Donald Trump changed the GOP. But has he weakened it?

Most voters who were Republicans—or Democrats—in 2016 have stuck with their party

One of the more famous studies in political psychology found that people will defer to their party when deciding which policy positions they do or do not support. In his aptly-titled 2003 paper “Party Over Policy,” Geoffrey Cohen writes:

Four studies demonstrated the impact of group influence on attitude change. If information about the position of their party was absent, liberal and conservative undergraduates based their attitude on the objective content of the policy and its merit in light of long-held ideological beliefs. If information about the position of their party was available, however, participants assumed that position as their own regardless of the content of the policy. The effect of group information was evident not only on attitude, but on behavior (Study 4). It was as apparent among participants who were knowledgeable about welfare as it was among participants who were not (Study 2). Important alternative explanations for the obtained results, such as effects of heuristic processing and shifts in scale perspective, were ruled out (Studies 3 and 4).

Cohen’s findings echo a broader theme in social-psychology research which stipulates that people change their minds when they face pressure from their social groups. It makes sense that liberals and conservatives would adopt the “orthodox” view for their party if they didn’t have dearly-held contrary beliefs, similar to how I might start watching more sports if that’s something my friends and family do.

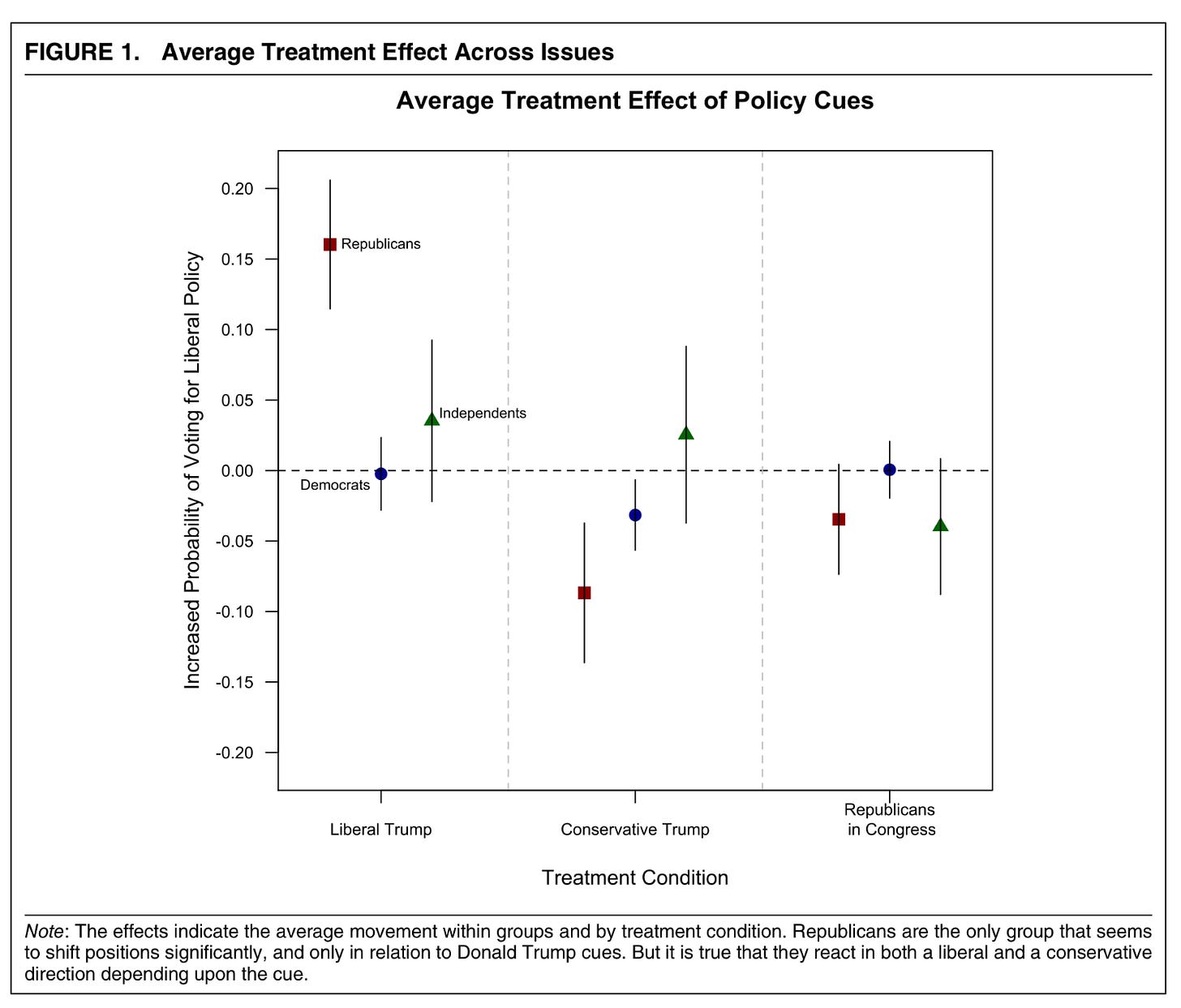

This research has recently been expanded to include analyses of how we listen to our political leaders, particularly President Donald Trump. In a 2018 study, Michael Barber and Jeremy Pope found that the president possessed a unique ability to change the minds of his Republican supporters. If he endorsed a liberal policy position, they found, GOP voters were more likely to support it as well. Trump holds similar sway over them when endorsing conservative policies:

One might thus infer that an individual’s identity with or against Trump has more influence over things like policy preference and vote choice than their party identification. But that’s not exactly how this works. Though party and vote choice Are highly correlated they are not the same thing. There are, after all, a ton of self-proclaimed “Democrats” in the Southeastern United States who are vehement supporters of the president’s. Republicans are largely—though not always—Republicans first, and they hold onto that identity even when some of their other attitudes change.

It has therefore always been very surprising to me when people say that Trump has hurt the GOP by driving many of its voters away. There are very few Republicans who possess an anti-Trump (or #NeverTrump) identity. And given what Cohen, Barber and Pope tell us about the power of our social identities and group membership, it would be very odd indeed to see a max exodus from the party; more likely is that, as Trump became more popular with the GOP in 2015 and 2016, it became “standard practice” among Republicans to support him.

Well, it always feels good to have one’s priors confirmed, and that’s what I’m sharing with you today: prior-confirming research.

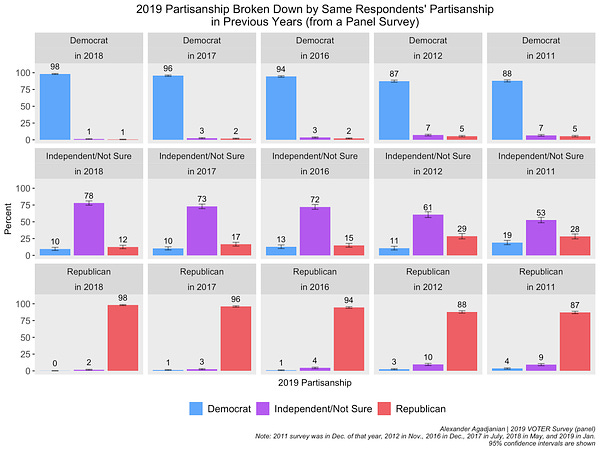

My buddy Alexander Agadjanian crunched some new data from a survey panel—a poll that re-interviews the same people over and over again—and found that the vast, vast majority of people who identified as a Democrat or Republican in 2016 still hold that identity. He tweeted thusly:

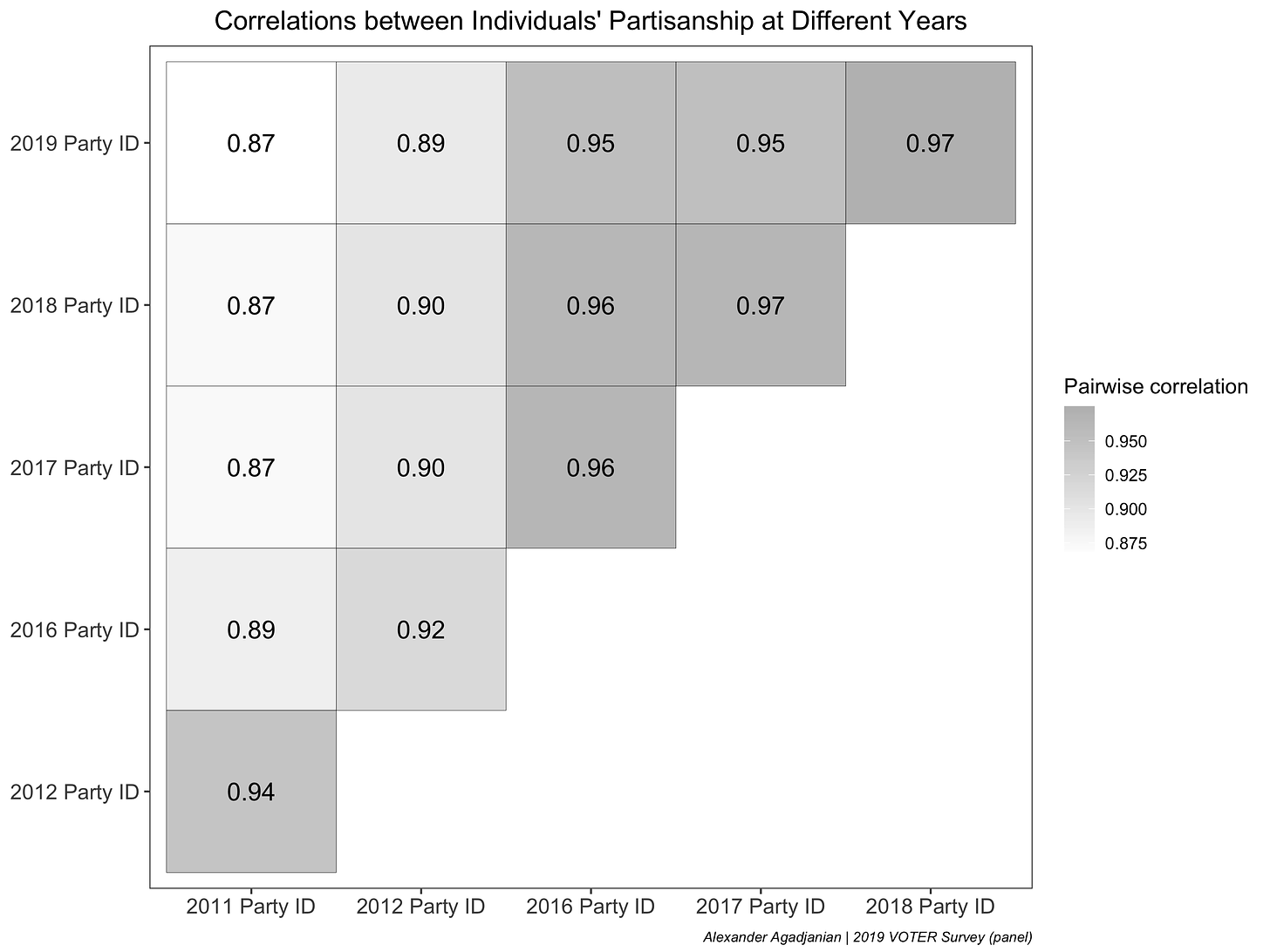

He also shared this graph of the correlation between party identification over different waves of the survey:

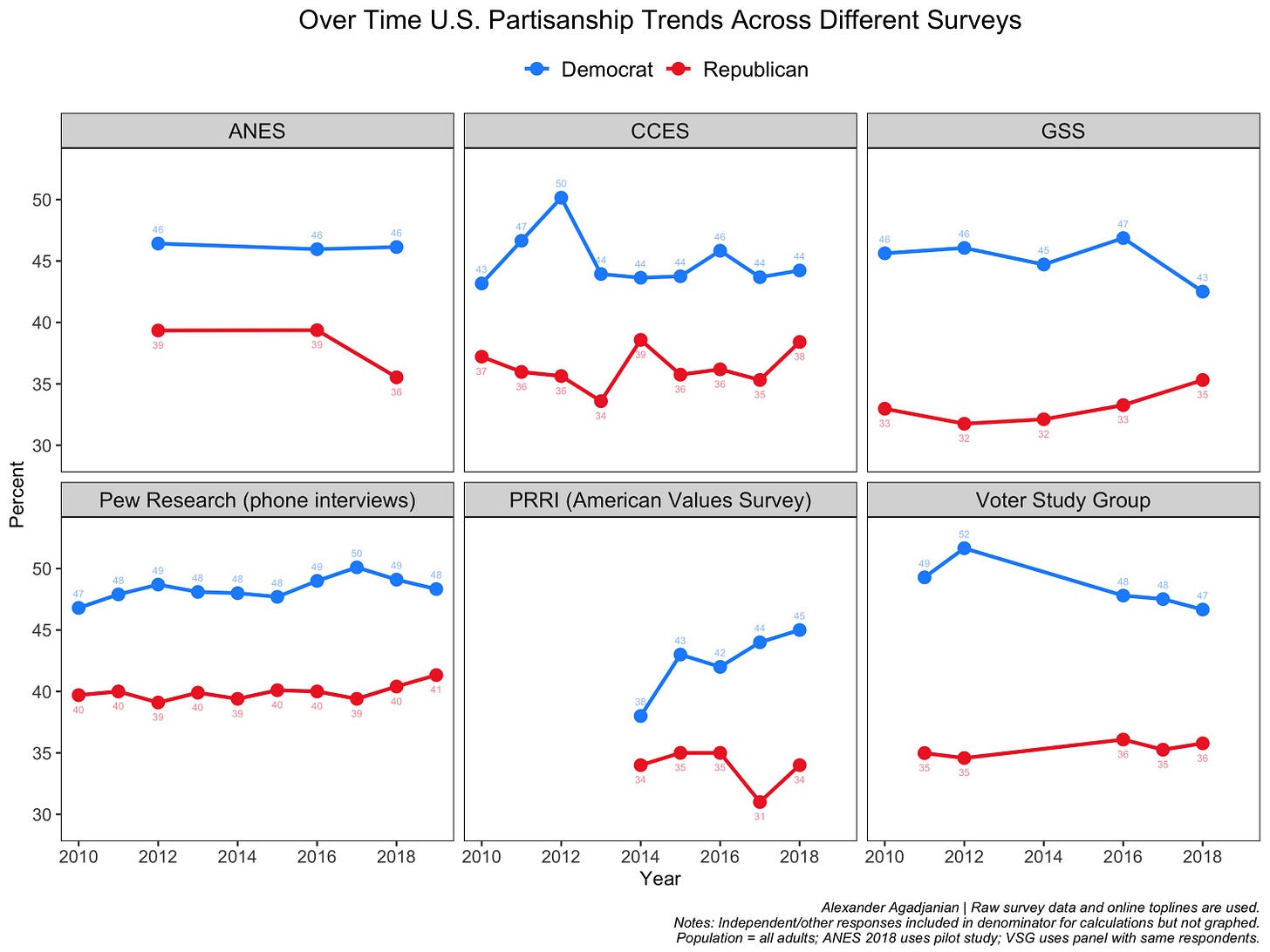

Alexander’s number-crunching revealed that roughly 95% of partisans in 2016 held the same identity in 2019. That obviously goes against the “Trump as a GOP-killer” thesis and with the “partisanship as a strong, dearly-held social identity” one. He also found that aggregate partisanship had held roughly steady over the same time period (a finding that is true across surveys). In fact, if anything we’ve seen an increase in the number of Republicans nationwide over the past four years.

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. These numbers are very relevant to our understanding of Americans as a whole, but there are a couple other factors to consider when gauging how they apply to elections. Namely: turnout.

Non-voters are much more anti-Trump than voters (see the below tweet with survey data), thanks mostly to being much younger than the people who actually turn up to the polls. So while the Republican Party is just as strong (at least on this measure) as it was in 2016, high turnout could send a bunch of New Democrats to the polls come November.

Editor’s note:

Thanks for reading my thoughts on this subject. And thanks for subscribing! Your membership adds up and makes all this newslettering possible (reminder: I do all this work independently). Please consider sharing online or with a friend; the more readers, the merrier!

As always, send me your tips about what you’d like to read about next, or your feedback otherwise. You can reach me via email at elliott@thecrosstab.com or @gelliottmorris on Twitter.

—Elliott

Thanks. None of this is surprising but many in the media should read it. Trump would not have a low 40s approval if he had lost significant GOP support.