Finally, we have evidence pointing to a causal link between Trump support and covid-19 behaviors

Studies of surveys with multiple repeat interviews have taken us beyond speculation with cross-sectional polls and geographic observations

Let’s talk covid-19 today.

Since the onset of government-mandated lockdowns and social distancing measures related to covid-19 last year, epidemiologists and social scientists alike have observed a strong relationship between partisanship and pandemic behavior. Studies of many datasets, ranging from county-level cases and voting patterns to survey data to qualitative reports have found that…

… states with Republican governors waited longer to implement lockdowns and recommend masking than states with Democratic governors. They also lifted those restrictions earlier.

… individuals who reported voting for Donald Trump in 2016/2020 or called themselves Republican were much less likely to report social distancing or that they masked up at restaurants, the office, or the grocery store. Since we had survey data for this, we could run models that told us this was true even after controlling for relevant demographic and geographic data.

… Republicans and Trump voters are also less likely than Democrats/Biden voters to get vaccinated.

This is all concerning and suggests the GOP was behaving in a way that made them a threat to public health outcomes and so on. Yet this has, at least in my experience, been well covered by now. The New York Times published a chart of covid-19 cases and deaths in the most pro-Trump and pro-Biden counties just last month, and I have covered the survey data numerous times for The Economist.

What hasn’t been sorted out, however, is why these patterns exist.

One can imagine at least two possibilities here. The first is that partisanship and support for Trump are correlated with certain demographic traits or group memberships that are related to various covid-19 behaviors. Perhaps one’s membership in anti-vaccine Facebook groups stems from their lack of education and association with very conservative evangelical Christians in rural communities—and, in turn, decreases the probability that they’ll take the virus seriously and wear a mask. If that were the case it would be improper to say that Trump or the Republican party is causing, eg, vaccine hesitancy among Republican voters and Trump supporters. The former explanation would be consistent with some of what we know about other conspiracy theories and a more diffuse model of social interaction and attitudinal acquisition.

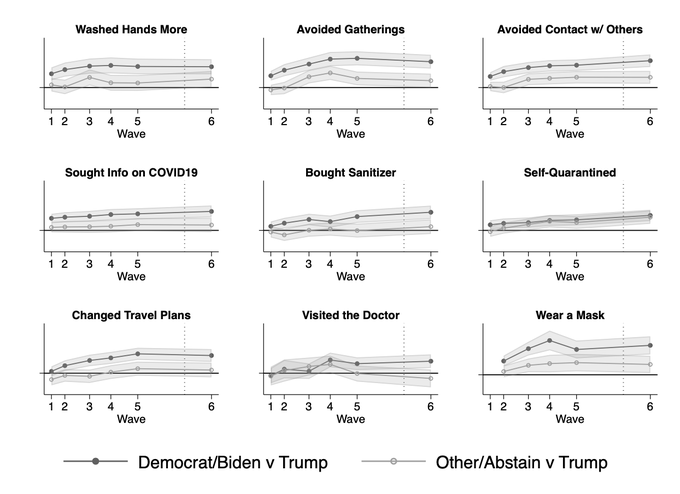

It turns out that the causal link is real, however — though scholars still include some caveats about having a messy time estimating the precise magnitude of it. A new working paper from Tom Pepinsky, Shana Gadarian, and Sara Goodman (all political scientists) circulated this week finds significant differences in covid-19 behaviors between Trump and other voters over time that can’t be explained by other demographic factors or other types of variation. Their paper looks at differences in behaviors among a “panel survey” of Americans (which is just a fancy way of saying a poll that asks the same people different questions over time).

Panel data are really cool! They could let you, for example, look at differences in, eg, the share of each racial/educational/income/etc demographic group that say they are getting vaccinated over time and compare them to trends among different groups of partisans (eg Trump v Biden voters). This is equivalent to, to add another example into the mix, comparing a president’s approval rating among white, Hispanic, and Black voters over time and attributing differences in the trend to something in the next/electorate/etc. But that’s just correlational!

So, to get nerdy, you can also run special time-series cross-sectional models on panel data that enable you to more precisely attribute causal relationships between data. In our case, that means Pepinsky, Gadarian, and Goodman trained models to predict various public health behaviors (such as wearing a mask or self-quarantining) dependent on their various demographic and political traits. Whether or not someone was masking in one week is a function of their traits in that week. The model tells us whether increases in masking are coming disproportionately from one group or the other.

And, indeed, they find that the divide between whether someone voted for Trump is a large and persistent predictor of whether someone was masking, changed their travel plans, said they were washing their hands more than average &c — even after controlling for the way other variables predict the same behaviors.

Here is the chart from their paper:

. . .

Now, again, this might not be surprising to you at all. Our prior understanding of the world, perhaps driven by our observations of Trump’s comments in the news or the way his surrogates talked about the virus early, was that the president was leading his followers to different health outcomes than people who were listening to scientists and public health authorities, such as Anthony Fauci. And the aforementioned data used for correlational studies strengthened that prior.

But now we have the receipts! This study finds that individual behaviors during the covid-19 pandemic were in large a function of someone’s support for Trump, not exclusively driven by some other factors. That’s important for policymakers to know as a matter of fact so they can address the source of disparities in public health outcomes. True, that was hard when the guy leading the charge against protective measures was the president of the United States, but no longer.

I guess the only question now is whether they will do something with this information. And maybe you and I can sleep easy knowing that this riddle has been solved and social science did something useful! 😉

OK, that’s the new public health research I wanted to share. More on politics and elections on Saturday.

Elliott