Donald Trump did not win in 2016 because the establishment "split the field" | #209 - February 15, 2023

Trump may be in a stronger position for 2024 than popularly believed. (That does not mean he is the automatic winner.)

Nikki Haley, the former governor of South Carolina and Ambassador to the UN under Donald Trump, formally announced Tuesday morning that she will be challenging her old boss for the 2024 Republican nomination for president. That makes for an officially contested primary, with other candidates, including Florida governor Ron DeSantis, likely to join the race in the coming months.

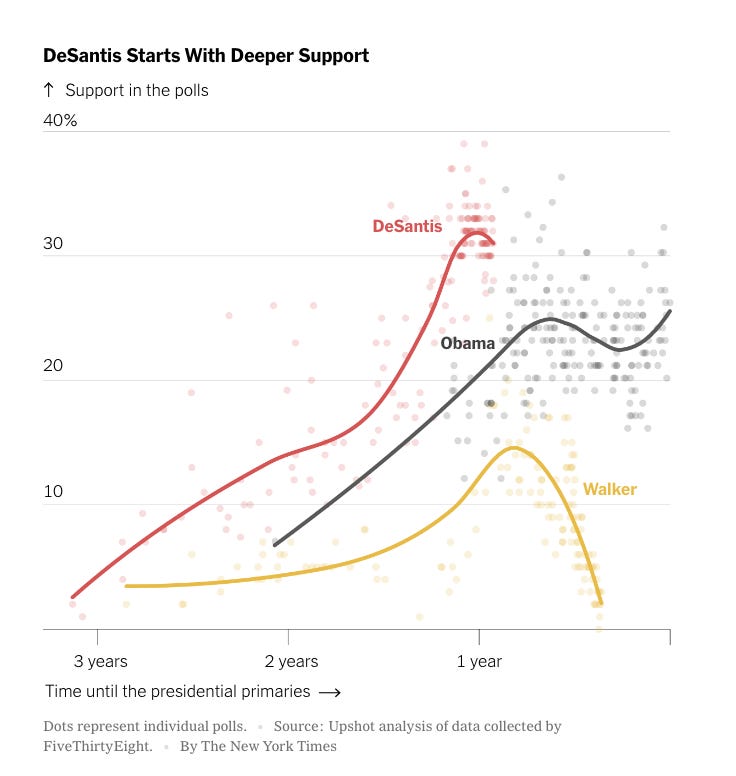

The big question is whether any of them can muster enough support to dethrone the party’s current presumptive leader. The polls indicate DeSantis has a good shot, but survey results right now are unusually noisy. That means they are likely to be even less predictive than usual.

But let’s assume the polls are nevertheless convincing to DeSantis and he jumps into the race. Conventional wisdom about the 2016 primary has analysts stipulating that dividing the anti-Trump vote will allow him to win the primary again with plurality support, as he did last time around. After all, he only won 45% of the popular vote in the primary; surely if Ted Cruz, Marco Rubio and John Kasich had united against him they could have won, right?

Wrong, actually. This cursory analysis of the 2016 primary makes a key mistake. Looking solely at actual primary vote totals obscures how primary voters would have cast their ballots in a two-horse race. For that, you need a survey.

Jonathan Woon, a political scientist at the University of Pittsburgh, and co-authors have an answer for us. In their paper “Trump is not a (Condorcet) loser! Social choice analysis of the 2016 Republican presidential nomination” the authors look at two academic surveys conducted in January 2016. Their goal is to establish whether supporters of Trump’s opponents were in fact opposed to Trump, or if enough would have coalesced around him to push him over the majority threshold in all hypothetical races with only two candidates.

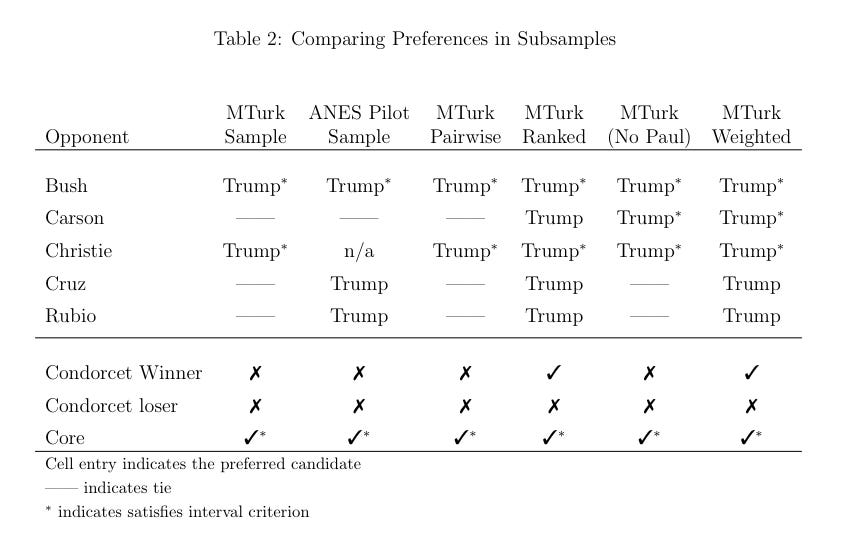

Among respondents who said their first choice in the primary was either Bush, Carson, Cruz or Rubio, more voters support Trump than the total of all other options (so, for Bush supporters, Carson, Cruz, or Rubio). And when respondents were asked to rank the candidates in a simulation of a ranked-choice primary, Trump emerged not only as the winner but a so-called “Condorcet winner”: the person who would win a two-candidate election against each of the other candidates in a plurality vote.

Importantly, in no case was Trump the Condorcet loser, or the candidate that would have lost in a pairwise contest against each opponent. Results in table form here:

There are a number of lessons here. First, the survey reveals the depth of support for Trump as both a first- and 2nd-nth- choice candidate, at least in 2016. It serves as a reminder that taking topline results from polls of the 2024 race may mislead us about the likeliest paths of the primary. The polls today indicate DeSantis has a large base of support — perhaps greater than 40%. But if Trump emerges again as the most popular common denominator among supporters for each candidate, that leaves him a lot of room to secure a majority.

One note here, for what it’s worth, is that Trump is currently polling much better than his head-to-head numbers from 2015. Back then, 41% of GOP primary voters said they would prefer Cruz to Trump in a two-candidate race; 48% said they’d pick Cruz over Trump. Today those numbers are 60% Trump and 30% Cruz. That’s a good reminder that a lot can change in the year before the primary actually begins.

Another lesson, though, is that there are ways for the party to stop Trump if they choose to do so. That’s probably not through candidate selection, but through making the primary process less democratic. Julia Azari and Seth Masket, two political scientists, noted in 2017 that allowing too many candidates to run and people to vote decreased the options available to party leaders to stop Trump (should they have desired to do so). Woon and his co-authors agree that changes to rules on who could run or how delegates were assigned could have made a difference, but caution that it likely would not have been enough:

We agree that party elites with greater control could have nominated another candidate, but the widespread rank-and-file support found in our data suggests that blocking Trump’s nomination would have required shutting him out of Republican primaries and caucuses altogether.

This time, however, support for Trump does look to have waned. For the first time in perhaps seven years, he does not appear to be the obvious presumptive nominee for 2024. He may be the favored candidate, but there is an opening. This analysis of the 2016 primary — which demonstrates his broad base of support translating to majoritarian primary support in an (over-)democratized process — may give some clues as to how to stop him now.

For more on Haley 2024:

Natalie Jackson, National Review: “For Haley, the horse race is just getting started | Measures of a candidate's viability are inherently unreliable this far out. Just look back to the GOP primary race in 2012.”

Nate Cohn, NYT: “What Nikki Haley Can Teach Us About the Republican Party”

David Byler, Washington Post: “Nikki Haley sits in the muddy middle of the GOP polling zone”

Hey Elliott, thank you for sharing - the paper was an interesting read. Since they had the data available, they were able to estimate the core winner based on individual responses*, but I'm wondering what your thoughts are on a more general application to public polls where we maybe just have the toplines.

For example, some polls only ask about the top-two candidates while others ask about a whole bunch of candidates, and that can affect how the top two are scored. On one end of the analysis spectrum, you can consider the poll groups separately, like Nathaniel Rakich did in the linked article. On the other end of the spectrum, you can analyze them as one group but only consider the top candidates, like in Drew Linzer's presidential forecast paper. Both of those feel like it's leaving some information on the table. I've plunked around with mixing the different response scales in a model by estimating the proportion of 'other' voters who would respond with candidate A/B if their first choice isn't on the ballot, but it also feels.... odd (the math checks out but feels like I'm violating some statistical rule).

*edit: this is in reference to the ranked sample, but they found it generally matched up w/the pairwise sample too.

Rakich's FTE article: https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/desantis-is-polling-well-against-trump-as-long-as-no-one-else-runs/

Linzer's paper: https://votamatic.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/Linzer-JASA13.pdf

My (brief) writeup: https://www.thedatadiary.net/posts/2023-01-21-trump-vs-desantis-in-2024-republican-primary-polling/

The model underneath: https://github.com/markjrieke/thedatadiary.net/blob/master/posts/2023-01-21-trump-vs-desantis-in-2024-republican-primary-polling/scripts/primary_poll_model.stan