Grandma or the GDP?

A new paper illustrates the false choice presented by the president’s narrative

I have been particularly disturbed by the (far) right’s embrace of a troubling idea: the economy is worth more than grandma. Figures such as Dan Patrick, the Lt. Governor of Texas, Fox News hosts and President Trump have all adopted various views akin to the idea that the outbreak of covid-19 will have serious consequences for the economy that may not be worth the toll on human life. Trump this week said America was “not built to be shut down” and promised a return to normalcy by Easter.

Such optimism is foolishly misguided. The pandemic will almost certainly persist beyond mid-April. So will its economic consequences. Research shows that nations don’t fully recover from recessions (and we are certainly in the midst of one now) for years, perhaps even a half-decade. Before America gets there, things will probably get worse before they get better. Jobless claims rose by more than 3 million last week and are likely to be similarly severe in the next ones.

The president may be ignoring a simple, empirical truth about the economic consequences of pandemic: deaths cause more depressions than disruption.

That’s the conclusion from a new working paper circulated by researchers at the Federal Reserve and MIT. Authors Sergio Correia, Stephan Luck and Emil Verner have analyzed city- and state-level data on mortality from the 1918 Flu Pandemic and found that more exposed areas experienced “sharp and persistent declines in economic activity.” They find that non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) (such as school and church closures, bans on public gatherings, quarantines and restricted business hours) reduce both deaths from the virus and the length and severity of recessions.

The inquiry is interesting and well-specified. Correia, Luck and Verner matched up data on how cities and states responded to the virus (AKA how long they implemented NPIs, and how quickly they came about) with subsequent changes in employment, manufacturing and bank assets to estimate that the 1918 pandemic led to a roughly 18% reduction in economic activity in places with an average response. But there were significant differences in economic changes depending on how officials respond; “Importantly, the declines in all outcomes are persistent, and more affected areas remain depressed relative to less exposed areas from 1919 through 1923,” the authors write.

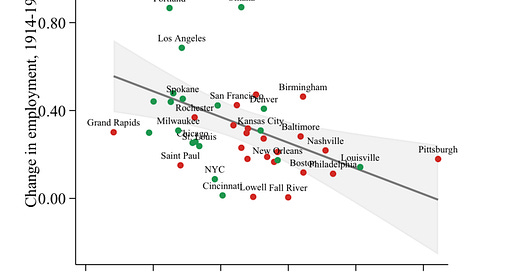

This figure summarizes the paper’s initial findings: a negative relationship between deaths and change in employment that is more severe in cities with weaker responses to the virus.

The authors draw more detailed inferences later in the paper. Quantifying the actual government response to the virus, they find evidence of a positive relationship between various measures of intervention and economic growth. The graph of those findings looks like this:

The authors write about these data:

A one standard deviation increase in the speed of NPI implementation increases output by around 5%. Likewise, a one standard deviation increase in the days of of NPIs in place increases output by approximately 7%. Altogether, this evidence suggests that cities that implemented NPIs earlier and more aggressively experienced more economic activity in the aftermath of the 1918 Flu Pandemic.

And they conclude their paper as thus:

Altogether, our evidence implies that pandemics are highly disruptive for economic activity. However, timely measures that can mitigate the severity of the pandemic can reduce the severity of the persistent economic downturn. That is, NPIs can reduce mortality while at the same time being economically beneficial.

…

Especially in light of the evidence, it is clear that the choice being posed by Trump, Patrick and others is a false one. The best way to combat the virus is to employ a robust government response to minimize contact between citizens and treat infected individuals. As it turns out, that’s also the best way to shore up the economy.