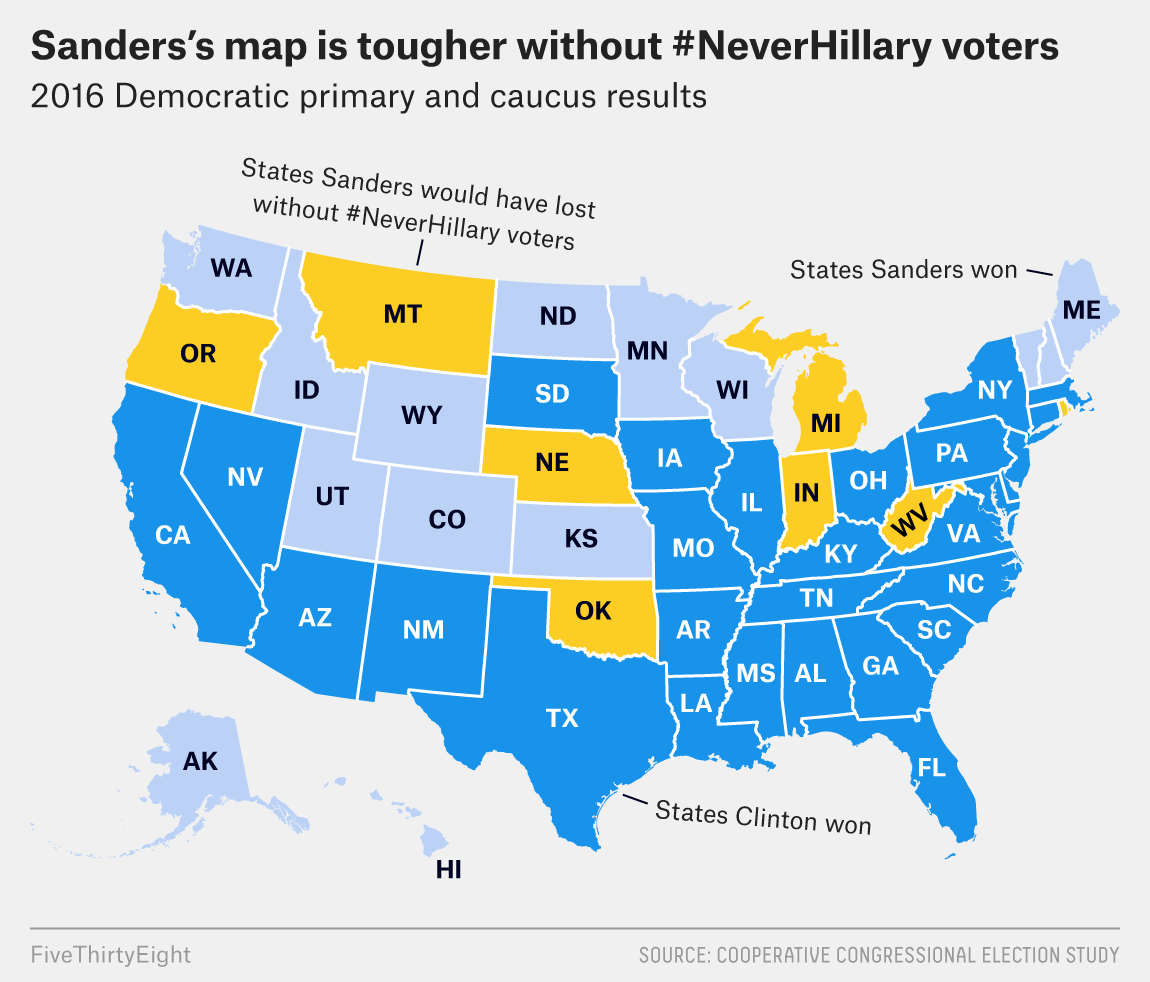

The Democrats’ presidential primary for 2020 began with a lot of skepticism about Bernie Sanders’s ability to win the Party’s nomination. One of the most dominant ideas propelling his bearishness was the theory that many of his 2016 supporters were simply #NeverHillary and wouldn’t vote for him this time around. Nate Silver estimated that Sanders would have won 8 fewer states last cycle if these anti-Hillary voters had a different candidate to vote for. His base nationally would have been 33%, rather than the 43% of the vote he actually got:

The suggestion at the time was that this deflated base would doom Sanders for 2020. This is partially evident now in that his vote share in national polls is much lower now than it was last time around. But look under the hood and you’ll find that the primary thus far has really played out much differently than originally expected.

Though Sanders’s support is worse relative to his 2016 performance, voters that were opposed to him last time around have clearly yet to agree on an alternative. The “moderate” lane of the primary—to the extent that “lanes” this simplistic exist—is split between Joe Biden, Pete Buttigieg, Mike Bloomberg, Amy Klobuchar and other lower-polling candidates.

This means that Biden’s vote share is lower than its theoretical upper bound. But while he’s ahead of Sanders nationally, important differences have emerged at the state level. Though Sanders isn’t doing any better in Iowa and New Hampshire than he was in 2016, neither are the moderate (or maybe “anti-Sanders?”) voters.

A split field gives an advantage to candidates with a high floor of support. However, presidential primaries do not occur all at once and in only a couple of states. The contest is spread out amongst many states and territories and happens over 5 months of contests. Support for nonviable candidates decreases as the race progresses, and, as they drop out, voters shift to contenders who can actually win the race.

This is always where we theorized that Bernie’s advantage would shrink, for two reasons. Another thing happens as the primary progresses: the electorate grows more non-white. In 2016, Sanders did well in Iowa and New Hampshire, thanks to particular strength among liberals, and in Nevada. But in South Carolina, his weakness among black voters became clear and he won just 23% of the vote to Hillary Clinton’s 76%. With such lopsided opposition from ~40% of the primary electorate, his 50-50 performance with whites wan’t enough to carry the day. 2016 could repeat itself this time around.

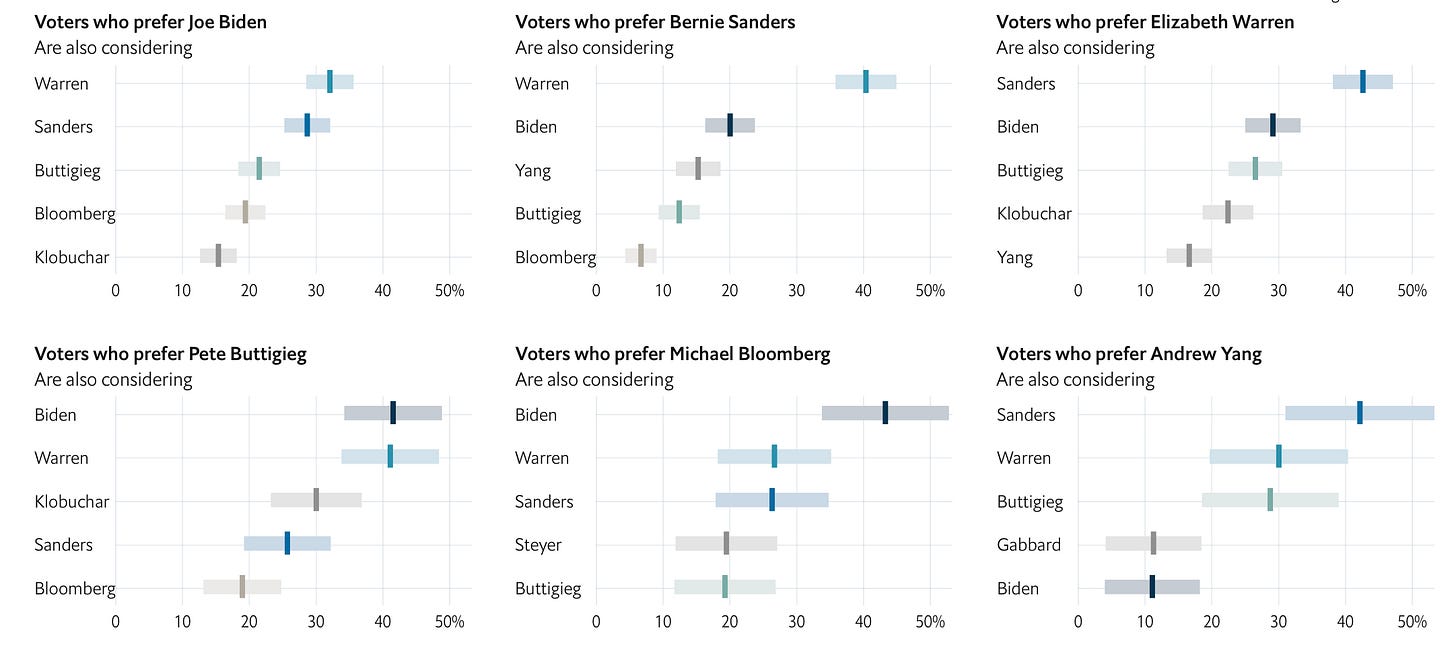

Second, as Silver’s analysis shows, there is a hard ceiling to Bernie’s appeal. He can possibly expand that ceiling by doing well later into the primary—thereby convincing Democrats of his appeal among non-whites—but that doesn’t look all that likely at the moment. As polling data show, Biden and Warren are more likely to consolidate support after lower-polling candidates drop out than Sanders is:

…

Evident in 2020 is that early theories of the primary have so far misfired. Sanders has done well despite a lower ceiling of support than his 2016 vote share implies. But votes opposed to his candidacy are split among multiple other candidates. He can win the primary by proving his viability among non-whites, and if his opponents don’t drop out. Contrary to what his current polling in early states suggests, that might yet be a tall task.

Editor’s note:

Thanks for reading my thoughts on this subject. And thanks for subscribing! Your membership adds up and makes all this newslettering possible (reminder: I do all this work independently). Please consider sharing online or with a friend; the more readers, the merrier!

As always, send me your tips about what you’d like to read about next, or your feedback otherwise. You can reach me via email at elliott@thecrosstab.com or @gelliottmorris on Twitter.

—Elliott