Welcome! I’m G. Elliott Morris, data journalist for The Economist and blogger of polls, elections, and political science. Happy Sunday! Here’s my weekly email with links to what I’ve been reading and writing that puts the news in context with public opinion polls, political science, other data (some “big,” some small) and looks briefly at the week ahead. Feedback? Drop me a line or just respond to this email.

Dear Reader,

Please forgive my tardiness. As I said in a dispatch on Sunday, I would be sending this letter later than usual.

It is time for a subject near and dear to my heart. Texas: will it go blue? As I wrote in 2018, I believe the chance is less than 50%, but much higher than the conventional wisdom would indicate.

Plus, links to a big map of 2020 donors and the divisions in the Democratic Party.

Thanks for reading my weekly email. Please consider sharing online and/or forwarding to a friend. If you’d like to read more of my writing, I publish subscribers-only content 1-3x a week on this platform. Click the button below to subscribe for $5/month (or $50 annually). You also get the ability to leave comments on posts and join in on private threads, which are fun places for discussion!

My best!

—Elliott

This Week's Big Question

What’s the chance of a blue Texas?

Congressional retirements are a leading indicator for the electoral environment. They suggest that 2020 could be another rewarding election for the Democrats.

Image: Montgomery County Democratic Party

Texas is ground-zero for the Democrats’ potential electoral gains over the next few years. The combination of suburbanites moving left and state population becoming less white is a microcosm of the nationwide changes they benefited from in 2018. And with Trump on the ballot in 2020, it’s likely they experience some of those benefits again.

But what are the odds that Texas actually votes for a Democratic presidential candidate next year?

Any answer is conditional on the candidate that Democratic voters nominate in their primary elections next Spring. If they pick Tom Steyer, for example, I think their odds are worse than if they pick someone like Cory Booker or Joe Biden. To keep things fair, let’s assume that they nominate someone in the 90th percentile of candidates—someone who can effectively campaign in the general election via (a) being popular with the median voter and (b) being able to turn out minority voters.

One big hint at what Texas will look like in 2020 is not found in some national or state-level statistic, but rather in wonky House election news. So far, four of the state’s Republican House representatives have announced that they won’t be seeking another term in office. Among them are Will Hurd, who represents one of the 23 House districts in America that voted for Hillary Clinton and a Republican rep in 2016, and Kenny Marchant, who hails from a seat in suburban Dallas/Fort Worth. Democrats have called the spate of departures the “Texodus”.

Texas’ House delegation could be significantly bluer next time around, not least because these retirements have occurred in swingy districts. This is true especially for Hurd’s TX-23. But not only are they typically competitive already, since open seats more closely match a district’s behavior in presidential years—because the incumbency advantage is not a factor—the picture could look even rosier for Democrats.

These retirements also hint at Texas’s increasing competitiveness in presidential elections. They are a canary in the coal mine. The House environment doesn’t happen in isolation; if representatives foresee a competitive year, presidential candidates should too.

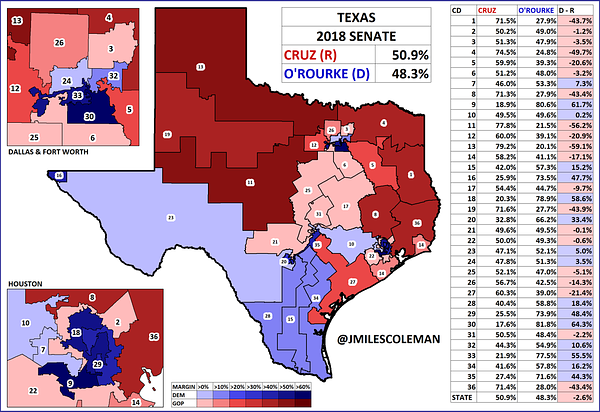

We saw this correlation between office levels at play last year, when Beto O’Rourke nearly kicked Ted Cruz out of his Senate seat. O’Rourke, now running for president, was able to both persuade Republicans to his side and turn out the Democratic base. But perhaps it wasn’t enough; Texas was too crimson-red. Still, O’Rourke carried 16 of 36 congressional districts, including two that went to Trump in 2016, as seen here.

(This might be a reason why Democrats should embrace O’Rourke for their nomination?)

Polling data gives us one glimpse at just how blue—purple, really—Texas might be. One indicator is presidential approval. In Morning Consult’s most recent polling, 51% of Texas adults approved of the president, while 45% disapproved. And since presidential vote choice has become increasingly tied to presidential approval, that could make for a close election next year.

Or at least it would, if all adults voted. But the relevant population is instead likely voters. Because the adult population is much younger and more non-white than the electorate in Texas, these polls of all adults aren’t that helpful unless we correct them. One such correction might be to add the difference between vote intention among 2016 likely voter (LV) and all adults to Trump’s approval rating. This is of course imprecise, but my math for The Economist indicates that voters in the state are about 2-3 points more pro-Trump than are all adults. This gives Trump an implied 53-43 approval rating split and makes him a little more comfortable for re-election: a clear favorite, at least for today. Still, that’d roughly repeat his 2016 margin and be the worst performance for a Republican in decades.

Another indicator is 2020 head-to-heads, but you shouldn’t trust them at this point, so I won’t write about them.

…

Texas might not be a favorable environment for national Democratic candidates just yet. But it’s close. What we may see is a repeat of 2018, a disconnect between the state-wide and House maps. Because Texas congressional districts are really susceptible to swings in suburban areas—thanks to GOP gerrymandering—the Democrats will see multiple House pickups before the state goes blue in a presidential race.

And now, some of the stuff that I read (and wrote) over the last week.

Posts for subscribers:

July 31: The electoral link in support for impeaching Trump. Democrats in safer districts are more likely to support impeachment hearings

Political Data

Thomas B. Edsall (New York Times): “The Democratic Party Is Actually Three Parties“

At the current stage in the contest, according to Khanna, very liberal Democrats are the most engaged and play a disproportionate role in setting the political agenda.

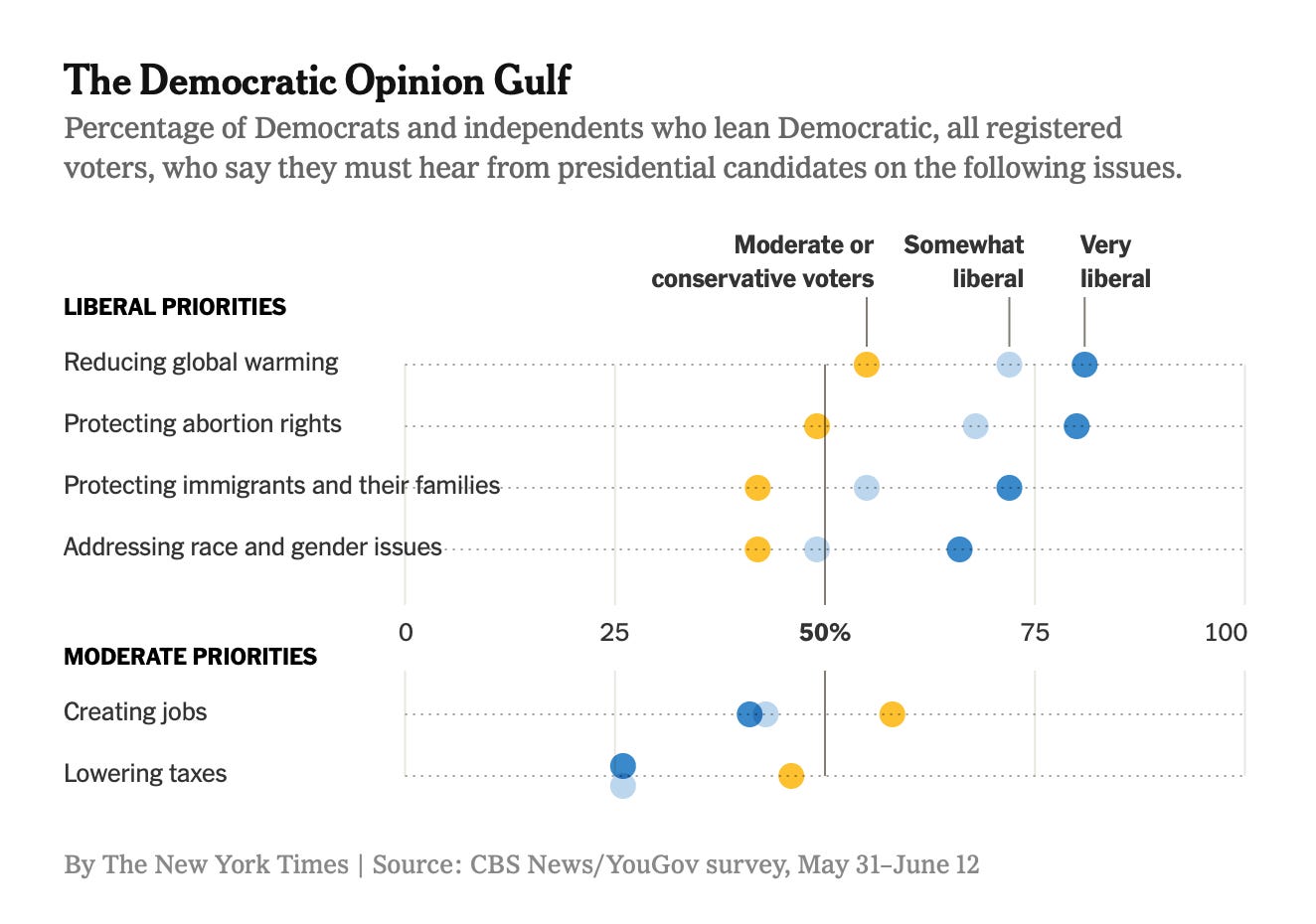

The three ideological groups favor different sets of policies. On the left, the very liberal voters stress “the environment, protecting immigrants, abortion, and race/gender,” Khanna emailed me, while the moderate to conservative Democrats are “more concerned with job creation and lowering taxes.”

The accompanying chart, which shows what Democrats in the early primary states want candidates to talk about, illustrates these differences.

While 72 percent of very liberal Democrats want candidates to protect immigrants, 42 percent of moderate-to-conservative Democrats share that priority. Sixty-six percent of the very liberal groups want candidates to address “race and gender issues,” compared with 42 percent of the moderates.

Even more interesting is the way these three categories of Democrats split on some of the most contentious issues raised over the first two nights of the Democratic debates: providing health insurance to undocumented immigrants and a Medicare-for-all proposal that would eliminate private health plans.

Also from Edsall: “The Heartland Is Moving in Different Directions”

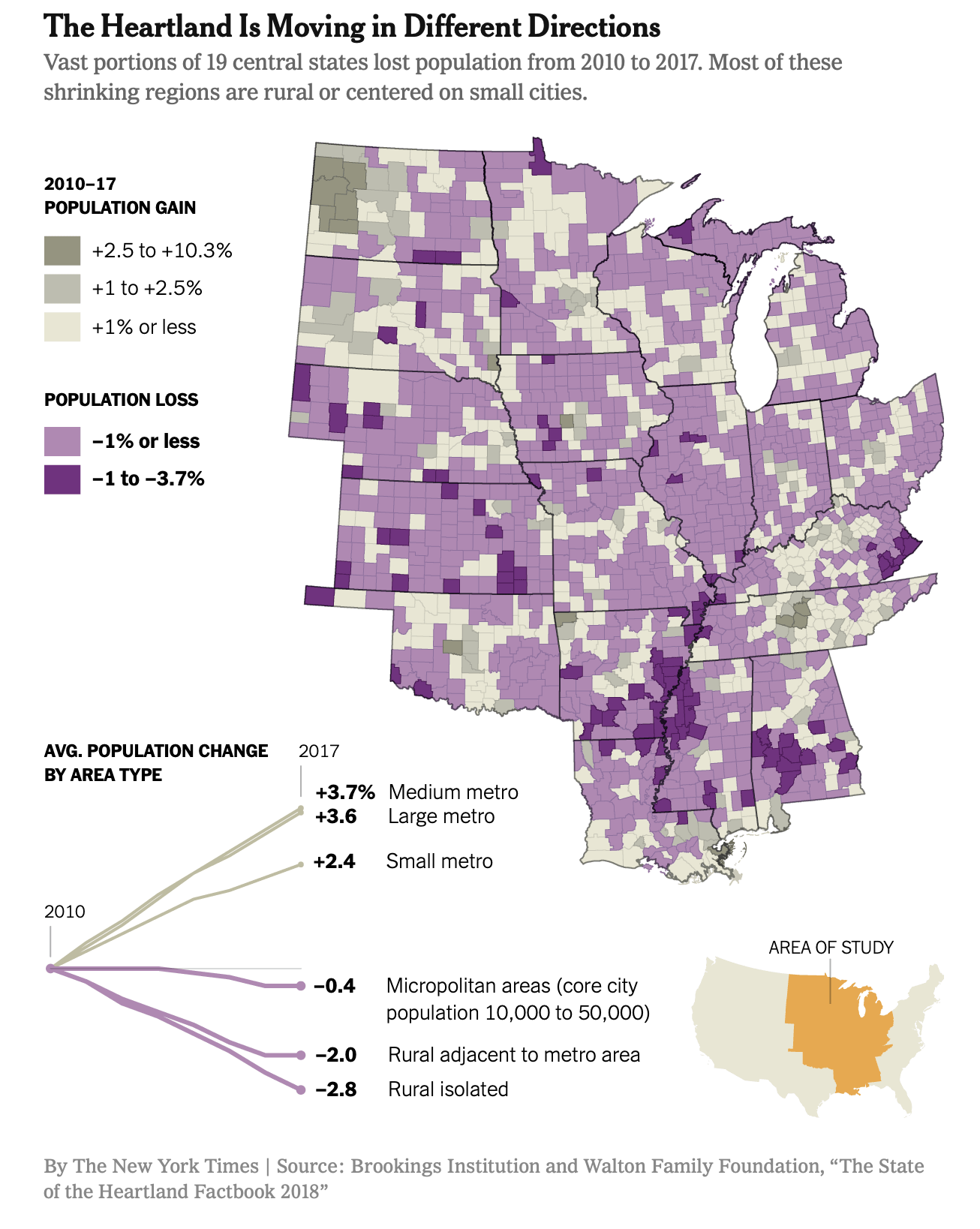

The growing share of the Midwest population living in “larger, denser areas through much of this decade has likely reinforced the voting tendencies of younger, more diverse voters, in ways that may help Democrats,” Muro wrote by email.

In statewide contests, which of course are where the presidential competition for Electoral College votes is fought, the trend toward urbanization could help the Democratic nominee. Muro notes that

While only some Midwestern bigger metros are true stars, in state after state the larger metros — while not attracting large numbers of new residents from outside their states — are drawing in migrants from the surrounding cities and towns within the state. These migrants are often the young looking for education or jobs; they are leaving smaller towns and smaller cities behind, including their elders.

The result is a population-sorting dynamic in the Midwest that parallels national trends, albeit in weaker fashion. Muro observes that

The larger, more vibrant Midwestern cities grow a little, but it’s somewhat at the expense of the left-behind residents of the rest of the state. So the more successful Midwestern hubs — Columbus, Kansas City, Des Moines, Madison, Minneapolis-St. Paul — are pulling away from the rest of their states, just as are Boston and San Francisco and Seattle from the rest of the nation.

In fact, the growing urbanization of the Midwest, combined with the decline of pro-Republican rural communities, as shown in the accompanying graphic, may improve the odds for the Democratic Party and its candidates.

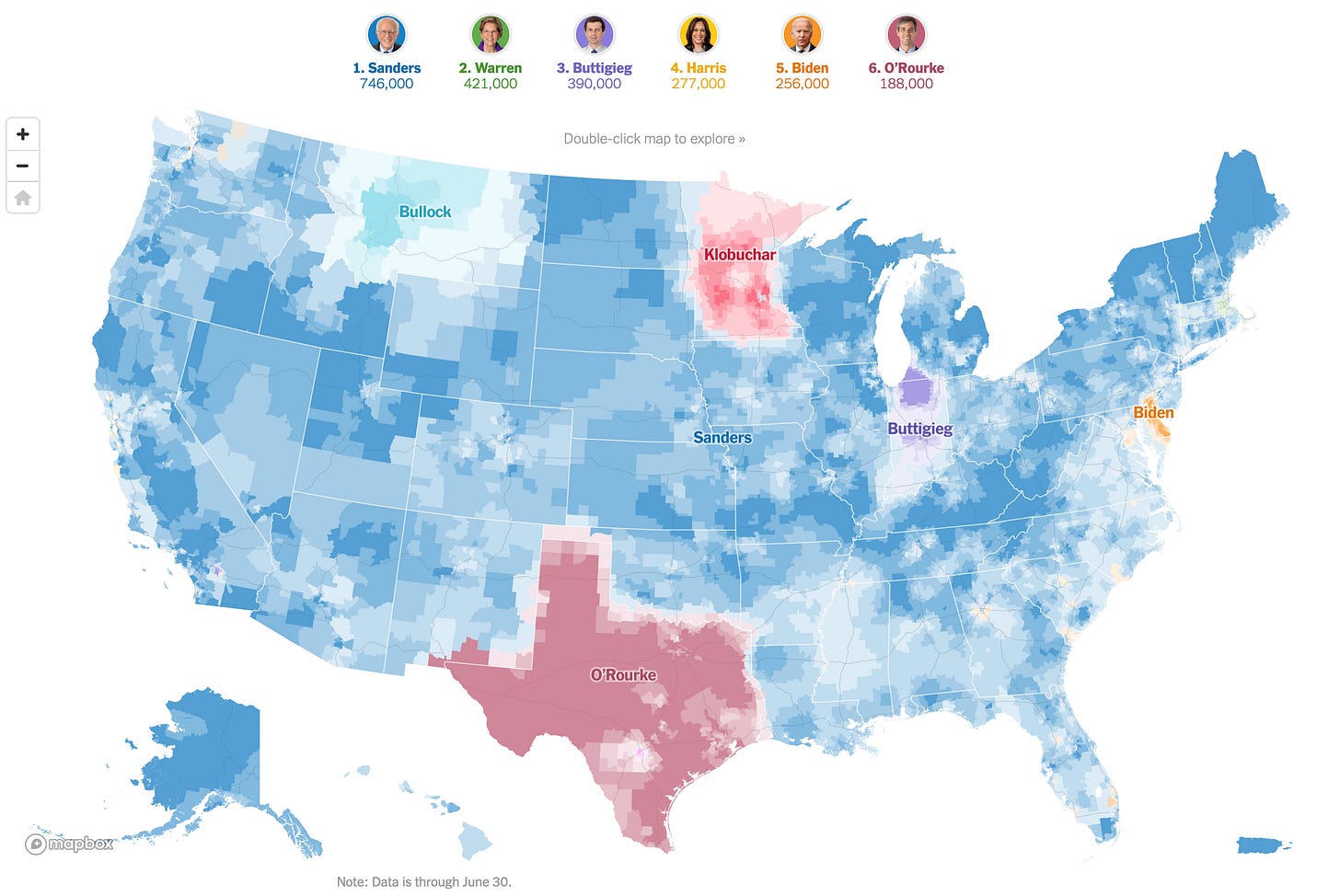

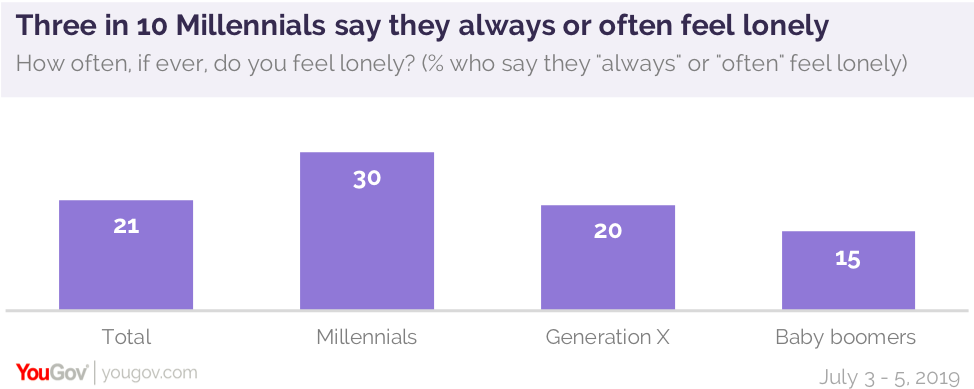

Josh Katz, K.K. Rebecca Lai, Rachel Shorey and Thomas Kaplan (New York Times): “Detailed Maps of the Donors Powering the 2020 Democratic Campaigns”

Other Data and Cool Stuff:

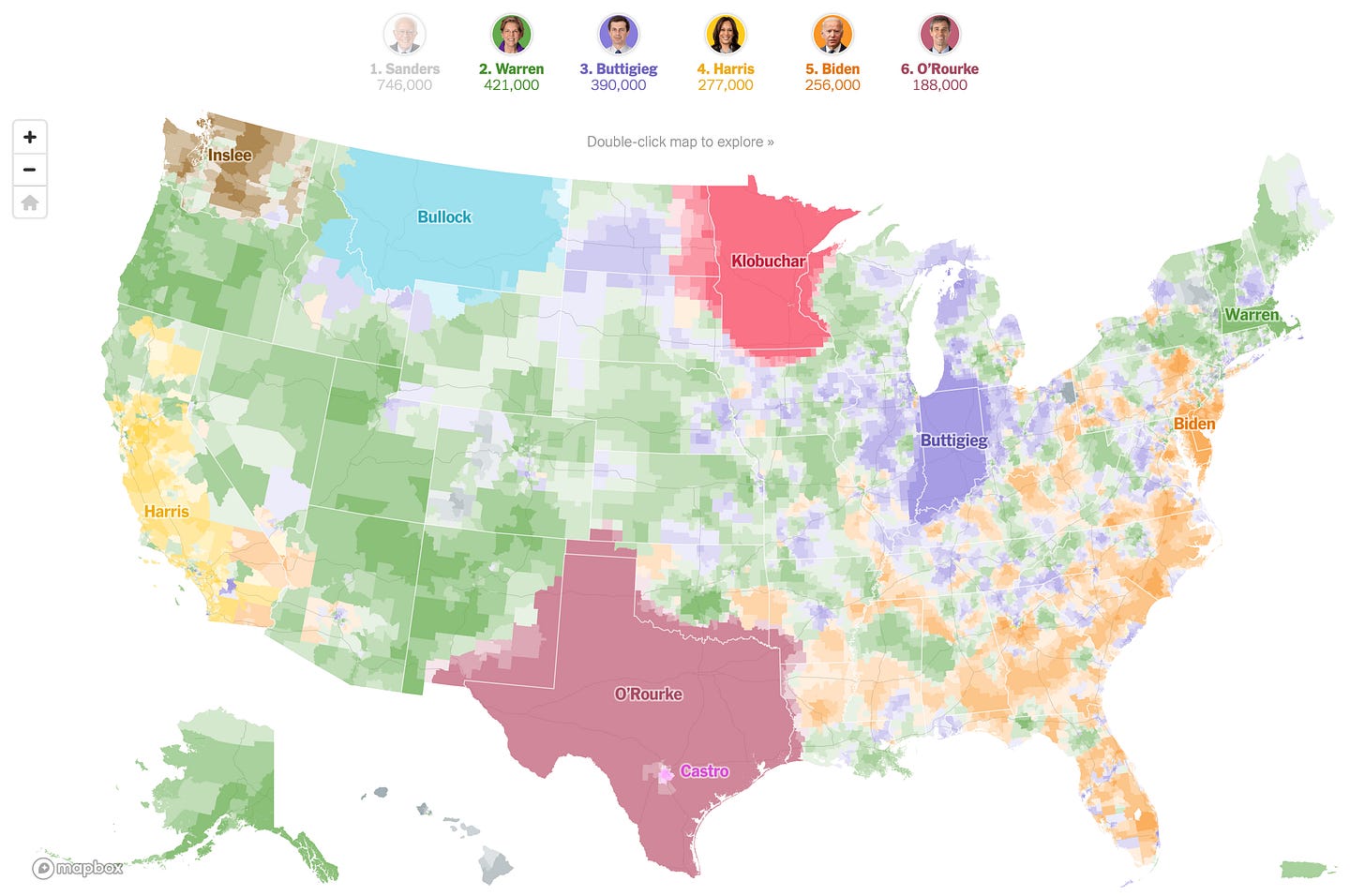

Brian Resnick (Vox): “22 percent of millennials say they have ‘no friends’”

Today, members of the millennial generation are ages 23 to 38. These ought to be prime years of careers taking off and starting families, before joints really begin to ache. Yet as a recent poll and some corresponding research indicate, there’s something missing for many in this generation: companionship.

A recent poll from YouGov, a polling firm and market research company, found that 30 percent of millennials say they feel lonely. This is the highest percentage of all the generations surveyed.

Furthermore, 22 percent of millennials in the poll said they had zero friends. Twenty-seven percent said they had “no close friends,” 30 percent said they have “no best friends,” and 25 percent said they have no acquaintances. (I wonder if the poll respondents have differing thoughts on what “acquaintance” means; I take it to mean “people you interact with now and then.”)

In comparison, just 16 percent of Gen Xers and 9 percent of baby boomers say they have no friends.

Political Science, Survey Research, and Other Nerdy Things

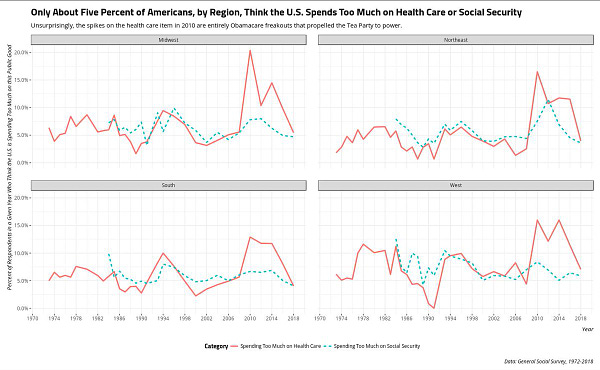

Steven Miller: Actually, Midwestern voters like free stuff, too

What I'm Reading and Working On

I’ve been fascinated by The Lord of The Rings recently. I know that’s off-brand, but hey, it’s (apparently?) a very good book! Look out for my work on drug prices, gun control and the primary.

Something Fun

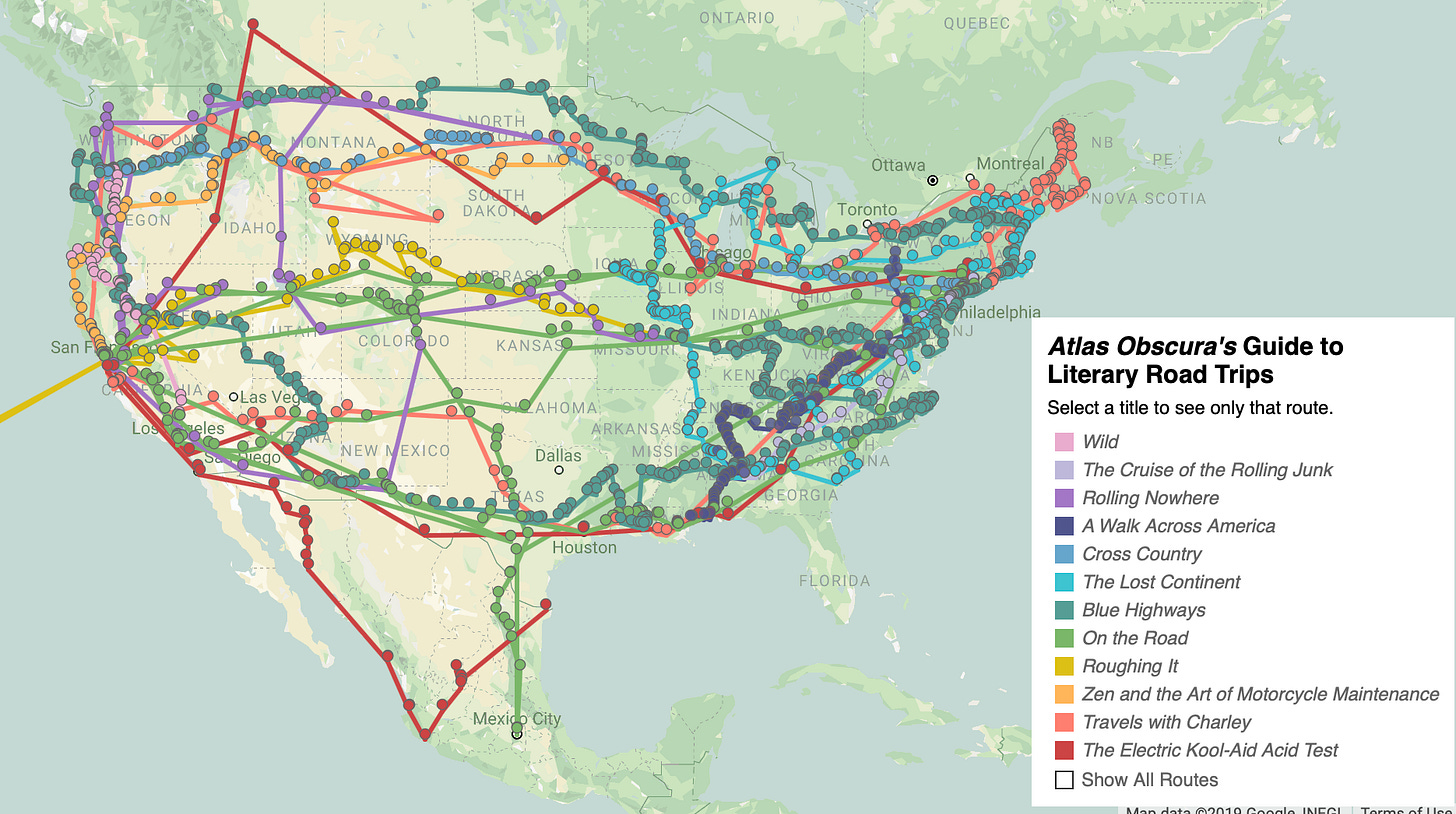

I enjoyed this map of literary road trips from the folks at Atlas Obscura:

Thanks for reading!

Thanks for reading. I’ll be back in your inbox next Sunday. In the meantime, follow me online or reach out via email. I’d love to hear from you!

If you want more content from me, I publish subscribers-only posts on Substack 1-3 times each week. Sign up today for $5/month (or $50/year) by clicking on the following button. Even if you don't want the extra posts, the funds go toward supporting the time spent writing this free, weekly letter. Your support makes this all possible!