Critical thoughts on political data journalism 📊 December 6, 2020

Aggressive impartiality creates hollow political coverage, and prediction-first journalism probably reinforces complacency and hobbyism for readers

Thanks as ever for reading my weekly data-driven newsletter on politics, polling and the news. As always, I invite you to drop me a line (or just respond to this email). Please click/tap the ❤️ under the headline if you like what you’re reading; it’s our little trick to sway Substack’s curation algorithm in our favor. If you want more content, I publish subscribers-only posts once or twice a week.

Dear reader,

As someone whose career was steeped in political science, I find the pursuit of prediction for prediction’s sake rather hollow and potentially self-serving. While I think that many of my peers get far too much undeserved flack for things (eg “mispredicting” elections, publishing polls that fall on the wrong side of 0 but are still in the margin of error), I find the criticism that political data journalism writ large distorts our view of politics very valid and increasingly important.

Given recent developments, this seems like a good time to make my case.

…

By way of a late-Thanksgiving, early-Christmas note, I wanted to thank you all for subscribing to my newsletter. I am grateful to have an audience that cares about covering politics through an empirical lens, for many reasons, but a select two follow: First, receiving support for writing is a dramatically underrated boost to confidence and productivity. Hearing from readers after every week’s issue is always reassuring and sometimes even inspiring. Second, and in that vein, having a community of like-minded readers discuss these topics always helps to refine my ideas. It’s a win-win-win, and you all make it possible.

Stay safe, and stay indoors if you can,

—Elliott

Critical thoughts on political data journalism

Aggressive impartiality creates hollow political coverage, and prediction-first journalism probably reinforces complacency and hobbyism for readers

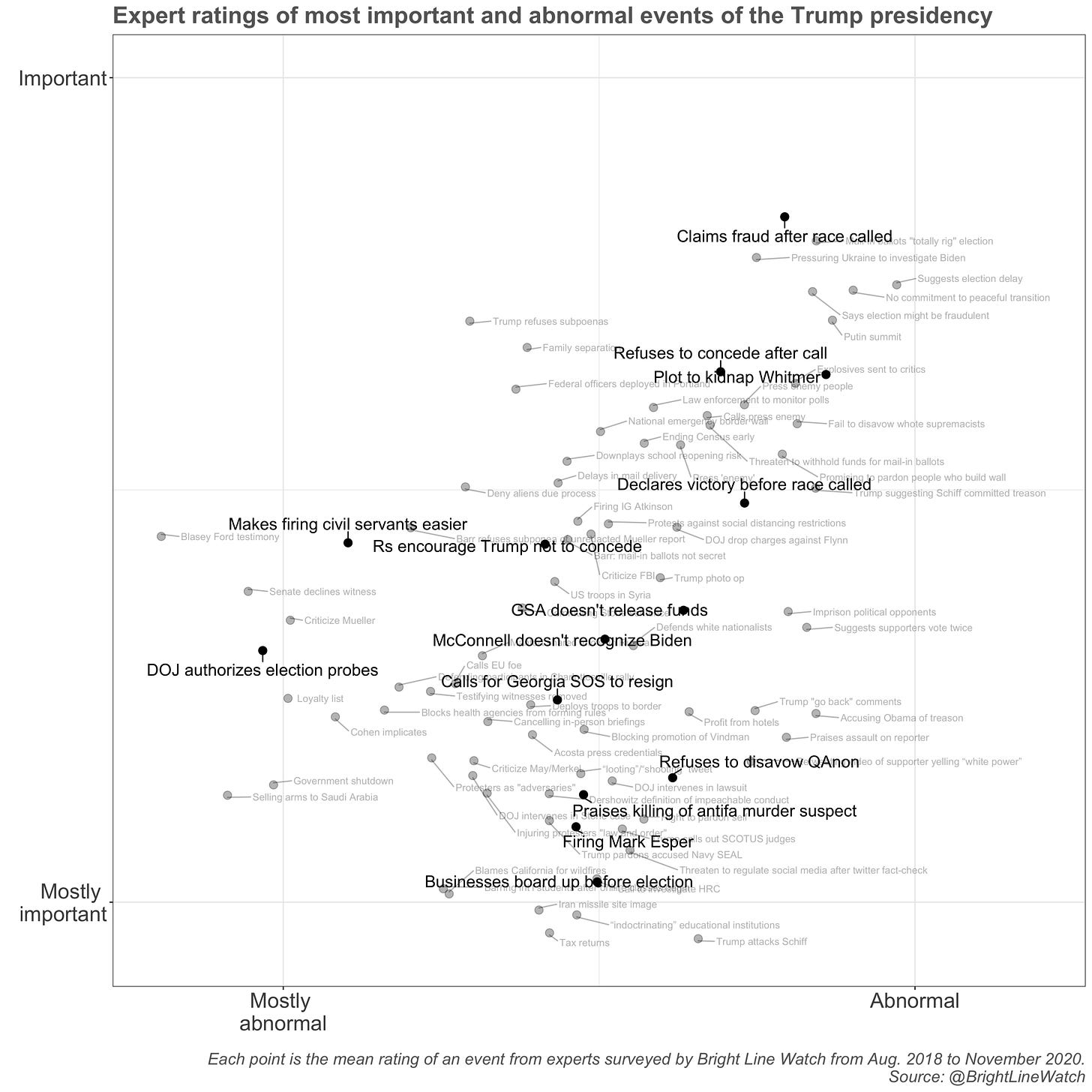

We have lived the last four years in a state of democratic emergency. Of course, it is worth noting that some of us in fact did not live through it; nearly 300,000 Americans have now died from covid-19, and maybe half of them probably didn’t need to.

Both of these statements are a remarkable reminder of the stakes of political action. Who you vote for can seem like an inconsequential action in the moment, but once aggregated, the downstream consequences of collective actions in our political system can be severe.

Yet for all of the norm-breaking, institutions-trampling, democracy-defying and incompetent governing from President Trump and his enablers over the last four years, the last month has proved dramatically more concerning. A Washington Post analysis this week found that just 27 Congressional Republicans would outright acknowledge that Joe Biden has won the presidential election. Some said they might not even accept Biden’s victory after the electoral college certifies him the winner, which is a virtual certainty to occur later this month.

All this comes, mind you, as Trump rallied in Georgia on Saturday, December 6th and urged state lawmakers to overturn the certified results of the election and send Trump’s slate of electors to the meeting of the electoral in two weeks.

We’re in a really bad, precarious place here. The future of democracy is bleak. Most political scientists see a dark future for the state of our union. The problems run so deep that we need a mix of major institutional change (most likely including Constitutional Amendments) and a fundamental redesign of our election information system to dig our way out of this hole.

And yet… political data journalists haven’t really said much on the subject. In fact, faced with this exact scenario on a podcast last month, Nate Silver downplayed the risk of institutional damage and instead ridiculed reporting on the matter in The Atlantic for being too “magaziney.” Obviously, that misses the mark — a very easy and important mark to hit.

I don’t mean to pick only on Nate. My critique is broader. Political data journalists really only have one job. They are hired to cover the latest polls and predict elections. Most of the time, that’s it. (Of course, I would include myself in this criticism, except that I also report on a whole bunch of other data, and have written pretty clearly about the dangers posed to liberal democracy by all of Trump, Republican leadership, and our electoral institutions.)

What political data journalists are not hired to do is cover our politics where, and when, it matters most. For example, as far as I can tell all the recent pieces at FiveThirtyEight about Biden’s transition, Trump’s recent attacks on democracy or even the significance of declining and polarizing trust in our elections in are coming from writers who are listed pretty far down the site’s masthead. And most pieces being written are about Trump’s popularity being low, split-ticket voting being lower than expected (a dubious claim, but a subject for another time), or even what the 2022 elections are going to look like.

This is not an attack on those 538 journalists, to be clear. It’s a commentary about the incentive structures among political data journalists. We have a lot of followers on social media, a lot of information at our disposal. I would reckon that traffic to election forecasts is higher than for any other piece of content in election years. That’s certainly true where I work. But, unlike the 538 bosses, or other prominent data journalists, media pollsters and house forecasters, The Economist has actually covered, in no cushioned language, the dangers that Trump and Trumpism pose to the country.

I worry that all this attention on election modelling, on the horse race, on margins of pre-election polls is distorting our perception of politics. It’s all a game (who’s going to win?) rather than a consequential practice of everyday life (what’s going to happen to my kids if x wins?).

And look, I get it. This makes sense. 538 was funded by the New York Times, ESPN, and now ABC to (a) make money and (b) correct the record when political punditry got circulated. And I think it has succeeded very well on the latter account. But we aren’t really having the conversation about whether political prediction, couched as “data journalism,” is fit for purpose; with that purpose being, chief among all as part of the press, holding political leaders to account. And, to a lesser extent, Nate Silver and his peers/underlings also do not appear fit for purpose in really explaining politics all that well.

I have a few explanations for the lack of content. First is that Nate and his look-alikes in similar outlets/industries (Nate Cohn at NYT, Dave Wasserman for the Cook Political Report, and to a lesser extent Harry Enten at CNN) are employed to talk about the horse race and make money. So, again, maybe this isn’t on them. Maybe they would get in trouble if they talked about how damaging refusing to acknowledge the winner of an election is, or how minoritarian electoral institutions are flawed, or how racism and sexism (in those terms!) are links to support Republicans. If that were true, I wouldn’t say anything on the subject either. Maybe some of them can get a pass on this.

Another likely explanation, however, is a bit more dismaying. Most of the prominent people related to this critique also have a reputation to uphold. If they don’t appear as non-partisan or both-sided as possible, then they might incur some costs that reflect on their work. If Nate Silver says that Trump and the GOP are corrupt, will people stop listening to him when he says the GOP is going to lose an election?

Well... maybe. But it seems like people have decided not to ask a very important follow-up question: who cares? These aggressively impartial data journalists/race handicappers/etc are part of a much larger information system that exists to protect society first, and to forecast elections and aggregate polls second. Of course, we can do both at the same time; which makes the next question all the more devastating. If we are going to pick one, why have so many picked the former?

I imagine that the people on the other side of this argument will be put off by this argument. “My job is to cover the horse race, and that’s it,” I imagine some of them saying. And for the most part, they’re pretty good at it! I have all the respect and admiration in the world for all my peers who are, in my opinion, only victims of broader issues in the news media on this front. But in regards to the ones who own their own news outlets, or who do have more editorial discretion, I would only ask in response: Is that really all we want to use their skill and insight for? And to all the rest of us I want to ask: is this really good for us, or worth our collective time, if it means (for whatever convoluted reasons) that we’re missing out on the other part of the story — the one that, frankly, actually matters?

News outlets don’t actually need to pick between quality horse-race coverage and making normative claims about our politics. Aside from devoting equal resources to the two beats, I also think that the people who are employed to do first can — and should — successfully do the latter. If anything, my position is proof of that.

Posts for subscribers

December 4: Do the problems with election polls doom issue polling too? Reanalyses of 2020 polling data suggest that surveys about political attitudes are probably more accurate than pre-election polls

December 4: This is the worst way to cover the polls. Please stop. Binary reports ("x is up, y is down") are perhaps the worst way to communicate polling information

What I'm Reading and Working On

I have read Francis Fukayama’s The Origins of Political Order before and, after revisiting it this week, I think that some of the genius in writing a history of political development and political philosophy comes with our ability to bring different things to our reading of it each time. Thinking about history’s implications for our political institutions looks a lot different during Trump than in, say, 2011 when Fukayama first published his tome. I would recommend revisiting it if you have it on hand.

Thanks for reading!

Thanks for reading. I’ll be back in your inbox next Sunday. In the meantime, follow me online or reach out via email if you’d like to engage. I’d love to hear from you. If you want more content, I publish subscriber-only posts on Substack 1-3 times each week.

Photo contest

Angus emails and says “Since COVID, Abby Dog has become addicted to squirrel videos.” Hashtag #relatable; my screen time is way up this year.

For next week’s contest, send me a photo of your pet(s) to elliott[AT]gelliottmorris[DOT]com!

Trump pressuring the state legislatures to overturn the election should be a big news story instead of punditry and prediction journalism (both of which I greatly enjoy). The mainstream news generally does not cover this and certainly doesn't analyze the long term implications of this on democracy. There are laws against appointing electors that don't go to the winner of the state's popular vote, so we aren't in a constitutional crisis this election cycle. The state legislatures could change the laws for the next Presidential election, so they don't have to appoint elections based on the winner of the state's popular vote.

I also notice while many supporters of the Electoral College are alarmed about this, they don't want to get rid of the Electoral College. When I suggest, they revisit their position, they shrug. There is a big disconnect there. However when people, myself included, point out that the state legislatures can't overturn the election, they argue that not enough people aren't taking this "seriously".

We have four major problems, the lack of awareness of Trump trying to overturn the results of the election, and the lack of knowledge of the methods he is attempting to do so, the news media not covering these events, and the unwillingness to take the action necessary to prevent this from happening. We potentially are headed towards constitutional crisis in four years.

I think the sentence "And, to a lesser extent, Nate Silver and his peers/underlings also do not appear fit for purpose in really explaining politics all that well." should be extrapolated upon more here. If Nate Silver were still publishing 538 on his own or publishing journal articles I think it would be okay to acknowledge that he only has one job. However, data journalists and the organizations they work for should be faulted for putting out this information for public consumption and not acknowledging that the line between public policy data and policy/politics is nonexistent. Watching Nate Silver offer commentary on politics is painful and uninformative. In my opinion, 538 should have hard-hitting political and policy journalists to put the data into context and flesh out the real-world implications of what is happening.