Cohn details that the divide between Joe Biden’s margin in the national popular vote and Wisconsin (a likely tipping-point state) is about 5 percentage points. My math reckons the actual disconnect between the two is closer to 1 or 2 points, and that Biden needs to win the national popular vote by just 2-3 percentage points to win the electoral college.

What I'm Reading and Working On

Y’all know the drill. It’s election season, so I’m running our models all day every day. I’m also modeling and writing about how covid-19 has affected poor people and minorities more than others next week so keep your eyes out for that. I sat down to revisit Lilliana Mason’s Uncivil Agreement, a book about how our politics became psychologically zero-sum and divided along identitarian lines—last night (as if I wasn’t depressed enough about America right now…). For “fun” I’m reading Hemingway’s In Our Time.

Thanks for reading!

Thanks for reading. I’ll be back in your inbox next Sunday. In the meantime, follow me online or reach out via email if you’d like to engage. I’d love to hear from you!

If you want more content, I publish subscribers-only posts on Substack 1-3 times each week. Sign up today for $5/month (or $50/year) by clicking on the following button. Even if you don't want the extra posts, the funds go toward supporting the time spent writing this free, weekly letter. Your support makes this all possible!

Long-time Twitter follower here and just did a subscription (starting following you in 2016 I think it was when you were still in school.) Quick question. I've been reading Dr. Rachel Bitecofer's articles and wondered what critiques or praise you might have for her analyses.

No question, but just wanted to see how you were faring this sundy- err Monday morning.